Early in my fly-fishing life, I learned about a deadly method for catching fish. Actually, it was the fly, as much as method. And I started catching fish, a bunch of them. Then, for reasons explained below, I slowly stopped using this fly and technique and stopped catching as many fish.

After many years — decades, is more accurate — I reaffirmed something about the best part of fishing. At least for me, that is the part where you actually catch fish. Every so often I would hit a dry spell — like for three years — and I realized I could do better. So I revisited the method I had used when I was knocking them dead on any water I fished, which involves using this killer fly. And my latest findings confirm what I learned decades ago.

It all started in the early 1980s, when I got my hands on probably the best book ever written on how to catch more and bigger trout. This was a topic of high interest to me during years when a 14-incher taken in the streams of the central Sierra, primarily the North Fork of the Stanislaus near where I had a cabin, was the best catch of the year. Not surprisingly, the book’s title is Larger Trout for the Western Fly Fisherman, by Charles E. Brooks, a 1970 publication that was republished in 1983. It’s out of print, but used copies are still available in places.

Here’s the secret. The best fly for consistently catching more and bigger fish in most streams and rivers is — the Woolly Worm. And as another fly fisher and writer whom I’ll introduce later attests, this pattern might also be the best fly for still waters, as well.

As Brooks writes, the Woolly Worm is a fly with a long history. Over five hundred years ago, it was used in England, where it was variously called the Palmer, Soldier Fly, Pilgrim, Army Worm, and Black Hackle. It was in use there a hundred years before Izaak Walton wrote The Complete Angler. And it has always worked. Brooks estimates “this one pattern accounts for more worthwhile trout in the Rocky Mountain West than any six other patterns.”

Brooks spent time in California after World War II as a ranger in Yosemite National Park and got started fly fishing on the Merced and Yuba Rivers. But it was when he retired to Montana in the early 1960s that he really learned how to hook big fish consistently.

He made his greatest discoveries while underwater. In 1961, while gathering coins on the bottom of swimming pools for some local kids, he surmised that this might be a good way to study trout behavior and to try to figure out why they sometimes take a fly and more often don’t. So with a plastic face mask, he went to one of his favorite rivers, lowered himself underwater in his jeans (no neoprene wet suit for him), and began his studies. Much of the time, his wife drifted a fly down to where he and nearby trout held. What follows are his discoveries.

After he settled into position, Brooks was surprised to see that fish ignored him as long as he did not make any quick movements. His first revelation came when he saw how a wet fly behaved underwater. As it drifted, the currents above “plucked and pulled at the leader, turning and twisting it, and the fly followed along, willy-nilly, showing its back, belly, and all sides.” All wet flies behaved this way, except if they had unflattened bodies. Since real, live insects don’t twist and turn in the water as they get swept down, this unnatural behavior spooked the fish.

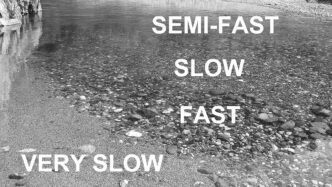

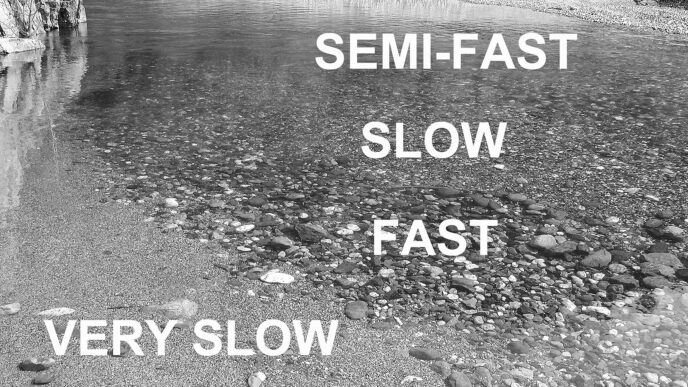

So, score one for the Woolly Worm — it always looks the same from any angle. It appears to be in control of its actions. It appears to be alive. The fish see it as a real food. Brooks also noticed that when the fly and current moved at the same speed, the Woolly Worm “bloomed” — its fur and hackle flared out and looked very lifelike. When the fly moved faster than the current, its components were compressed and didn’t seem lifelike. When the fly moved more slowly than the current, the fly again appeared to be unnatural.

