A few days ago, one of the newer members of a fly-fishing club I belong asked me, “What stuff do you carry in your fishing vest when you fish for bass?” I answered with a short list of items that get added or substituted when I’m targeting bass or other warmwater species, and he walked away, seemingly satisfied. Later, though, I got to thinking about what I had said and realized that I’d shortchanged the guy with a partial list. As an aid for him, and for you, here’s the response I should have given.

First, you don’t really need to change the list of things you carry when switching from trout to bass or stripers, you just have to upgrade a few items to cope with larger and possibly angrier fish. To determine exactly what you’ll need, you have to think about how you are bass fishing. When I fish for trout, it is normally on one or another of the small streams that trickle through the local mountains. These are all different, but the fishing and the physical challenges of stream fishing in Southern California are all pretty much all the same, so there isn’t much change in the items I stuff into my vest.

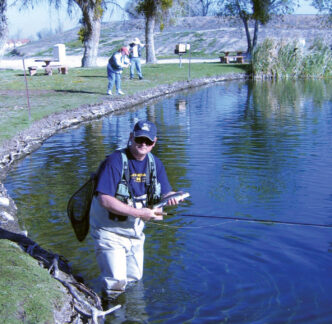

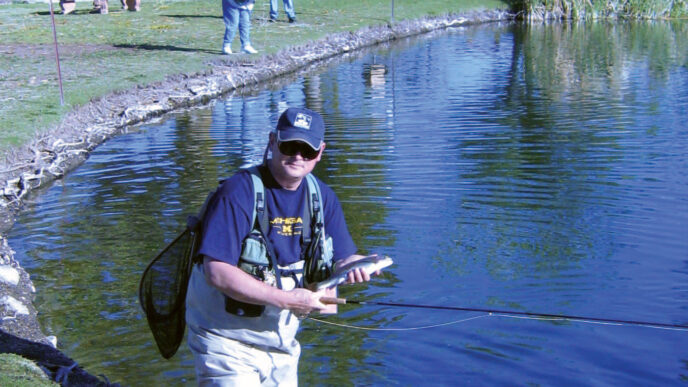

On a bass fishing outing, however, I may be in a boat, wading the shoreline, or sitting in a float tube. The water maybe a tiny pond or a huge lake. Each of these situations demands something different in tackle and gear. If I am fishing my favorite way, walking the bank of a small pond, I carry less gear than I do in a boat or tube, mostly because it isn’t that hard to walk back to the truck and get something I forgot or didn’t think I’d need. When fishing larger waters from shore, where you can walk or hike a mile or more, or when on a boat or in a float tube, you’ll want to make sure you have everything that might possibly come in handy.

One of the obvious changes for me is that on a bass pond, I carry spare reel spools rigged with different kinds of floating or sinking lines. When fishing small trout streams of the kind I have near my home, I can usually get by with just a floating line. Not so when fishing bass waters, or for trout in a lake, for that matter. Even the smallest bass ponds generally are much deeper in places than your average small trout stream.

While I’d much rather fish for bass with top-water bugs and poppers and a floating line, which is what I start with, much of my bass angling is going to be with flies and lines that sink to where the bass actually are. True top-water feeding sprees on bass waters are far less common than you might think.

I try to limit my store of spares to two spools. One holds a sink-tip line, the other a full sinking line. In the full-sinking category, I tend to choose fast-sinking lines even for small and relatively shallow waters, because bass are generally prefer to station themselves close to solid structure, and a fast-sinking line saves time in getting the fly to where bass might be holding.

Note that I said “spare spools” and not “spare lines.” I find it quicker and easier to switch spools than lines. I tried carrying a reel filled with backing and a running line, along with a handful of shooting heads, but finally decided it was too cumbersome for my tastes.

I also carry a couple of short lengths (about 24 inches) of lead-core line with loops on each end. With one of these, I can quickly convert a floating line into a sink-tip line, at least for moderate depths. If your line-to-leader connection is of the loop-to-loop variety, it becomes a simple task to remove the leader and add in the lead-core “head.”

Also, I don’t often put the longer leader back on when doing this quick conversion. Instead, I switch to a modest length of 8-to-10-pound mono, say 3 to 4 feet, which holds the fly down closer to the bottom. I use a longer leader with the sink-tips and sinking lines only if I’m fishing a bug or fly such as a frog pattern or Dahlberg Diver that I wanted to ride up off the bottom.

These short lead-core sections have saved more than one fishing trip when I discovered I’d left the spare spool with the sink-tip line at home. If I remember correctly, the largest bass I’ve landed while fishing a floating line affixed with a short lead-core tip was just over five pounds. That fish came from a trailer park pond. Fishing a bass bug on a full floating line produced nothing. Adding the sinking section turned the day around, resulting in the big fish plus half a dozen others that ranged from a slightly smaller four-pound fish to a couple of dinks that were not much bigger than the fly I was using.

Another change that I make when fishing for bass is the tool I use for hook removal. When on a trout stream, I clip a pair of hemostats to my vest in a spot that is easy for me to reach. Since all of my trout angling is catch-and-release with barbless hooks and the fish are generally small, as are the flies I use, these small surgical clamps work just fine for removing hooks from fish and occasionally from fishermen. Warmwater angling is another matter. I leave the hemostats at home and substitute a pair of stout six-inch needlenose pliers.

