Fly fishing is a game of confidence. That’s not the same thing as a confidence game, although there is of course an element of that, too. (We con fish into taking imitations for naturals, and we add a couple of inches to the description of every fish we catch, even if we’re just conning ourselves). But confidence matters. We are told, we believe, and experience even proves that a fly fished with confidence catches more fish. Hence the “go-to fly.”

This is the fly that we’ll have tied on our tippet as we wade into the stream or surf or sally forth onto the lake or river, warmly believing that on any cast now, maybe even the first, a fish will take the fly — “with confidence!” — while choirs of angels sing “Hallelujah,” small woodland creatures gather round and applaud, the sun turns into a smiley face, and pigs, as is their wont whenever we go a-fishing, fly. Or it can be the fly we go to when there’s no obvious feeding activity and we’re trying to at least entice a bite and maybe even figure out what’s going on under the surface — the fly that we have confidence will make fish materialize out of nowhere and reveal the mysteries of the deep. The go-to fly is thus the opposite of the dreaded “fly of last resort,” the pattern tried in desperation when the go-to fly has let us down, as have boxes full of otherwise perfectly good patterns, although sometimes it’s the same fly, the paradoxes of fly fishing being what they are.

Most people have a go-to fly. It is very much a personal kind of thing, a conclusion arrived at by the peculiar conjunction of trial and error, tradition, sheer randomness, and grace that characterizes fly fishing. For some, it’s an ant or beetle imitation, fished when nothing is hatching or perhaps even in the midst of a blizzard hatch, while for others, it’s the ol’ reliable Adams or Clouser Minnow. And of course, some fish the California surf, while others fish backcountry streams high in the Sierra or bass waters in the lowlands, so their personal choices also reflect where and how they angle.

California Fly Fisher asked a number of its contributors to discuss their go-to flies. See how they compare with yours.

Richard Alden Bean, contributing editor, California Fly Fisher

For all of my small-pond angling and much of the bass fishing I do on larger lakes, my starting fly, especially when there’s no surface activity, is a worm imitation. Actually, it is a worm imitation imitation: after all, what I’m really imitating is the plastic worm that has proven itself over decades of bass angling as the go-to lure for bass anglers everywhere. Who am I to challenge that superior performance?

Seriously, a worm fly, constructed of any slinky, fluid material (my favorite design is crafted from strips of rabbit fur), mimics a living creature better than anything else I know. A worm fly that’s anywhere from four to as much as eight or nine inches long will draw hits under almost all circumstances. The slender body/tail moves with the slightest twitch of the line or rod tip, and it reacts in any current just like a living creature. What do the bass think it is? Who cares? It works.

Bill Carnazzo, fly-fishing guide and contributing editor, California Fly Fisher

I feel naked if I arrive at the trout stream without a good supply of a bug I’ll just call the “Scary Starling.” It’s simple: no tail, a wrapped pheasant tail body ribbed with fine gold or copper wire, a rather full peacock herl thorax, and a starling feather wrapped in front of the peacock, soft-hackle style, all on a standard nymph hook such as a TMC 3761BL, sizes 16 and 14.

Yes, it’s a simple soft-hackle fly. I generally tie it on as a “stinger” using about 12 to 16 inches of 5X fluorocarbon lashed to the bend of the bottom nymph in my short-line nymphing rig. I fish it shortline style until it passes my position, then let the rig swing below me, using a Liesenring Lift type of motion at the very end. If that doesn’t work, I’ll simply swing the fly on a long leader, using a small split shot when necessary to get the fly down.

Nick Curcione, angling writer

Being a saltwater guy, I would go with a chartreuse-and-white Clouser. This has been my go-to fly for stripers. Tied in size 1 to 6, it’s great for schoolies, but I’ve also taken bonefish and redfish with it. In freshwater, it ’s done the trick on pike, pickerel, and largemouths. In the surf (both Northern and Southern California), I’ve taken barred surfperch, yellowfin croakers, and halibut. Lots of spotted bass have fallen for it in Newport and San Diego Bays.

