I send an e-mail to my friend Fran Noel, the artist and inveterate angler, asking if he might share one of his low-water steelhead patterns that he’s been refining each fall since retiring from teaching, with maybe a print of the fly like the one used on the cover of my last book.

Fran, it turns out, is whiling away a summer’s week on Silver Creek — the Silver Creek, in Idaho. He’d love to help, he says, as soon as he’s home — a response, sent from a smartphone, filled with the spelling errors and egregious grammar of a teenager.

Or a former art professor who’s been at it all day on the water. No rush, I reply. I imagine that stretch, just below the footbridge, where big rainbows smile and shake their heads as your fly drifts teasingly overhead. By the way, what are they eating?

Fran’s answer arrives early the next day. Brown Drakes in the morning, mostly Pale Morning Duns around noon to two. The occasional beetle and Callibaetis. “Fish are fussy,” he adds, “but a few can be fooled.”

Attached is a blurry image of what appear to be some freshly tied PMD cripples — turkey-flat wing posts and sparse parachute hackles.

“Good-looking bugs,” I type.

Then, as an afterthought — picturing again those snooty fish sneering below the footbridge — “You ever tried an IOBO?”

Maybe he didn’t see the article. A couple of years ago, in this same magazine you’re reading now, I wrote a piece about my introduction to the IOBO, a pattern passed along to me by another friend, the great and stylish trout angler and cane-rod aficionado Bruce Milhiser. Bruce — along with his wife, Linda — lives for opportunities to fish over big, wary trout, often turning to delicate, nondescript soft hackles fished on the surface exactly as if they were dry flies. Bruce slaughters tough trout. So when he mentioned he’d added a new style of fly to his already deadly lineup of soft hackles, I figured I should pay attention, even if I profess, ad nauseam, that it’s not about the fly, that an angler such as Bruce Milhiser catches more and better fish because he’s a more and better fly fisher.

Still, how can anyone ignore a fly with a name distilled from the line It ought to be outlawed?

Apparently, plenty did. To date, Bruce and Linda are the only two anglers I know — besides myself — who faithfully fish this funky pattern.

Which poses one very big question: What are you waiting for?

My phone rings just as I’m about to sit down to dinner. I consider ignoring it, only to remind myself that since my last sweetheart vanished, it rarely rings anymore.

“Fran Noel.”

An odd greeting. Did I call him?

“I can talk a lot faster than I can type.”

Fran, I should add, is old enough that he hasn’t been using digital devices his whole life. Unlike me, however, he seems to enjoy them, perhaps because they’re so different from the heavy mechanical implements he’s used so long as a printmaker. I remind myself that he is also one of those ageless guys who still ends up on the awards podium after a ski race and, afterward, demonstrates a sophisticate’s pride in his ability to fashion a martini.

“What’s with that fly anyway?”

“Why?” I ask. “What happened?”

“What happened is I looked it up online and tied a few — and about the third cast, I started catching fish.”

He likes the name nearly as much as hooking heavy trout all morning. He’s already called his wife, knowing she’d get a kick out of it, too.

“Any size?”

“I had two big fish to my feet. Lost them both while trying to video.” “Serves you right,” I say.

What’s with that fly, anyway?

Many favorite patterns, both old and new, raise this question, even though by now, we should all be keenly aware that there’s an alchemy at work in all good flies, a mysterious balance between a host of different aspects made to look like something we think a fish wants to eat. Size, shape, color, movement — these are what most of us see when we gaze at a fly, imagining how it looks to the fish we hope to catch. Yet nearly everybody knows by now that were someone, with the aid, say, of digital imagery and CAD/CAM micro-milling techniques, able to reproduce an exact replica of a Callibaetis spinner, it would end up catching as many trout as the imitation of a penny.

Good flies are much more than we see or know or understand. After they work, we have all sorts of reasons for their superior performance, and with enough experience, we can, on occasion, predict whether a new fly has a genuine chance to make its mark in the sport. But mostly we’re all just guessing. Say what we might, the only proof that exists is the pudding.

