The first time I saw Roe Outfitters, I was blasting up Highway 97 on a motorcycle, heading from California toward Klamath Falls, Oregon. A charitable person might call this the “scenic route,” but the truth is, while it’s somewhat beautiful and very empty, a lot of this country seems somewhere to the left of Nowheresville.

Ten or 12 miles over the border, I noticed a funky little fly shop sitting by the side of the highway. It was shrewdly placed (note the sarcasm) next to an abandoned miniature golf course in the actual middle of Nowheresville. Although south-central Oregon is graced with a number of rightfully famous wild-trout fisheries, such as Klamath Lake and the Williamson and Wood Rivers, these are on the other side of Klamath Falls. All that seemed lacking here were buzzards circling overhead. I remember thinking, “ Whoever runs this place is nuts!”

A year or so later, I was on the same road and noticed to my amazement that the shop was still there. The place had obviously grown, and it was sporting a brand-new neon sign out front. Then it struck me. “Wait a minute. This guy knows something.” Indeed he does.

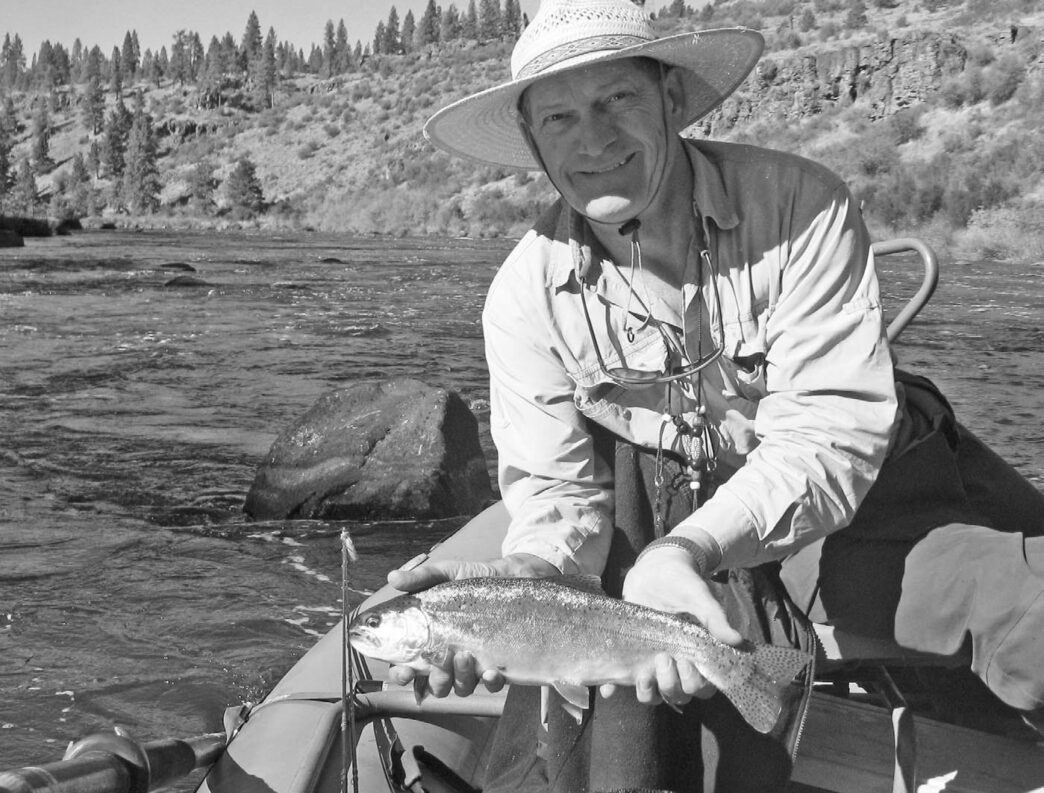

It turns out that Darren Roe, owner of Roe Outfitters, just south of Klamath Falls, is a fanatic — and just my kind of fanatic. Despite the success of his business, I wouldn’t necessarily credit him with discovering the Keno stretch of the Klamath River. This delightfully unusual fishery has been a favorite of stalwart nymph anglers with a taste for adventure for some time — mainly the southern Oregon crowd. Instead, Roe proved that with the appropriate suite of skills, this wild, raucous stretch of river can be safely floated, allowing access to water that hardly ever gets fished.

