At some point in your fly-fishing career, it’s going to dawn on you that despite any technical proficiency on your part, some days spent “afishin’ ” are better than others. If you are one of those fastidious fly anglers who keeps a stream or lake journal, you’ll probably get that idea sooner, rather than later, but it occurs to almost everybody who ever wet a line.

You could, I suppose, keep enough detailed information in your log to develop a comprehensive understanding of when the fishing is good and when it isn’t. If you collected a range of data and looked for correlations with “outside” influences on the fish, you very well might come up with something that resembles the solunar tables created by angler/author John Alden Knight way back in 1926. An inventive fellow, Knight figured that the phase of the moon must influence the way fish do or don’t feed. He also extrapolated this idea to cover the best times to go into the field for deer and other game.

This may sound like a lot of mystical mumbo jumbo or something akin to getting your fortune told or your horoscope read, but it isn’t. Actually, it’s a fairly accurate system that a lot of fishing professionals swear by. I know some fishing guides and tournament anglers who use the tables to help them make their income. You can’t get much more serious than that. It’s not as odd an idea as it first appears. We know that a number of creatures, from corals to grunion, spawn in strict accordance with the moon phase. We also know that many coastal species of saltwater fish time their feeding to the tides — another effect generated by the moon and sun. If these aquatic creatures are influenced by the changing relative positions of these celestial bodies, chances are that it works for almost all creatures. A simple search on the Internet for “Solunar Tables” will direct you to a number of sites that offer predictions for the best times to go fishing or hunting.

Actually figuring out what is happening on the fishing front can bring a lot more than just the solunar tables to the, well, table. There’s a lot to be said for paying attention to the variables that might figure into the behavior of your favorite game fish. Most are subtle, but if you watch the world around you with a keen eye for small details, you’ll be surprised at how much you might be able to discern about the behavior of fish and game.

The change in the amount of daylight versus darkness throughout the year is one such factor. Biologists refer to the relation between daylight and darkness as the “photoperiod.” There’s plenty of evidence that in bass, the lengthening photoperiod in the spring triggers the hormonal response to begin producing eggs and getting ready to spawn.

Of course, water temperature also influences spawning behavior, although over the years I’ve come to think that the more daylight you get, the more the bass want to move into the shallows from their winter deep-water locations — and the more they feed in preparation for the mating and spawning rituals that will follow. While I don’t disregard the influence of water temperature, I’ve seen plenty of evidence that bass, among other species, will begin to move into the shallows when the length of the day says it is time to do so, even when temperatures are much cooler than considered “normal” for that behavior.

I used to subscribe to the idea that the onset of spawning activity requires water temperatures of around 60 degrees. In more recent times, however, I’ve come to realize that bass become active at far lower temperatures and that prespawn feeding sprees can start with water temperatures in the low to mid 50s.

What this means is that even in the middle of winter, once the photoperiod begins to lengthen, a week of warm, springlike weather (not uncommon in California) in the midst of an otherwise unremarkable cold season can trigger early action. Even an up-tick in water temperature of two or three degrees can put bass in a feeding mood. I once fished a nearby lake in February with a local bass pro. We found that anywhere we could locate areas where the water temperature was just two degrees above the surrounding lake, we would find bass feeding aggressively. Most fly-fisher folk think of April and the traditional opening of the trout season in the eastern Sierra as “spring,” but spring for the warmwater fly angler can start as early as mid-February.

The time of day matters, too. We know that bass, like most wild creatures, are fine-tuned to hunt during the low light levels of dawn and dusk. At least, that’s the idea. What may be closer to the truth is that humans, being creatures more inclined to hunt in daylight, find the fishing is better (that is, easier) when early morning or late evening light is just enough for us to see adequately. Bass, like so many other critters, actually feed all night long, using the cover of dark to camouflage their activities. This is, of course, tempered by the two factors already mentioned, photoperiod and temperature.

We all know a few fishers who are at the top of their game. These men and women just seem to know when the best fishing is about to take place. They may be analytical and use all sorts of theories and formulas to guide them in their sport, or they may just have a “feel” for nature’s operating machinery. They use their eyes, ears, and life experiences to develop a better understanding of what is happening around them

This understanding actually boils down to a fairly simple set of rules. First, it helps to be observant and to trust your instincts. I once was told by an outstanding angler that his fishing seemed to improve if he could see small critters playing and feeding along the shore. He figured that if the dry-land wildlife was engaged in hunting around for food or chasing the other sex through the trees, the chances were good the same thing was happening below the surface, as well. Although this might seem like a loosey-goosey approach to angling, correlating two phenomena, such as activity on land vis-à-vis that in the water, is the first step in the scientific process.

