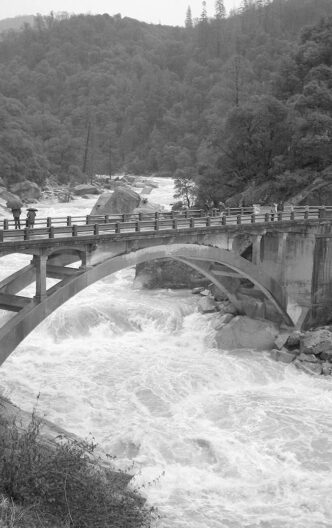

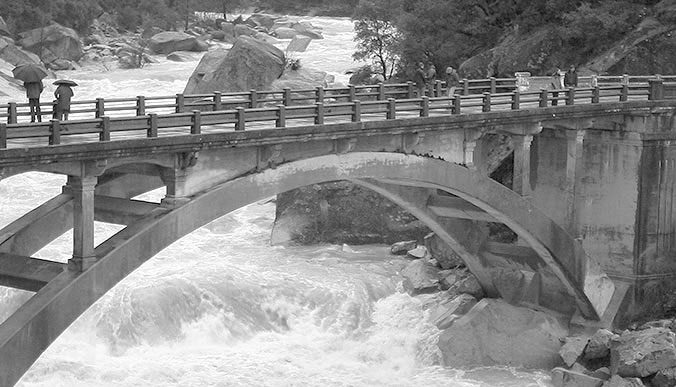

I learned to fly fish growing up in Paradise — not figuratively, but literally. Summer vacation was my favorite time in my hometown of Paradise, which is located on a ridge just above Chico, California, between two tumbling freestone streams, Butte Creek and the Feather River. I would ride my Stingray bicycle to the rim of the ridge and hike down into the canyon to test my latest fly creations on the native rainbow trout. Often, I wouldn’t return until well after adult dark (the time my mother called for me) and would fish until kid dark, when the fish bit best and when I could no longer see my fly — or much of anything else.

These formative years shaped the way I fish and my fly selection to this day. The steep-walled freestones had a variety of water types and a wide diversity of insect life. Hatch matching had not come into vogue, and if it had, I might have needed to carry a backpack full of flies. I kept my attire and equipment simple and efficient, but most importantly, effective. I wore jeans until the knees blew out, then cutoffs, a T-shirt, and high-top Converse shoes (black ones, preferably) with carpet glued on the bottoms, all topped off with a Giants baseball cap. I carried a single box of flies (mostly dries), some Mucilin floatant, a few split shot, and a spare leader in a shoulder bag that doubled as a creel.

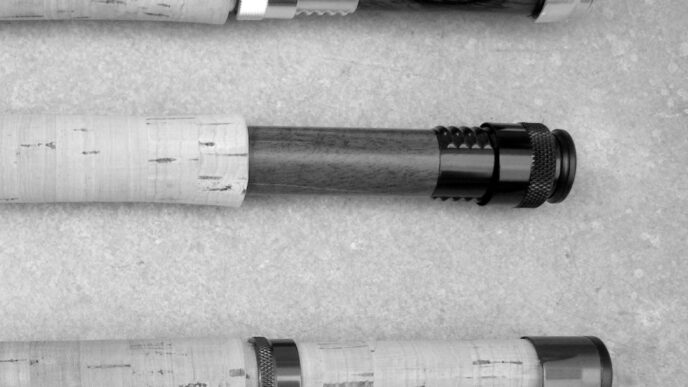

I learned that a well-placed and well-drifted fly will work better than the perfect fly poorly placed. My fishing and tying have evolved since that time, but some things remain the same. The rods, lines, and equipment I carry fifty years later allow me to use a variety of techniques from the top to the bottom of the water column, and the flies that are in my boxes are versatile patterns that help meet the uncertainties provided by the natural world I am forever trying to understand better.

Up to 90 percent of the trout I catch each summer come on 10 patterns that I carry year round. The dry flies are the Humpy and Parachute Adams; the nymphs include the Bird’s Nest, Pheasant Tail, Prince, Copper John, Micromay, and Rubberlegs. I also carry soft hackles and a streamer — a Woolly Bugger. The other fish come on specialty flies that I carry seasonally. In this review, I discuss 5 patterns. Three can be found in my box year-round: the Humpy, soft hackles, and the Bird’s Nest. Two I use seasonally: the Iron Sally and the Fox Poopah. I will detail why I have chosen these flies and why and how I fish them. None of this is meant as a prescription, but I hope it will stimulate your thinking about how you most enjoy fishing and help you select flies that add to the pleasure of your pursuit.

