On April Fool’s Day, the joke was on me. The long-range weather forecast said it was supposed to be raining, which allowed me to procrastinate. I played all week, knowing that a rainy day was ahead. A rainy day would be perfect for sitting behind the computer, knocking out a column, and perhaps starting to think about doing taxes. Maybe even tie some flies — I’m seriously low and need to get my butt in gear.

Instead of rain, April 1 brought the most gorgeous day of the year. It was cloudless, the temperature was 75, the pond hit 60, and three turtles emerged from a long winter’s nap to bask in the sun. Insects were flying, and bluegills were swirling under mosquito minnows.

On the desk to my left was a vintage Dyna-King vise, with its supplicants of feathers and hooks loitering around the base, waiting patiently to be placed in the jaws. I was going to tie soft hackles. In a pinch, there is nothing better than these wispy, fast-food flies. I can tie one in less than two minutes (even faster, if I don’t give them two coats of head cement) and their pile grows at a satisfying rate. Soft hackles may as well be called Procrastinators, because they are invariably what get tied when I have waited until the last second to top off the box.

Soft hackles are so fast, so simple, and so painless to tie that it is in my personali-ty to judge them as nearly worthless. As they say, no pain, no gain. A fly that takes 20 minutes to tie must be better than a two-minute fly. It is the same reasoning used when going into a fly shop and breezing past the bargain bin to buy a five-dollar fly featured at the counter. This year’s “hot new fly” encourages sales over common sense, and I’m no less guilty than the next guy.

In the real world, though, boring old patterns that have withstood the test of time and reappear in bins decades on end are the hot fly. They must work pretty darn well to compete with the flashy newer models. There is nothing flashy or new about soft hackles. In 1496, in an essay called “A Treatyse of fysshynge wyth an angle,” printed in the second edition of The Boke of St. Albans, Dame Juliana Berners describes the “donne” fly, which is known today as the Partridge and Orange Soft Hackle. Over five hundred years later, this humble fly still holds its own against bins crowded with the likes of Articulated Butt Monkeys, Zoo Cougars, and Grumpy Frumpies. Open any fly-fishing catalog, and you’ll go numb after thumbing through page after page of flies. Chances are good that most of these patterns weren’t in existence five years ago, and chances are just as good that most will be faded memories five years hence. What is it that keeps a five-hundred-year-old pattern competitive and profitable? It works.

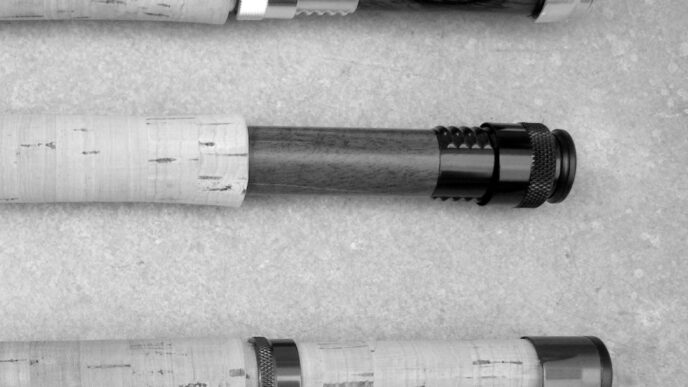

The original Partridge and Orange was simply some orange thread (perhaps silk or floss) wrapped around the hook shank from above the barb up to near the eye. The stem of a small, soft feather from a grouse or partridge was tied to the hook, seized by its tip and turned once or twice around the shank, then tied off with the same orange thread. A neat bump of a head was built with a few more wraps of thread, and the fly was done. A thread, a feather, and a hook. Deadly.

Sometime in the 1600s, an innovative tyer created a “new and improved” version of the Partridge and Orange by dubbing a small mound of fur immediately behind the feather. The bump kept the barbules flared and when viewed as a silhouette against the sky gave the fly a little more meat. Kind of like the body of some bug.

I tie both the traditional, slim version of the Partridge and Orange and the four-hundred-year-old “new and improved” version with the dubbing bump, or even dub the entire shank and rib it, if I get supremely creative. The bump does create a nice, scraggly silhouette, but without the bump, the feathers have twice the room to undulate and breathe. Which one is best? I suggest fishing both styles at the same time as a point and dropper and let the trout be your judge.

Fishing a soft hackle is as easy as tying one. There is no possible way to do it wrong. Arguably the dumbest way to fish is to stand in the middle of a stream and just let the fly hang in the current.

When using soft hackles, sometimes dumb isn’t so stupid.

With a 9-foot rod and a 6-foot wingspan (your outstretched arms reach as long as you are tall), a 6-foot person can effectively cover 24 feet of water and always have the fly directly downstream of the rod tip. Get in the middle of the river (about 20 feet upstream of a riffle or tailout is perfect) and hold the rod pointing toward one bank. Let the soft hackle hang in the current about three rod lengths downstream, then smoothly swing the rod tip upstream. After pulling the fly about 10 feet upcurrent, drop the rod tip back to the starting position. This introduces slack and allows the soft hackle to drift downstream with barbules outspread like an octopus as it sinks toward the streambed. After a 10-foot drift, the line tightens, the hackles pulse closed, and the fly swims toward the surface on a taut line. The grab invariably comes as the fly is ascending, and the fish sets its own hook.

Next drift, bring the rod tip about 18 inches toward the center of the river, away from the bank, and repeat the drag, drift, and ascend drill. Repeat again and again, until you finish with a drift that starts with the rod tip facing the opposite shore. You’ll have covered 24 feet of river. Take a few steps downstream and start again. With a soft hackle or two, this is a sure-fire way to hose a run.

Most anglers cast down and across, then let the soft hackle swing on a tight line back to directly downcurrent of them. This is fine, but so boring that you might want to mix it up a bit. You can slow the swing by mending out into the current or speed it up by mending toward the shore. Better yet, have the bug swim erratically by making short, quick mends into the current, then back toward shore again. At the end of the swing, be patient and allow the fly to flutter in the current for a moment before making the next cast.

During a hatch or spinner fall, rub fly floatant on the leader and tippet, but not the fly. Cast your line quartering upstream, then flake soft mends behind the fly as it wafts by for a long, drag-free drift. The soft hackle will hang just under the surface. Whether fish think it is a drowned spinner or an emerger stuck under the film is irrelevant as long as they eat it, and they usually do. After five hundred years, you’d think they would learn.