Second, watch the other predators. (And yes, Virginia, you are one. Even if you practice all-out catch and release, you are following ancient rules of predator behavior, or should be.) For example, if I see hunting birds such as herons or egrets stalking the shore and spearing the occasional small baitfish, I can figure that the prey fish are in the shallows, and by extension so will be the larger predatory fish I hope to catch.

Sometimes it’s even more obvious. A screeching, squawking horde of gulls or grebes diving and coming up with threadfin shad in their beaks is a signal to rush over and cast a streamer into the melee.

Another, sometimes less obvious bit of behavior is the increased action you get during periods of overall low light levels. Not only are dawn and dusk obvious times to fish (all other things, moon phase, temperature, and so on, being considered), but an overcast day is often better than one of blue skies and bright sun. All predatory fish like the cover supplied by low light, and a foggy or even rainy morning or a cloudy, slightly warmer spring afternoon can bring out the best in big fish that use the lower light levels to come into the shallows to hunt.

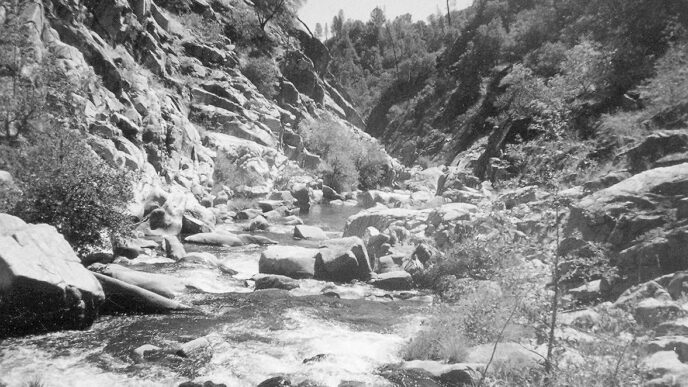

I recently saw a good example of this while photographing a fly-rod tournament on the Kern River. The fishing during the morning session was fair at best under bright skies and in warm temperatures, but during the afternoon, the sky clouded over and rain began to fall. The action picked up, and the fish caught were larger under cloudy skies. It was a modest improvement, but a significant one.

Air movement is another factor. A breeze, even on a bluebird day, can riffle the water’s surface, making it difficult to see below the surface. This is a form of cover for fish, and it can stimulate a feeding spree. This past autumn, I fished a little, pretty pond in a local trailer park. It holds panfish and enough bass to provide a fun outing, and it isn’t on anybody’s list of angling hot spots. I was mostly fooling around, trying to hook a bluegill or two while the wind was absent.

Like clockwork, the afternoon wind from the southwest picked up at about five P.M., about the same time that shadows began to lengthen across the water. Soon, the breeze-wrinkled surface of the pond began to be punctuated by tiny blips that signaled small baitfish dimpling the surface, taking gnats and midges. It wasn’t long before I noticed a larger swirl. I dropped a small cork popper near the dying ripples created by the larger fish and was rewarded with a strike from a decent bass that had slipped into the shallows only a foot or two from the grassy bank in search of smaller critters to swallow.

As long as the fitful breeze fluttered over the surface, I caught bass within a couple of feet of the bank. The action did not end until it was almost dark, when the breeze died and the surface of the little pond became like a mirror again.

Along with all these variables — solunar period, length of daylight, temperature, time of day, cloud cover, wind, and other possible intangibles — many warmwater fly anglers fail to take into account water flow. Wind can create water movement. The windy side of a lake may not be the easiest thing to fish, but a wind that piles up foam and flotsam along the shore can also drive schools of baitfish or hordes of insects to that location, triggering a feeding spree. A wind-created current can be a blessing.

So can artificial currents started and stopped by the electronic whim of the computer system that controls water flow in and out of water storage reservoirs. I’ve written in the past about treating many of our larger reservoirs more like big, sluggish rivers than like lakes. This is most true of those that are part of the California Aqueduct system. Impoundments such as Pyramid (the one in California, not the big Nevada reservoir), Castaic, Silverwood, Perris, and others have a lot of water transported through them. Often there is manmade current at regular intervals. When this is happening, the fish in the lake react to the current flow, even though it may be almost undetectable by us, and feed in patterns you can exploit. All of the things I’ve mentioned in this column contribute to the way fish of all sorts behave. What it boils down to is this: Paying attention to the world around you makes your fishing better.