The evolution of fly fishing and the staircase of progression through the years has the current state of the sport centered on a thorough understanding of aquatic insects and their interaction with the fish we seek to catch. However, I can remember the 1970s, when presentation was thought to be far more important than the fly at the end of the leader. My nymph box back then was very basic, and most of the patterns were the generic mayfly and stonefly profiles of the time, and in only a few sizes. Colors mattered, though, as in the hot-orange body of a Meng’s Regret. Today, we believe that it’s all the different little details coming together that gets the prize. We fly anglers are addicted to consuming huge amounts of in-depth information to help us when we are on the water. We’re information junkies, and when we take the time to sit back and observe a hatch, only then do we truly become one with the rhythms of the water and the fish.

Each aquatic insect is special. Each has different fascinating quirks, hatch times, and sometimes a serious cult following. We all have our favorite bugs throughout the year, and we can even be fanatics about them. I feel the great creator provided the Skwala stonefly as a way to reward trout for consuming micro mayfly nymphs and tiny midges through the dark and dreary winter months. The Skwala stone is their first big bite of protein of the new year. They can feel it in their teeth, and there has got to be some satisfaction in that.

Characteristics of the Skwala

The Skwala stone is of the family Perlodidae and can be found only in Western streams from the Rocky Mountains to the coastal mountains along the Pacific Ocean. The rivers of Northern California have sizeable populations of Skwalas, and rivers such as the lower Yuba below Englebright Dam and the Truckee have become legendary for their Skwala hatches. The size of the nymph ranges from 15 to 22 millimeters and the adult from 16 to 23 millimeters — about six-tenths to nine-tenths of an inch. The female is noticeably bigger than the male, because she must carry the eggs that will perpetuate the species. The timing of the hatch varies depending on the elevation of the river. On the lower Yuba, it usually starts at the end of December and can last until the middle of March. That’s a long time and one reason why I have chosen to make my home close by. In contrast, the hatch starts on the Truckee River sometime in February and ends around the middle of April. An angler therefore can target the hatch on the Yuba, and as it wanes, switch to the Truckee River, which means that this special hatch offers a little more than four months of fishing. Every day is truly different with this hatch, however. Warm days are best, even if it’s overcast. The number of Skwalas hatching on some days is unbelievable, while other days, the hatch is very small. As with most fly-fishing adventures, luck plays a role when you encounter a super hatch.

