Interest in stillwater angling with a fly rod is surging, with new anglers as well as longtime fly fishers broadening the scope of their sport from rivers and streams to lakes and ponds. While some fly anglers have fished still waters from the get-go, today, many are deciding that they want to invest the time to learn stillwater angling or to increase their skill levels and to try to master the complexities required for consistent success in an approach to fly fishing that has become surprisingly sophisticated.

Reasons for this surge include the increased access that still waters usually afford, the availability of larger fish in still waters, user-friendly opportunities for anglers with mild or even severe disabilities, and easily gained solitude. It’s also a way to fish waters that have less angling pressure than rivers and streams.

My angling club, the Gold Country Fly Fishers, has noted the increased interest in fly fishing for trout and other species in lakes and ponds, and in response, for one of our meetings, I put together an hour-long moderated panel that discussed stillwater fly-fishing techniques and strategies for anglers of all ability levels.

The panel and moderators were all expert fly fishers from our Sierra foothill region, and they each have decades of experience. Our professional members included licensed guide and writer Jon Baiocchi and local radio-show host and newspaper columnist Denis Peirce. Denis also owns Denis Peirce Flies. Angler participants included Don Liljeblad and Norm Sauer. Wayne Holloway assisted me in moderating the panel. We first met several times and came up with a list that could be used by the moderators to open up discussion at the meeting. These dry runs were exciting and mentally stimulating, and everybody profited from the experience. Our guide said, “I’m giving away secrets!” At the meeting itself, all panel members were asked a number of questions, including: How do you approach a stillwater venue? Why do you choose to fish specific areas and depths of a lake? What are the factors that influence your decision? Why do you choose certain times and techniques? What considerations come together in your mind as you try to solve the riddle? Some questions would be answered outright, others left for our audience to ponder.

We hoped to explain how to analyze a new stillwater angling venue to maximize success. We wanted to show why fly fishers congregate at Jenkins Point and Cow Creek on Lake Davis. We hoped to show the reasons why Snallygaster, Lunker Point, and Crystal Point fish well at Frenchman Lake and why big fish congregate at McGee Bay on Lake Crowley’ as well as when and why it’s time to look elsewhere.

Lake Davis is over 4,000 surface acres at maximum pool. Crowley and Eagle Lakes are even bigger, and with hundreds, if not thousands of smaller lakes throughout the West, it can be challenging to figure out where to go, when, where to find fish when you get there, and how to fish such a large and seemingly undifferentiated body of water with a fly rod. The advice that emerged from out panel discussion can help you meet those challenges.

Where to Go: Your Plan of Attack

Lakes in California are as dynamic and varied as moving water, but often in less obvious ways. They vary in type, chemistry, and fertility, as well as in latitude and altitude. The terrain and geology of the drainage basin surrounding a lake can range from alpine to high plains and desert. Choosing a destination that will gives a reasonable chance of success obviously is an important first step. Our first question was, “Where do you begin your assessment and plan of attack when fishing a body of water?”

Advanced anglers use every bit of information possible when sizing up the possibilities that a lake offers for fly-rod angling. Most start with books, maps, and periodicals such as California Fly Fisher and move on to current real-time sources on the Internet, including online streamflow reports such as Dreamflows (http://www.dreamflows.com) and fishing blogs. Next come phone calls to angling friends, guides, fly shops, and resort operators. Being advised to consult the latter brought laughs from the audience. We all know operators who know nothing but optimism: “Come on up. They’re knocking ’em dead. Guys are having twenty-fish days.” But our panelists also expressed skepticism about sources such as untended blogs and old websites.

You can usually trust the information from a good fly shop, though. In Grass Valley, our local shop, The Reel Angler, specializes in up-to-date information. Living in the heart of angling country, we have a great advantage in that our club members are out fishing a lot. Most of us have our regular “fishing days,” the way doctors have golfing days, in addition to fishing when opportunity knocks. We call in accurate reports to the shop in real time, and owner Tom Page passes that information on. “Real time” means a cell phone call from the Yuba at 10:00 A.M. and hourly updates of stream-flow information. Fish behavior can change from day to day, but a trusted, up-to-date report is invaluable, particularly when it includes specifics on water conditions and the presence of insect hatches and forage fish as they relate to fly selection.