The Skinny Humpy (or Hatchmaster)

If I were forced to fish only one dryfly pattern, the Humpy in a sparse tie would be my choice. I have been fishing it for as long as I can remember. While it is a popular fast-water attractor pattern that floats high on such rough-and-tumble freestones as the McCloud, Pit, and upper Sacramento, I also use it to represent a host of different insects, including all stages of mayflies, caddisflies, stoneflies, and even terrestrials.

My affection for this pattern was sealed for me a few seasons ago when Dick Galland, who owned Clearwater House on Hat Creek, held up a size 18 Hatchmaster (Dave Lambroughton’s knockoff of the Humpy) and remarked, “If this fly doesn’t work for you, it is not because it isn’t the correct pattern.” Hat Creek is known for its fussy fish, and the selective feeders I had targeted for the evening hatch were all that and more. But as usual, Dick’s advice was spot-on. The fly, tied on a long leader and 7X tippet, fooled some of the best of them, including a 20-plus-inch brown sipping emergers tight to the far bank.

While this pattern has proved its worth with challenging trophy trout on famous technical rivers such as Hat Creek, the Fall River, the Rising River, Silver Creek, the Henrys Fork, the Firehole, the Big Horn, and Slough Creek, the most fun I have with it is when angling for eager, small trout on a warm summer day, wet wading the kind of tiny creeks and canyon water I first fished as a kid.

Humpy

Hook: Tiemco 100, size 8 to 18

Thread: 8/0 or 6/0 Uni-Thread, color of body

Tail: Moose or elk hair

Shellback: Elk hair pulled over thread to form wing

Body: Uni-Thread

Wing: Elk hair from shellback

Hackle: Mixed brown and grizzly rooster

I typically attach a size 14 or 16 Humpy to a 6-foot or 7-foot 5X leader and fish a 3-weight or 4-weight rod (preferably bamboo) and a floating line to match. Walking into an out-of-the way place with a few spare flies stuck in my hat, I enjoy the solitude or, better yet, the companionship of a good fishing friend. I have found this style of angling to be soothing to the soul, because it offers minimal technical distractions and returns me to my roots, allowing me to experience both the natural world and the magic that fly fishing offers.

I carry sparsely tied Humpies in my box year-round. My favorites feature yellow and rusty orange thread bodies in sizes 8 through 18, as well as dark olive or black bodies in sizes 16 and 18. The versatility of the Humpy offers the opportunity to carry one pattern to solve fishing challenges throughout the season. I use large Humpies to supplement my patterns that imitate Salmonflies and Golden Stones in the late spring and early summer. As these hatches progress on popular public waters, trout begin to reject standard stonefly patterns, so throwing a large orange or yellow Humpy into fast-moving, choppy runs to represent a fluttering bug can get fish to commit when the more accurate pattern they’ve already seen might not.

The large Humpies stay in my box throughout the summer to serve as attractor dries, the yellow ones perhaps taken as small grasshoppers. More often, they serve as ideal high-floating attractor dry flies to present nymph droppers off the bend of the hook. For short drifts, particularly when fishing pocket water, I often tie on a fast-sinking wired-bodied fly such as a Copper John, Copper Caddis, or an Iron Sally (more about this fly later) with 2 feet of tippet off the hook bend. This can be a very enjoyable and productive method when there is little or no hatch activity or surface action. If there are emerging insects, I might opt for a tungsten beadhead dropper that better imitates the nymphs and emergers. The evening hatches of summer are a thing to be savored, and the Humpies in my box most often serve as my first option. Early in the summer, a size 14 or 16 Humpy in rusty orange is one of my most productive flies during the hatch of Pink Alberts (Epeorus) that we experience on the upper Sacramento and McCloud. Later in the season, hatches of Pale Evening Duns (Heptagenia) are matched with size 14 to 18 yellow Humpies tied to long, light leaders. This fishing sometimes gets a bit technical, especially with fish that see significant fishing pressure. I sometimes clip the bottom hackle so that it is even with the point of the hook (thorax style). Also, if cut shorter, the fly will sit low like a “cripple.” Andy Burk once noticed the effectiveness of a torn-up, partially submerged Humpy and substituted a body of marabou to create an original cripple pattern that remains effective today. (See the March/April 2011 issue of California Fly Fisher for my description of fishing Andy’s Green Drake Cripple.) If the Humpy doesn’t entice a grab, I often hang a soft hackle off the bend as a dropper.

