At the moment the first bird graced the skies and as soon as mammals evolved on the ground, fly-tying materials were born. Despite all of the advances in materials technology since, few items in the human-devised arsenal can beat the natural qualities of fur, feathers, and hair for creating flies that look and behave like real bugs.

There’s a reason for that. Fly fishing is a sport of tapers. For example, our basic tool, the fly rod, is simply a long, tapered tube designed to amplify the energy of your hand. The hand doesn’t move very far or fast, but when it stops moving, the energy from the hand is transferred to the thick end of the tube. As this energy travels toward the skinny end, it faces decreasing resistance that, by the nature of physics, requires its velocity to increase.

At the skinny end of the tube, the energy leaps into the thick end of the fly line and shoots outward, again facing less and less resistance, and it moves faster and faster as it travels with the taper. At the tip of the fly line, the energy connects with the thick end of the leader and flashes out to the skinniest tip of the tippet. By the time the energy reaches the end of the tippet, what was once a relatively slow swishing of your arm has created mass in motion approaching the speed of sound. What happens now all depends upon whether you used natural or synthetic materials in your fly.

Like fly rods, lines, and leaders, most natural fibers are tapered. The slightest motion of the fly or waft of current will cause these fibers to tremble and shake as the energy of the movement is transmitted down the taper.

Synthetic fibers aren’t tapered. Virtually all of our synthetic fly-tying fibers are plastic. The chemistries of the various plastics differ greatly, but the end product is almost always pulled or extruded through some sort of die, then chopped into convenient lengths. As a result, the fiber has a constant diameter. Whether we are tying size 22 midges with SuperFine microfiber dubbing or constructing 12-inch saltwater patterns with shanks of Slinky Fibre, the result is a fly that looks nice, but lacks the “life” of the same fly tied with natural, tapered materials.

There have been valiant attempts to create tapered plastic fly-tying fibers, but for one reason or another, they have never really worked. The butt was too stiff relative to the tip, the fabric was too coarse, or the material matted into a big wad of cat scat. Perhaps someday someone will invent the right stuff, but it certainly hasn’t happened yet.

Synthetics have their place. It is really hard to find 12-inch bucktail, some plastics have a transparency and flash factor difficult to find in nature, and plastics certainly stand up well against toothy critters, but please don’t fall into the trap of using synthetics by default.

Natural materials can be matched to a fish’s prey by the way the prey behaves in water. When imitating stillborn or drowned insects, soft, fluffy marabou or mallard flank will waft in the current like living smoke. These materials perfectly replicate the slipping shuck of a bug crippled during emergence. The exact same pattern tied with stiff wood duck or merganser flank will vibrate like the breathing gills and twitchy legs of a living nymph or scud. Sometimes it isn’t the fly that isn’t catching fish, it is the materials the fly is tied with that aren’t matching the hatch.

Many furs, such as beaver and otter, have scales. Under magnification, the hairs look like shoots of bamboo, one segment jutting out from a slighter larger segment that is jutting from another and another. It is the scales at the juncture of these segments that grab adjoining hairs to create felt or dubbing, and the same segments grab the tying thread. Other furs are soft and crinkly and they naturally nest together. It is these frizzes and scales that make dubbing with rabbit or beaver so effortless and dubbing with Antron such a pain.

Fur is absorbent, which can be a plus or a minus, depending on conditions. Many furs turn dark or change color when they absorb water. Chew on your bug until it gets soggy, then hold it up against the light. It may be several shades removed from what you imagined. It might not have changed all, but until you apply the chew test, you’ll forever be fishing blind.

For an even more realistic view from a trout’s perspective, drop your natural-fur fly into a glass of water and hold it up to the light. Not only might the fly be a different hue than when it was dry, it will also look charged with life. Unlike any synthetic I know of, most fur becomes translucent along the cuticle when it is immersed in water, and each wafting fiber glows as with an inner light. It demands attention.

Natural fibers absorb water, which is perfect for a nymph, but isn’t a bonus if you want your fly to float. Fortunately, natural fibers also absorb liquid floatants, and their rough surface holds desiccant powders much better than slippery plastics. If you want a nymph coated with a shimmering blanket of bubbles, use a natural fiber, rather than Antron or Z-lon, dunked in desiccant.

If you want a material that keeps the fly afloat, it would be hard to imagine anything better than deer, caribou, or antelope hair. These hairs are nothing but tubes packed with air-filled cells resembling microballoons. Some of my favorite flies, such as the Perfect Little Yellow Stonefly, have a body of spun deer hair and a deer hair wing. With a few false casts, they float untreated, even after being chewed by trout and covered with slime. A few shakes of desiccant, and they literally skate.