Lisa Cutter, fly-fishing instructor and artist

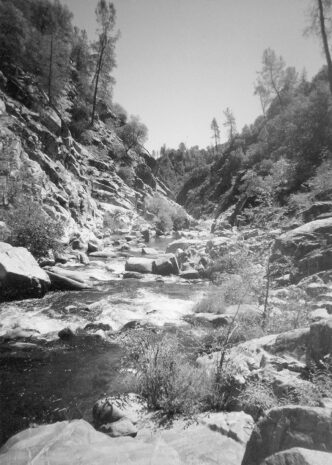

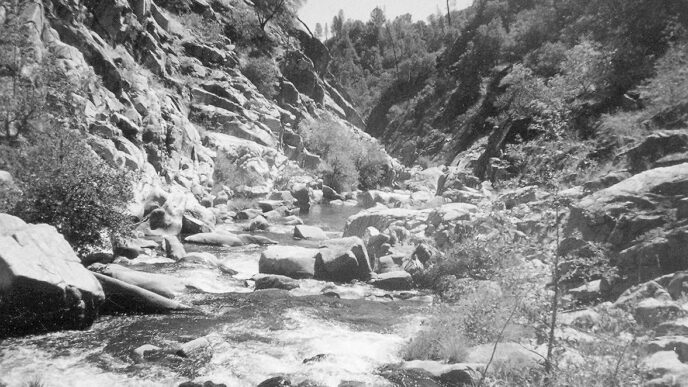

It’s early summer. The Sierra river I’m envisioning is a medium-sized one, well known for caddis hatches. I get there expecting a hatch, but there is nothing. (Do fish even really live here?) I’m tying on an E/C Caddis, and not just because it’s my husband’s pattern and I get them for free. It’s my go-to fly, even at times without a hatch. The trailing shuck of this fly and its above-water silhouette imitate bugs (caddisflies and mayflies) that tried unsuccessfully to hatch that morning or the night before and are now just drifting in the current.

More than half the time, I’ll also put on a Bird’s Nest as a dropper behind the E/C Caddis. (Cal Bird was the most amazing fly tyer, artist, and all-round cool guy. . . but I don’t get these for free.) The Bird’s Nest is so darn buggy-looking that fish can’t help but eat it. This combo is a killer in most caddis-laden Sierra rivers.

Ken Hanley, contributing editor, California Fly Fisher

My favorite bass pattern is the Dahlberg Diver. I especially enjoy using Whitlock’s frog version. Not only is it a terrific surface-oriented streamer, I have had solid success presenting the fly with a T-11 sinking head. The combination of sinking line and floating streamer is outstanding around steep, rocky shorelines or over deep grass beds.

Larry Kenney, contributing editor, California Fly Fisher

Fly choice has become more complicated than metaphysics lately as every fifth fly tyer tries to get his or her name on a pattern that’s slightly different from what was hot last year. I resist that complication to the extent that I can — which is to say I keep my own choices pretty simple, tie as few flies as possible, but am happy to mooch any new or oddball pattern that works for my friends. (Important note: always fish near friends who know more and are better tyers and anglers than you are.) When I can’t figure out what’s going on, or I can’t connect on a pattern that worked an hour or a day ago or on a big attractor dry like a Humpy or Royal Wulff that represents absolutely nothing but is fun to cast and watch drift, I brood over a box full of size 16 to 18 Pheasant Tail Nymphs, size 14 to 16 olive caddis pupae, Beadhead Hare’s Ears, and weighted marabou streamers. After one or all of those don’t work, I retreat to the plausible excuse that something is wrong with the moon or wind or sun or humidity and that the fish simply aren’t going to do what they should be doing. Of course, if something does work, it proves absolutely nothing.

Robert Ketley, contributing editor, California Fly Fisher

In the 1920s, Vogue compared Coco Chanel’s little black dress to the Ford Model T. In 1961, Holly Golightly wore a little black dress in Breakfast at Tiffany’s with devastating effect. In many ways, the little black nymph is the Model T and Holly Golightly of my lake fly box. Whenever a lake is devoid of insect activity and I am overcome with fly-selection paralysis (a common disorder in fly fishers), I reach for the Little Black Dress Nymph. Cast out on a long line, counted down a few feet, and inched slowly back to the bank or boat, the LBD nymph often produces fish. Any black nymph will do, though I am partial to flashbacks. “Little” for me is anything under 1/0. I typically use patterns in the size 12 to 16 range.

Stefan McLeod, angling writer

Anyone who has fished my home water, the Truckee River, knows that more often than not, there aren’t a lot of bugs hatching or fish rising. When the insects aren’t active, I always fish a large stonefly nymph, size 6 to 12, because trout will rarely pass up such a high-calorie meal, even in the absence of a hatch. These large bugs are found in almost every trout stream or river, and since they can live as nymphs for up to three years, a stonefly nymph can make your time on the water a little more productive when the bugs are few and far between.

Two of my favorite stonefly nymphs are Mercer’s Poxyback Golden Stone and a stonefly pattern I developed for the Truckee River called the Brick. When fishing a stonefly pattern, I usually go with one of these nymphs fished under an indicator with a few split shot attached to the leader, but from time to time, I search for willing trout on the surface with a Stimulator dry fly that imitates an adult stonefly.

Seth Norman, associate editor, California Fly Fisher

On trout streams, I make it rule to find out what’s living below before I tie anything on. This is how I taught myself to fly fish. Failing to sample — in my case, failing to seine — makes me feel like I’m fishing blind. I may work my way through several species of bugs, crustaceans, and baitfish. If none pan out. . . .

