The adrenaline rush of getting to the water often causes us to overlook shallow inshore areas that can be very productive for fly fishers. There is a natural tendency to launch a float tube and kick for the far bank or plunge into a stream and wade up to our chests. In our excitement to get to the water, however, we often terrify fish that are feeding against the shore, right beneath our noses. Here’s a thought: Don’t step on the fish!

Lessons Learned

I learned the hard way the importance of observation from my first mentor in fly fishing, the late André Puyans, guide, legendary educator, fly-shop owner, treasured friend, and developer of the famed A.P. Nymph series. In the early 1970s, Andy invited me to fish with him on his early-season pilgrimage to Hat Creek. We picked a week when we could expect prolific morning and evening hatches. I was new to fly fishing and as excited as they come, and I rushed into the water as soon as I got my waders on and rod rigged. A huge hand grabbed my shoulder, and I was led 30 feet back from the bank, where I was sat down and lectured on observation first, fishing second. Andy slowly and methodically charged and lit his carved meerschaum pipe, rolled his eyes under those dark, brushy brows, took a few puffs, and gave me a stern dressing down and a valuable lesson that has stayed with me for a lifetime.

That class on the bank, well down below the now defunct Carbon Bridge, changed my approach to fly fishing. Andy let his eyes adjust to the water’s glare and then studied the trouts’ underwater movements for a long time. If fish were taking on the surface or in the film, he knew from the move to the bug and the rise form what insects were present and being eaten. Hat Creek, like other rich spring creeks or fertile tailwaters, often has multiple hatches occurring simultaneously. Different age classes and species of fish may feed on different insects and on different morphological forms of those insects, and the pattern can change in a minute or two.

If feeding was occurring in the lower water column, Andy knew his lanes between the waving emerald weeds and where he wanted to fish. Before he entered the water, he had plotted his route to the streamside, knew where the bigger fish lay, which ones to try for first, and what insect imitation to tie onto the tippet of his leader for his initial attempt.

Often his first cast came while he was standing or kneeling on the bank, and only his leader hit the water. When I charged into the river that first evening, I had committed the unpardonable sin. It cost me several bottles of wine and camp duties for a week. Angling partner Hal Wilson and I received another early lesson on Montana’s Big Horn River in August 1988. We left our lodge at Fort Smith near the base of Yellowtail Dam at dawn and were charged with excitement as we helped our guide launch his drift boat into the Holy Water. Both of us had fished with guides only a few times. To our dismay, he stroked strongly on the oars and made a beeline down the river, passing up what looked like excellent water. How were we going to cast to fish moving this fast? We weren’t! We were heading toward a place that he knew would hold inshore midge feeders on that calm morning.

After we had left a mile of river behind, Hale, our guide, swung to the outside of a long, slow bend and back-rowed to put us ashore on the inside of a sweeping run. He then gathered Hal and me on the beach and gave us a long instructional lecture. He told us that the fish were in 6 to 18 inches of “soft” water along the inside edge of the bend. We learned to rig a 9-foot 4X leader with another 4 feet of 5X tippet and place one twist of matchbook twist-on lead above the Blood Knot. He then tied a size 20 black Brassie to the business end and placed an aspirin-sized pinch-on Palsa foam indicator on the leader.

Hale led me up the bank and paused to study the water for a long time. We moved again, and he nudged me into six inches of river. Mist still rose from the surface, and a vertical finger to his lips quieted my chatter. He whispered, “Don’t slosh around. Stand on the inside edge and stay still.” He directed my first cast 45 feet straight up and parallel to the gravel bank. I was to fish the rig all the way back to my rod tip, taking in slack as my line came back toward my position, lifting my rod tip gently if I saw any interruption of the indicator, however small.

I missed the first take. The indicator’s change from a drag-free drift was so imperceptible that it didn’t register — nor did the second one. I saw the third and lifted as the guide signaled. A 20-inch brown football pushed a wake as it moved laterally, broached, and porpoised for deeper water and the far bank. Halfway out, it broke water again and tail-walked on its journey toward the far shore.

Hale turned and walked back toward Hal. He yelled to me,“There’s fifty fish above you. Take your time.” He moved downstream to get Hal started and returned 15 minutes later to instruct me on the nuances of this technique. I learned to adjust the amount and position of the twist-on lead and the position of the pinch-on indicator for water depth and current speed. As the morning mist dissolved and a late-summer sun rose higher, our fish moved gradually out into the run, but not far. They were feeding on dense clouds of drifting midge larvae. As long as I didn’t disturb the fish by walking through the pod or sloshing like a thirsty cow, I could take one trout after another.

