It’s raining! It’s raining! The trouble is, it’s not raining rain — or at least not very much of it. It’s raining drought proposals, which that are pouring out of the state capital. At last count, state officials, lawmakers, nonprofit groups, and wildlife agencies have released six plans, including temporarily eliminating some fishing and creating a high-level task force to deal with the effects of the four-year drought.

In case you’ve been fishing in Outer Mongolia and missed the drought news, here is the official word on it from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: “The current conditions are the product of several poor wet seasons in succession. The past 30 months — encompassing the past two winter wet seasons and the first half of the current one — are the driest since 1895 for comparable months.”

Signs of drought conditions can be seen in California’s mountains and trout rich lakes and streams. State water officials report the Sierra Nevada’s snowpack, which would normally provide runoff into the summer, is the lowest ever recorded. Many north-state reservoirs are so low that they look like moonscapes. Portions of some trout rivers have stopped flowing, in some cases stranding trout to suffocate in tepid pools.

Drought conditions prompted Governor Jerry Brown to issue an April 2015, executive order declaring that “a State of Emergency exists in the State of California due to the ongoing drought . . . the severe drought conditions continue to present urgent challenges, including degraded habitat for many fish and wildlife species, increased wildfire risk, and the threat of saltwater contamination to fresh water supplies in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta.”

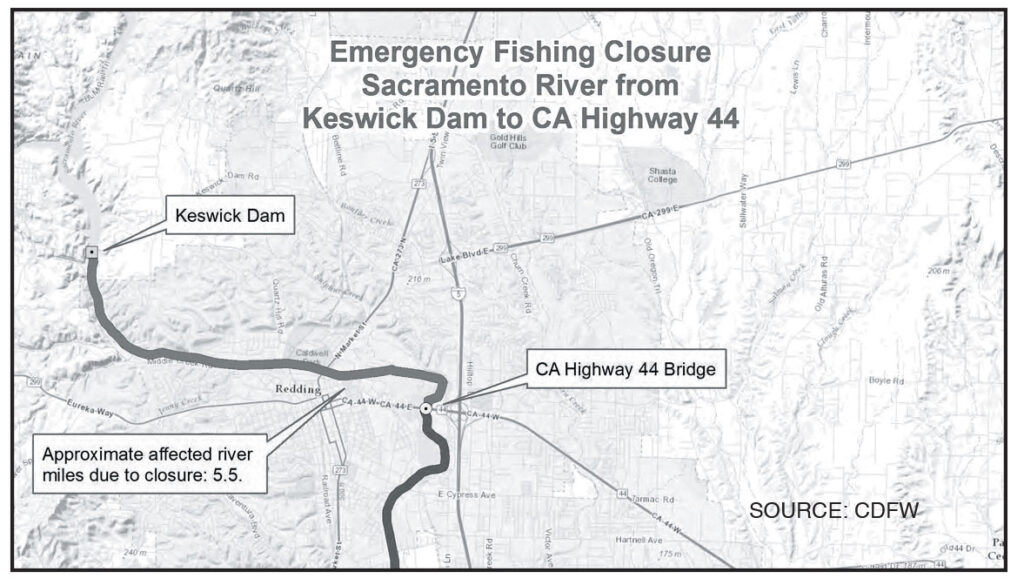

That order, in turn, prompted the California Fish and Game Commission to take emergency action to protect endangered chinook salmon on a popular stretch of the Sacramento River. To protect endangered spawning winter-run chinooks, on April 17, 2015, the commission approved a change in regulations closing all fishing along a 5.5-mile stretch of the Sacramento from 650 feet below Keswick Dam to the Highway 44 bridge from May 1, 2015, through July 31, 2015. The closure includes the Sacramento River tributaries of Antelope, Deer, and Mill Creeks and the Russian, Shasta, and Scott Rivers. Normal fishing resumes August 1, 2015. The action is designed to protect an area that is critical for spawning chinooks, which have been listed as endangered under the California and federal Endangered Species Acts. The 20.3 miles of river downstream from the Highway 44 bridge to the Deschutes Road bridge will remain open to fishing using only barbless hooks and with a bag limit of two hatchery trout or hatchery steelhead, with possession limited to four.