In fact, depending on the flows, this stretch of river is rated by whitewater enthusiasts as Class III+, meaning that it is “moderate to difficult.”The water often resembles someone’s colossal Starbucks frappuccino nightmare, and they obviously opted for the whipped cream. There is bank access, of course, but the opaque, swift water is more than capable of inspiring fear in even the strongest waders.

Yet in a twisted sort of way, maybe rafting here isn’t such a crazy thing to do after all. Floating allows you to sashay right past all those rattlesnakes along the bank. Any way you look at it, feel free to forego your morning coffee before fishing here. Adrenaline can be a worthy substitute for caffeine, and any day here offers basically as much as you might want.

The best times to fish this water are from May to June 15 and then again from October through mid-December. The river is open for fishing October 1 through June 15. It closes during the summer months to protect the fishery as the water warms up.

Not Just Any Trout

While they may look like generic rainbows to the untrained eye, Robert Behnke, in his scholarly work Trout and Salmon of North America, clearly identifies these fish as Upper Klamath Lake basin redband trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss newberrii. An ancient subspecies of rainbow trout, these fish evolved in and adapted to the large Pleistocene lakes that existed in this region for forty thousand to fifty thousand years.

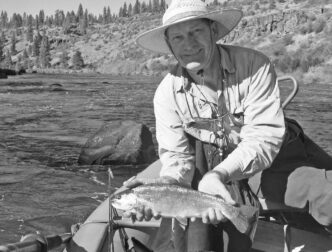

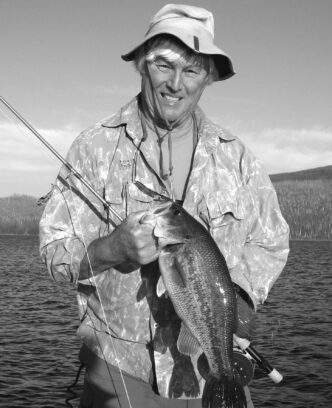

Thanks to the rampant stocking of hatchery rainbow trout in virtually every mud puddle and birdbath in the West, there are few truly pure strains of redband left, but these Klamath trout exhibit all the classic indicators of redbands: stout bodies, bullet-shaped heads, and rounded snouts. They have a pinkish stripe along each lateral line, with sparse spotting above it and few, if any spots below. Oregon biologists have always considered these fish to be redbands, while south of the border, in California, they “officially” call them rainbows, with a few dissenting votes. Regardless of what you call them, they are impressively frenetic when attached to the end of your line.

Something interesting happens to healthy fisheries that are pretty much left alone — in this case, thanks to frightening water and dangerous reptiles. The fish grow big, numerous, and while I would never insult a wild trout by calling it stupid, let’s just say they aren’t as selective as fish jaded by constant angling pressure. There is the potential to hook dozens of fish in a day here, and the average trout is longer than 16 inches.

Tactics, Techniques, Equipment

This is not a dry-fly venue, unless you count the maddening proclivity of these trout to inhale floating strike indicators.

For reasons only known to the fish, they seem to hit these far more frequently than dry flies. The most effective techniques are indicator nymphing with floating fly lines and streamer fishing with short sink-tip lines. Both techniques are equally effective, and the individual angler’s taste for adrenaline seems to dictate preferences.

For nymphing, hang one or two nymphs anywhere from 2-1/2 to 4 feet below an indicator, depending on the depth and speed of the water. If you try to fish deeper than that or use too many split shot, you risk spending precious time breaking off flies and rerigging. Some of this is to be expected anyway, as with almost all nymph fishing, but if you’re not getting bit in fishy-looking water, try fishing a little deeper. Either you will hook the trout that are most certainly there, or you will lose your rig and have to retie it.

As far as floating strike indicators are concerned, think big. You may not be fishing heavy flies, and with beaded flies, you won’t need split shot, but the roughness of the water conspires to sink all but the most buoyant indicators.