Brooks noted that whenever any object, whether stick, leaf, insect, or whatever, appeared within the trouts’ vision, the fish showed interest until they saw it was not edible. When the artificial fly appeared, it quickly got the trouts’ attention, but if it was twisting and turning or behaving in an unnatural manner, the fish would inspect it, sometimes follow it, but almost always reject it. When the fly acted naturally, the fish would usually take it. If the fly made an unnatural movement at the last minute, the trout would swerve wildly away and remain wary. This was especially the case if the fly was picked up while it and the leader were still in vicinity of the fish. This put the trout down for a considerable time. He found that weighted flies drift more naturally and of course deeper, which is significant because Brooks found that trout in their holds seldom look up. The trout ignored anything drifting more than a few inches above its head. (The exception to this, of course, occurred when there was a hatch that brought the fish to the surface.) He also found that fly size matters. The larger fish clearly preferred larger flies, somewhere in the middle range between sizes 10 to 12 and 2 to 2/0. The most effective color was a dark one, with black being tops. Other colors, particularly two-toned, were harder for Brooks to see and, he assumed, harder for the trout to see, as well.

He noted many cases in which a trout held a position and seemed content to stay there. It would ignore a drifted fly, except if it came within inches of where the fish lay — in other words, almost right before its nose. Then it would move, however, slightly and engulf the fly.

The Brooks Approach

Brooks’s underwater studies confirmed his long-held belief that “the most important thing in wet fly fishing is to cover the hold thoroughly,” and that belief determined his approach to fishing wet flies such as the Woolly Worm. One must employ several casts through the same exact area, he insisted, to ensure that the trout sees at least one natural drift of the fly close to where it lies.

He further emphasized: “It is imperative that the wet fly fisherman get his fly down to the bottom of the stream if he wishes to make consistent catches of good trout. Keep the fly on the bottom. If you do not feel it touch bottom now and then you are not fishing deep enough!”

Brooks normally used a two-fly setup, with a large, bulky fly as an attractor pattern and the target fly as the dropper.

His priority always was to find good holding water — “heavy water,” where the biggest fish usually hang out. Then he would commence his “assault,” first by casting repeatedly from the shore. After covering this near water thoroughly, he would wade out and make at least three casts and drifts. Then he would lengthen his line and do it again, about one foot farther out and one foot farther upstream, always trying to keep his casts short. He did this from however many places he needed to cover the entire stretch of water systematically. This was his first of four methods he used to fish the run.

If this first series of drifts didn’t produce, he would do hand retrieves for 5 to 10 feet after the fly reached the end of its drift (method two). If he still got no results, he would lift and dip the rod tip throughout the drift (method three). Finally, he would strip in the fly during the drift, pulling the line six inches or so (method four). The first method caught more fish than these latter three combined. Brooks reported that he did not change flies or stretches of water until he gave both the fly he was fishing and the water a thorough try with these different methods of presentation. He did not consider a hundred casts over a stretch of water 25 by 50 feet in size to be excessive for one method of presentation. Using four different methods of presentation resulted in hundreds of casts before he was willing to change flies or move on. If he knew that the water contained fish, he preferred to stay put, rather than searching for feeding trout in other stretches.

The main point of all of this is that if you are fishing a run where you know there are trout, it’s a matter of drifting the fly naturally down to where a fish holds. If you cover all the holding spots in this manner while not putting the fish down with an abrupt lifting of the fly, chances are very good that you will hook not only fish, but perhaps the biggest trout in this piece of water.