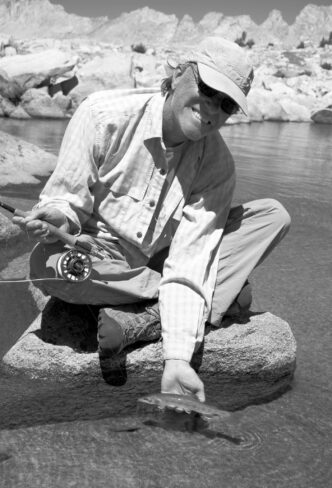

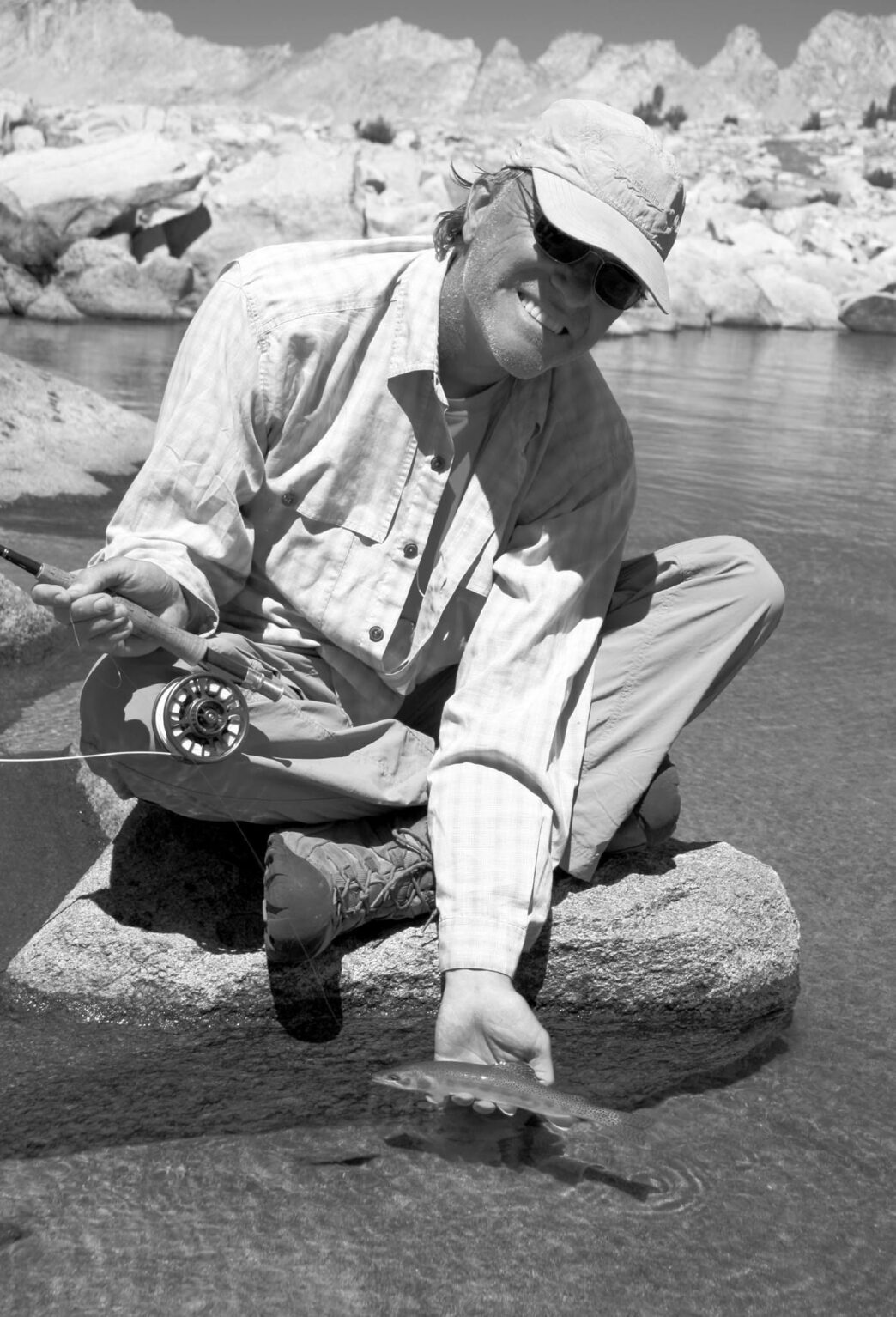

I have many uses for bucktail, but little use for elk or moose. Bucktail is magic. It is stiff and easy to work with at the vise, but instantly absorbs water and becomes marabou-soft in water. It has the kind of taper a master rod maker can only dream of replicating. It dances in calm water and rips with the strip. Picture a squid pulsing through shafts of sunlit waters, and you’ve imagined a bucktail streamer swimming past any game fish of your choice. For good reason, the bucktail jig has likely felled more fish than any other fly, popper, or lure in history. A bucktail Clouser is worth a dozen of the same pattern tied with plastic.

Unlike bucktail, elk doesn’t flow through the water like liquid smoke, nor does it float like deer. Many tyers, especially production tyers, use elk because it doesn’t flare, stacks easily, and resists getting cut by thread. That’s nice for the vise or shadow box, but on the water, elk plays second fiddle to most other materials. Whenever you see elk in a fly recipe, reflect on its purpose and consider replacing it with deer or bucktail. You might be pleasantly surprised.

Winging material is highly overrated. Seen from under the water, the wing of a fly is nothing but a shadow over the body. It’s hard to beat a frizzy tuft of calf tail or snowshoe hare. A small waft of this stuff is enough to simulate a wing without sinking the body under its weight. I like stacking a chunk of white calf-body hair against black calf. The silhouette is fine, and the contrasting dark and light colors help me see the fly as it floats through areas of shade and glare.

Many tyers put great importance on the floatability — the specific gravity —of winging material. Imagine strapping a life jacket on the top of your head. It probably won’t keep you from drowning. A heavy polypropylene wing may float, but its weight, especially when combined with water sucked up between the fine fibers, tends to push the body of the bug underwater.

Revisit the properties of native materials. Man-made petroleum fabrics may match every conceivable color of the spectrum, but these synthetics are just one more step removed from the reason why fly fishing is fly fishing.