What specific types of still waters did the panelists prefer to target? Although everybody likes a beautiful alpine lake, for fish numbers and size, they chose lakes in volcanic and alkaline soil drainages that are found in high desert terrain and the eastern Sierra. In Oregon, it’s the Cascade lakes and the lakes farther east. The same goes for Nevada. The reason is simple. Slightly alkaline water promotes aquatic weed growth, which provides shelter and food for juvenile and adult aquatic insects, which in turn need the calcium carbonates that go with alkalinity for exoskeleton development. The result is a larger forage base for the fish and more and larger fish per surface acre of water. A California Fish and Game document showed that California’s alkaline Lake Davis had a fish biomass of 200 pounds per acre in its heyday. Compare that with the fish biomass of a “good,” slightly acidic, alpine lake at 29 pounds per acre.

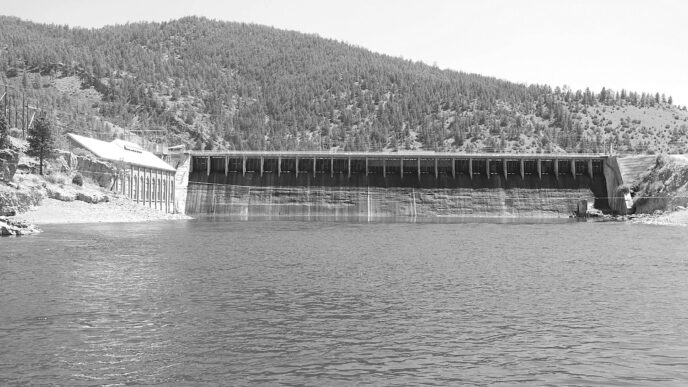

The panelists also preferred lakes with shoals and shallow water areas over bathtub-type impoundments with steep sides. Shoals are food factories because sunlight penetrates the water column to the bottom and results in photosynthesis that yields plant growth and corresponding insect development. That’s why California’s Lake Davis, Frenchman Lake, Bridgeport Reservoir, and Lake Crowley and Oregon’s Cascade lakes, Mann Lake, and Chickahomminy and Sheep Creek Reservoirs produce so well. Their unique conditions result in large fish and abundant insect hatches that promote surface feeding and sight fishing.

When: Time and Temperature

Our next questions for the panel centered on when to fish lakes or ponds. Obviously, the weather is one important factor. As they do on rivers and streams, changes in weather patterns can affect angling prospects both negatively and positively. Exceptionally wet or dry weather can bring high or low water levels, and these affect feeding patterns, with fish feeding in different places and at different times than they do in more normal conditions. Lake Davis can be hard to figure out in such situations — some say because of the changing depths of the weed beds.

Changes in weather patterns register in barometer readings, which always have been regarded as a factor to take into account when contemplating the prospects of a fishing trip. When I am at my Carnelian Bay home on Lake Tahoe, I call the Truckee Airport tower for current barometer and wind information before formulating my fishing plans. A low barometer slows down the action, but the leading edge of an incoming front can stimulate activity. Mackinaws (lake trout) love blustery, low-barometer days and will rise in the water column and go on the bite.

One general point that all panelists made is that stillwater anglers need to be willing to go fishing early and late in the season, even if inclement weather hinders willingness to brave the conditions. They pointed out that often early spring and late autumn offer periods of calm between weather fronts.

In the panel discussion, specific responses to questions about optimal times to fish still waters involved the varied relations between daily and seasonal light levels, oxygen concentrations, and temperatures throughout the water column.