If it’s summer, I might figure there’s an important terrestrial at play. Jim Sherer taught me that an ant is a good option; I’m still fishing a batch of enamel-covered balsa tidbits made by B-17, which I think work better for their itty bitty legs. If I have to go deep, and I often do, I pick a searching nymph or flymph designed by one of three Daves: Hickson, Hughes, or Whitlock. To this, I add a small dropper — either a black puff of marabou tied on a size 18 hook or a Brassie that size or smaller. I make sure this pair gets down, way down. Nothing then?

Hey, if this is likely to be a one-fish day, let’s make it memorable. It’s bigstreamer time, possibly a wool-headed sculpin, but more likely a pattern representing the fry of the fish I’m after, as close as I can guess to the right size for the season. Pound the banks, rip across deep holes, drift into tailouts as the light falls, growl lines from Winston Churchill: “Never give up. Never surrender.”

Chip O’Brien, contributing editor, California Fly Fisher

I dubbed this fly (sorry) the O’Brien Bird’s Nest, but it’s my adaptation of another version of the Bird’s Nest once tied by guide and friend Tom Peppas. As far as I know, no one else is using this particular dubbing combination anymore, and it has always worked very well for me. The body is made from one package of Hareline chocolate brown dubbing and one patch of natural Australian opossum hair, mixed. I added a tungsten bead and teal feather fibers for the wing and tail.

My favorite way to fish it in rivers is short-lining off the end of my fly rod. When I need to get it out farther, I add a small strike indicator.

I think this fly works so well because it looks like a lot of different bugs and moves well in the water. In lakes, I hang it 4 to 6 feet under an indicator, and it makes an effective Callibaetis nymph. I tie it in sizes 12 and 16 to cover a wide variety of insects.

John Parmenter, angling writer

As a trout fisherman, most of the small streams I fish are here in Southern California. I’ve learned that on these streams it’s not so much about matching the hatch as it is about tying on a dry fly that has proven it will bring fish to the surface consistently. Hands down, the top two flies for me are the Parachute Adams Emerger and the Wright’s Royal. For smaller, quieter water I usually rely on the Adams emerger to get the job done. Its buggy coloration, low profile on the water, and high visibility make it a proven winner. But when the water’s higher and faster, more often than not I’ll go with the Wright’s Royal. Its hair wing helps it to ride the riffles well, and I believe its attractor-style body gives it an edge over a caddis. Now having said all that, I don’t expect my choices to match those of others necessarily, and they shouldn’t. If you can’t fish a fly with confidence, it’s best left in the box.

Trent Robert Pridemore, angling writer

When careful observation shows nothing happening on the surface, I turn to generic flies that can represent a number of fish foods: Offer your prey a sensible, opportunistic meal. These have worked for me over and over in the past.

Denny Rickard’s Stillwater Nymph in medium olive, size 12 or 14, is my starting point on still waters. This fly can represent a nymph, a scud, a leech, or even a minnow. Although it’s a generic pattern, it is also a very good imitation of a Callibaetis nymph. That’s our major stillwater mayfly and is available through much of the season. I look for a weed forest or the edge of weed clusters, where I can make a slow retrieve. Though it has been popularized as a trout fly, I’ve used the Stillwater Nymph successfully on bass, bluegills, and perch. I tie it as small as size 16 and as large as size 10. The standard material for the legs is a brown hackle fiber, but Jay Fair’s “fiery orange” saddles can get fish excited as they key on orange underbelly scud egg clusters. I use this pattern as a point fly or as a trailer behind a larger Woolly Bugger. The basic starting retrieve is two short, slow pulls, followed by a pause and a longer strip. When that isn’t working, I try a slower retrieve. If nothing happens in 15 minutes, I change something, but not the fly — depth, size, retrieve, or location.

André Puyans’s A.P. Black was the cornerstone of his famous A.P nymph series. It is my switch hitter. It can be tied as small as size 18 or 20 for a midge imitation, size 14 and 16 for mayfly nymph imitations, and as large as you want to imitate a big, dark stonefly nymph. I carry a whole row in one of my fly boxes. It can be fished on slow-moving spring creeks or tailwaters, in the pools, runs, and riffles of a freestone stream, or as a stillwater pattern in lakes and ponds.

Andy preached proper proportions in fly tying, but his masterpiece can be customized. The original black beaver or newer synthetic body dubbing can be picked out to make an ugly, enticing bug. The fly can stripped slowly in the film or weighted with lead wraps and fished deep. In moving water, look for the soft edges.

In lakes, seek out the food factories that are found around springs, in weed beds, near rock outcroppings, at inlet streams, and around shoals. Like the Stillwater Nymph, use the A.P. Black as a point or as a trailer. It will catch almost any freshwater species. A buggy size 8 took a winning largemouth in a fly-rod tournament.

