I recently posted images of my Jig Hook Flashtail Whistler on my Facebook page, showing it and a few of the striped bass and largemouth bass it had taken. The pictures garnered a number of likes and comments, one of which struck home with me. The gist of the comment was that while the Whistler is still one of the most relevant classics, very popular worldwide for a huge variety of species in both fresh and salt water, most fly anglers today wouldn’t know who originated it or its history. Many other classics fall into the same category. Accordingly, I thought I’d write the history of the Whistler, a fly of which I’m very proud and one that holds a prominent place in my selection of productive flies.

I developed the Whistler in 1964. It was designed to take striped bass in San Francisco Bay, and it was not created to imitate any particular baitfish. Instead, I “engineered” the fly to mimic the look and action of a lead-head bucktail jig, one of the most productive and versatile fish-catching lures ever devised. The bucktail jig emulates a huge variety of baitfish species in both fresh and salt water, mostly the deeper-bodied baitfishes, and the Whistler does, as well.

The local gear guys were kicking our asses with lead-head jigs, all-white and red-and-white versions. Our simplistic bucktail patterns of the era just didn’t work as well.

The first pattern I came up with in response might well have been the first “reverse-tied” bucktail, a technique best known today thanks to Keith Fulsher’s Thunder Creek streamers, and it looked exactly like a red-and-white lead-head bucktail jig. The problem was, it didn’t have much action, although it caught fish.

I kept experimenting. I ended up using an extrashort-shank live-bait hook to keep all the weight forward to enhance the dipping and diving action that a bucktail jig has and to eliminate fouling of the bucktail wing when being cast.

I added bead-chain eyes for weight and to help the jigging action. Another benefit was more underwater noise and the ability to push more water. The eyes actually whistled when the fly was cast, too, and that’s how the fly got its name.

I included a narrow red chenille collar to simulate gills, also to add more frontal weight, and a three-hackle collar between the chenille and the bead-chain eyes. The hackles were a mix of soft and stiff barbs, which provided extra action and pushed more water. Some people have tied the collar with rabbit, but rabbit does not push water — it lies down flat when wet.

In the early years, through the mid-1970s, the Whistler was always tied “in the round,” often with grizzly feather flanks. Thus, it always looked “right” no matter how the fly turned or twisted in the water. In other words, there was no topping of a contrasting color.

The first Whistler was all white with a red bucktail lateral stripe — a white Mickey Finn Whistler. Next came the red/white/grizzly, yellow/red/grizzly, and black/grizzly, ending up with more than 20 color variations. All had names that addressed their color pattern: Black Whistler Grizzly, White Whistler Grizzly, and so on. In 1971, I started tying them with flashtails, using 1/64-inch Mylar strips. I was inspired by a lead-head jig that Mark Sosin was using to slay the snook. He was outfishing me horribly. I went back to camp, tied a Whistler with a flashtail, exactly as I do today, and the next day I pounded the snook and Mark, too. Today, I use various colors of Flashabou in the original saltwater size. My favorite tail color is a 50-50 blend of pearl and silver Flashabou, although I’ve been having phenomenal results the last few years with a tail of only pearl Flashabou.

In the early 1970s, I met Ed Given while fishing on San Francisco Bay. A friend and I were slamming the stripers, and Ed rowed over in his little pram, introduced himself, and asked to see the fly I was using. It was a Whistler. Later, he adapted most of the Whistler components into a fly he called a Night Crawler. It was similar to Russ Chatham’s Black Phantom fly. I later renamed Ed’s fly the Barred ’n’ Black.

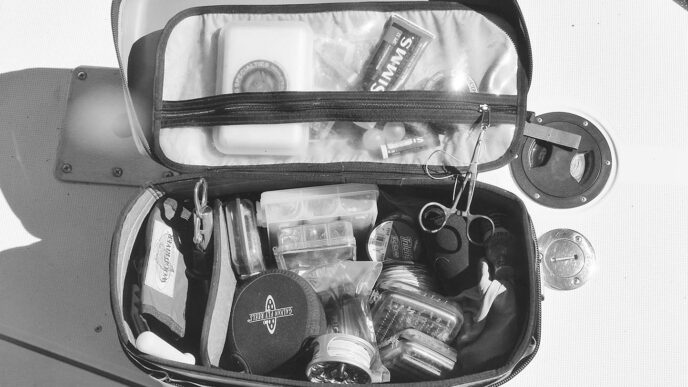

Today, I tie the Flashtail Whistler in many color variations, and while I still tie them on short-shank conventional J hooks, I now tie most of them on a 60-degree jig hook, the Targus TAR9413, which is identical to the Fly Shop’s FS5444. I use both Spirit River Real Eyes and bead chain for the eyes. Bead chain is still great, but it doesn’t look as good, although if I want to push a lot of water, I tie a few using 1/4-inch bead chain. I call these the Big-Eyed Whistlers. All of my Whistlers today are tied as flashtails. For non-tyers, they are available for purchase from Umpqua dealers in both standard J-hook and jig-hook versions.

For years, I resisted using synthetic materials for tying my Whistlers, opting only for bucktail and saddle hackles for the main components. Today, I use a lot of synthetic hair for the wing. My favorite material is called Flash’N Slinky, produced by H2O. This is basically a wig material with some added flash and is slightly kinky, instead of straight. It looks good, moves well, and doesn’t make rat’s nests as badly as some other types of synthetic hair. The fish just stomp it.

While the Whistler was originally designed to take West Coast stripers, it takes many other species, as well. It is the top jungle-river tarpon fly in Central America, for example, and it is also the number-one peacock bass fly in Brazil. Northern pike love the fly. More than 400 species of fish, worldwide, have been taken on Whistlers, including several world records. It remains one of the most versatile styles ever created.

In 1964, there was nothing around like it — nothing nearly as sophisticated for doing what it was designed to do. In Streamers and Bucktails: The Big Fish Flies, Joseph D. Bates, Jr., said the Whistler might well be the greatest fly design ever created. Well, I don’t know about that, but it sure turned out to be a damned good fly.