All panelists agreed that bright light is an enemy of anglers. Fish don’t have eyelids and don’t favor bright light. Our panelists preferred to fish on days with fog or cloud cover, as well as early and late in the day and in the spring and the fall, when the angle of the light is low. Paradoxically, however, fish may feed best later in the morning during the spring, fall, and winter, because water temperatures will have risen as sunlight has penetrated the water column, especially along protected lee shores, where the water may be a degree or two warmer.

Fish seek out high concentrations of oxygen, and just as white water oxygenates stream flows, wind boosts oxygen concentrations, as well as creates surface currents and provides cover for feeding fish and fly fishers alike. As one participant said, “The wind is your friend.” Flat slicks amid a gentle chop and wind lanes can be fish windows. Work the center of the slicks and target the edges of the lanes.

As in steams, trout in still waters feed most actively when water temperatures are in an optimal range. Our panel’s consensus, after much discussion, was that the optimal range is from 52 to 65 degrees Fahrenheit. Below that range, the metabolism of the fish slows down and with it their interest in artificials. Above that range, trout are uncomfortable, and there is less oxygen, because warm water holds less. An accurate and sturdy thermometer therefore can be as important on still waters as fly selection. Instant-read thermometers are a great tool for determining surface temperatures.

However, everybody was careful to point out exceptions. There was agreement that above 68 to 70 degrees (and below 50), the bite slows, but all agreed that a 70-degree temperature reading at the surface can be misleading. What you want to know is what the temperature is 2, 4, or even 10 feet down, because fish will cruise 4 feet down in cooler, well-oxygenated water and rise to abundant insect food on the surface, retreating to a comfortable level before returning again to the surface to feed. If you use a fish finder on a boat, pontoon boat, or float tube, extend the probe so it gives you temperature readings at least 18 inches below the surface. And as one panelist pointed out, the important temperature is not always the one that the fish prefer, but the one that promotes insect activity. All agreed that fish will brave marginal conditions if there is an abundance of food available.

Both altitude and geography affect water temperatures. Higher-altitude lakes warm later, as do northern lakes. Prespawn bass activity at Stampede Reservoir, which sits at 6,000 feet, starts in May, whereas in low foothill lakes, it arrives in late February. Shallow lakes warm more quickly in the spring, as do the shallow parts, lee shores, and upper reaches of all lakes and ponds. Check out bottom contours on topographic maps or in person in the fall or during a low-water year. Some anglers photograph or video contours and shoreline for their angling libraries. Take it step further and put those sunken islands, shoals and creek channels in a GPS.

Unlike streams, many still waters “turn over” seasonally, and our panel addressed the effects of seasonal changes in temperature stratification in lakes on angler success. In the summer, as water at the surface warms, water temperatures decrease gradually as depth increases, but then a very rapid change occurs, with dramatically cooler, well-oxygenated water lying below this line or barrier, which is called the “thermocline.”Trout like the environment below the thermocline and hang out and feed there in the summer. That’s why trollers with deep-running downriggers do well during the summer doldrums. When fish are holding deep during the summer, below the thermocline, you still can find them in shallower water if you seek out springs. Sometimes a green seep patch on the shore will indicate a spring.

In the fall, the lake “turns over.” As the surface waters cool, they get heavier and sink. There is a compensatory upwelling from below, and at some point, water temperatures and oxygen levels are more or less evenly distributed, and trout and bass return to feed in the upper water column, often with abandon. This can result in superlative fishing. You want to be at a lake when this phenomenon occurs. Serious stillwater anglers save up vacation time for this event.

In the transition from winter to spring, a similar turnover occurs as surface ice melts and the heavier, colder water sinks. The prospects for fishing success therefore also go up then, and anglers should take advantage of this window of opportunity, as well.

Where to Find Fish

When you arrive at a lake, or even a pond, where can you reasonably expect to find fish? We’ve already covered a lot of the factors involved here: the season, water temperature, water depth, wind and wind direction, and the geology and topography of the area all play a part. With regard to topographical features that harbor fish, the panelists look for points or coves, shallow bays, shoals, mud bottoms that promote chironomid growth, weed beds, spring outflows, shoreline seeps, sunken islands, drop-offs, ledges, flooded timber, boulder fields, old channels, inlets, seasonal feeder streams, submerged roadbeds, outlets, dam faces, or just water depth.

