Largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides, are native to the eastern half of the United States, southern Quebec and Ontario, as well as northeastern Mexico. They are also known as bucketmouths, widemouths, bigmouths, green bass, and the widely used “black bass” that was popularized in Dr. James A. Henshall’s classic Book of the Black Bass. Their habitat range now includes the entire lower 48 states and other parts of Canada and Mexico, and they have become one of the most widely introduced freshwater fish in the world, in part due to the fact that they tolerate extremes of cold and warm water, fight doggedly, take artificial lures, including flies, reproduce well, and put on prodigious weight if given a chance.

They are intelligent fish and can be extremely difficult to catch, due to their ability to remember things for as long as a year, mostly bad things, such as sharp objects in their mouth and boat and motor noise. (See “Can Fish Think?,” California Fly Fisher, September/October 2016.) The conventional and highly successful angling technique of drop shotting, with a weight below a lure or bait, jigged near the bottom, evolved in Japanese lakes, where bass can be very finicky and challenging, perhaps even more so than here in the United States.

Thirty million bass anglers in the United States spend 60 billion dollars annually pursuing their quarry. Forty-three percent of freshwater anglers fish for bass, 30 percent for trout, and 28 percent for crappies. Fly-rod angling for bass increases every year. It is popular in the East, South, and Midwest, and more and more California fly-rod anglers are discovering it as a new activity for waters in their own backyards, whether these waters are ponds, slow-moving streams, natural lakes, or immense reservoirs situated from San Diego to Oregon and from the Pacific Coast to the Great Basin.

Largemouths, both the northern-strain largemouth, Micropterus salmoides salmoides, and the southern, Florida-strain fish, Micropterus salmoides floridanus, are aptly named. Their jaw angle extends beyond a vertical line drawn down from their eyes. This is not true for other closely related and smaller bass, including the shoal bass, Micropterus cataractae, the spotted bass, Micropterus punctulatus, the red-eyed bass, Micropterus coosae, the Guadeloupe bass in Texas, Micropterus treculi, and the Suwannee bass, Micropterus noticus, which all have shorter, smaller mouths.

To say that these bass have smaller mouths is somewhat misleading, though, because all Micropterus species are voracious and will eat anything that they can get into their gut, including frogs, snakes, birds, crawfish, water newts, leeches, salamanders, and other fish. As juveniles, they readily eat midges, damself lies, dragonflies, mayfly nymphs, and caddis pupae. Mature fish will eat the huge Hexagenia nymphs and emerging adults with abandon. The really big boys feed on planted rainbow trout. It’s said that both largemouths and striped bass can “remember” the day that hatchery trucks will arrive and key in on planted rainbows. They may also key in on truck aerator vibrations from long distances. Several monsters have been taken from Castaic Lake in Southern California. California Department of Fish and Wildlife records show that of the 25 largest bass caught in the United States, 21 were from California, thanks to the CDFW’s hatchery trout programs. Economists talk of “wealth redistribution.” This policy is protein redistribution.

In California, the Alabama or Kentucky spotted bass, Micropterus punctulatus, is adapting well to steep-sided reservoirs such as Shasta, Orville, Don Pedro, Englebright, Rollins, and others, feeding on forage fish, including threadfin shad, (Dorosoma petenense) pond smelt (Hypomesus olidus), stocked rainbow trout, and kokanee salmon. The world record for these bass is 11 pounds, 4 ounces, and their numbers and range are growing. The spotted bass is distinguished by the fact that it has fused spiny and soft dorsal fins. This species will suspend more readily over deeper water than largemouth bass and is producing world records in New Bullards Bar Reservoir near my home because of the presence of ample supplies of protein in the form of stocked trout and kokanees.

