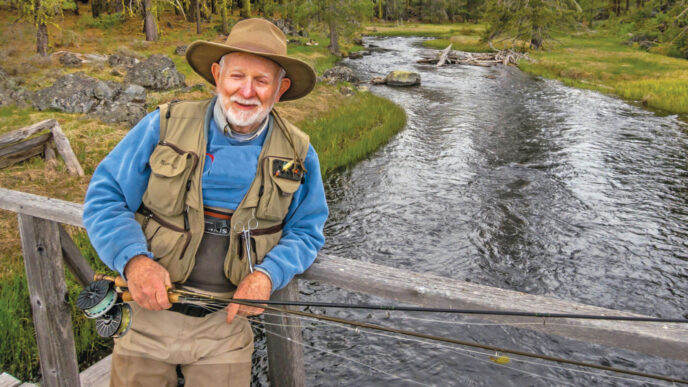

Editor’s note: Rick Bean, the writer of our warmwater column, is currently taking time off, so we’ve asked Trent Pridemore, a lake angler par excellence, to contribute and broaden the focus to stillwater angling. We think you’ll find his observations useful and thought-provoking.

Sight fishing on still waters, where one casts to fish that can be seen or to signs that reveal or suggest the presence of fish, is one of the most rewarding forms of fly fishing. It may be the most technically demanding form of our sport, because it requires excellent eyesight, fast reactions, keen powers of observation, and casting skills that include distance and accuracy. Then throw in the need for an understanding of fish behavior and a solid knowledge of aquatic biology. The skills developed when sight fishing in fresh water will make you a better saltwater angler, whether you are targeting fish such as snook, redfish, bonefish, permit, or tarpon. Likewise, those same skills, when developed in a saltwater environment, are very applicable to freshwater venues for trout, bass, carp, and panfish.

My first experience with sight fishing for trout came in 1972 at Lake Davis. I was on an exploratory trip to Eagle Lake. A stop in Portola for provisions took me to a small hardware store where a woman, Evelyn Gamble, was tying flies. She asked me, “Why are you headed to Eagle? Davis is fishing red hot.” I stayed at Davis four days, calling home and the office from a pay phone to say that I would be a day late, something that I did very rarely. Evelyn tied me some flies, gave me a map to Cow Creek, and passed on some pointers. She directed me to wade from shore and to look for V wakes, slicks in wave tops, or the backs of fish in a chop. She also suggested that when the wind died in the evening, I should look over my shoulder and I would be able to spot noisy fish that had moved behind me, into skinny water, looking for food they knew would be there.

That August trip was a fly-fishing epiphany for me. The angling action occurred from 7:00 P.M. until dark and beyond. During the day, I drove to Portola and bought small glass vials from the local pharmacy that would hold stomach samples, and I crudely tried to imitate the aquatic bugs that I found. I would learn later that they were cased caddisflies, and that was why Evelyn’s version of the brown and grizzly Buzz Hackle was a simple, but very good imitation. It was the first time, other than on a stream, that I was casting to trout that I could see or to the subtle signs that they can make.

Sight Fishing for Stillwater Trout

Even at a fertile lake with a rich fish biomass and abundant insect populations, blind casting catches few trout. To locate cruising trout, I start with a search for shoals and structure. I look for breaks in the contour of the bottom, points, old channels, bays that have tributary streams, inlets, outlets, and weed beds. The edges of weed beds and underwater gardens are always good places to look, as are springs and shoreline seeps.

Water depth is one of the most important things to consider. Search the inshore waters and move out into deeper water in increments. Where the trout are feeding can vary from one end of a lake to the other and from windward to lee side as well.

You can sight fish to trout that you can’t actually see, because in a float tube or boat, a portable Bottom Line Side Finder or other mounted sonar device can find fish. These devices aren’t always perfect and miss some trout on the bottom or in weeds, but will tell you whether there are fish in your area and what the surface water temperature is. Study your electronic wonder, learn the cone angles of both the vertical and horizontal scans, and trust them. Cast to blips on the horizontal scan, just as if you have seen the fish.