They also look for wind lanes, foam lines (“foam is home”), mud lines, windward shores, currents, and slick patches. “Nervous water” caused by frantic schools of baitfish and V wakes, however subtle, suggest that fish are feeding just under the surface. “Bait boils” on the surface are another obvious sign of feeding fish, but advanced anglers know that the larger fish hang below a boil, waiting for chances at their smaller cousins or easy pickings on injured “sinkers” among the baitfish.

Bird activity, when present, is a huge help in finding fish, because they are likely to be feeding on the same food source. You could find gulls or blackbirds on a point waiting for damselfly migrants, herons stabbing minnows or frogs, terns feeding on shad or pond smelt, swallows taking Callibaetis duns out of the air, or grebes gobbling subsurface food. Diving ospreys and eagles signal that fish are in the upper water column. Nighthawks high in the sky indicate that something is hatching or has hatched and has risen in the air column. And don’t forget what you can learn from bats. Bats flying low at dusk tell of insect hatches.

The most prolific Callibaetis hatch that I have witnessed was at Smith Creek Lake in central Nevada. Thousands upon thousands of swallows took millions of popping Callibaetis duns. The water’s surface looked like we were in a driving rainstorm, with dimples everywhere. Large trout avoided competing for the hatching duns with the fast-dipping swallows by intercepting nymphs inches below the surface, but that morning, I saw a huge trout knock down a dipping swallow. Perhaps the swallow dipped too low. Perhaps the trout accelerated after the nymph, the way they do on an emerging caddis, and they collided. Who knows? But it was fun to watch and to contemplate.

How to Maximize Success

Once you’ve found a promising destination and have located places there where fish are likely to be, how do you go about fishing a lake or pond successfully?

First, by not fishing. Anyone who had the good fortune to fish with the legendary Andy Puyans probably remembers when a firm shoulder yank sat you on the ground and you were admonished to observe first, make an approach plan, then fish. And indeed, for over five decades, I have found that advanced fly fishers, regardless of background, have a common trait. All are keen observers.

Observation will help you determine what the fish are eating. To discover clues to that, it helps to have a sound knowledge of aquatic biology, entomology, and fish behavior.

Try to observe whether it’s damselflies, dragonflies, mayflies, caddisflies, midges, terrestrials, scuds, crayfish, leeches, annelid worms, water boatmen, snails, or other fish or amphibians that are present and seem to be what fish are eating. If you can’t determine that, go to generic searching patterns that an opportunistic fish may devour. Most of our panelists use two-fly rigs initially, because doing so presents two possibilities to the fish. Depending on what the first fish take, it’s then easier to settle on a particular imitation, depth of presentation, and choice of rigging.

Although the panelists all are keen observers, they noted that sometimes clues are few and far between. They agreed that such times require you to fall back on remembered events and background knowledge, whether gained on the water, from reading, from postmortems, or from shared information. They ask themselves, “Based on what I know, what should be happening under these conditions, at this time of the year?” Keeping and reviewing a well-maintained fishing log can alert you to possibilities that you may encounter again and things that you may have forgotten. It helps you to make a game plan.

Several panelists praised the use of sonar fish finders with horizontal and vertical scan capabilities and temperature readouts to find fish. Portable devices such as the Fishin’ Buddy, which mounts on a boat, float tube, or pontoon boat, operate on flashlight battery power and do not have the sensitivity of higher-voltage, more expensive, boat mounted products. They provide lots of information, though. Vertical shafts can be extended to give temperature readings several feet below the surface, and you can remove the unit from its mounting and stick it another foot or so deeper. I revel in the times when the horizontal scan shows “multiples” 55 feet away and a nymph or surface fly cast to that area produces a fish. Don’t believe the campfire rumor that sonar-device companies put in an “excitement chip” that randomly throws up fish blips.

