Spring is a time when bass fishing becomes an “in your face” form of the sport — when you probably can draw a strike by getting your fly right in a bass’s own personal space. The urge to spawn brings bass into the shallows, and bass defending their spawning beds there will attack pretty much anything that enters them. That makes these fish a target for flies and presentations that you might not use the rest of the year.

Lengthening days and the warmer water temperatures that result from more sunshine trigger the spawn. This concentrates bass close to the shore — or at least in the shallows. Some years ago, I lucked on to bass spawning out in the middle of a lake on a not quite revealed island. This hump of submerged earth was about an acre across and rose up to form a perfect spawning flat, well isolated from any shoreline. The water on top of it was about four feet deep, and the only thing that gave it away was a safety buoy placed there by the lake patrol. The place was loaded with bass and their spawning beds.

For bass, it has long been taken as fact that the spawn begins when the water temperature is around 60-plus degrees. That, of course, depends on a lot of factors. Northern-strain largemouths spawn in slightly colder water, and smallmouths don’t follow the 60-degree “rule,” either. Florida-strain largemouths, which are common in many of our California impoundments, may spawn in warmer temperatures. There are even individual likes and dislikes among fish of the same species. As a result, spawning activity may occur in the same lake at varying temperatures and times for several weeks each spring.

Since different lakes reach spawning temperatures at different times of the spring, you actually have quite a number of weeks for fishing the spawn. The lowest elevation lakes will reach spawning temperatures first. By initially fishing the valley lakes, followed by those in the foothills and the higher mountain lakes that have bass populations, you will lengthen the time available for spring fishing.

Down here in Southern California, where I do most of my spring bass fishing, you might find bass beginning to bed as early as February on some of the lower-elevation lakes such as Otay or Castaic and as much as six weeks later on Silverwood, Pyramid, and Morena. Later in the spring, you can locate spawning bass at Big Bear or Cuyamaca. This works everywhere else in the state, too, so pick your own list of lakes this spring and follow the spawn from low altitude to high.

I don’t know how completely my experience matches the real world, but I get the sense that our bass begin to stage to spawn earlier than we originally thought. Once the water temperatures in your local reservoir or pond reach the mid-50s, you should start looking for bass to be in the shallows at least part of the day and should keep a sharp eye out for evidence of the males creating their spawning beds.

One of the things I like most about close-to-shore spring spawn angling is that it frees you from float tubes, boats, even waders. You can wander the bank of your favorite bass water with your feet dry and warm and still be within easy casting distance of the bass and their beds. About the only thing you have to contend with are the fitful spring winds that ruffle the water.

Depending on the type of lake you are fishing, spawning beds may range from very easy to very hard to detect. In lakes with substantial tule or bulrush growth around the edges, many spawning beds may be tucked back into the weeds and very difficult to see. In lakes without so much natural cover, the beds may be more visible, but placed deeper, especially if the lake is subject to constant changes in elevation as water is pumped in and out, or if it has a high level of boat and personal watercraft activity

I’ve seen bass bedding in water less then three feet deep in relatively undisturbed shallow coves that for one reason or another are difficult to get a boat into or are just overlooked by anglers. Big Bear Lake in Southern California has a couple of spots like this, and the rocky shore of Lake Hemet, high up on Mount San Jacinto, is another. You can walk the bank as the water temperatures come up and spot the slightly lighter beds, swept clean of leaves and other bottom trash by male bass. Bluegills make similar beds, as do most of the panfishes. If you spend some time just watching with a good pair of polarized sunglasses to cut surface glare, you may be able to see fish actually spawn and, later, raise their young of the year. It’s a great way to learn fish behavior.

The spawning beds are most often nearly circular, with a diameter of a foot or so. The males create these beds much the same way that a trout creates a spawning area in stream gravel. They use their tails to sweep aside anything they don’t want there, and once the spawning bed seems adequate, they hang around, trying to look virile and important — like teenage boys at the mall on Saturday — so as to attract a female to deposit her eggs in the bed.