Soft Hackles

If you’ve read some of my previous articles, you’re familiar with my fondness for soft hackles. Though they have a place in my box year-round, summertime is when I fish soft hackles the most often. In the January/February 2011 issue of California Fly Fisher, I discussed the merits of the Pheasant Tail Soft Hackle, which I carry year-round. I add additional patterns to the box for the summer, including the Partridge and Yellow, Partridge and Orange, Partridge and Olive, and Ginger and Yellow. I enjoy tying these simple patterns in a traditional manner, using Pearsall’s silk in my bobbin rather than more modern threads. It’s a way to feel part of fly-fishing history.

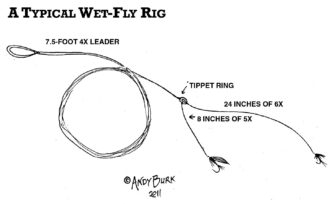

For fishing soft hackles, the method I use least is the traditional approach of swinging a brace of flies. Instead, as I mentioned, one of my favorite methods is to hang soft hackles off dry flies for difficult fish during hatches. My dry fly will most often be a Humpy or a Parachute Adams, particularly when fishing freestone streams. When the Parachute Adams or Skinny Humpy gets bumped and refused, I take that as a signal to attach a foot to 18 inches of 5X or 6X tippet off the bend to a soft hackle. Soft hackles by design produce movement and the illusion of life.

In the especially challenging situations that occur on California spring creeks such as Hat Creek or the Fall River, I might drop to a 7X tippet and pick out a dry that floats well, but that represents the hatching mayfly duns as accurately as I can manage. The dry fly allows my failing eyes to track the soft hackle as it sits flat in the film, a juicy, vulnerable cripple or spinner for savvy big trout. You need to observe closely, because takes can be quite subtle.

It also serves best to use a soft set on the light tippet, because the fish can often be larger than anticipated.

Soft Hackle

Hook: Tiemco 3769, size 14 to 20

Thread: Pearsall’s silk

Body: Pearsall’s silk

Thorax: Hare’s mask dubbing, color to match thread

Hackle: Partridge or hen hackle

Head: Pearsall’s silk

I most often dress soft hackles with Dry Shake to float them, and when that doesn’t draw hits, I wet the fly and tippet and let them sink a bit into the film. Fish prefer to feed just beneath the surface more often than I might wish. The Humpy, Parachute Adams, or match-thehatch dry gets treated with liquid floatant, as does the leader from the fly line to the tippet. I leave the tippet untreated so it sits in, rather than on the surface. I then use only Dry Shake on the flies. If they continue to sink, I retreat the leader with liquid floatant and the flies with Dry Shake. After several fish chew on the dry fly, it sometimes will continue to sink. When this occurs, I’ve found it to be most efficient just to tie on a fresh fly, rather than fuss with liquid floatant.

Soft hackles also serve regular duty on my nymphing rigs, both with and without an indicator. Along with Bird’s Nests, they are my first choice when selecting unbeaded nymphs. Fished as nymphs, soft hackles do a very credible job of imitating emerging mayflies, caddisflies, and midges, as well as crippled emergers and spent adults. Again, their movement, particularly in the slower-moving flows of summer, breathes life into the presentation, and they get grabbed when more traditional, lifeless nymphs do not. At the end of the drift, I almost always allow the flies to lift up off the bottom, which draws a surprising number of strikes, and in slow flows I retrieve them in short strips as they swing.

I do sometimes swing soft hackles, but rarely in the prescribed manner. Most often, I swing to fish that I have seen move on the surface, but whose rise form reveals they are taking subsurface. (The lack of a bubble is one sign.) I like to quarter the cast downstream above the fish, as if I were dry-fly fishing, and present the fly greased-line style, alternately feeding line and swinging to keep in touch with the fly. This technique can fool very wary fish on challenging waters, including big browns on the McCloud, Trinity, and Truckee and rainbows on the Fall River, Hat Creek, and lower Sacramento. Steelhead also have fallen prey to it.

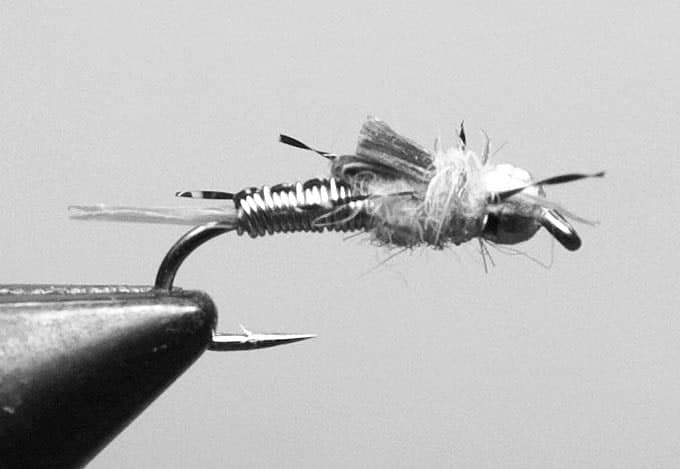

Morrish’s Iron Sally

When Little Yellow Sallies are hatching, which they do throughout a good part of the summer where I live and fish, Ken Morrish’s Iron Sally replaces my Copper Johns. Iron Sallies are constructed in a similar manner, with bead heads and wire bodies. They sink quickly and spend a good deal of time where the fish like most to eat.