We fished the Bighorn a second day with Hale, and he found more fish on “soft insides” when other boats weren’t doing well. Later that day, he found trout feeding on emerging midges . . . again in thin water. We greased our leaders to within six inches of small, dark midge pupa imitations and cast upstream, striking with a gentle uplift on barely discernable bulges in the mirrorlike surface of the water.

Hal and I headed out the following day on our own in a rented drift boat and once again found fish in shallow water. Back at our lodge, over a late-evening meal and cocktails, we listened to other anglers bemoan the lack of working fish and the warm-weather midsummer doldrums.

We used that same technique often on the rest of our two-week Western angling safari at a time that brought low water levels and high temperatures. Now I always carry a packet of the “little aspirin pills” in my leader pouch. A large indictor and heavy split-shot will often spook nearshore fish.

The lesson was repeated a few years later on the Madison. I was a guest of Gordon and Penny Storjohan at their enchanting streamside West Forks home. Gordon mows the grass and shortens native brush back from the river so his visitors have a clear back cast. A wooden swing gives a resting angler a view of the river with a glass of wine in hand. That summer day started out pleasantly, and early afternoon temperatures built into the low 80s. After lunch on the streamside deck, billowing Montana thunderheads swirled out of the Gravely Range. Torrential rain, lightning, and sub-50-degree air drove us inside. I woke from a good nap and grabbed my rigged rod for a shot at several “house fish” in the poststorm low-ceiling calm and fading light. Somebody else had beat me to my spot, though. He had worked upstream from a home on the flat below and was kneeling in the streamside grasses and casting a micro-indictor rig tipped with an unweighted nymph. I watched him land two 19-inch browns. It left an impression.

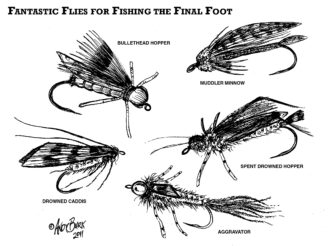

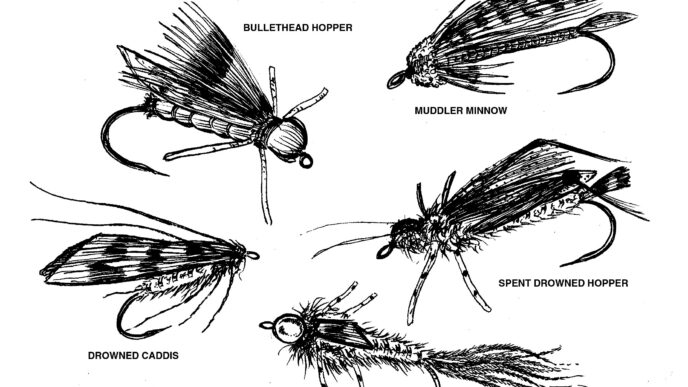

In my numerous visits to the Storjohan’s compound, I gradually learned to look for fish in shallow water, and successes came more often. During August “hopper” time, in broad daylight, large fish will lie close to the bank in the inside seam where water surges around the head of islands. It’s easy to scare them while wading to a “better” spot. The lower base of shallow riffles also hold fish. Broken water gives them cover, and these denizens will move to a fly. And after a hatch fades, sizeable trout can be found waiting under overhanging branches for cripples caught in the slow inshore currents. A sidearm cast back under the branches toward shore is the only way to entice these fish, if you can accomplish the nearly impossible trick of getting a drag-free drift coming from fast to slow water.

Fishing Rivers

Today, on the lower Yuba and the Truckee drainage, which I claim as my home rivers, I remember the lessons of Andy on Hat Creek, Hale on the Big Horn, and the Storjohans’ stretch of the Madison, and I fish the near-shore banks. On the lower Yuba, the winters of 2009 and 2010 were low-flow years with no catastrophic water events. I fish the river all year with dry flies, and even at these lower flows (800 to 1,200 cubic feet per second), inshore fish are often the first ones that you spot. These fish come to the bank because that’s where the first bugs of a midday winter hatch show up, and the pickings are easy in the slow current.

In January and February, for example, when the Skwala stoneflies start appearing, trout look for them first in the shallows, along the bank and tight to the willows. They aren’t pushovers, and often the best approach is to stay out of the water and make your first cast a good one. A bullin-a-china shop approach sends trout fleeing for their lives, just like when an osprey or eagle dips low over the water. Rarely will you get a second chance. If you don’t hook up and your fish moves, ease into the water carefully. That fish may just move out 5, 10, or 15 feet and take up another lie. You get another chance and may spot more fish above and below your entry point. Better yet, if you spot a fish up or downstream from your position, move to it and wait. Your fish will eventually show again, and you have another shot. If you rush into the water, you may see wakes heading for safer places. Sometimes I build small rock pylons on the shore to mark where I have spotted fish. No, they’re not prayer mounds. The fish will follow their underwater road maps back to those same positions day after day until the water level changes.