If you are not into fish in a few minutes, it’s time to make some kind of change or to move. Two panelists follow the “10minute rule,” two more give a location 20 minutes. “If you have your act together and don’t get a hookup in that time, it is time to change something,” one said. It could be water depth, fly choice, line, leader, tippet, location, or presentation and retrieve.

This brings us to a discussion of gear, including float tubes and other ways of getting around on the water, and techniques of presentation for fly fishers. One of the nice things about stillwater angling is that it can be as simple or as complex as the angler chooses, and that includes how one accesses a lake or pond.

All participants mentioned that fly fishing from shore and close-in wading should be a first consideration. (See Jon Baiocchi’s article “Stalking Stillwater Trout” in the May/June 2013 issue of California Fly Fisher). All like to walk the bank, particularly early or late in the day or late in the season, when fish move inshore looking for food. Baiocchi, our guide panelist, specializes in stillwater shore angling and laments the lost opportunities of early morning anglers who launch float tubes, pontoons, and prams through productive, fish-holding water. They miss an opportunity, but also disturb the water for others. Often, aggressive inshore fish are the largest of the day. Although fish in thin water are cautious, they are also opportunistic. Trout or bass are there to eat, and more than one fly will work. An angler on shore need not give off waves, vibrations, or shadows and can be the stealthiest of fly fishers — and the most successful. Use shoreline vegetation such as logs, overhanging shrubs, brush, and trees as cover for your presence and let patrolling, cruising fish come your way.

All the panelists like small personal watercraft such as float tubes, pontoon boats, and prams for ease of access as well as for considerations of cost and stealth. Fish can be disturbed by boats, pontoon boats, float tubes, and prams, though, and longer casts can be required because of the reluctance of most fish to take an artificial in close. Being stealthy and keeping a low profile on the water is always good, even in a floating device. One technique is to be very still and let fish come to you, rather than disturb the water by chasing after them.

Of course, “messing about in boats” can be one of the most enjoyable parts of fly fishing still waters. The range that a boat gives is of immeasurable value, and so is the ability to carry a lot of gear, including a rain jacket, a thermos of hot coffee, a pee bucket, half a dozen rods, and 10 fly boxes. When it came to rods and terminal tackle, the panelists were often in agreement. They thought that reel choices are less important than the choice of rods, lines, and leaders. Matching a quality rod with a quality line facilitates good casting skills. When the budget allows, a reel with a good drag mechanism can be added. You need that drag when fish start being measured in pounds. Our group fishes still waters for trout with 5-weight or 6-weight medium-action rods, and the 6-weight will work with bass, as well. Medium-action rods are more forgiving and cast a variety of fly weights and sizes. If you get serious about bass fishing, however, specialty rods will cast larger, heavier flies with accuracy and ease. See my article “Gearing Up For Bass” in the March/April 2012 issue of California Fly Fisher All but the lowest-priced modern rods cast well when compared with older-generation equipment. A respected fly-shop proprietor will steer you in the right direction.

All the panelists recommend carrying at least two rods, one armed with a floating line and another with a clear intermediate — maybe even a third with a faster-sinking line. Guides and advanced anglers carry multiple rods already rigged up, because they want to be able to get their lines and flies in the water quickly to capitalize on events as they happen. Long periods of inactivity may be followed by short bursts when quick action may snare several fish and make a day. You have to be ready in seconds, not minutes.

The panelists also preferred pliable, supple leaders, and all go longer and lighter when in doubt. A 9-foot leader tapered to a 4X tippet is a good starting point. Add 4X or 5X tippet when you lengthen it. The panelists use fluorocarbon primarily for leader tippets for subsurface flies — none of them pay the exorbitant price for full-length fluorocarbon leaders. Fluorocarbon sinks at two to three times the rate of nylon, and they value it for its density and abrasion resistance more than for its heralded “invisibility.” It is unnecessary when fishing floating flies, however. Many novice or intermediate anglers are afraid of long leaders, but our experts prefer them and say that they aren’t a problem with top-quality, balanced rods, lines, and leader configurations and lots of practice.