Don’t expect a spawning bed, even a fresh one, to stand out like a sore thumb. I’ve seen some on white sand bottoms that were fairly obvious, but most often they will be difficult to detect, especially those in water deeper than 3 or 4 feet. You will find them as deep as 10 to 12 feet at times. And as I noted, on lakes that have a lot of boat and personal-watercraft traffic or water-level fluctuations, bass often bed much deeper than they otherwise might.

During spawning, the males are highly pugnacious and will attack anything they see as a threat to the bed or the eggs. This means you can stroll the bank with nothing more exciting than a Woolly Bugger and catch these males. Sometimes you can hook the same male two or even three times in a single day. I don’t recommend this, because that much handling is hard on the fish. I keep moving so as not to concentrate my fishing in one particular spot. (By the way, if an angler practices catch and release, then I don’t believe fishing during the spawning period affects the health of a bass fishery. That said, holding your catch in a livewell and then releasing these fish far from their spawning beds is probably not a wise idea.) The males are always smaller than the females. If you are after a really big bass, targeting the females is the way to go. That pound-and-a-half bass you catch off a bed will almost certainly be a male. Anything much over five pounds is usually a female, and all the really giant bass will be females.

Catching the larger females off the bed is a much more chancy proposition. They don’t spend a lot of time on any one bed. A big female may lay eggs in more than one bed and doesn’t generally hang around to parent the eggs and young bass, the way the male does. This means that the angler who fishes a chosen water as of-ten as he or she can is likely to be the one who catches the best fish. Being there simply counts as much as or more than the fly you use or the presentation you make.

The trick to spring fishing for bass on the spawning beds, if there is one, to be able to spot the beds first and the fish itself second, because not being able to see the bass is not a serious handicap. It takes only a bit of spring bass fishing for you to realize that a bass’s color and pattern are an almost perfect form of natural camouflage.

As I noted, the males hang around the beds defending them from predators that might eat the eggs or attempt to eat the young-of-the-year bass after they hatch. If you get your fly to drift across the bed, you’ll likely get a pickup from the male, and if you are very lucky, you might hook a female.

When sight fishing for bass in this way, remember that if you can see the bed, the bass that made it can probably see you. Calm days with little or no wind to ruffle the water are great, but in the spring, breezes are more the norm. This is sneak fishing at its best. You have to detect the bed, then back off a ways and try to find that happy medium where you can just barely make out the bed and the bass doesn’t know you are there.

A fairly long leader is an advantage here. The main reason you need a long leader is that to get a response from the fish, you have to cast beyond the bed and then retrieve the fly to and through it. When fishing for bass during other times of the year, I don’t much care about having a long leader, but during the spawning period, I think it helps if you are not dragging a thick fly line through the area. I therefore use tapered leaders between 9 and 12 feet in length. This is one time when I recommend a quality tapered leader. When bass bug fishing, I often just use level leaders, but a leader that tapers is better for this application because it helps turn over the fly and parts of it are less visible than a heavy level leader.

You can successfully fish bedded bass on quiet waters with a floating line. With the long leader and just a bit of weight in the fly, you can get down four or five feet. If the bass beds are deeper than that, you may want to consider a sinking line.

I tried using a sink-tip line on and off for several years, but finally gave it up for full sinking lines. The late Dennis Ditmars, a great bass fly angler from the San Diego area who caught some huge bass on the fly, taught me that a full-sinking line is easier to cast and just works better. These days, the reason why I often fish a fast-sinking line is because it keeps me from fidgeting around while waiting for the darn thing to depth I want. If you are one who prefers fishing a floating line, just stick a couple of short lengths (18 to 36 inches) of lead-core line with loops on both ends into your vest and add one of these between the line and leader to help sink the fly deeper than four or five feet. It isn’t a perfect solution, but it does work well enough to catch fish.