There’s no good reason, really, why year after year, a little Gold-Ribbed Hare’s Ear outfishes every nymph this side of a Copper John — another fly with nothing exceptional going for it except that it works whenever and wherever there are nymphing trout. Now that the Copper John — or some variation of it — is the world’s most popular nymph, guys can write dissertations on why the pattern works so well, although only rarely do you hear anybody talk about how the Copper John’s efficacy is linked, to a large degree, with the development of modern tight-line nymph-jigging techniques.

Dry or surface patterns pose their own mysterious appeal to feeding trout. No matter where we are in our careers, most of us are still pretty sure that an Adams, tied how we like to tie them and in the appropriate size, will take care of almost all of our needs for a mayfly dun — especially if, not only in sizes 12 to 22, we tie them in a range of colors.

But then it’s not an Adams, someone will claim.

That’s sort of the point. If you tie a Parachute Adams, or a No-Hackle Adams, or a Hairwing Adams, and you fiddle this way and that with colors, you end up covering most all your mayfly dun needs — regardless what you call your flies.

Most — but not all. Time and again, with trout rising, taking bugs on or in the surface, we find ourselves frustrated, unable to elicit a hit. We’re all pretty sure what we need now is some sort of emerger pattern — that the trout are taking something trapped, if only momentarily, by the membrane between water and air. If we’ve been paying attention, we know that a wide range of simple soft hackles fished right in the film can save the day — as long as we fish them with the finesse of a brain surgeon.

What you might not know — and what Fran Noel, for example, didn’t know until he tried a few on Silver Creek — is that this is the time and place for the IOBO, named specifically because it works, more often than not, better than any fly ought to.

Take a look at the picture, and once again, you may ask yourself “Why?” What’s the deal? One feather. Crude profile. Color and texture of a dirty dishrag. It looks about as interesting as a . . . bug. Don’t be deceived. The IOBO, specifically the Humpy version shown and described here, doesn’t work because of its looks — at least because of how it looks through our eyes when we see it out of or even on the water. Or at least, I don’t think that’s why it works. My thesis is that we don’t know — that our reasons why our flies work, however sound, are incomplete; that for all the new ideas and new materials and new techniques and flies, very few patterns, new or old, have what it takes to make a genuine difference in anyone’s fly box.

Still, the consensus regarding the original IOBO and its several derivatives, including the IOBO Humpy, is that nothing else in the fly tyer’s vast array of materials works quite like cul de cunard, otherwise better known as CDC. European tyers seem to have a special affinity for the stuff, yet it was Jack Turner in Pennsylvania who first developed the all-CDC fly that he eventually called the IOBO because — well, you know the reason behind the name.

The one thing everyone should know about CDC feathers is that they grow at the base of a duck’s tail, the location of the gland that produces oil to keep duck feathers dry. This oil saturates CDC feathers. More important, however, is the structure of the feathers themselves. Tiny barbs cover the plumes extending from the center quill of each feather, dramatically increasing the surface area of each plume and its capacity to trap and hold air. The result: a “hydrophobic” feather, rather than a feather that absorbs water. CDC feathers offer a mechanical advantage to flies fished on or in the surface film — but, again, I hesitate to claim that this is the secret to the IOBO or IOBO Humpy.

What we do know is that the fly works — that it catches tough trout in tough situations. I suspect some anglers don’t like that it takes only a couple of fish before the fly can look pretty ragged — and the nature of CDC is that you have to dry the fly, rather than treat it with floatant, should it get slimed and soaked from fish.

My response to these complaints is that tough fish are generally big fish, and it takes just one to remind you why you enjoy the sport so much. Bruce Milhiser catches oodles of tough trout, and more and more, he says, the IOBO Humpy is his “fly of choice.” Simple, quick, no flash, nothing fancy: “It catches trout, not fishermen,” he adds.

