In California, we fish all winter, because we can. Angling during winter in the Golden State might mean ice in the guides one day, followed by a second application of sunscreen a day or two later. Fishing for steelhead on the upper Klamath River in the winter can provide both extremes and almost everything in between.

The upper Klamath lies in a banana belt north of the Shasta Valley, in a rain shadow south of the Siskiyou Pass and west of the Trinity and Marble Mountains. The river is also a tailwater, with regulated releases below Iron Gate Dam, which help keep the angling consistently good through all but the most severe storms. Miles of marshland, which make up the headwaters, also provide relatively warm water temperatures and absorb precipitation like a sponge, making the Klamath one of the last rivers in the state to blow out and one of the first to drop, clear, and provide quality angling in days, rather than weeks after major storms.

So . . . why haven’t you visited?

Most likely because the Klamath is a remote river, nearly a full gas tank away from the larger population centers of California. It is located just south of the Oregon border, in Siskiyou County, which is approximately the size of Connecticut, but with a population of only about forty thousand people. The county is the home of several other fine trout and steelhead rivers and one of the few places left in the state where the trout and steelhead vastly outnumber the human population.

When to Visit

Since the Klamath can fish well almost anytime in the winter, the old adage “The best time to fish is when you can” is not far from the truth. The first runs of steelhead begin showing in the upper river below Iron Gate Dam in October and continue arriving well into January, providing angling opportunities all winter, until the steelhead spawn in April and May. The Klamath’s fall and winter steelhead runs also overlap (unlike those on the Rogue and Trinity), without a slow period of fishing in between the runs.

There are some differences in the fish and the fishing that, depending on your appetite, might guide you in planning a trip to suit your preferences. Late in the fall and early in the winter is the time of year when the catch rate is highest. Water temperatures are typically in the 50s and upper 40s, the fish are actively on the grab, and it is not an uncommon occurrence to hook a fish on each pass through a run. This time of year, there are still a few chinook salmon spawning, and it can be easy to locate the steelhead stacked just downstream from them. With nearly perfect water temperatures, it can also be an ideal time to swing flies successfully.

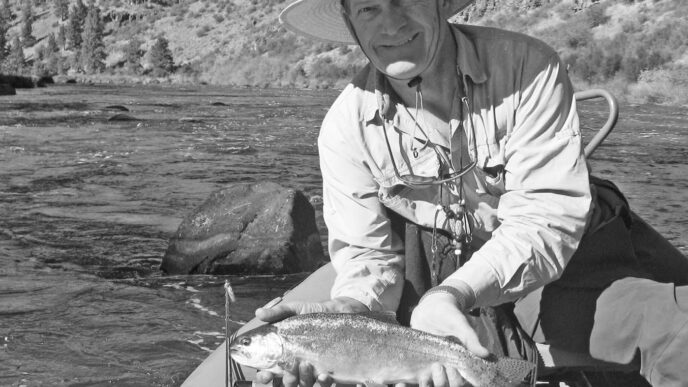

So what is the downside? Nearly all the fish you will find at this time of year will be small. The run is made up primarily of “half-pounders,” trout-sized juvenile fish that earlier in the spring traveled downstream to the salt and returned in the fall. They are accompanied by a run of adult steelhead that came upstream the season before as half-pounders, returned to the salt, and are arriving once again, this time to spawn. The half-pounders are 10 to 16 inches long, while the early run adult fish are typically wild and 16 to 23 inches or so. The adult steelhead have typically spent just half a season in the salt as half-pounders, followed by another full year in the salt, which makes them small, compared with adult steelhead in other rivers, which spend two years or more in the salt. A steelhead 25 inches or longer caught in the early season on the Klamath is considered exceptional. All wild fish, by the way, must be released.

Sometime in December, winter sets in for real. Water temperatures drop into the lower 40s, with air temperatures on most mornings below freezing. The fish become lethargic in the cold, and the grab softens as a result. Fish no longer chase down swung flies with reckless abandon, the salmon have spawned and are gone, and the fishing can become very challenging. Fortunately, this is also the time when the fall run of hatchery fish arrives in the upper river, along with a run of bigger wild fish. These fish are typically 21 to 26 or 27 inches long and heavy bodied, with an occasional exceptional fish that can be even larger.