Stealth — or the lack of it — can determine whether an angler casts to sighted fish or the fish flee from a sighted angler. Keep a low profile. And be a quiet as possible. If you are wading, a soft entry and slow movement makes sense, particularly early in the morning, when the surface is dead calm. If you’re afloat, things such as banging the bottom of a boat or a noisy anchor release will send fish scurrying. Carpeting helps. Often I will try to drift into a productive area or row in, rather than use a gas engine or electric trolling motor. In wind, I throw out a drogue to slow down my drift and cast to the sides rather than to water that has been crossed. Float tubes are probably the least disturbing floating devices, but if you are into fish, minimize your activity. Again, cast to your left and right, rather than drag your fly through water through which you’ve kicked.

When to fish can be as important as where. The windows of opportunity to sight fish often arrive between long periods of inactivity. At Lake Davis and other places over the years, I learned to identify and concentrate on prime times so that I would be there when it counted. Seasonal prime time centers on major events such as Blood Midge hatches, Callibaetis emergences, Hexagenia hatches, damselfly migrations, baitfish concentrations, and the presence of snails and will vary from year to year and lake to lake. In extremely cold weather with cold water temperatures, it might be a waste of time to fish until water temperatures rise a degree or two. During the summer doldrums, you want to be on the water early and late, seeking water temperatures that fish tolerate. I rarely fish through an entire day. I might try to be in position to catch a mid to late morning Callibaetis emergence, take a break around one or two P.M. when it is over, and return for late afternoon fishing. I want to be as mentally and physically sharp as possible during the period of maximum fish activity. Most of your fish for a day could come in a one-hour window. You have to be opportunistic and jump when the time is right. It’s hard to generalize about just when those daily prime times occur, though. They vary with the season and the hatch. Damselflies migrate to shore in mid to late morning, and their migration can be mixed with a Callibaetis hatch. Most large Blood Midge hatches that I have seen have come during calm late afternoons.

When you’ve found fish, the next problem to solve is identifying and imitating the food that they’re eating. I always try to observe and record things. A well-kept log will dial you in a year later when you’ve forgotten a lot. At Lake Davis, in the early years after the dam on Grizzly Creek was built in 1967, there was an explosion of aquatic insects. Some were indigenous to the local streams, and others migrated or were blown in from regional bodies of water. New lakes, and particularly new lakes in fertile alkaline drainages, tend to experience rapid increases in fish and aquatic insect populations.

In fertile lakes such as Davis, an abundance of aquatic insects draws fish to the upper water column, and sight fishing opportunities can occur more frequently than in lakes in which the fish, of necessity, have to look for food throughout the water column. Stomach samples often show an abundance of one food type, but it is rare to find only one menu choice. You might find several small dark beetles and a brown leech amid hundreds of small olive midge larvae or light-charcoal-tinted damselfly nymphs. That’s one of the reasons that I like to use two-fly rigs. I generally start by looking for major aquatic insects such as Callibaetis mayflies, caddisflies, midge larvae, pupae, and adults, and damselflies and dragonflies. Ants, termites, water boatmen, leeches of all colors, and aquatic beetles appear at times through the year, and you could be out on the lake when yellow jackets or aquatic moths are falling, too. (Developing a stillwater fly box that contains effective imitations that cover most situations can take years.)

We all hope to cast to rising fish, and rise forms tell the sight-fishing stillwater angler a lot about what bugs fish are taking and at what stage in the insects’ life cycle. They can vary from classic head-and-tail rises, where trout are taking nymphs millimeters below the surface, to swirls when they are eating emerging midge pupae, to gulping rises for adult mayflies in the surface film. The rise forms might be dramatic and obvious, as with the blowups on Hexagenia adults, or subtle sips of nearly invisible down-wing mayfly spinners or miniscule midge adults.

But cruising fish often are feeding below the surface, and sight fishing can also involve targeting subsurface flashes, in which the turning body of a feeding fish catches the rays of the sun, or V wakes on the surface or slicks in wave tops signal a moving fish underneath. Sometimes casting to a hunch pays off.