Materials

HOOK: Dry fly, size 16 to 20

THREAD: 8/0, color to match CDC feather

BODY/BACK/WING: One CDC feather

Tying Instructions

There’s a column waiting to be written about how we learn to tie flies today, especially how so many of us watch on-line videos to find out how to tie new patterns. The world of fly fishing really has grown small. The sad part of this phenomenon is that the constant and almost immediate cross-pollination of fly patterns and fly-tying techniques often comes at the expense of the regional breeds of patterns that were once such a quirky and vital aspect of the sport. This is no place to talk about the threat of homogeny in fly fishing and in culture at large, other than to mention the excitement I still sometimes feel when I open the box or wallet of a traveling angler and see patterns I’ve never seen before — patterns that stir me at some profound, liminal level, inviting me to approach challenging fish in new and unexpected ways.

That said, I can’t recommend highly enough the IOBO Humpy tying video by Hans Weilenmann, v=jbUCtVGY6Ok. There’s not much to tying this homely fly, but I love listening to Weilenmann’s Dutch accent, the way the th in his the and then and those can sound like a d, producing a tone of gravity that gives the IOBO the weight of a device developed by advocates of secret weaponry. “This silly-looking pattern,” says Weilenmann, “is just utterly devastating.”

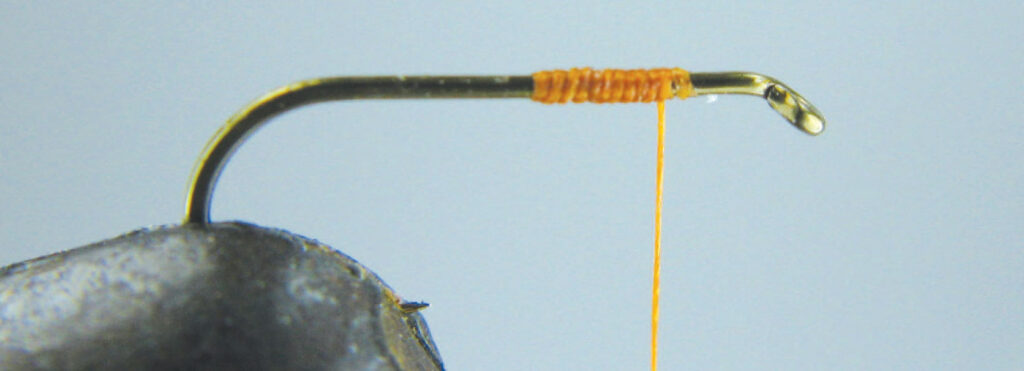

Step 1: Secure your hook in the vise. Start your thread near the eye, wind back to the middle of the hook shank, and then return to the starting point.

Step 2: With the tip curving forward, secure the butt of a single CDC feather directly behind the eye of the hook. The quality of CDC feathers varies greatly, as does the length of the plumes. Don’t sweat it. The trick at this stage is to cock the feather so that it ends up more perpendicular than parallel to the hook shank, using wraps of thread in front of the feather’s stem, as well as behind it. This angle helps prevent the thick butt of the feather from breaking when you start winding the feather onto the hook.

Step 3: Wrap your thread to the bend of the hook. Holding the tip of the feather in hackle pliers, begin winding the feather toward your thread. As you wind, stroke any loose fibers toward the hook bend; try to trap the fibers under the wraps of the feather itself. At the start of the hook bend, secure the feather with a couple of turns of thread.

Step 4: Advance the thread in an open spiral to the head of the fly. Take hold of the clump of feather fibers extending from the butt of the fly and pull them forward, creating the Humpy profile. Lock these fibers into place with a couple of thread wraps directly behind the eye of the hook.

Step 5: Create the wing by pulling the fiber clump upward and holding it vertical with thread wraps (see the completed fly on page 21). Once the wing is in place, simply whip finish. That’s it. Some tyers fuss about loose fibers extending from the body or butt of the fly. Others trim the wing tips to a uniform length.