The sight of trout, bass, stripers, or even panfish taking baitfish on the surface of a lake or savagely crashing into subsurface bait balls shows nature in its rawest form and graphically demonstrates the hard reality of aquatic food chains. I remember one snowy March day at New Melones Reservoir when we caught brown trout, rainbow trout, largemouth bass, and crappies on the same fly pattern in a cove where these fish had corralled massive schools of threadfin shad. The carnage was such that an oily sheen appeared on the surface. At the same time, smaller predator fish were preyed on by larger brethren looking for a mouthful. Baitfish attract large predators, and the kill is often on the surface. It’s enough to start anglers shaking with excitement.

Finding and fishing these events is another part of the stillwater learning curve. Sometimes it involves blind luck, but with calculation and determination it can be planned. Such occurrences usually happen at the same places in a lake year after year, but may occur earlier or later on the calendar, depending on the weather and the temperature of the water. In my foothill area, chasin’ bait is a late fall experience, but also a possibility in the winter and early spring. In other areas, it may happen at any time of the year.

Most baitfish are juveniles or fry of both native and introduced species. They are important for anglers during the post-spawn period and then throughout the year as they grow in size and change their preferred habitat. A partial list includes bass fry, kokanee fry, carp fry, sucker fry, trout fry, hatchery-reared rainbow trout, downstream steelhead and salmon smolts (whether born in the stream or reared in a hatchery), Tui chubs, Sacramento perch, white bass, yellow perch, pikeminnows, catfish young, bluegills, crappies, warmouth bass, Lahontan redsides, and sculpins.

In California, we have an impressive number of native and introduced fish species. William A. Dill and Almo J. Cordone’s History and Status of Introduced Fishes in California, 1871–1996, published in 1997, lists 53 species that have been planted in our state’s waters. Two nonnative forage fish, from the eastern United States and rivers that drain into the Gulf of Mexico, stand out: the Asian pond smelt (Hypomesus nipponensis, or wakasagi) and the threadfin shad (Dorosoma petenense). They have proliferated in many waters, migrated to others, and their liking for zooplankton, phytoplankton, and algae has completed a food-chain link between photosynthesis and trout and other predator species.

Threadfin Shad

Threadfin shad are our most common introduced forage fish. These fish were brought to California in 1953 and are found in the Colorado River system and throughout the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta (upstream of saline areas). They favor the open water of large lakes and ponds, as well as sluggish backwaters, and are usually found in the top 50 feet of the water column, using gill rakers to filter plankton of all types and detritus. They are susceptible to hard freezes and experience winter die-offs in the Delta at times. Threadfin shad group in age-class schools and ball up when attacked by predators, leaping out of the water to provide spectacular visuals.

Pond Smelt

Japanese pond smelt are our secondmost-populous introduced forage fish. Japanese pond smelt were imported in 1959 when what was then the California Department of Fish and Game was looking for another forage-food link between plankton and larger fish predators. They were originally introduced into Lake Shastina and then into other waters. The most successful experiment was in Lake Almanor. They soon found their way down the North Fork of the Feather River into Lake Oroville, where in time they displaced its threadfin shad population and wandered farther downstream into the troubled estuary that we call the Delta. Pond smelt like colder waters and spawn when temperatures hit 40 degrees in the spring. On a recent wildflower expedition to Table Mountain, near the Lake Oroville dam, my wife and I were picnicking out of the wind on the shores of Oroville’s diversion pool forebay. Diving gulls and screaming terns alerted me to a huge school of ravenous trout attacking half an acre of massed pond smelt. In my home area of Nevada County, pond smelt were planted in Lake Spaulding, high up on the Yuba River. Now they are found in downstream reservoirs such as Rollins and Scotts Flat, and, because of water transfers, in Folsom Lake, where they mix with remnant threadfin populations. In Rollins, they hang out near submerged timber stickups. These fish hybridize with the imperiled Delta smelt, further weakening the viability of that native species. In Japan, they are considered a delicacy. Look for fried wakasagi on the menu in Tokyo.