While the opportunity to catch these bigger fish is to be enjoyed, these new arrivals usually also spark the bite for steelhead that have been in the river for a while. It is important to remember that steelhead do not travel hundreds of miles to eat, not even to eat the flies that you painstakingly tied. They come to spawn, and their behavior reflects this primal urge. I liken this phenomenon to a bar scene. Imagine a pub where the patrons have been sitting, nursing their drinks, and listening to music or watching television when a whole sorority suddenly arrives. Everyone in the place livens up, with not only the new arrivals ready to party, but almost everyone buying drinks and looking to dance.

Winter-run fish arrive upstream in waves through the coldest months and are well-conditioned, chunky, and bright. Downstream anglers call this run of fish the “ghost run,” because of the speed with which they move upstream through the system. They arrive today and are gone tomorrow.

Angling during the dead of winter can be slow and cold. Although a few fish are caught each day, winter steelhead fishing on the Klamath has a boom-or-bust character. Most epic days come during a few weeks in midwinter when the bite is unbelievable, but unfortunately also unpredictable. It often coincides with a warm spell, but not with every warm spell, and sometimes not with a warm spell at all. So the best plan is again to fish when you can.

How to Catch ’Em

If you’re going to go steelheading on the Klamath in the winter, the first decision you need to make is how you choose to play the game. Do you prefer to swing, bob, or swing and bob? If swinging flies is your thing, you must then choose between a floating or sinking line and between leeches and classic wet flies like Silver Hiltons. If you choose bobbing — I mean, indicator fishing — you must decide if you care to fish egg patterns or stick strictly to nymphs. If you choose eggs, you must also decide between securing plastic beads on or at the hook or limiting your game to Glo Bugs and other yarn-based imitations. The good news is that on the Klamath, unlike on many other steelhead streams, choosing any of these games will catch fish. We’ve enjoyed surprising success on a few occasions in the heart of winter swinging classic wets with a dry line. The bad news for purists is that a swung wet fly on a dry line will find fewer dance partners than a well-drifted egg, particularly as water temperatures drop into the lower 40s and colder. In order to have fewer decisions to make, on winter days, I cover all my bases and simply have two rods rigged, most often a single-handed rod with an indicator to fish nymphs, eggs, and ’legs (rubberleg patterns) and a switch rod with a fastsinking tip to swing leeches with classic wets as trailers. Hooks must be barbless. For swinging flies, I typically load a 4-weight regular rod or switch rod with a Skagit line and an 8-to-12-foot fast-sinking tungsten tip. The head and tip together will usually run 350 to 450 grains total. I add 3 to 5 feet of 10-pound Maxima and a marabou, rabbit, or Intruder-style leech that is two to four inches in length. I most often add a size 6 through 10 classic wet as a trailer fly about 30 inches off the hook bend of the leech. I have come to believe that darker colors most often work best, and I turn to bright flies only after I have exhausted my efforts with dark, buggy patterns. I must admit that I would likely catch more fish on bright flies if I fished them with more enthusiasm.

Most of the fish I hook when swinging flies in the winter are oriented to structure such as boulders in a run or are holding downstream from drop-offs. I find few, if any fish in the tailouts and riffles that produce so well in the fall. The fish most often hold deep in the run in the softer water, and getting the fly right in front of them is usually the best chance to get them to eat. For this reason, I prefer to cast from an anchored boat, rather than wade. The fly is simply moving through holding water for more time during the swing, and I believe this increases my odds dramatically. It has the added benefits of keeping my toes warmer and reducing my chances of falling in.

For nymphing on the Klamath, most folks select a 6-weight or 7-weight rod with a floating line and their bobber of choice. You can bring your special collection of steelhead nymphs, egg patterns, and rubberlegs, and you will likely find something that works just as well as the other guy’s assortment of special flies. Most fish are taken while side drifting from a boat through runs, deep holding pockets, and slots. Wading anglers can fish this water if they are able to wade within range. Again, the idea is to drift the fly right in the fish’s face, because cold steelhead prefer not to chase. This requires some line management and the ability to mend and feed line effectively. Most anglers can learn the basics of getting an adequate drift pretty readily.

What separates the most successful winter steelhead nymphers from the rest of us is their strike identification and their hook sets. On a good day of nymphing for trout, an angler might expect a couple of dozen grabs or more. A couple dozen grabs while winter steelhead fishing is considered awfully good, even for the Klamath. With fewer opportunities, it is important to take advantage of each and every one. In cold, slow, winter holding water, steelhead takes can also be quite subtle. The anglers who are best able to recognize a strike and quickly get tight to the fish are the ones who enjoy the dance most often. The key is to maintain a relaxed focus and to keep your hands in the best position to set the hook as you manage your line through the drift.