This brought up the issue of casting skills. On still waters, you can catch fish just by back-trolling a fly from a float tube, but to maximize success, you need viable casting and retrieving skills. Casting skills are important both for covering water and getting a fly out to boat-shy fish, and fly animation is essential when you get into sight fishing for rising fish.

Most hits come on longer, well-laidout casts. The ability to cast moderate to long distances increases the chances of keeping your fly in the zone as long as possible and multiplies the amount of water covered. The difference in water covered between a full circle of 50-foot casts and a full circle of 60-foot casts is approximately ten thousand square feet. Both our guide and our experienced anglers spoke of the rewards of helping anglers with casting skills, and the frustration of having a client who has few skills and doesn’t practice before a trip. If you fish out of a float tube, pram, or pontoon boat, practice casting from a chair on a lawn or even sitting or kneeling on the ground. Faster-action rods and weight-forward lines can help increase the distance of your casts.

The panelists also emphasized understanding the capabilities of your fly rod and fly line as they relate to fishing various depths in the water column. It is essential to know how deep your fly gets on an average cast and retrieve, and once you have identified the feeding zone and how to reach it, how long you fly stays in it. I remember a club outing where we tested the sink rates of lines in a swimming pool to understand what was really going on. They didn’t sink as far as we thought, and it took longer to get to the depths we targeted. Don’t speculate — do your own testing and understand how your own lines behave. It’s all about keeping your fly in the zone for as much of your retrieve as possible. Leader length and tippet diameter determine whether your fly will rise above your line on a retrieve, just trail behind it, or sink below that level. The weight of the fly also helps determine how long it remains in the feeding zone. There used to be a lot of guesswork involved in adding weight to flies, but in Becoming a Thinking Fly Tier, Jim Cramer has researched the effects of different weighting methods on flies, comparing the weight of lead wraps with that of different density beads and dumbbell eyes. So if you tie flies, you can fine-tune your flies to match the presentations you want to make. And speaking of presentations, fly animation as determined by manipulation of the fly during retrieves is what separates great anglers from the pack in stillwater angling. You need to imitate the movements of the specific insects, crustaceans, baitfish, or other food forms that your flies represent. Study insect behavior and adjust your retrieve to your bug’s profile. Ralph Cutter goes underwater with his mask and camera. Others capture insects and observe in home aquariums. Underwater videos will open your eyes.

Emerging aquatic insects tend to rise and fall on their way to the surface and to swim in bursts. Some crawl on the bottom, looking for a physical avenue to the surface. Midge larvae bounce up and down. Leeches accelerate and stop and accelerate again. Damselfly nymphs swim with a sinusoidal, sidewinder rattlesnake movement. Motorboat caddises buzz and scoot in all directions.

Our experts said that nothing frustrates them more than watching an unsuccessful angler execute the same retrieve over and over, all day long, with the same line, leader, and fly combination, fished in the same area. However, all agreed that when it comes to retrieves, slow is better. Before changing flies, they slow down their retrieves. After all, how fast does a Callibaetis nymph or damselfly nymph swim in miles per hour? Not very fast at all. When you and your fishing buddy have identical gear, including lines, leaders, and flies, and he or she is successful and you are not, usually it is because you are retrieving too fast. And fast retries also affect fly depth. I admit to being a contrarian on occasion and “rippin’ ” my flies if a slow retrieve isn’t working.

To build a selection of flies that will maximize success in still waters, start with imitative patterns that mimic the insects and other fish food that, via your planning, you’ve determined are right for where and when you’ll fish. Read and watch videos. But once on the water, if observation yields no clues to what the fish may be eating, you’ll do best by fishing generic patterns. See the sidebar for a list of patterns that would stock a collection of fly boxes for successful stillwater trout and bass angling.