Hatchery Rainbow Trout

When rainbow trout are planted, they frequently become food for larger fish. When stocked in reservoirs up and down the state, they ring the dinner bell for predators such as largemouth bass and stripers. These predators seemingly develop an uncanny ability to know when the hatchery truck will be arriving and key into vibrations emitted by aerator compressor pumps.

I lived for many years in the Tri-Valley area near Dublin, Livermore, Pleasanton, and San Ramon and often fished Lake Del Valle. When the Thursday planting truck pulled up to the launch ramp, large bass and stripers would be there waiting. The ensuing feeding mêlée could start at dawn or anytime during overcast days, and could even be better as the sun went down, particularly on weekdays, when there were fewer anglers and less boat traffic. Farther down the lake, in the bay that spread out in front of the dam, stripers would bust threadfin shad and trout on overcast days in the late fall, winter, and spring.

Though I have never fished Castaic Lake, in Southern California, I have heard from anglers and have read a fine article in California Fly Fisher about catching record largemouths using rainbow trout imitations. We do the same on Collins Lake. These differ from thread-fin shad and pond-smelt fly patterns in that they are very large, four to eight inches long, and require 8-weight through 10-weight fly rods to cast them.

Effective Tactics and Fly Patterns

Pond smelt and threadfin shad start life as thin creatures less than an inch long. As they grow, pond smelt just continue to elongate, while threadfin shad develop a convex belly and a thin vertical profile, viewed head-on. Both grow to over four inches in length. They tend to swim in straight lines until stressed or attacked by predator fish, when they ball up and leap out of the water in frantic, erratic movements. Balling up is a common tactic with fish that have no physical defense mechanisms. Survival is based on numbers and randomness. We see this in the ocean with anchovies and with herring, a relative of the threadfin shad.

The most efficient way to target fish feeding on schools of baitfish is from a boat or other floating device, because the bait boils can occur in many different areas of a lake, and the schools of baitfish always are on the move. Stealth is important when approaching these concentrations of baitfish, whether in open water or if they have been herded and trapped in a cove or other indentation in a shoreline. Fish are wary when close to boats and do not take flies well. It is better to row or drift into range with the wind than to motor in with a gas engine or electric trolling motor. Pontoon boaters and float tubers should likewise try to disturb the water as little as possible. I’ve seen boat operators get excited and run right into the middle of the mêlée, putting fish down and angering anglers who have been out there carefully stalking their targets. Be courteous and use the Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

Stealth also involves using long leaders. For trout, I start with a supple 9-foot 3X leader and add a lighter tippet if needed. I like fluorocarbon, which is less visible underwater, sinks at a faster rate, and is more abrasion resistant. For open-water bass or stripers I go up to 1X or 0X, rarely needing a tippet. Go longer and lighter if the water is exceptionally clear. Stealth requires making lengthy casts. Denny Rickards mentions 70-foot casts when discussing this subject, so work on those casting skills. And it means fishing on overcast days, if you can, because fish are less wary and more prone to journey into the upper reaches of the water column.

Many trout anglers who chase bait have several 5-weight or 6-weight rods rigged and ready with flies appropriate for the locale. A floating line for surface imitations is essential, as well as an intermediate line and perhaps a camo sink tip with flies that work subsurface. If you are after freshwater bass or stripers, you will want to go up several rod weights, because it’s possible to hit huge fish. I always carry integrated shooting heads in several sink weights should the need arise to go deeper.

Rainbows slash through bait schools, stunning baitfish with tail slaps and wounding others with their sharp teeth. Browns approach more slowly and take their prey in a deliberate fashion, often from below. Bass or stripers can turn the surface of a cove into a froth. In fact, with all species, you will find larger fish below bait boils, picking off cripples as they flutter, rise, or fall in erratic fashion, as well as dead sinkers. Patience and a weighted fly will get you chances at these fish.