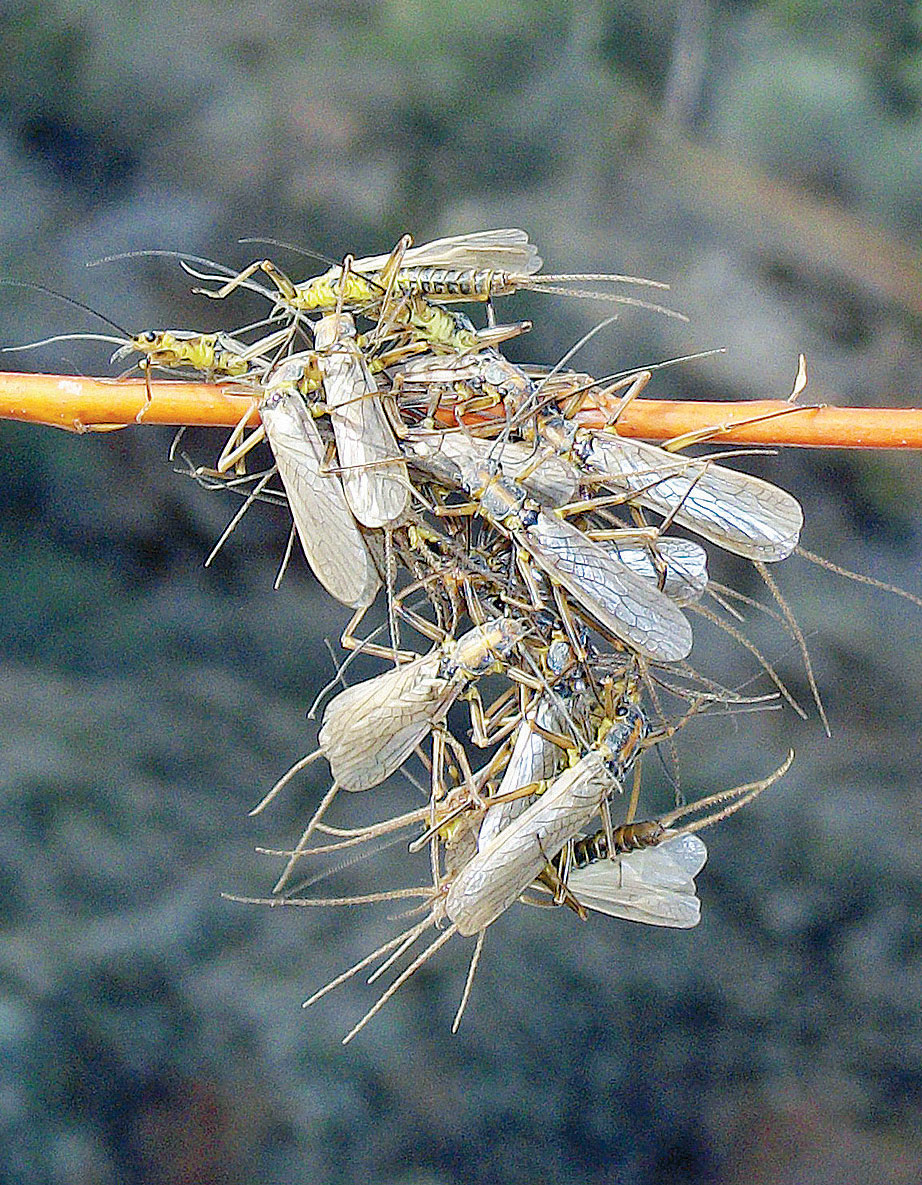

The hatch starts in the water near the banks of the Skwala’s main habitat, highly oxygenated, choppy riffles of the river with large cobbles and gravel substrate. Before emerging into an adult, these stoneflies begin staging in the slow bankside water, waiting for the perfect moment to enter into a new world. In the darkness of night, and often in the predawn hours, they crawl out onto any bank that has cobbles strewn about. They prefer rocks that have a roomy living space beneath them, with plenty of protection from birds such as the hermit thrush of lower elevations. Spacious, secure quarters also provide room for other Skwala stones to join the party. While flipping rocks on the lower Yuba, I have found orgies of newly hatched Skwalas, with males looking for females fresh out of the shuck. A scent trial of pheromones left behind by other stoneflies entices fresh crawlers out of the water to gravitate toward these concentrated areas, where they hatch, meet, and greet.

Within hours, the skin of the adult Skwala stone hardens up, and its body armor is ready for the new world above water. The rays of the sun heat the cobblestones, and during the warmest part of the day, you can find the insects sunning themselves atop river rocks, gaining enough strength to take flight or to make the long crawl to the water’s edge. Most Skwala stoneflies that make the crawl walk across the water, settle in, and go for a scenic drift. The females are off to lay their many eggs. Meanwhile, the male searches for another mate, his direction determined by the wind and the flowing water.

Like all stoneflies, Skwalas are poor flyers and are very susceptible to ending up in the drink, then in the jaws of a hungry trout. Before females lift off into the air, however, there is another place they like to meet male Skwalas. This singles spot is in the riparian habitat next to the water’s edge, and observation can reveal dozens of males swarming the branches of the willows, looking for the few females that are present.

The color of the Yuba and Truckee River Skwalas is different from their cousins in the Rocky Mountains, who wear shades of olive. Northern California’s version is a smoky yellow-olive color, viewed underneath, with dark brown and black legs, head, and a partially colored thorax of yellow-olive and black. From a tying standpoint, it’s a challenge to match the exact color, because no manufacturers produce the proper hue. Custom mixes of dubbing are the only sure way to match the color exactly. The body color of the Skwala also will change during its nearly month-long life. Fresh specimens will be brighter, and as they age, their color begins darkening and becomes riper looking. But when the trout of the Yuba and Truckee Rivers are aggressively feeding during the hatch, sometimes an imitation that is just close enough in color and size is all that is needed.