Late 2010 saw early normal low flows on the lower Yuba, but unseasonal heavy rain, snow, and runoff made reservoir managers dump water to maintain safe storage levels going into spring of 2011, and high water has made us change our tactics. Both wading anglers and those fishing from drift boats are finding fish exclusively on the edges and in the soft water inside seams. A year ago, the willows were behind wading anglers and obstacles to back casts. This year, the flows go up into the willows. So find a break and edge out carefully to where you can make a roll cast that will bring your flies and the indicator down and a few feet in front of your position. Fish don’t like swift, heavy water any more than you or I do. A hint or more of color in the water actually helps the fishing, because trout cherish the protection of lower visibility and move even closer to the bank. This spring will see high and late runoffs. Early season trout fishing is going to be on the edges, so polish up your “inside” techniques.

On the Little Truckee, I always counsel first-time anglers to try to fish this stream without entering the water, particularly during times of low water. More fish are frightened or put off the bite on this river than ever caught. A low profile and a long leader help, as does clothing in natural colors that match the riparian vegetation. You may not want to wear those chromed aviator sunglasses and red baseball cap. If you fish indicators, use a dry fly to suspend your WD-40 nymph or small Brassie. A small, pill-styled indicator works well here, too, as does a long leader with nothing more than a small nymph on the point.

I love to fish the Truckee itself below town on hot August and September days when grasshoppers are swarming in the streamside grass and a warm wind is howling down from the slopes of Donner Pass. It’s not the easiest time of the year to catch fish. It’s like doing twenty stations on an exercise trail at your local park. If I enter the water, it’s a gentle, quiet slide so my butt’s against the bank, giving me a low profile. I move from undercut bank to overhanging mulberry or willow for a mile or two. I’ve scouted these areas for years and know where there is cover and enough water depth to hold fish. I throw short, snub casts and feed a hopper down toward my target, often a fish that’s only six inches from shore. If nothing shows, I get up from my seat on the bank and move down a well-worn path to my next spot. This also isn’t a bad technique when the first snows fly and the October Caddis come out. Does it catch lots of fish? No, but my biggest browns, rainbows, and Lahontan cutthroats, since I moved to Tahoe 14 years ago, have come to the net this way.

Fishing Lakes: Trout

It’s not just rivers where you’ll find big fish in the shallow water close to shore, either. Some of the largest trout that I have ever hooked — hooked, not landed — were in an impoundment at a private flyfishing resort near Big Bend on the Pit River. It was cold and very windy. Waves came down the lake from the north, and open water was nearly untenable in a float tube. I found a sheltered shore south of a small point with protected banks and quieter water. I searched for a long time along the inshore edge of a shallow flat that held reeds, grass, and blown-down tree limbs.

It took a while to register, but finally I saw some reed movement that couldn’t have been caused by the wind or waves. Something was causing those stems to move back and forth. I sidearmed a cast toward the movement, let the weighted size 14 gray A.P. Nymph plop and settle for a two count and started my slow, short short-long retrieve.

The reeds exploded. Green algae flew through the air, and a trout that looked as big as a salmon grayhounded across the shallow flat toward the deep channel that ran down the lake. I lost it and two more fish in the next hour before darkness engulfed Frog Lake. Was I disappointed? Not on your life. I had hooked more big fish in an hour than I could remember and was reminded once again to look to shallow water for big fish. Last year, I found fish in the same area.

Stillwater guru Denny Rickards spends much of his angling time hunting in shallow water, particularly during the morning or during other periods of low light, such as when the skies are overcast. He knows that his best chance at a trophy fish comes on his first cast to undisturbed water. The chances of hooking up diminish considerably after that first slap of line, whether you’re fishing a lake or a stream.

I’ve fished with Denny a few times, and as with Andy, there’s no rush to the water. He studies a long while, looking for telltale signs in the wave patterns, prepares himself mentally, positions himself expertly, and fully expects to catch a fish on his first cast — and he often does.

Denny’s deliberate approach pays off when fishing from the bank, as well as from a boat. Last year, I fished Lake Davis with Norm Sauer, a fellow member of Gold Country Fly Fishermen and a superb stillwater angler. On the early morning drive from Nevada City, we reminded ourselves that our game plan for the day’s fishing was to start on the bank, whether at Camp Five, Jenkins Point, Cow Creek, or Mosquito Slough, wherever the weather, water temperatures, and angling reports suggested fish might be concentrated.