Sometimes the really big guys will wait below and take smaller predator fish that are focused on the bait frenzy. I’ve seen this with bass feeding on in open water on baitfish backed into a cove. At Lake Berryessa, I once saw a nearby boat land an 8-3/4-pound largemouth that had taken a trout that in turn had taken a small threadfin shad while trout and smaller bass ripped bait on the surface.

Retrieves vary with conditions. Dead still is one possibility, as are short one-inch or two-inch twitches and long, slow pulls. Experiment. Fish take most often on the pause and fall or the start of a slow pull. Stripers may want longer pulls and sometimes a fast retrieve that is accomplished by tucking your rod under your arm and stripping with both hands. I’ve found that a loop knot can give an enticing sideways dart to your fly when you stop the retrieve. Always point the rod down your line and even into the water to take out all slack.

Fly Patterns

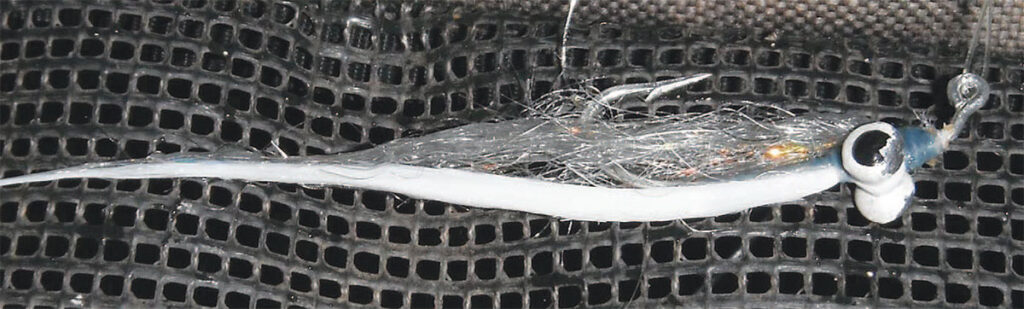

The most important keys in choosing fly patterns are fly length, then profile and color or flash, followed by animation of the fly. I carry a dedicated baitfish fly box. My patterns have evolved over the years, and many are borrowed from successful anglers. I like Hal Janssen’s Marabou Pond Smelt and his Floating Threadfin. His baitfish patterns tend to be smaller than are used in my area, though. Tom Page, who owns Reel Anglers in Grass Valley and guides for smallmouths on Scotts Flat Reservoir as well as for trout on the Yuba, has developed a dumbbell-eyed pond smelt pattern tied on a jig-style hook that is a bit larger than used at Oroville or Lake Almanor. It is equally effective on rivers and the Delta. Phil Ryan, who has fished Lake Berryessa many times, gave me several of his Small Shad patterns, tied on a size 10 hook. Trout key on small baitfish in the late fall on Berryessa and Lake Shasta. At Kelsey Bass Ranch, I found bass hitting clouds of small bass fry back in cover formed by trees and brush. I played with a few patterns without success, but Phil’s Small Shad hung two feet under a white/silver slider bass bug started taking fish.

I use this fly, which has a silver tinsel body, a white hair wing topped with a faint blue pheasant rump overwing, and a white thread head with a small black eye spot, in many situations. I fish it alone, as a trailer, or with the popper/dropper rig for trout, bass, and crappies. The fly also works behind Woolly Buggers of all colors and sizes. Other productive flies include Blaine Chockett’s Gummy Minnows in a wide range of sizes and small white-and-chartreuse Clousers. Try tying them with trans-lucent polar bear hair, if you’re lucky enough to have some. Don’t forget whitish or pearl-bodied bonefish flies such as Gotchas and Crazy Charlies. Woolly Buggers and Simi Seal Leeches in white or blue have been effective, as has the Nacimiento Shad Fly that was developed for white bass.

Chasin’ bait and the large predator fish that feed on it is a game in its own right. It’s a thrilling aspect of stillwater fly fishing. Give it a try.