Klamath River Access

The most popular access on the upper Klamath is the drift from the hatchery below Irongate Dam down to the Klamathon Bridge (also called the Copco Ager Bridge) — and for good reason. The reason is that there is no need to find fish. The fish arrive in October and remain until the spawn in April. You merely need to find a way to get them to eat your fly.

Downstream, the next most popular drift is past the hamlet of Hornbrook to the Collier Rest Area on Interstate 5, roughly eight miles down from the dam put-in. The launch ramps are gravel bars, rough at best, and a four-wheel-drive vehicle is recommended.

Drifting the Klamath should not be taken lightly. While the whitewater upstream of I-5 is tame compared with the class III, IV, and V rapids and drifts found downstream, it can easily spook a boatman accustomed to drifting, say, the Trinity or the Yuba. The river has a lot of structure that is not easy to see or read. It is not at all uncommon suddenly to find oneself perched on a rock mid-stream — a rock that was all but hidden until you left a bit of aluminum gleaming on it.

Wading access upstream of I-5 is confined to a couple runs, because most of the riverbank is on private property. Public wade access below I-5 is quite good, with Highway 96 running on one side of the river and a secondary road running on the other from Ash Creek about 25 miles downstream nearly to the community of Horsecreek. Plan on enjoying this water by yourself. It is an event to encounter other anglers. So . .. tell me again: Why haven’t you visited? Shake off those winter shack nasties, fill up the tank, pack the rods, and repeat after me: “The best time to fish is when you can.”

If You Go…

There is little to be found in the way of amenities along this part of the Klamath River from its origins below Irongate Dam on down Highway 96, which follows the river downstream of the Interstate 5 bridge crossing. Most visitors base their trips out of Yreka, Ashland, or Mt Shasta. While Yreka is the closest town, it primarily features fast food and chain hotels. If you choose Ashland as a base, you’ll find lodging, dining, and entertainment options to rival any city of its size, but to reach the river, you’ll have to travel 25 miles south, crossing the Siskiyou Pass at the highest point on I-5, and the road sometimes closes during heavy storms. The majority of local guides reside in Mt Shasta, where their guests often stay and make the drive 45 minutes north to the river. The list that follows encompasses only local businesses — there are other guides and shops that feature the upper Klamath as a destination.

Craig Nielsen

Lodging

Hornbrook. Klamathon Lodge: A full-service lodge that includes guiding and all meals. For guiding and lodging packages, contact the Fly Shop in Redding, (530) 222-3555, Michael@theflyshop.com, or Craig Nielsen/Shasta Trout, (530) 9265763, Craig@ShastaTrout.com. Blue Heron RV Park: offers full hookups with water, sewer and 50-amp electrical, 3930 Copco Road, (530) 475-3270.

Yreka. Best Western Miner’s Inn: Conveniently located within walking distance from downtown eateries, 122 West Miner Street, (530) 842-4355. Baymont Inn and Suites: 148 Moonlit Oaks Avenue (530) 841-1300; near the Black Bear Diner.

Ashland. Plaza Inn and Suites: Within walking distance of downtown dining, shopping, and entertainment, 98 Central Avenue, (541) 488-8900. The Ashland Springs Hotel: A historic hotel in the downtown center, 212 East Main Street, (888) 795-4545.

Mt Shasta. Mount Shasta Resort: Chalets on Lake Siskiyou, 100 Siskiyou Lake Boulevard (530) 926-3030. Best Western Tree House Inn: A short walk to town, 111 Morgan Way, (530) 926-3101.

Guiding

Shasta Trout, Craig Nielsen, craig@shastatrout.com, (530) 926-5763; Andras Outfitters, Jim Andras, andrasoutfitters@me.com, (530) 722-7992; Wild Waters Flyfishing, John Rickard, john@wildwatersflyfishing.com, (530) 926-3810; Mount Shasta Anglers, Chuck Volckhausen, chuck@mtshastaanglers.com, (530) 859-3474; Three Rivers Guide Service, Alan Blankenship, alan@threeriversguideservice.com, (530) 925-7990.

Fly Shops

The Ashland Fly Shop, 399 East Main Street, Ashland, OR, (541) 488-6454; The Ted Fay Fly Shop, 5732 Dunsmuir Avenue, Dunsmuir, CA, (530) 235-2969; The Fly Shop, 4140 Churn Creek Road, Redding, CA, (530) 222-3555.

Shuttle Services

Sheri’s Shuttles, (530), 475-0931; Blue Heron RV Park, (530) 475-3270.