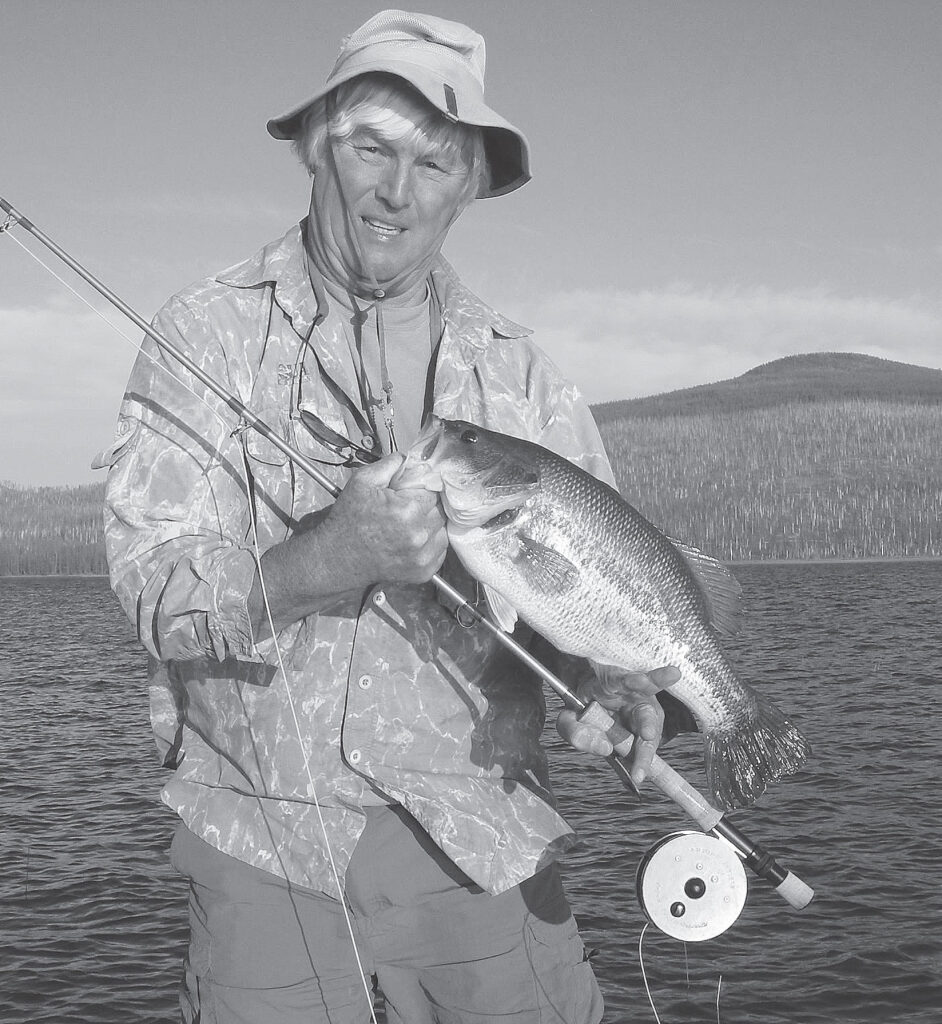

Fly fishers, however, are more likely to be familiar with the northern and Florida largemouth strains, which tolerate warmer water. The Florida strain has 69 to 73 scales along the lateral line. The northern largemouth has 59 to 65. The world record for the Florida largemouth came out of Montgomery Lake, Georgia, in 1932. It weighed 22 pounds, 4 ounces. Larger specimens are reported, but not authenticated and recognized, one coming from a reservoir in Japan and another from a small urban lake near Santa Rosa, California.

William A. Dill and Almo J. Cordone have combed the often confusing records and in History and Status of Introduced Fishes in California, 1871–1996 join others in speculating that when smallmouth bass were introduced in California in 1874, largemouths may have been mixed in with the original plants in Crystal Springs Reservoir on the San Francisco Peninsula, the Napa River, and Alameda Creek in the East Bay. Other, possibly inaccurate records show largemouths having been stocked in California in 1891, their origin being Quincy, Illinois, and their final destination Lake Cuyamaca in San Diego County and the Feather River near Gridley. Additional reports suggest plantings in Clear Lake in 1888 and again 1896. Fish were originally transported in railroad-engine water tenders and later in aquarium cars after the completion of the transcontinental railroad in May 1869. Different lots of fish often were combined for transport, and records were not up to modern scientific standards.