Studying their behavior while they are drifting on the water has revealed that both males and females have very twitchy legs, kicking back and forth, creating movement. Consequently, rubber legs on both the adult and nymph patterns are useful for fooling educated trout. Their movement helps to trigger strikes. Riding down the river placidly, the Skwala does not beat its wings and remains quiet in every way, except for those highly active legs. To the untrained eye, the bugs look like small twigs floating by as you work the water. But if you slow down and keep looking, the bugs are there. With more time on the water looking for clues, your eyes become trained, enabling you to pick up the minor subtleties in aquatic insect behavior.

Lower Yuba Tips

When it comes to the actual fishing, two methods dominate: nymphing and fishing dry flies. Fishing indicator rigs while drifting on the lower Yuba can be snooze-inducing, but short-line high-sticking the pocket water on the Truckee gets me excited. Unfortunately, high-stick nymphing without an indicator is an art that is slowly being lost. It’s not easy, and it requires your full attention while watching your leader for any unnatural movement.

For three months during the hatch of 2014 on the lower Yuba, though, I never tied on a nymph. Dry-fly presentations were not only very effective, but brought some of the best fishing of the year. Stalking trout, seeking rise forms, and casting to sippers in the back eddies is absolutely the best. Fishing the Skwala adult on the surface is a passion that flows through my veins. It’s a challenging game, yet rewarding, when you finally hook an elusive bank feeder after dozens of drifts.

The lower Yuba River offers the best winter dry-fly fishing in the Golden State.

In addition to the Skwalas, there can be Pale Morning Duns and Blue-Winged Olive mayflies hatching at the same time. The winter air temperatures of the low-elevation lower Yuba, set among the rolling foothills of the Sierra, are mild, and if the coming winter is like the last one we had, short-sleeved shirts and a little sweat on the brow could be the norm.

The lower Yuba is a tailwater fishery, with flows subject to change, especially with the onslaught of rain. Englebright Dam is a flood-control dam, and at any time during the rainy season, high volumes may be released. These releases can blow out the river, and poor water clarity can stop the fishing for a few days. But the river comes back into shape rather quickly. Many guides and hard-core anglers actually like it when the lower Yuba has a slight stain. Ultraclear water makes for spooky, nervous trout, and during those conditions, you had better bring your A game and have a good plan of attack. The complex shifting seams of the side waters on this river make presentations very difficult, and the more line you have out, the more there is microdrag on your fly. Drag-free presentations are a must here. Every day spent on the lower Yuba teaches a new lesson, and fly fishers who apply themselves to what the river can teach will walk away better anglers.

Truckee Tips

The Truckee River is a completely different watershed. While the same nymphing and dry-fly tactics apply here as on the Yuba, the trout are to be found in the many different habitats that characterize this river: in pocket water, pools, deep runs, riffles, canyon water, and unique side-water structures. The Truckee reminds me of a smaller version of the upper Madison River below Raynolds Pass Bridge, where large brown and rainbow trout make their home in the slicks of the rock gardens among the sweeping flows. Slowing down your pace even further and dissecting every nook and cranny is the smart way to fish this river effectively, because you never know where a Skwala eater will be hiding. And unlike the lower Yuba, which has a fairly limited amount of water to fish, the Truckee has countless miles that stretch from the town of Truckee all the way to Reno and that continue downstream to the east. Just as dam releases affect the lower Yuba, however, snowmelt and high, unpredictable flows also affect the Truckee, and the slower water becomes an important target during such times.

Angling Tactics and Flies

Fishing the Skwala hatch is not specialized in any way. Reading the water and keeping your head on a swivel, looking for rise forms, are important. For nymphing, indicator rigs are a highly productive way to fish, especially on the lower Yuba. There are so many different ways to set up your rig that it comes down to personal preference. You don’t really need a tapered leader, and many guides run straight 3X tippet 5 feet down from the indicator to the first fly, then add 24 inches of 4X for a dropper to a smaller nymph. Depending on the flows, add different amounts of split shot 12 inches above the first fly. Heavier flows require more lead. Mending line to get a drag-free drift is of great importance when indicator nymphing, whether you are drifting your flies upstream or downstream, and mending often is the difference between success and failure.