On my nymphing rigs, I place a size 14 or 16 Iron Sally closest to my split shot, with another nymph the same size or smaller trailing off the hook bend. The Iron Sally is also my go-to fly when fishing a dry fly and dropper in pocket water during the summer, again because of its sink rate. Iron Sallies can be tied or purchased with tungsten beads, which further increase their sink rate, but the weight must be compensated with a really buoyant dry fly. It is important to provide enough drop for the fly to get grabbed — 20 to 30 inches of drop is usually about right.

Morrish’s Iron Sally

Hook: Tiemco 5262, size 14 to 16

Bead: Gold brass (tungsten optional)

Thread: Gold 8/0 Uni-Thread

Tail: Gold goose biots

Body: Gold wire and black Krystal Flash

Legs: Black Krystal Flash

Wing case: Turkey tail

Thorax: Gold dubbing

Antennae: Gold goose biots

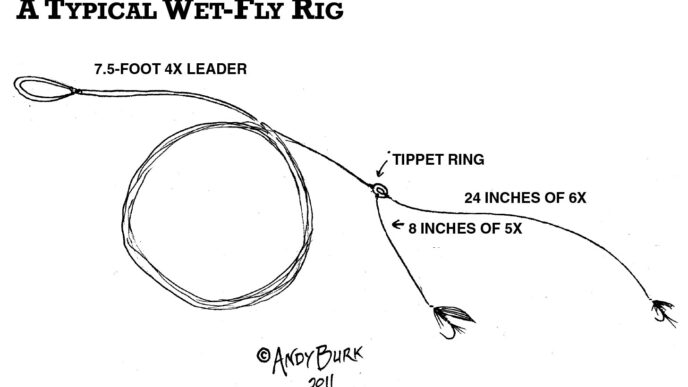

My very favorite way to fish Iron Sallies is when the water I am targeting features longer runs, glides, slots, or glassy water such as you find on the Pit, upper Sacramento, Feather, or particularly Hat Creek or the McCloud — water where stealth is key. I rig a large Humpy or Parachute Adams, size 8 to 12, in a hoppercopper-dropper configuration by adding an additional dropper below my dry-anddropper rig, most often a caddis or mayfly nymph. The key to avoiding tangles with this rig is to keep the distance between your fly line and the dry fly short — a leader of 5 to 7 feet to the dry fly works best, with twenty to thirty inches between the dry and the dropper. The distance between the two nymph droppers is also critical — 9 to 15 inches apart will allow the flies to turn over together, rather than tumbling and tangling. To avoid tangles, it is wisest to start with shorter leaders and tippet lengths.

Try casting a short line until you gain some experience controlling the open loop required when fishing this rig. To cover water as you are learning this technique, you might try moving to a new position whenever possible, rather than lengthening line. With the hopper-copper-dropper rig, classic runs that are typically nymphed with indicators during the high flows of the spring can be fished effectively with much less chance of spooking fish in the low, clear flows of the summer. (The rig works like magic during the October Caddis hatch in the fall, as well.) Most often, grabs come on the nymphs, but I have been pleasantly surprised by the number of fish, particularly larger ones, that are willing to eat my “bobber fly.”

Skinny Bird’s Nest

If I had to fish with only one fly, the Bird’s Nest tied sparsely would be it. I fish it with and without bead heads as my allpurpose, go-to nymph, emerger, cripple, scud, drowned ant — you name it. I fish it most in the tumbling freestone streams that I frequent, but it has also served me well on tailwaters, spring creeks, and still waters across the West. The reason I rely on it is that it has helped me to solve more fishing problems than any other fly I have ever carried.

I have been fishing this pattern for nearly fifty years, but a little over thirty years ago, Paradise guide Tom Peppas demonstrated his Bird’s Nest tie at a meeting of the Chico Area Fly Fishing Club I attended. His tie, like mine, was considerably sparser than commercial ties, both then and now. Unlike me, he used wood duck flank, rather than mallard flank, for the hackle legs. He also flared the wood duck, with an effect that circled the fly much like a soft hackle, a style I have incorporated ever since. For non-tyers, I am sorry to say I have yet to find a commercial tie that fishes half as well.