Peter Pumphrey, angling writer

I am not sure that I have a “go-to fly.” Until you deliberately think about what you do, it is easy to overlook the degree to which your preferences shape the way in which you fish.

I am a dry-fly guy and will often insist on fishing dries even when it is patently useless. This bias costs me dearly when fishing Hot Creek or the Owens River, but it is a conscious choice, and I must be willing to absorb the consequences in terms of fewer fish. I also favor fishing in out-of-the-way places removed from the roads and the crowds. These streams (no still waters for me) are smaller and are subject to wide seasonal variations in size and water clarity. They are less biologically rich and therefore present fewer hatch dilemmas. In writing this, I see how each of these biases reinforces the other. Sometimes the question is where the fish are in the stream, rather than which insect at which stage is hatching, so I need a pattern that locates the fish. A major in-fluence on my final choice is the fact that I am not getting any younger, so visibility counts for quite a bit. In the early season, I will probably tie on a parachute pattern, maybe a Hare’s Ear, Blue-Winged Olive, or, if I am truly exploring, a Royal Parachute or Royal Wulff. As the day warms up, I shift to Cutter’s Perfect Ant, which rides high on these often choppy waters and is surprisingly easy to see. Because it’s a terrestrial, responses to the ant pattern seem to be to be less dependent on the invertebrate activity in the creek. Also, fish seem to react to it with enthusiasm.

Having said all this, I am afraid that I often pick a starting fly while imagining my day during the hike in. I can see the weaknesses in this form of fantasy fishing, but some days just feel like a Stimulator.

Scott Sadil, writer and educator

So many variables. But let’s just say we’re looking at a classic trout run. I start at the bottom. If it’s slick and slow . . . a size 16 Parachute Adams. Some pace and bounce to it . . . why not a small Green Humpy? I fish up, first cast tight to the near bank, then fan out to the middle, until I can reach the top of the run, which is where I try to make my very best casts, right into the sweet spot.

If nothing happens, I tie on a little soft hackle — Partridge and Green in faster, bigger water, Hen and Green or Hen and Grey if it’s slick and slow. I start at the top, all the way up in the riffle, and swing into the soft water. I work my way down through the run.

At this point, if I haven’t seen or learned anything about this spot, haven’t seen a fish rise or a bug fly by, I walk up to the top again, clip and retie my tippet, leaving tag ends on the blood knot. I tie on two flies. Today it will be a Wild Hare on the point, a Wyoming Mayfly Nymph or Pale Morning Dun Nymph above, a pinch of split shot in between. Standing just inside the top of the run, I cast short, almost directly upstream, lift tight to the flies, and lead them (without pulling or tugging), rod tip raised, downstream.

In the past three decades, there have been many different names applied to this same basic technique. My name — Sadil — which nobody seems to be able to pronounce on the first try — is Bohemian. Bohemia is part of Czechoslovakia. But I don’t think they named this technique because of me.

John Sherman, photographer and manufacturer’s representative

My go-to fly when fishing the Delta for bass is Charlie Bisharat’s Muskrat, 4/0.

It’s my primary searching pattern when seeking giant largemouths on the surface. The Muskrat walks back and forth like a Zara Spook and can be pulled under the water like a Dahlberg Diver. It eliminates most of the small fish and high-grades primarily good quality fish. There are other flies that might elicit more strikes, but this one is deadly for giant bass.

When fishing the Delta for stripers, my go-to fly is Dan Blanton’s Flashtail Clouser. This is the fly that I have on when striper fishing 70 percent of the time. I vary the colors of the fly based on water clarity and the baitfish in a given area. As a general rule, I like chartreuse over white or black over chartreuse in stained to dirty water and more natural colors, olive over white or gray over white for clearer water. I observe the size of the bait and match my fly size accordingly. I tie these flies to be indestructible with yak hair for the wing and flash and Slinky for the primary material, not bucktail, which doesn’t stand up to the abuse of dozens of stripers. For me, tying flies is like homework, and I when I do spend the time to do it, I want the fly to last.

Bill Sunderland, angling writer

With the emphasis on stillwater fishing, I have a couple of goodies I almost always start with — a burnt orange Jay Fair Special (his new version with a longer marabou tail) and a Carey Special as a dropper. The weighted Jay Fair Special, in about a size 10 or 12, not only gets you down in the water, but also tends to get a fish’s attention with its undulating tail. The Carey (size 12 or 14) is a wet fly that can be fished either in the surface film or anyplace underneath the surface. I tie Careys with a peacock herl body and a soft partridge collar that extends back to (or even beyond) the bend in the hook. This, too, undulates with your strip.

Although they don’t really imitate any bug, they both give the impression of being alive, which is a key to enticing trout. And remember: Strip slowly interspersed with pauses.