Paperwork relating to the specific introduction of Florida-strain largemouths is more accurate. The first shipment, from the Holt State Fish Hatchery near Pensacola, Florida, in 1959, went into Upper Otay Reservoir. Another shipment went into Clear Lake in 1969 and subsequently into other appropriate waters. My research doesn’t indicate if they were planted directly in the California Delta, but if not, it is logical to suggest that they migrated down west-slope Sierra rivers from known stocking sites such as Lake Amador, which drains into the Mokelumne River. As with smallmouths, there was a commercial fishery for a while in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta and in northern rivers. Northern largemouths grow faster in their first year, but are quickly passed by the Florida-strain fish in subsequent years. The two strains also hybridize. A friend who is a tournament bass fisherman says that the Florida and northern strains are similar in their sensitivity to barometric changes. A funk follows a dropping barometer after a front has passed. Often the leading edge of a storm produces a ravenous bite. But years of fishing have shown that Florida-strain fish will take top-water baits more readily than the northern largemouths. My top five fly-rod bass were Florida-strain fish, and three came to top-water bass bugs. I have traveled to fish exotic locations on the west slope of the Mexican mainland with bass bugs because the fish there are Florida-strain monsters and take surface flies. It is interesting to note that largemouths of either strain grow much faster on a diet of threadfin shad and pond smelt than on bluegills and other sunfishes. All their forage fish, other than rainbow trout and the Sacramento perch, Archoplites interruptus, are introduced species in California. The signal crawfish, another introduced species in our state, has lower food value due to the indigestibility of their shells, though volume can make up the calorie difference, and bass seem to really like them.

Largemouths are often alpha predators in their environment, but not always. In the East and northern Midwest and into Canada, pike and muskellunge prey readily on bass of all species. Otters are voracious predators. In the Delta, sea lions take their toll. In the Sacramento– San Joaquin system, Sacramento pikeminnows, Ptychocheilus grandis, a native species, keep bass numbers in check.

In spite of predators, largemouth bass proliferate because a single mature female may produce and deposit two thousand to forty thousand eggs in a shallow-water nest scooped out of gravel or sandy mud in shoreline areas when spring water temperatures reach 58 to 62 degrees, though the temperature preferred for spawning may differ in microenvironments. Fish in California move inshore as early as January or February. Much is determined by latitude, altitude, day length, wind, and fluctuations in winter temperatures.

Fry grow maximally in 81-to-86-degree water. The fry hatch in five to ten days, depending on water temperatures. Higher temperatures result in faster hatching, and the young fry that reabsorb their yolk sacs are under the watch of a male nest guardian.

Life expectancy of the fry is measured in days — predators include sunfishes, herons, egrets, kingfishers, crawfish, newts, and many other aquatic and terrestrial creatures, including predatory dragonfly nymphs. Other morbidity factors include reservoir draw-downs after eggs have been deposited. Large, more mature fry are preyed on by female bass, and there can be a “fry” bite later in the cycle. Only 5 to 10 fry from a single nest might live to reach a length of 10 inches. The life span of the largemouth bass that survive is on average 16 years, with a range of 15 to 23 years. Size varies with environment. One Florida-strain 10-pound bass ear otolith sample suggested an age of just four years. But a 3-1/2-pound northern largemouth from Montana was pegged at being 19 years old. Fish of an inch to 8 inches long are usually a year old, and fish of 9 to 10 inches in northern latitudes are 2 years of age if conditions for growth are good.

Regardless of when and where originally planted, these fish prefer slow-moving and still waters. Largemouth in California bunch up and spend winter months in deep water havens. As days lengthen and water temperatures rise, along with more available sunlight from a lessening of cloud cover, these fish “stage” at intermediate depths. This may occur on shelves, ledges, and even submerged roadways. At that time, they start feeding more aggressively, and their strike zone increases. Then they move inshore, often following small channels or ridges to shallow water in prespawn mode, when fish begin to feed actively and start looking for partners. Females search for nest sites, often returning to the same areas year after year. Large females arrive early, and because of their size and aggression, they get the best nesting spots.

These patterns are influenced greatly by incoming fronts associated with storms. Fish may move in and then out, go off the bite and back on, before locking in on the spawn, which often comes on a full moon. But not all fish are in the same part of the spawning pattern at the same time. This is a survival trait that has evolved over millennia. If every mature fish spawned at the same time, nests could all be wiped out in a lowering of water levels, whether natural, as in a lake, or in a reservoir with large spring drawdown for irrigation or flood control.