Applying the Brooks Approach

I read Larger Trout for the Western Fly Fisherman with a keen eye, and I embraced Brooks’s methods, although not the total package — especially the part about making hundreds of casts in the same pool. (I don’t possess that kind of patience and perseverance when fly fishing.) Except for this part, the Brooks approach most resembles the way I used to catch trout with night crawlers. I would put on split shot and sink the glob down under small waterfalls and rocks, particularly at the heads of pools. It’s an absolutely deadly way to take trout. (Later, I saw how these methods resemble the Ted Fay approach of using two weighted flies and a short line and placing them down in swirling pockets where trout sit, waiting for food.)

Armed with this new-found knowledge gleaned from Brooks’ book, I hit my favorite waters. I employed his two-fly approach with a slight variation. Instead of one attractor pattern, I used two Woolly Worms, often a yellow one and black one. I particularly remember a weekend trip with a friend to the East Fork of the Walker River. What really sold me on this method happened when I fished a run of straight, fairly shallow water in the Nevada section. I crept to the low bank and lowered the flies just over it, letting them slowly drift alongside it. Surprisingly, I caught three browns that barely struck the fly — they just engulfed it, the way they would a worm. The technique was even more successful in pocket water. In the meantime, my companion cast his fly out to sections of water where it stayed mainly on or near the surface. By the end of the weekend, I had caught 19 trout, he 3. I knew I had found a successful fly-fishing method to catch trout.

This kind of success followed on the upper Sacramento, where the two-Woolly-Worm method took fish after fish wherever I sank them. On the North Fork of the Stanislaus, where smallish rainbows predominated, I caught larger fish holding under the rocks where I used to catch them with night crawlers. In the Little Mokelumne on one outing, I brought up two 14-inch specimens, one a rainbow, the second a brown, by plying the deeper water with a Woolly Worm.

Then I discovered the Tuolumne, which became my favorite place both to camp and to fish. Its waters are big, and they typically required longer casts. To cover the water, I gradually switched over to surface patterns and loved it when a trout hit a dry fly on a distant cast. I found few things more enjoyable than having trout strike a grasshopper pattern cast to the other side of the pool. And in enjoying these long casts and hookups, I used the two-fly Woolly Worm method less and less.

After moving to a home overlooking the lower Sacramento, I again altered my fishing techniques. The food of choice of these wild rainbows is nymphs, so I have been fishing with small nymphs, just as most other fly fishers do there. The standard approach is a two-nymph setup under an indicator, mainly fished from a drift boat — the best way to access much of this river. My preferred method is to cast a single nymph out into the current from shore (I rarely fish from a boat) and allow it to swing down to where fish are feeding. I probably catch fewer fish this way, but my single-nymph approach is tidier and just more fun, with strikes that are often fierce, it does require that fish be feeding on or near the surface, however, which fits my routine of fishing primarily in the evening. But when fishing other waters, such as the upper Sacramento or East Walker, I stopped catching many fish across several outings, often getting skunked. In fact, I was experiencing basically mediocre fishing year after year, even carrying over to the lower Sac, where caddis hatches clearly have declined in recent years. (Some say this is due to the device placed at Shasta Dam in 1997 that delivers consistently colder water down the river for the benefit of salmon.) I concluded more than once that I was in a slump.

I then recalled those days when I caught a lot of fish by using Brooks’s methods, and I began once again using a weighted Woolly Worm to see if the magic was still there. I am reporting here that it is — these methods and this fly remain among the most effective ways to catch trout. Who cares whether the Woolly Worm resembles a stonefly, or large nymph, or caterpillar, or another terrestrial, or even a small minnow. Trout hit it.

This is true on just about any kind of water, including on the lower Sac, especially when trout are feeding on stonefly nymphs. When I can’t bring a trout to the surface of a deep run to grab my nymph, I sometimes switch to a Woolly Worm, perhaps place on several shot, or not, and fish through the run. In the last couple of years, I’ve enjoyed some great hookups this way.

