The striped bass is one of the most valued and most pursued fly-rod game fish in the continental United States. For decades, stripers have been targeted from coast to coast and throughout the inland states, in salt water and fresh, in lakes and rivers. Since the early 1990s, fly fishing for striped bass in the California Delta has grown from the passion of just a handful of fly anglers to the avocation of several hundred. When I first started chasing Delta stripers, there were no fly-fishing guides. Today, there are more than a dozen fully licensed guides steering hopeful anglers into slugfests with Morone saxatilis — some pretty damned good ones, too. I was a licensed Coast Guard captain and guided on the Delta myself for nearly two decades. It was especially gratifying to get a newbie into his or her first striper on a fly. I’m retired from guiding now and enjoying the fishery more than ever, fishing alone or with valued friends.

I rate our California striped bass as one of the most valuable game fish in the state. They provide not only superb recreational angling opportunities for bait fishers to fly anglers, 12 months a year, but an economic boon as well, because this remarkable fishery generates millions of dollars annually. Fortunately, California’s legally introduced striped bass were designated a game fish with all protections in 1935, although there have been attempts by Central Valley agricultural business interests to remove protections from our stripers. I’m not going to get into that in this article. We defeated those attempts, but constant vigilance is required to maintain game fish status and protection for our stripers.

Although our striper fishery offers year-round angling, with September, October, and November being the peak months on the Delta and with numbers of quality fish in the area as early as August, the winter — December through March — the least-fished period of the year, can often provide exceptional fly fishing for Delta striped bass with minimal competition, particularly during drought or low-water years.

Typical Winters

I consider late December as the official kickoff of winter striper fishing most years, depending upon the severity of the weather. It takes quite a lot of rain and runoff to turn the entire thousand-plus miles of Delta waterways the color of wet cardboard. Accordingly, fishing success can be quite good throughout the Delta during early December, especially if the water temperature stays at 50 degrees or higher. Once the water turns turbid and runs high and cold, you’ll have to find clearer, warmer water, and that means looking for dead-end sloughs where the tidal circulation of water is reduced. Checking a chart to find those sloughs is the easiest way to locate them, to see where the closest launch ramps are, and so on. However, some of the best of those sloughs have been dramatically changed by invasive weed growth over the years, the upper ends (the cleanest water) plugged by densely packed vegetation. Still, there remain a number of fishable areas with open water that will hold stripers, once the water quality sours in the usual places that we target during the spring, late summer, and fall months.

There is a resident population of stripers year-round in the Delta, from dinks, as we call sublegal fish (those under 18 inches in size), to whopper 50-pounders. Most of the adult fish, however, outmigrate back to the ocean and the lower San Francisco Bay system after spawning in late May and June, returning again to winter over in the vast Delta system beginning in September and sometimes as early as August. The run builds all fall and winter, although there is a run of fresh fish in March, most years. These have wintered over in the bay system, rather than in the Delta, as the majority of fish do.

Our striper population is at its all time low, under a million adult fish, but most of those will be in the Delta during the winter months, and they can be caught with the right flies and lines, if you can find them and use the correct approach. If you are brand new to the striper game and wish to target winter Delta stripers, I strongly advise you book one of the many good guides who continue to serve Delta fly anglers during winter. Fly shops in the Sacramento and San Francisco Bay areas can recommend guides, and I also have a list on my Web site’s Coast-to-Coast Guides page: www.danblanton.com/blog/category/fly-fishing-guides/california-bay-delta/.

Top Flies and How to Fish Them

There are lots of productive styles of flies that work well on Delta stripers, fall, winter, and spring. I think I’m safe in saying that some version of my Flashtail Clouser (called Blanton’s Flashtail Minnow by Umpqua) is the most popular among Delta striper devotees. Most are tied on 2/0 to 3/0 jig hooks, with barbell eyes ranging from 7/32 of an inch to 1/4 of an inch. I prefer 1/4-inchers for most of the season and especially in the winter, when I want the fly to push more water and get down faster. Many top Delta fly anglers, such as Captain Mike Costello, prefer to build a rattle into their Flashtail Clousers. This makes perfect sense when the water is turbid.