Needle-nose pliers work great as both a hook remover and as a general tool for emergency repairs of everything from reels, to boat motors, to pickup-truck engines. Their primary use, though, is for removing big hooks from big jaws. I often don’t fish barbless hooks for warmwater fish, and too many have bony jaws or tough, muscular mouths that require the application of more force to remove the hook.

The needle-nose pliers I use are just hand tools from the garage. They are not part of a Leatherman tool or similar item. Such combination tools are wonderful gadgets. I have a couple and used to carry one while fishing. Lately I’ve gone back to simpler, separate tools. The reason? Although multitools are useful, they’re also a pain in the tail to extract from a sheath or pocket and open to the function you need while you are struggling with a big, angry fish. I typically end up dropping them, sometimes in the sand or, worse, over the side of the boat. If you drop a multitool over the side, you’ve lost all your tools at once. A dropped single-function tool just means you’ve lost the use of that one tool. A pair of six-inch side cutters (also known as wire cutters or dykes) is another useful tool to have on hand. They will cut heavy monofilament leader material or the shank of a hook embedded in your flesh. This last is more of a problem in warmwater fishing than you might think. Bass flies and bugs are unwieldy things, just waiting for a chance to bury their hooks in the back of your head or some other painful place.

I used to know a fellow who fashioned huge rainbow trout imitations with long saddle hackles. These streamers were at least nine inches long and had a tandem hook near the tail of the fly, dressed on something like 100-pound-test mono. He hooked himself in the back of the head with one of these monsters one Sunday morning, and not having a pair of side cutters on him, had to go to a hospital to get the thing removed from his scalp.

In addition to the needle-nose pliers and side cutters, I like to carry a decent sized pocket knife when fishing for bass or other warmwater species. By “decentsized,” I don’t mean a pen knife, but a honest-to-goodness knife with at least a three-inch or four-inch blade. Note that this isn’t a survival knife, though it would certainly be welcome in a survival situation, but a tool. Any pocket knife will help you with a variety of tasks, from cutting leader material in a pinch to tightening a loose screw on a reel. I know a guy who saved himself and his wife from being stranded on a large lake by disassembling the upper end of a small outboard motor to replace a broken starter rope, using nothing more than a pocket knife of modest size.

Forgetting for the moment my admonition about multitools, my favorite knife is one of the tried-and-true Swiss Army models. It is a multitool in a very small package. Although it likewise isn’t easy to open while dealing with a fish, I carry it because it can help with a variety of problems. As an example, I own an old pair of wading boots that I when wading ponds and lakes. They have cleated soles and function much better in still waters than my felt-sole boots. One day while fishing Lake Perris in Riverside County, I felt the left boot loosen and almost come off while I was up to my waist in the water. One of the top eyelets had ripped out. With the Swiss Army knife, I was able to punch another hole for the lace, put the boot back on, and continue fishing. I’ve also used the knife to remodel a commercially made balsa bass bug so it did what I wanted it to do. In addition, I regard the knife as a safety item. Another safety item I carry is a small first-aid kit. You can purchase these little pocket kits for a buck at any number of outlet stores. They won’t have all the things you might want, but they are a place to start and usually provide enough space to add more of whatever you might need. In my case, it is Band-Aids. As a diabetic who takes blood thinners, every time I bump something, I bleed. A good supply of Band-Aids keeps me in the field.

Of course, these days, your cell phone should be considered a safety and first-aid item, too. In recent years, having my cell phone on the water allowed me to be rescued and to rescue another angler whose boat motor had given up on him. I don’t leave mine in the car anymore, but I often turn it off so I won’t be bothered. You always need to check to see what the signal strength is where you are fishing. When out of range of a cell tower, a cell phone will quickly expend all its batter power. Paying attention and turning your phone off when it is out of range will save battery life and possibly your life, too.

One of my oldest survival tools is a whistle. You’d be surprised at how much farther away you can hear a whistle than you can a human voice. I’ve never had to use it in an emergency situation, but it also comes in handy for alerting your fishing partner when he or she is a long ways off. Mine is a simple aluminum tube type with no moving parts. It cost less than a dollar. My days of making long hikes are behind me now, and I don’t fish a lot of fourpiece hiking or travel rods. That means coping with the longer two-piece rods. Even when taken down, a 9-foot or 10-foot two-piece rod catches on everything while you are moving from spot to spot on a pond. I think that bushes and vines sometimes will move just to tangle my rod while I am trying to reach a good spot from which to cast.

Recently, while fishing with my friend Keith Kern, I watched as he took down his rod. He reached in his vest and produced a tiny clip that he used to hold the ends of the rod together. When I asked to see it, it turned out to be a tiny hair clip from a dollar store. I promptly bought a few for myself the next time I was in town. You can get half a dozen on a card for 99 cents. Clipping multiple rod sections together helps you carry them more comfortably, especially in brushy or forested environments.

Speaking of brush, one of the tools that I carry both on the trout stream and at bass ponds and lakes is a small pair of garden shears or pruning shears. These are invaluable for getting into spots that are tight with brush or small limbs or for removing the small limb behind you that threatens your back cast.

In short, there aren’t many changes you might make in your bass fishing kit as opposed to what you carry for trout, but the few items that you should add will make a world of difference in meeting the challenges of bass angling.