Longer rods will help you cover a wider area while nymphing. You can fish with shorter, lighter rods, but a 9-foot or 9-1/2-foot 6-weight or 7-weight rod works well. Leaders for nymph fishing should roughly equal the length of the rod, tapered to 2X or 3X tippets. Reels with beefy drag systems will allow you more control of wild fish when you need it.

My favorite way to fish this water is with streamers on sink-tip lines. If you have a taste for adrenaline and you’re pretty sure your heart checks out, this is the way to go. No matter how often it happens during a day of fishing, you can’t help but feel an almost electric jolt when one of these pisciverous submarines hammers your streamer. It’s tantamount to someone jumping out of the shadows and yelling “BOO!” When you feel the tug, your body knows exactly what to do, and you instinctively tug back, hard. Even on 14-to-16-pound-test mono, expect to break a few off. Short, fast-sinking heads work best, since a lot of the pockets you’re working are not that large, nor is there reason to cast all that far. Floating the river allows you to place yourself in a good position to work the best holding water well. Toss your streamer past and above the most likely spots, flip an upstream mend, point the tip of the rod at your fly, and hold on. It’s that simple. Yes, you will lose a number of flies in a day of fishing, but I’ve never met anyone who didn’t think the losses were well worth it. This is not a good place to fish if you are miserly about flies.

Access to the Keno Stretch

Those willing to risk the most stand to benefit the most, and the faint of heart ought to consider fishing elsewhere. Access to this place needs to be thoughtfully considered, and your boating and wading skills need to be accurately assessed. Boats used in floating the river will take a beating against countless boulders, and anglers without whitewater rafting skills need not apply. There may be times when you will need to dislodge the boat from boulders, which may mean getting out of the boat midriver in some fairly angry water. Not only are life vests required while floating the river, no sane person should consider fishing this run without one. Having a taste for risk is one thing, but dying of stupidity is quite another.

There is a good primitive launch just below Keno Dam. While pushing your boat through the reeds and cattails to get it out in the current, you can’t help noticing how brown the water is, and soon you will observe rafts of foamy suds on the water, some as large as floating sofas.

For fly fishers, the river is fishable below about 2,000 cubic feet per second. Lower flows are better for wading, but not necessarily for boating. These flows are most commonly found between July and December, but often at other times, too.

It’s a good idea to check the flows before heading out. You can find this information on the Westfly website, http://www.westfly.com/cgi-bin/fly-fishing-report-oregon-klamath-river, or by listening to PacifiCorp’s recorded phone message (800) 547-1501, or by phoning Roe Outfitters at (541) 884-3825.

To fish the Keno stretch of the Klamath, you first have to get to the tiny town of Keno. Driving north on Highway 97 from California, take a left on the KenoWorden Road. From Klamath Falls, it’s better to take Highway 66 into Keno. The best wading access is from the south side of the river off Highway 66, south and west of Keno. From Keno, drive until you see the big power lines going over the highway. Turn right (north) off Highway 66 and drive in as close to the river as you dare. It’s a fairly short hike in from there.

Wading staffs do a lot more than merely keep you on your feet in this river. They also make excellent walking sticks, allowing you to probe areas you can’t see into for rattlesnakes. The reptiles are not aggressive, and they certainly don’t want to deal with humans, but they are somewhat numerous here and may be large. That said, I’ve seen many more snakes on the McCloud River. Awareness and common sense will keep you out of trouble, and the snakes do an outstanding job of keeping the fishery marvelously vacant. They seem to be thickest during May and June, but it’s possible to encounter them on warmer days year-round.

If you don’t hire a guide, floating the river takes a little more choreography, since you need to park a shuttle vehicle at the bottom of the float. You can leave a vehicle at the Bill Scholtes Klamath Sportsman’s Park at the head of John C. Boyle Reservoir. (See http://www.sportsparkkeno.org.) To launch at Keno Dam, go north of Keno on Highway 66 and turn west on Clover Creek Road. Turn left on Old Wagon Road and proceed to the dam, where there is a rough boat-launch ramp.

