Rivers are always telling a tale. Sometimes it is a long-winded yarn, and you can make out parts of the story, but only after years of listening do you understand. At other times, the tale is a one-word bark that commands attention and, if you are fishing, demands immediate action. Few people speak the language of water, but with a little effort and practice, it isn’t hard to learn. Moving water picks stuff up and carries it. The quicker the velocity, the more stuff the river picks up and carries. Visualize two shoulder-to-shoulder boulders poking out of the water. As the river pinches between the two boulders, its velocity increases, just as water spouting from a hose increases velocity when a thumb is placed over the end. As the water speeds up when squeezing between the two rocks, its ability to carry stuff increases, and it scrubs silt, sand and gravel from the riverbed. Carrying the debris in suspension, the water happily continues downstream.

Immediately behind the boulders are voids that needs to be filled. The debris-laden water squirting out from between the rocks swirls out to both sides, reverses direction, and does its job keeping the river full behind the rocks. In the process, the water velocity slows, the water can no longer hold debris in suspension, and the silt, sand, and gravel scoured from between the rocks get deposited. If you take the time to look, you will see that there is a pillow of relatively fine sediment in the soft spot behind the rocks. The river is telling you that there was a high-velocity zone just upcurrent of the sediment.

Esoteric and no big deal, you say? You would be wrong. It’s very big deal. This is like learning your vowels in the first grade. Look at the fine sediment pile behind the rocks, then scan the river. You’ll see other similar piles, most behind rocks, but some incongruously deposited in various places. Why? Because debris-laden water was abruptly slowed for some reason.

At the edge of every single debris pile is a seam of quick water sliding past a pocket of calm water. Fish love this edge, but few anglers even know this seam exists. Sure, everyone can see seams on the surface where currents conflict and often leave a tattle-tale stream of wrinkles, bubbles, or foam. With experience, anglers have learned that this surface seam is a high-value target that should be carpet bombed with flies.

Surface seams are great, but the river is a three-dimensional world where currents at the surface are often wildly different from currents along the riverbed. If you identify the edges of dissimilar-sized substrate deposits as velocity interfaces, you have doubled, tripled, or even quadrupled the number of seams you can probe.

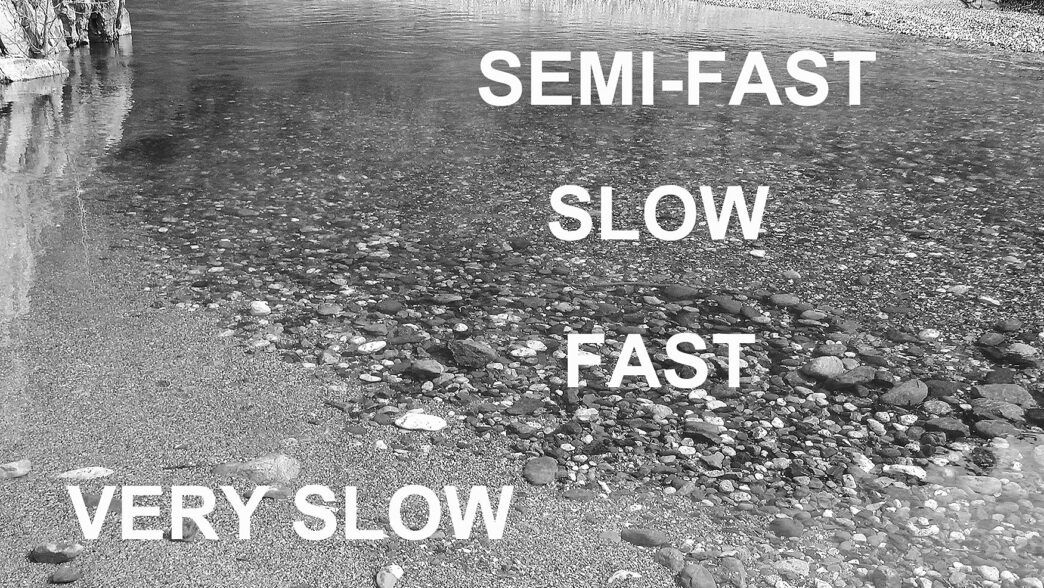

In the accompanying photo, the river is flowing from left to right. Where it collides with the wall, the river deflects left and creates an easy-to-see seam. When you’re fishing dries, this seam is probably the number-one drift in the run. Most anglers (including guides) pound this seam senseless with both dries and nymphs, then continue on to the next hole. When fishing subsurface, though, the better seam, by far, is at the interface between the fast current (identified by where it is scouring all the sand and pebbles and leaving behind large rocks) and the slow current (identified because it doesn’t have even enough velocity to carry sand). Not only do trout love edges, but (up to a point) the greater the difference in velocities along the seam, the better fish like it. As a reference: at the wall, the water is 8 to 10 feet deep, and under the word “fast,” it is about four feet deep.

At steeper drops along the river, you’ll notice that the pillows of sediment behind the boulders have gone missing. Hydrology factoid of the day: If, in a given year, a boulder is covered by water 20 percent of the time, the scouring effect of the water rushing over the boulder will negate the depositional effect of eddying water the rest of the year. Instead of berms, the downstream side of boulders will hold buckets and pockets.

Listening to the river and being aware of this subtle difference in river morphology can make the difference between a banner day and a skunking. High stick the pockets with a heavily weighted nymph or streamer and ply the surface above depositional pillows with a dry.

To make a river talk, ask questions.

We have all walked out on gravel bars or sandbars that stick into the river. How many times have you asked the river why this bar actually exists? Probably never. The “point bar” is likely being formed by debris sluiced from upstream and usually from the opposite bank. Chances are good that once you stop to look, your bar is downstream from a scour in the bank on the other shore. If you don’t see an obvious place from which the point-bar sediment was gathered, likely no one else sees it, either. Ninety-nine times out of 100, there will be an invisible undercut, usually at the outside of a bend, that is not only feeding your bar, but is also likely harboring some of the biggest fish in the river.

Undercuts are notoriously hard places to fish unless you know how. When you know how, they are ridiculously easy. There is a law in fishing that states that anything attached to your fly line will want to drift or swing into the current directly downstream of the rod tip. Here’s how to exploit that law. Loop some slack in your line hand, then hold the rod a few feet over the bank — not over the river — upstream of the undercut. Let the fly drift downstream, and when it approaches the top of the undercut, pinch the line against the cork. As the line tightens, the fly will try to swing under your rod tip, which of course is over dry land. It will swing into the undercut . . . the farther your rod tip is held over terra firma, the farther the fly will spelunk under the cut. When it has gone as deep as you dare, release the line trapped against the cork and let the current troll your fly downstream to ply the dark, sheltering overhang. It’s a pretty cool trick, actually. Keep the rod tip low. When the grab comes, instantly and aggressively pull the rod toward midriver. If you don’t immediately get the fish into open water, it will invariably burrow into the roots and become yet another big one that got away. When listening to a river, listen in stereo. We all get into ruts. When hitting a run, I invariably fish it from the same bank and in the same direction, either upstream or downstream. But it is amazing how simply crossing the river and fishing from the far bank opens up new, otherwise unconsidered possibilities. Walking downstream rather than the habitual upstream approach also creates an entirely new river.

Lies, holes, and neat spots materialize from a stretch of water I thought I knew pat.

Only after hitting the water from four angles can you be even remotely confident that it holds no surprises. I usually make the effort to do a four-way when exploring a new stream, but admittedly, I am often content to make a single run, then sit under the alders with a cold one and just listen to the river talk.