Over half of our participants use twofly rigs when searching for feeding fish. Often it is a cinnamon, olive, or black Woolly Bugger trailed by Denny Rickard’s Stillwater Nymph, by a midge pattern, or by a Sheep Creek Special. We also fish imitations of beetles, cicadas, grasshoppers, ants, and termites on the surface with midge droppers. Our panelists find midges (Diptera) in larval, pupa, and adult form to be the overlooked aquatic insect, though. They are the most important food form throughout the year.

Be Safe Out There

Our evening ran over the allotted time and ended too soon, but before it did, our participants wanted to bring up stillwater safety, and so do I. Hypothermia, dehydration, and heat exhaustion all are possible threats to the well-being of the stillwater angler. Overdress for cold water — if you’re in a float tube, you’ll be sitting in it for hours. Hydrate well and watch your blood-sugar levels. Plan exit strategies before entering the water. I’ve had to walk out of a few situations, and I like to wear booties or lightweight wading boots under my flippers that allow me to walk significant distances in case of a forced bailout. Carry a signaling device such as a whistle, as well as a small flashlight. And keep an eye on the weather. Float tubes, pontoon boats, and prams are very vulnerable to weather changes and sudden winds. Wear personal flotation devices. Cell phones or walkie-talkies are a good idea, too. There’s a reason for the buddy system.

Whether you’re walking the shore of a trout lake in the morning or the margin of a bass pond at dusk, and whether you’re fishing the damselfly hatch on Lake Davis or casting to largemouths from a float tube on a warmwater reservoir, fly fishing still waters opens up angling opportunities. If you’re one of the fly fishers who fish only rivers and streams, it’s worth finding out what you’ve been missing. The panel that our fly-fishing club put together shows you the best way to get started.

A Stillwater Fly Box

The best fly to fish, always, is the one in which you have confidence. The anglers on our panel all have go-to flies that they fish with confidence in particular situations. What follows is a list of fly patterns, in no particular order of significance, that we carry and fish with in the still waters in our area, which include both the western and eastern Sierra. I’ve included some bass flies, as well, and as there is overlap in the habits and habitats of stillwater trout and bass, a basic fly box will do double duty for both.

These patterns would be a good start in putting together any stillwater fly box:

Callibaetis mayfly nymphs, emergers, duns, and down-wing spinners, size 14 to 18 Cicada foam imitations with white hair wings as a primary fly with a dropper Woolly Buggers, Krystal Buggers, Semi Seal Leeches, and Seal Buggers in olive, black, and brown or cinnamon, size 6 to 12

Sheep Creek Specials, size 12 to 16

Damselfly nymphs in olive and tan, size 10 to 16. There is tremendous local variation here.

Damselfly adults

Dragonfly nymphs in olive or brown, size 8 to 10

Jay Fair’s Wiggle Nymph in cinnamon and olive, size 8 to 12

Mink and Pine Squirrel Leeches in olive, black, and brown, size 10 to 14

Ant, termite, and beetle imitations, size 18 and up

Adult midge imitations such as Griffith’s Gnats, Cutter’s Martis Midges, Blood Midges, and Spotlight Emergers. There are many variations here, going as small as size 20

Midge pupa imitations such as Zebra Midges, Disco Midges, small Copper Johns, Serendipities, and many more, typically size 16 to 18

Black AP Nymphs, size 10 to 18

Bird’s Nests in olive, black, and tan, size 12 to 16

Adult caddis imitations, such as the Elk Hair Caddis and Cutter’s E/C Caddis, size 14 to 16

Denny Rickard’s Stillwater Nymphs in olive and tan, size 10 to 16

Classic bass patterns include:

Buggers of all types, leeches, and rabbit-strip flies

Crawfish patterns

Damselfly and dragonfly nymphs and their adult floating versions

Gummy Minnows

Frog patterns

Poppers and sliders in chartreuse, yellow, and black

Clouser Minnows

Trent Pridemore