The art of short-line high sticking is more about technique than about equipment. I cannot stress enough how productive this technique is when fishing subsurface. This style was taught to me by my father at a very young age. It’s simple in theory, but the concentration required is taxing. A good leader formula for shortline nymphing is 5 feet of 0X mono (figure around 10 to 12-pound test) in a color such as blue or, my personal favorite, moss green. Next tie on 4 to 5 feet of clear 2X or 3X to the first fly. The knot that connects the leader to your tippet acts as a visual depth gauge so you can calculate just how deep your fly is drifting. Finally, 2 feet of 3X to 4X to your dropper fly rounds out the completed leader. Lob casts are best, because your flies enter the water vertically, with some velocity. This allows the flies to punch through the surface. When your flies reach the depth you are targeting, lift the rod so the leader is stretched out with zero slack. You want a tight leash to your flies while maintaining a drag-free drift. The way I fish, the rod tip follows the flies during the drift, and if the leader stops, moves upstream, or twitches, it’s time to set the hook with a sweeping motion downstream. This is where the different-colored mono on the upper leader comes into play, allowing you to see any odd or irregular movements that occur. Being proficient with short-line high-stick nymphing takes lots of practice, and Zen masters of this game often know when to set the hook on pure instinct alone.

When it comes to fishing the dry flies during a Skwala hatch, more often than not, a perfect presentation is almost always needed, especially on the lower Yuba, because the rainbows there are highly educated. When using a Skwala dry fly as a searching pattern, I cast upstream, starting close to the bank, then fan casting farther out. Once I cover a small section of river, I walk upstream 20 feet and cover another section. However, when you observe a working fish in a feeding lane, the best way to present the fly is to cast downstream, land your fly in the lane, then feed your line down the currents to your intended destination. The hardest thing to judge when making this kind of presentation is the fine line between having too much slack out to set the hook and having not enough to prevent drag. The fly must drift without drag, not some of the time, but all of the time.

The lower Yuba is often fished from a drift boat, and local guide Tom Page, owner of the Reel Anglers fly shop in Grass Valley, suggests that when the water is low and clear, casts from a boat should be on the long side and spot on. He likes to keep his boat 30 feet off the bank and have his anglers cast 45 degrees downstream, landing the fly a few feet away from the bank. His preferred presentation is what he calls a “wiggle cast,” which involves throwing a controlled amount of slack into the line so your presentation is not affected by drag in the many microcurrents. Tom’s leader formula for drift fishing a Skwala dry begins with a 9-foot leader tapered to 3X, joined with 3 feet of 4X to the fly. This helps in getting a drag-free drift. During the past winter, he noted that in the low, clear flows, smaller hook sizes brought better results, even though the real bug was bigger.

The patterns for fishing the Skwala hatch can be as simple or sophisticated as you like. For the nymphs, a Jimmy Legs, size 8 to 10, in a mottled brown and burnt yellow is a favorite. Other subsurface flies could include Mercer’s Tungsten Skwala Nymph and Hogan’s Yuba Rubberlegs Stone. A wide variety of dry-fly patterns can imitate adult Skwalas. The tried-and-true Stimulator does a good job when the trout are hungry and not concerned with details. My favorite pattern is the Unit Skwala, a pattern from the Bitterroot River in Montana that was introduced to me by a close friend. This fly has an extended foam body, rubber legs, and a bullet head created from moose hair. Tom Page’s Yuba Skwala is another deadly fly. It was created after years of trial and error. Adding neon-colored foam or poly yarn on top of any Skwala dry-fly pattern will help you keep it in sight, because most patterns are very dark and become invisible when on the water. As the days become shorter and fall turns to winter, most of us put away the fishing gear. But the sun still shines on some days, and a Skwala hatch is awaiting during the warmest time of day. That’s good enough a reason to dust off the rod, and seek cobbled banks, solitude, adventure, and the hope of a rising trout.