We parked our truck back from the shore, farther than an easy launch would dictate, and began looking for cruising fish as soon as we opened our doors. We had our rods rigged — our first casts sometimes are made in street shoes. After donning waders, we still hadn’t entered the water when we began to target fish tight to the bank. Later in the day, the fish can be keying on migrating damselflies and can become very selective, refusing fly patterns that don’t mimic the natural form, function, and color of the real deal, but in the dim light of early morning, when they venture into the shallows, they tend to be very opportunistic and hungry and will chomp on a number of foods. Mainstay fly patterns are Callibaetis nymphs and small midge pupae and emergers, but minnow streamers and the venerable Woolly Bugger work, too. We picked up two or three fish before we drove them out into deeper water. Then, when we finally moved into the water, we did so very carefully, picking a small point and gingerly working out several steps at a time, casting in a searching radius and sometimes back toward shore. We let the fish move toward us, patiently waiting, hoarding our casts lest we disturbed the placid surface too much and send our trout scurrying.

At Davis, our fish remained inshore well into the morning. Sadly, quality sight fishing of this type is often ruined by overexcited, unobservant anglers who rush up and trash the inshore water when launching their tubes, pontoons, or prams.

Bass, Too

Of course, bass love shallow water close to the lake’s shore, where they can hide and ambush their prey. A few years ago, prolific angling writer, speaker, and bass guru Ken Hanley was on the program ahead of me at a fly-fishing conclave. I sat down an hour early and took it all in. Ken’s presentation was about stealth and fishing from shore. He applied many of the same principles of approaching the water and fishing the shallow water first that I had learned while fishing for trout, including staying out of the water and making as little fuss as possible once in it. Bass have well-developed lateral lines that sense noise and vibration. Legendary guide Jay Fair tells of a local pond where bass regularly move from a favored end to the opposite shore whenever a heavy-footed angler arrives and wades in.

On a number of occasions when bass fishing, I have beached my boat and taken to foot to fish the near-shore water more effectively. Some of my best days have come when fishing this way. I have also used my boat to transport a float tube to my chosen destination on the lake. When float tubing, I keep my tube out farther from the shore than most because I am concerned about spooking my targets.

Like Denny Rickards, I think my best chance at a big fish comes on a long first cast before I have disturbed my fish. I do everything I can to set up for a great first shot, even taking a few practice casts outside to measure for distance and get my timing down, instead of making a hurried cast that ruins my chances for the evening in that spot. You rarely get a chance at bass over five pounds a second time.

If I’m successful, I release my fish, wait a minute or two, and try another cast to the same area, hoping for a mate. If it’s no go, I kick farther in to explore the nearshore water that produced my first bass. I probe with my fly rod to check water depths and debris. That knowledge will pay off on my next visit, maybe an hour later, when I am kicking home.

When bass fishing, I do everything I can to avoid spooking these wary fish. I avoid the commonly used short 5-foot or 6-foot bass fly leaders. Overlining your fly rod one line weight with an aggressive bass taper allows casting ease and accuracy with a 9-foot leader and a balanced bass popper. I don’t want my bug to turn over so rapidly that it crashes down and sends waves spreading. Bass may give away their position with a moving reed, a wake, or waving blades of grass. If you get close, are really still, and have good polarized sunglasses, you can see them moving back and forth.

Stop, Observe, and Look Inshore

Several times each week, my friend Norm and I touch base and arrange to meet on the river. While donning our waders, boots, and winter Gore-Tex shells at a huge rock that overlooks the river and offers a view up and down a fabulous stretch of water, we always remind ourselves of the lessons I’ve been recalling here: approach carefully, stop, and look inshore first. Observe intensely, approach with care — and don’t step on the fish.

When You First Reach the Water…

Stop before you enter the water and spend a few moments observing. Look for aquatic insects in the weeds and shrubs, hatching insects on the water or in the air, the rise forms of feeding, and the movement of fish subsurface. Remember: If you can see a fish, you’ll have an easier time catching it.

Note air temperature weather conditions, water clarity, and current speed. Are there clouds or fog that allow fish to feel secure when they are close to shore? Is the current so strong that fish prefer to hold in quieter water near the bank?

Look for birds such as swallows, flycatchers, nighthawks, herons, or egrets.

Their actions can provide a clue as to insect and prey-fish activity.

Let what you observe guide your approach and choice of line and rigging.

Start in close. Have a strategy for effectively covering the water. Place your first casts near shore, then move outward.

Trent Pridemore