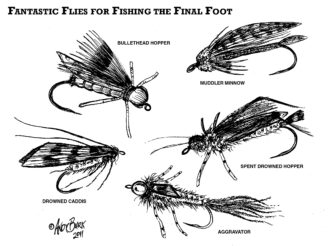

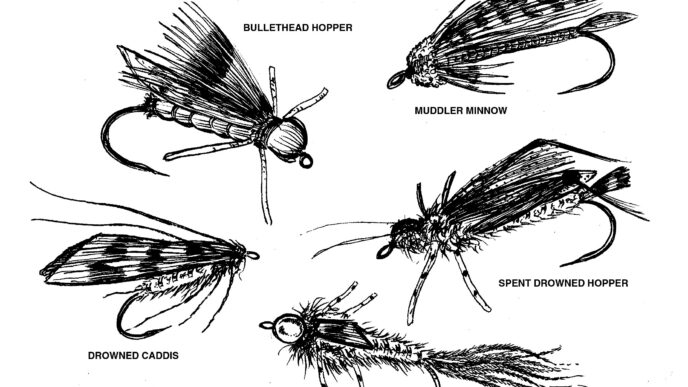

Fly selection is pretty simple. While bass hate anything that intrudes on their spawning space, some body shapes probably work better than others. A little streamer fly that looks like a bluegill just drives bass on the beds nuts. Bluegills are predators of bass eggs, and any bluegill that gets too close will be attacked at once. Curiously, the bass may not eat the bluegill. I’ve seen males snap up a threatening bluegill, swim a short distance away from the nest, and spit the dazed ’gill out. It’s not a feeding thing, just a reaction to the threat. The bluegill goes staggering off, trailing scales and looking a bit worse for wear, while the bass returns to guard duty. Something like Dave Whitlock’s Sheep Shad tied in bluegill colors is a great fly for prospecting bass beds. I’ve resorted to fishing a large (size 2 to 4) Hornberg on bedded bass with some success. Another productive fly pattern is a Marabou Muddler in white or yellow.

Bass don’t care for salamanders, either. They quickly snap these up. A Spuddler works pretty well as a salamander (waterdog) imitation, as does the old Whitlock Hare Water Pup. Again, a soggy Marabou Muddler will suffice, if you have nothing else.

Any or all of the various imitations of the plastic worm will produce strikes. I won’t bother to list them, because almost every bass fly angler (including me) has created his or her own worm substitute. Mine are mostly made of rabbit fur, and any long, slinky fly with a sinuous action will catch at least some bass.

For bass bedded in deeper water, the trick — which I’ve written about before, but it bears repeating — is to use an imitation of the bass angler’s lead-head jig. The original jig fly, and still one of the best, is an awful looking thing created by the late Tom Nixon, whose book, Fly Tying and Fly Fishing for Bass and Panfish (A. S. Barnes, 1968), got a lot of anglers into that aspect of the sport.

Tom’s original creation, which he quite accurately described as a fly angler’s version of the modern bass pro’s rubberskirted jig, is called the Calcasieu Pig Boat, named for a Louisiana river that Tom fished a lot. It is sometimes tied on a 45-degree or 90-degree-bend jig hook and uses a lot of strands of rubber-leg material to create the flowing collar. Some fly fishers tie it with trailing feathers or rubber leg that mimic the claws of a crayfish. Tied in almost any color, though, it catches bass.

I used to tie Pig Boats in pure white for Dennis Ditmars. He had learned and developed a great angling technique, created originally, I think, by master bass angler Mike Long. Mike recognized that bass in many of the lakes he fished bedded much deeper than you might expect, as much as 8 or 10 feet down in some heavily pressured waters.

Not being able to see the fish and barely able to detect the beds at those depths, Mike got the idea of fishing an all-white jig. This is a different kind of sight fishing. Instead of looking for fish you can’t see anyway, you simply cast over the bed and slowly creep the jig (or in our case, the jig fly) across the spot. If the barely visible white jig suddenly blinks out, you set the hook, knowing that something unseen — and maybe very large — has swallowed the fly.

If you want step-by-step tying instructions for the Calcasieu Pig Boat, visit http://warmwaterflytyer.com/corner.asp for a fully illustrated tying sequence.

This spring, taking the time to stalk bedding bass near shore is a great way to spend a day of fishing. You don’t have to travel to distant mountains to find great fly-fishing sport. It’s as close as your nearest bass pond.