Either way, read and try to anticipate the movement patterns of your quarry. Trout tend to cruise in an arc, but cruising fish can be unpredictable. Sometimes they will take food in a regular pattern every 5, 10, or more feet over a considerable distance. At other times, they will move in one direction for a while, then reverse and reverse again. Trying to get a fly in front of a cruising trout can drive you crazy.

Trout also have an uncanny tendency to cruise just out of casting range. Then, just as you are straining to make a 60-foot cast to a rising fish, one will jump 10 feet from your float tube. That’s why casting skills are so important in stillwater angling. You need to make long, accurate casts with only one or two back casts. False casts can line your fish, and you’ve got to get the fly out there fast, before your quarry is gone. And because cruising trout are unpredictable, it helps to be able to change the direction of your cast while the line is in the air.

On the other hand, if they’re not alarmed, trout can be curious and will turn to the plop of a weighted nymph or the gentle settling of a dry fly. So it makes sense to appeal to the curiosity of the fish. With dries on a lake, I think that it is better to pick up and cast every minute or two, rather than just letting you fly sit. There are exceptions, though. One is when you are working a brush or tree-lined shoreline with a terrestrial and waiting for a large trout to cruise by. Fish patrol these edges as though guarding their territory, often reversing direction and coming back time after time. Get that fly out there and let it sit. Ambush that trout.

However, don’t alarm the trout by clumsy casting. Don’t let the thick forward taper of your fly line just dump on the water. Usually, a long leader ought to reach full extension and turn the flyover for a soft landing.

Also, trout don’t like boats, prams, float tubes, or the background noise made by trolling motors, particularly by the on-off switch. They don’t necessarily flee, but their caution flags go up, and they are less likely to take a fly, particularly in close. What’s close? I think it’s about 35 to 45 feet. It depends on water clarity, things such as sun elevation, cloud cover, angling pressure, and how stealthy you have been.

If I have a cast to a fish at 30 feet or closer and have another option at 45 feet, I cast to the 45-foot fish first, because I get more takes when the fly is farther away from my watercraft.

A lot of little things can influence the behavior of trout targeted by the sight-fishing angler. The angle and direction of the sun also can have a bearing on the direction from which fish will approach and take both natural insects and one’s imitation. I don’t think there’s any single way in which that happens, but there are times when you will observe a pattern. Pick up on such patterns, and you’re ahead of the game.

Sight Fishing for Bass in Still Waters

Most often, we think of trout when the subject of sight fishing comes up, but a lot of what I’ve said about sight fishing for trout in still waters applies to sight fishing for bass with a fly rod, as well. You may actually see your fish, or their presence may be given away by the moving reeds when there is no wind. As with trout, you could also find them by a V wake or a rise — with bass, most likely the splashy aftermath of the demise of an unwary frog or a bulge under a lily pad. However, sometimes those signs are as subtle as a trout’s sip of a down-wing spinner.

In addition, casting to bass that you see shades quickly into casting to targets where bass are likely to be hidden: structure such as downed timber, overhanging branches, shoreline irregularities, submerged boulders, pilings, pump intakes, or the break between a mud bank and tules. Most often, targeted fish will be right where they are supposed to be. Make your cast accurate and tight to cover.

A few years ago, John Randolph, then the editor of Fly Fisherman magazine, wrote of top-water angling for bass at Lake Mateos, one of the highly regarded Mexican bass Meccas. John said that a difference of two inches in where your fly landed could make the difference between a blowup and nothing. Two inches may be pushing it, but his point is well-taken. I calibrate and mark my floating bass taper at the point where I feel that I’m casting my best — that is, most accurately, with good turnover and a minimum of effort. It is usually about 40 feet out for me, although that depends on the rod, fly choice, and leader. It gives me a reference point so I can land my fly accurately at a distance from which the bass aren’t terrified by my presence. Make a practice cast before you go for the money and get that fly accurately to the target on your first try. Not just to that stump — go for the shaded side and bounce your bass bug off the wood.