There are 17 distinct runs of the chinook salmon, four of them using the Sacramento–San Joaquin River system. Chinooks are the largest of the Pacific salmon and can grow to nearly five feet long and weigh up to 129 pounds, although a more typical length and weight is three feet and 30 pounds. They are born in streams, and after reaching the smolt stage in a year or so, swim to the ocean, spend a few years there, then return to their natal stream to spawn and die.

“Maximizing adult spawning numbers is critical to the population,” said Sonke Mastrup, executive director of the commission, in a memo justifying the emergency closure. “A fishing closure in the holding and spawning areas of winter-run chinook salmon will add to protections to the federal and state endangered fish facing a high risk of extinction.” During the public hearing before the commission action, several individuals proposed that the policy be changed to reduce the length of the closure area by 1.2 miles and that angling be limited to catch and release and the use of a single barbless hook on an artificial fly. These proposals were rejected.

The proposed action drew support from a well-known conservation activist and fly angler: “I fished that area in Redding, and I understand the position of those who advocate for less than a closure,” said Sacramento’s Charles Bucaria, who has been actively working to protect salmon in the American River. “These areas are so critical and the water is so much lower than when I fished the river that we have no alternatives, and a temporary closure needs to take place. The reality is even with that, we have no control over the late summer temperatures, and we may well have further problems. I suspect that in the American River, we are going to have hard-boiled salmon and steelhead late in the season. I am in favor of the department’s proposal.”

The Sacramento and its watershed rivers are very popular with fly anglers, partially because of the easy shoreline access to fish and launch boats. While salmon are in the river, they don’t often hit a fly, but are sometimes snagged and quickly broken off by anglers.

“Because of the extreme circumstances, this portion [of the Sacramento river] is basically going to be reserved for fish,” said Harry Morse, a California Department of Fish and Wildlife public information officer from Redding, who added that almost all of the winter-run chinook salmon spawn in that stretch of river. In 2014, 95 percent of the eggs and young of winter-run salmon died because the water was too warm, Morse told the Redding Record Searchlight: “Biologists expect conditions this summer to mimic the previous spawning season and want to reduce the stress on the salmon, which may be accidentally caught by anglers trying to hook trout or other fish,” Morse said.

As part of its drought package, the DFW recommended that landowners and agencies sign agreements to keep water in creeks and rivers during the drought to prevent a repeat of big fish kills that have previously occurred. Sierra Pacific Industries (SPI), a timber company and the largest private landowner in California, was among the first to take part by entering into an agreement with the agencies. “This is one of the toughest water years in recent memory for people, cattle, and fish,” said Archie “Red” Emmerson, owner of SPI. “ We have learned a great deal about salmon spawning and rearing on our properties. This year, we are volunteering to keep additional cold water in the creeks to help salmon. We hope working with the fish agencies will give the salmon a better chance to survive this difficult drought.”

Governor Brown’s order recommends 31 actions, because he says “the distinct possibility exists that the current drought will stretch into the fifth straight year in 2016 and beyond.” The following fish-saving actions are either underway or in the planning stages by DFW and water-management-agency officials:

- Expanding the trucking of approximately 30 million salmon smolts from some state and federal hatcheries to key areas in rivers.

- Increasing the capacity of the Livingston Stone National Fish Hatchery at Shasta Lake to raise chinook salmon.

- Conducting rescues to save f ish stranded in pools caused by rapidly dropping water levels in rivers and streams.

- Playing an active role in the governor’s Drought Task Force, whose members are state agency heads who have been holding drought information-gathering hearings around the state.

- Giving some DFW hatcheries a conservation orientation, which means operations will be oriented toward fish rescues, rather than toward raising fish for the state’s traditional hatchery purposes.

One of the actions includes the use of the governor’s emergency powers to mandate that California’s towns and cities cut water use by 25 percent, compared with 2013 levels. The urban focus for the water reductions drew immediate criticism from environmentalists and wildlife conservation groups for not including agricultural users. California farmers use 80 percent of the state’s water while contributing less than 2 percent to the state’s economy.