Here’s the very latest report. While writing this article, a companion and I fished the tailout of a long, glassy stretch of shallow water where the fish come to feed on nymphs in the evening. On this particular evening, the trout fish were actively feeding, but on what? I hooked one early on a caddis emerger pattern; my companion got one at the very end of the session on a small black nymph. But for the hour between these two hookups, we got nothing, while the trout were feeding right in front of us. He wondered whether they were feeding on small yellow stoneflies or black caddis pupae. Whatever was the case, they proved very tough to catch. I went back the next evening. The river had come up, and that stretch seemed quiet. I put on a size 12 black Woolly Worm and fished some deeper sections with it. I just cast the fly with no added weight and let the current take it. In 30 minutes, I had hooked four rainbows, including a 17-incher. The Woolly Worm catches fish.

What’s surprising is that this pattern has dropped precipitously in popularity. Perhaps it is too simple to tie or doesn’t look precisely like anything. I recently visited one of the largest fly shops in the state; their displays have hundreds of compartments holding thousands and thousands of flies, and I couldn’t locate one Woolly Worm. I inquired of a salesperson, and he said of course they stock them. But when he went to the place where they usually were, the compartment was empty, and not from being sold out. The shop had just stopped tying or ordering them.

Stillwater Fishing

As I said, Woolly Worms are also effective stillwater flies. Advanced Lake Fly Fishing: The Skillful Tuber, by Sacramento resident Robert Alley (Frank Amato, 1991), is the best book I’ve read on fishing from a float tube, and surprise, surprise, Alley’s “perfect” fly for taking trout in such waters is the Woolly Worm.

He writes: “The fly [the Woolly Worm] works for any fish species and can be used in any situation imaginable by fishermen. It is, for these reasons, my favorite fly for exploring new lakes or streams because it can imitate a large variety of insects, bugs, crustaceans, and fish life.”

Alley fishes still waters throughout California and Arizona. He writes that he finds feeding fish mainly on the bottom or cruising in the shallows, seldom in the middle layers of the lake. So he employs a full sinking line that keeps his fly deeper, longer. He practices long, slow retrieves that keep his fly on the bottom. He likes to feel the Woolly Worm crawling over rocks, stumps, weeds, or smooth bottoms. If he finds weed beds, he fishes the fly just above them. Only if this fails to produce a fish does he fish levels between the bottom and the surface.

His standard technique is to execute slow, three-inch strips in a measured retrieve that simulates the natural swimming action of nymphs and crustaceans. Toward the end of a retrieve, he sometimes lets the fly and line sink back toward the bottom before beginning a new retrieve. (He uses longer and faster pulls with bucktails and streamers.) Since he knows that aquatic insects seldom swim in only one direction, he continually alters the direction of his rod tip during a retrieve to create a more realistic swimming action.

He found that flies “thinly dressed with only a whisper of a hackle” work best, not ones overdressed. Such a sparsely hackled fly not only catches the most fish, but also consistently the largest. His most successful fly for trout hookups is a size 12 Woolly Worm. He uses varied colors of patterns — brown, yellow-brown, yellow, bright yellow, green, two-toned — as well as black.

With my renewed desire to catch more fish, I started using Woolly Worm patterns more often when fishing lakes, and I confirmed much of what Alley has presented in his book — a Woolly Worm fished close to the bottom, with slow retrieves, is very effective. Even when “trolled” from a float tube, it takes fish. Particularly effective has been a two-fly setup, with a small Woolly Worm (size 14) attached by a 2-foot leader to the hook of a larger one (size 12 or 10). Trout may be attracted to the larger fly, but then take the smaller one. The Woolly Worm has worked on the selective wild trout in Manzanita Lake and on the sometimes equally selective hatchery trout that haven’t yet learned they’re supposed to eat insects.

What I conclude from all this is pretty straightforward. There’s nothing very wrong about using the flies and methods that local lore says work best for fishing a particular water, or those in which you feel the most confidence, or those that you enjoy the most. I do just that in fishing the lower Sac, by swinging small nymphs as discussed above. But if you want to improve your catch rate, or avoid getting skunked, or perhaps catch the bigger fish that won’t rise from their lairs, then don’t hesitate to put on a Woolly Worm and run it deep, whether in a river or lake. It just might be the ticket out of a fishing slump.