Keno-Stretch Hatches

The entomology of the Keno stretch is somewhat less important to anglers than in waters that receive more fishing pressure. May and June offer Blue-Winged Olives, caddisflies, and a fairly significant damselfly hatch. Preferred nymphs include Ken Morrish’s Anato-May Nymphs and Super Pupa patterns. On some spring days, stonefly nymph patterns produce well, and Mercer’s Beaded Biot Epoxy Golden Stone, Mercer’s GB Poxyback Dark Stone, and Morrish’s WMD Nymphs are proven fish-catchers.

Since the fishery closes down during the summer to protect the fish during periods of higher water temperatures, the fall hatches are all that’s left. Blue-Winged Olives and October Caddises round out the seasonal trout menu.

The truly remarkable thing about this fishery, however, is that you don’t necessarily have to match the hatch. Presentation seems to be much more important than imitation, and a well-drifted nymph of almost any persuasion will attract attention. Fish that don’t get hammered on a regular basis just aren’t as particular.

If you want to fish streamers, the Keno stretch has a robust sculpin population, so just about any chunky, quick-sinking streamer will provoke grabs. Conehead Kiwi Muddlers, Sculpzillas, and the Morrish Sculpin are all good choices. You will quickly learn, though, that streamers with too much weight are prone to getting snagged. You will certainly lose flies here, so bring plenty.

The Challenges

When you’re floating the river, fishing doesn’t necessarily begin right away. Below the dam is one of the most elegant boulder obstacle courses I’ve ever seen, and you wonder how the you’re going to get your boat through it. In other words, not a wise time to fling a fly. In my mind, it is these gut-wrenching survival moments when you seriously ask yourself, “What the hell am I going to do now?” that define fishing this water. The good news is you get used to it and even begin to crave it, especially the rush you get when you hook one of these trout and it bolts for the fast water.

I said “hook,” but not necessarily “land.” These fish are hotter than a tire iron left on a pickup truck dashboard in Gehenna. Once they feel the hook, they are in the air — once, twice, and sometimes more. In the realm of freshwater trout fishing, there are precious few destinations where you actually have to worry about what happens after the hook is set. This is one. These trout fight with a sort of violence you can feel on a primal level, something like wild steelhead.

Depending on the flows, the river is white water in some sections and slower in others, and this will dictate how you engage the river. While drifting it, you will generally know when it’s time to quit fishing, strap everything down, and man the oars. It’s also best to err on the side of safety. Common sense says the slower sections are better for fishing, and the better pockets of softer water can often be found right up along the bank. Look for slower sections, especially if they’re close to anything that might funnel food. The fish are pretty much exactly where you think they should be, and where you find one, there are probably other likely candidates in the vicinity.

Down at the bottom of this stretch of the Klamath, the river flows into John Boyle Reservoir. Just before you get to the frog water at the head of the reservoir above Sportsman’s Park, there is another thrilling whitewater section to navigate. Once all of the excitement is past, and you realize you probably will not die today, the flow comes to an abrupt stop, and you experience a vertigo sensation something like stepping off an escalator.

The Thrill of It All

One recent October day, I made the 5-1/2 hour trek from my home to Klamath Falls after a long day of teaching high school. The last hour of the trip was in the dark in a dramatic fall rainstorm, steadfastly astride a motorcycle. I was one crazy guy about to meet another. The next day’s fishing with Darren Roe was outstanding. But the rain and the general sogginess of the day were relentless. Sometimes the water came from above, as rain buffeted and pounded us. Other times it came from below, as angry whitewater spray covered us. I worried that my non-waterproof camera was becoming an expensive paperweight.

In the end, it all worked out. We did not capsize the boat, and we landed impressive numbers of big, wild redband trout with unruly attitudes. After one more hit of adrenaline through the last whitewater drop, when everything suddenly slowed way down, we took a few deep breaths and rowed over to the takeout. That was when I realized just how tired I was and how much we had experienced that day. There had been so much activity and so much adrenaline. Dazed as I felt, I was already thinking about my next Klamath River trip, and that night, in a dry Klamath Falls motel room, I blissfully let a dream-born redband trout drag me into a good sleep.