On a national television interview program, Governor Brown said that some farms already had been denied irrigation water that is critical to providing fruits and vegetables not only to California, but also to the United States as a whole and to a significant part of the world. Environmentalists countered that the state’s water is so oversubscribed that any cutback would be impossible to monitor or enforce. Water managers are restricted by somewhat arcane policies and permits that give priority to those who obtained appropriative rights to water before 1914, rights that remain in effect as long as the holder uses the water for beneficial purposes. This is generally known as the “first in time, first in right” claim to water. Post-1914 rights are more subject to reallocation and to drought limits imposed by the State Water Board. (For more information on the water rights process, see http://www.waterboards.ca.gov/waterrights/board_info/water_rights_process.shtml#law). In a carefully worded statement, the governor said he would review the historical water rights arrangements.

The governor got a first-hand look at the effects of the drought when tagging along on an April 1, 2015, snowpack survey that showed the lowest measurement ever recorded — just 5 percent of average for the date, the lowest in 65 years of record keeping. Last year’s snowpack on the same date was 25 percent of average, an all-time record low until the new record was set this year.

The U.S. Drought Monitor reports that as of March 31, 2015, 94 percent of California was in severe drought. The most visible effect of the drought is the low level of the state’s reservoirs. As of April 2, 2015, according to state water officials, Shasta Reservoir was at 59 percent capacity, compared with the historical average of 73 percent for the same date; Trinity Lake was at 49 percent, compared with 62 percent; Lake Oroville was at 51 percent, compared with 66 percent; and Folsom Lake was at 58 percent, compared with 90 percent. Water officials say that the reservoirs contain enough water for residential, commercial, agricultural, and fish-and-wildlife use if conservation measures are successfully implemented.

In March 2015, a senior water scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech wrote a guest editorial in the Los Angeles Times saying that California has a very limited supply of water in its reservoirs because of the drought and overuse of water in the past decade. “Right now the state has only about one year of water supply left in its reservoirs, and our backup supply, groundwater, is rapidly disappearing,” wrote NASA’s Jay Famiglietti in the March 13, 2015, editorial. “California has no contingency plan for a persistent drought like this one (let alone a 20-plus-year mega-drought), except, apparently, staying in emergency mode and praying for rain.” In the piece, Famiglietti, who is also a professor of Earth system science at UC-Irvine, gave these recommendations for dealing with the drought:

“First, immediate mandatory water rationing should be authorized across all of the state’s water sectors, from domestic and municipal through agricultural and industrial.

“Second, the implementation of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act of 2014 should be accelerated. The law requires the formation of numerous regional groundwater sustainability agencies by 2017. Then each agency must adopt a plan by 2022 and ‘achieve sustainability’ 20 years after that. At that pace, it will be nearly 30 years before we even know what is working. By then, there may be no groundwater to sustain.

“Third, the state needs a task force of thought leaders that starts, right now, brainstorming to lay out the groundwork for long-term water management strategies. Although several state task forces have been formed in response to the drought, none is focused on solving the long-term needs of a drought-prone, perennially water-stressed California.”

On December 13, 2013, the governor created the Drought Task Force, which consists of heads of agencies and has been holding hearings around the state. The group has been assessing regions of the state most affected by the drought and clearing the way for transferring and trucking water and eliminating barriers to helping agencies in cities and counties.

At the State Capitol, the state legislature passed and the governor signed into law Assembly Bill 91, which earmarks $1 billion in funds for drought-related projects, including making it easier for the DFW to spend existing voter-approved bond funds for such projects as fish rescues, increased hatchery production, and habitat improvements. In addition, AB92 authorizes increased state regulation of water-guzzling and stream-diverting marijuana growing operations.

The governor also signed a companion bill, Assembly Bill 92, which authorizes fines up to $8,000 for illegal diversions of water that is needed to safeguard fish. Republicans opposed AB-92 for giving too much power to state officials. Assembly Minority Leader Kristen Olsen, R-Modesto, said the legislature should focus on speeding up construction of new dams and reservoir projects in the drought measures. As part of the state budget, the governor added $8 million to the DFW to pay for work to protect salmon.