Bird’s Nest

Hook: Tiemco 3761, size 12 to 18

Bead: Gold, copper, or black/nickel (tungsten optional)

Thread: 8/0 Uni-Tread, color to match dubbing

Tail: Wood duck flank fibers

Body: Hare’s mask dubbing (guard hair removed)

Rib: Gold, copper, or silver wire

Wing/Legs: Wood duck flank, flared

Thorax: Hare’s mask Dubbing (with guard hairs)

The Bird’s Nest is my go-to fly whenever I encounter emerging caddisflies, which is frequently, during the summer months in Northern California. I carry it in sizes 12 to 18 in the standard tan color with a gold bead, in an olive-brown color with a copper bead, and in black with a black/nickel-colored bead. Most often I fish the beaded pattern as the upper fly in a tandem nymphing rig, with my trailer fly nearly always a Pheasant Tail or Micromay Nymph when prospecting during nonhatch periods. It’s also a go-to fly tied with a tungsten bead on dry-and-dropper rigs and as the point fly on a hopper-copper-dropper rig. I sometimes switch to an unbeaded Bird’s Nest as the dropper when emergers are present or when fishing soft or otherwise quiet water.

One of the strike triggers present in this fly is the spiky dubbing, which traps air bubbles, simulating the gas-filled exoskeleton of mergers. This effect can be enhanced as suggested by Ralph Cutter by dipping the fly in Dry Shake, as you would a dry fly.

The Bird’s Nest has been the most effective fly I have used on the swing for trout. I swing it up at the end of the drift when I’m nymphing runs and when dredging deep water, but also swing it on the surface to active risers, as I described with soft hackles. If I am swinging a small streamer or leech pattern, I often tie on a Bird’s Nest or soft hackle and swing and retrieve them in tandem. This can be very effective on technical spring creeks, as well as on still waters such as Manzanita Lake, which is known for its educated trophy trout. I have had considerable success when retrieving it as an emerging Callibaetis, when dead drifting it as an emerger, and even when floating it as a cripple dropper off a parachute dry.

Fox Poopah

I would be remiss if I did not include Tim Fox’s incredible fly, the Fox Poopah, in a review of North State summer flies. I have witnessed a parade of flies that have had their day on the lower Sacramento River, including the Bird’s Nest, LaFontaine’s Deep and Emergent Sparkle Pupas, Mercer’s Z-Wing Caddis, and Pettis’s Pulsator. The Fox Poopah has outfished them all and has stood the test of time.

There is no fly that matches its performance when imitating the prolific summer Hydropsyche caddis hatch that starts on the lower Sacramento in the spring and continues well into the fall. Defying logic, the fly continues to be the top producer, despite the fact that most anglers now use it most of the time. One would think that selective trophy trout would discover the fake and become immune. The only explanation that I can offer is that it simply imitates the natural so well that they are unable to refuse it.

Fox Poopah

Hook: Tiemco 2312, size 12 to 16

Bead: Copper (optional)

Thread: Brown 6/0 Uni-Thread

Underbody: Pearl Flashabou

Body: Tan (peach colored) vernille

Rib: Fine copper wire

Legs: Brown hen back

Antennae: Wood Duck flank fibers

Thorax: Brown ostrich herl

I have fished the Fox Poopah effectively for summer caddis hatches on other local rivers, including the McCloud, Pit, upper Sacramento, Feather, Yuba, and Hat Creek, and while the results may not be quite as dramatic as on the lower Sacramento, the pattern has many times been the difference between a fair day and an excellent one. I carry the tan version (almost a peach color) in sizes 12 to 16, with the 14s receiving the most work.

When the grab is on, I often dead drift Fox Poopahs under an indicator in tandem with a beadhead upper fly and an unbeaded fly hung off the bend. The fish grab this fly hard, so I often will fish a bit heavier tippet — 3X to the first fly and 4X to the trailer. The grabs can be wrenching when you let the flies lift up and swing at the end of the drift. In addition to tan, I tie this pattern in olive, green, bright (“insect”) green, and black, which I carry mostly for the spring caddis hatch in sizes 14 to 18.

Try some of the flies I have suggested, or, if you fish them already, try fishing them in one of the new ways I’ve mentioned. I hope I have stimulated your thinking about the fly fishing you most enjoy and how you might best fill your box with flies that enhance your Northern California fly-fishing experience.