When water temperature drops below 50, turbid or clear, I often find my Flashtail Whistler produces best, since it pushes more water, sending out water wakes that the bass can feel and home in on, even in the murkiest soup. The difference can be profound at times. When the metabolisms of the fish have slowed down as the water temperatures plummet, they don’t need to feed as often, but when they do, they like a mouthful. That is why I fish larger, longer and bulkier flies during the winter and early spring, when the water is at its coldest. If the water is turbid, darker patterns that push more water score best for me. That’s when I’ve found my Big Eye Flashtail Whistler to be one of the best producers.

Top colors ranges from bright to dark — white and chartreuse with a blue top, black and chartreuse, and other variations from light to dark. If the water is clear, I tend to favor the brighter colors — and so do the fish.

Once the water temperature drops below the 50-degree mark and the metabolisms of the fish slow down, you’ll have to adjust your retrieve to accommodate the sluggishness of the stripers. Use larger flies and retrieves with longer, slower pulls, incorporating lots of “stop-and-drops,” as we say — sometimes a pause and drop lasting five seconds or more. The fish often eat on the drop or on the first pull after that fall, so keep the rod pointing directly at the fly, rod tip touching the water’s surface. Reducing slack in the line is of paramount importance. If you lose contact or don’t feel the drag of the fly, set the hook. Winter fish often just swim up to the fly, inhale it, and then don’t veer off, the way summer and fall fish do. Retrieving the fly until the leader hits the rod tip and then letting it hover at the surface momentarily is mandatory if you don’t want to miss opportunities — stripers will follow the fly right to the boat. I prefer the “scissors” strike set, over the strip strike — a hard pull with the line hand while swinging the rod low to one side. You need to move the fly some distance when the take is soft, and often there is some slack in the line. The eats can often be as subtle as that of a trout sipping a nymph.

Time and Tides

Nothing is etched in granite, but I’ve found than in the dead of winter, when the water temperature drops below 48 degrees, there is no need to be on the water at first light. I’ve come to the conclusion that the bite may not even start until late morning or even early afternoon, when the water has had time to warm up a bit. I check the tides and love it when the start of the outgoing tide is around 9:00 a.m. By the time I’m on the water and hit my first stop, the fish have usually begun to feed.

While fishing can be torrid on any tide, I personally prefer outgoing tides, since they draw baitfish out of the weeds, making them more accessible to hungry bass working the weed edges. I try to time my departure from the dock at the start of the outgoing tide, if I can. The moon phase doesn’t make too much difference, but I try to avoid a full moon. I like it best when there are two tidal runs a day — a high and falling morning tide, a low at noon, and an incoming tide the rest of the day.

Structure

Productive structure for winter fish is not that much different from the feeding or holding structure that they prefer at any other time of the year, with a few exceptions, even when fishing the upper ends of deadend sloughs. The fish will be found wherever a concentration of baitfish is found, especially around island points, rocky, weedy banks, and in transition zones where shallow water meets deeper water or where tule banks change to rock banks. Such transitions are high-percentage spots. I especially like working the mouth of a pocket in the tules with a weed edge running across the front of it. As the tide drops, baitfish hiding safely back in the pocket will have to move to the outer edge with the falling water. Stripers know this and will be lurking there. Any drainage or outflow will hold ambushing stripers on the downcurrent side of the drain.

Feeding winter stripers can be found at all water depths, from shallow and moderate to deep, but I’ve found that often the best results can come from water only three or four feet deep, especially water with a weed edge or tule bank. Water warms up sooner in the shallows, warm water attracts baitfish, and the bait beckons the stripers. They can be large ones, too. Big fish have no aversion to shallow water any time of the year, but they especially like it during cold winter months. That said, when they are not actively feeding, they can be resting at deeper depths, especially at transitions. Again, I don’t head out too early, and I look for shallow water on a falling tide.