Females dig the nest with their fins and tail, pair with a smaller male, deposit eggs, which are quickly fertilized, and initially guard and defend the eggs from all sorts of predators. For a while, bedding females will refuse any angler’s offering that isn’t right on their nose or that doesn’t suit their peculiar fancy. When the fry hatch, males guard the nest for a while, then adult fish abandon the nest site, but remain inshore and go on the feed, often with abandon. All phases are good times to take bass on a fly rod.

Top-water flies are most likely to produce in the latter phases.

Some anglers frown on disturbing bedding fish. If you catch these fish, handle them with care, as you should all bass. I see anglers practicing catch and release, but are still very rough on the fish. More care, especially in tournaments, where multiple treble, barbed hooks and heavy-handed handling are the norm, needs to be preached.

If you haven’t joined the increasing ranks of fly-rod anglers who have discovered this exciting game fish, this spring offers the opportunity to expand your horizons. If you think that a rainbow sipping a dry fly is thrilling, you won’t believe what it’s like when a bass blows up on a popper.

Largemouth Tips and Tricks

Near my Sierra Foothills home at the 1,200-foot elevation level, I get into top-water action by April. Higher up, at Scott’s Flat Reservoir at 3,071 feet, surface action comes a bit later. Look for carpenter ant falls. In Sierra impoundments such as Antelope, Prosser, Stampede, and Almanor, it starts in June or July, depending on runoff and water temperatures. Don’t be afraid to toss a few floating bugs before then, especially after several days of warming temperatures.

In lakes with forage fish such as pond smelt and threadfin shad, bass often drive the bait against bank indentations or into small coves. Sometimes this also occurs in a larger cove or even in open water, where the bait will “ball” up as a protective mechanism. If bait balls are being busted, remember that the bigger fish will be below, waiting for dead sinkers or injured minnows. Cast a chartreuse-and-white Clouser or Gummy Minnow and let it fall and tumble for a while, even when bait is driven up tight to the shore by smaller fish. Let that fly sink, and you will hook up on larger fish.

Another trick learned from friends who fish San Luis Reservoir and O’Neill Forebay is to cast a Crease Fly on a shortened leader with an integrated sink-tip shooting line (4 inches per second or faster). Count it down, and then start retrieving with several short strips mixed in with pauses, followed by longer ones. The buoyant Crease Fly will rise and flutter. That’s when the strikes come, often from fish that will refuse other approaches. This works on stripers, too. In Mexican fisheries, Picachos and El Salto, sheer numbers have taught us that a slope-faced Crease Fly work much better than the flat-faced one . . . they hop around and have overall better action.

My annual trip to Mexico this past January reinforced the observation that dark top-water flies work well early and late in the day. We also found once again that bass aren’t randomly distributed. A given cove or inlet may hold fish, while another section of water that looks similar to you, but perhaps not to the fish, won’t. One side of a body of water will have bass, the other will be void of them. Different structure will be preferred on different days at different times. However, one constant is that bass love shade.

Among fly-rod bass anglers, “Float-n-Fly,” a technique using Balance Minnow patterns under indicators with long leaders, is catching on. (See “The Balance Leech,” by Denis Ibister, California Fly Fisher, March/April 2015 ). This is an extension of the “popper-and-dropper” technique. It allows a subtle and slow approach in the winter and early spring and again later as fish become more wary after being fished over repeated times and exposed to boat traffic. Work inshore areas starting in February or even earlier, if it is a mild winter.

A mainstay fly throughout the early phases of the spawn is my improved Calcasieu Pig Boat on a 10-foot or 11-foot leader and floating line. The fly is nothing more than a weighted body with palmered crawdad-color UV Polar Chenille and a 12-strand silicone Sili Leg hackle. I tie them on Daiichi 2720 hooks in the 3/0 and 5/0 sizes. Add a trailer for more action. It can be fished “on the fall” and slower than traditional streamers. I work steeper banks and structure, such as dock pilings and rocky areas, easing the fly down steps and ledges.

Fish slowly, thoroughly, and carefully, but if nothing happens after a while, move on and change tactics. Don’t be afraid to tell your guide or your brain; “Another place, another fly, another tactic.”

And next year, extend your largemouth season and start fishing earlier. Bass move inshore much sooner than many think, but their metabolisms aren’t yet up to speed, so fish extra slowly with subsurface patterns.

— Trent Robert Pridemore