Extreme cold fronts, which drop the water temperature to almost freezing, can kill baitfish such as threadfin shad, a primary forage fish for Delta stripers and largemouth bass. I don’t like prolonged periods of freezing weather, because it kills massive amounts of bait, driving the survivors to deep water — water deeper than 30 feet. During that time, find protected, slow-moving water, deep water, and you’ll find baitfish and stripers. Harbors, turning basins for ships, and even residential waterfront communities such as Discovery Bay are great places to target when ice forms in the guides. You’ll likely have to fish deep, though, and a fast-sinking line will be needed.

Tackle and Other Equipment

The most popular fly rods used for Delta stripers are fairly fast, strong 8-weights — sometimes 9-weights when tossing heavier, bulkier flies. Examples of good sticks abound — it’s easy hard to find a really good fly rod at most price points these days.

For winter fishing, I always have two rods rigged, one with an integrated shooting head for deep-water work (28 feet of T-14 tungsten head for both 8-weights and 9-weights) and the other a rod lined with an intermediate line for shallow-water presentations. I sometimes rig a stick with an intermediate line with a 30-foot Type 3 sinking head, which also works very well in shallow water, but not as well as the regular intermediate, if a slow retrieve with long pauses is required. Top-water action when the water is below 50 degrees is rarely an option, so I don’t bother with a floating line during the dead of winter.

A line management device or “stripping tub” is an essential fly-fishing tool when casting from a boat, in my experience. Today, when you see someone on the Delta fly casting without a stripping tub, you know they are a stubborn holdout or are new to the game. I won’t go into benefits here, but once you use one, you’ll never go back to stripping your line onto the deck. There are many good tubs on the market, and some anglers make their own.

I like to keep it simple when it comes to leaders. For superfast-sinking T-14 type lines, I prefer a straight length of 20-pound mono 8 feet long. I tie a three-turn Surgeon’s Loop in one end, which loops to the loop on my fly line, and I attach the fly with a loop knot, the Harro Knot being my favorite. For intermediate lines (and floaters, too), I like a 5-foot furled-type leader made with 20-pound mono and with a 50-pound swivel on the tippet end. Using the Harro Loop Knot, I attach a 2-foot length of 20-pound mono to the swivel as my class tippet. The swivel makes for easy tippet attachment and easy fly changing. It also prevents line twist.

Boats and Other Watercraft

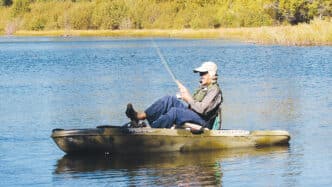

The Delta is a big place, and to cover it effectively, you need a boat. Craft can range from car toppers to 18-to-20footers, from center consoles (CCs) to walk-throughs and bass boats. I love my 18-foot Eagle CC, but a nice walk-through style with a protective windshield sure is nice when running in cold weather.

Prams, float tubes, and kick boats can be used on the Delta, but you’ll need to fish protected water, preferably in a slow-speed zone for boats. The five-mile-per-hour zones in the sloughs around Bethel Island are examples of places you can fish from these small personal watercraft. Always wear a bright personal floatation device. This goes for those fishing from larger boats, as well.

Take Advantage of Drought Winters

Drought years are horrid, and we never should wish for a rainless winter, but they come now and then, and when they do, why not take advantage of them? When they shut down the coastal steelhead and salmon rivers due to low water, the Delta remains open, with good water conditions. There is little or no turbid water, and the fish continue to be present throughout their normal fall range. Take this past dry winter for example: the fishing throughout the Delta from late December through the dead of winter was as good as it gets — even better than the fall season, because there were more and larger fish in the system. I and others enjoyed many big-number and big-fish days in late December, January, and February — on into the spring.

Of course, every season will bring changes, especially in structure. Each year, I find myself learning the Delta all over again. One high-percentage spot is lost for some reason, but another always is found. Don’t hesitate to explore, to look for new “right” winter water.

So if your favorite winter steelhead water is blown out — or shut down for low flows — consider a trip for striped bass on the California Delta. Hire a guide, if don’t wish to explore on your own. The Delta is a treasure of immeasurable value for lots of reasons, but striped bass top the list. I can almost guarantee that after one successful outing on the Delta, like me, you’ll be hooked for life.