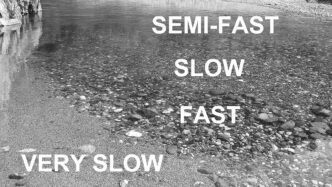

The name of the creek is irrelevant. What’s important is that it rises from springs high up a mountain slope, and although it flows beside cabins and across two golf courses, much of the watercourse descends through forest before it hits bottom on the flatlands of a city’s downtown. There, a long culvert pipes the stream beneath an interstate freeway, and a second culvert forces it to take a hard left into a concrete channel, which then carries it under the main business thoroughfare. When the creek reappears, it remains in a man-made channel, although this one is formed with earthen banks between a major arterial and a railroad. The landscape here is one of industry, and also of apathy and neglect: loaders, trucks, and other machinery sit helter-skelter on the otherwise vacant, debris-strewn site of a long-gone mill; graffiti-covered cargo containers abut the railroad tracks; trash, blown in from roads and the commercial area to the west, flutters in the breeze. And the earth literally trembles when one of the frequent trains passes by.

It’s an odd place, an ugly place, to consider throwing a fly, particularly given the blue-ribbon trout river that in fact flows a short walk away. But the creek’s wilder sections upstream hold small, jewel-bright rainbows and brookies, and even in this industrial zone, mere feet from the railroad tracks, the stream’s corridor is here and there thick with grasses, willows, and aspen, and hardy conifers have managed to flourish on levees and benches just above the flood plain. Although easy to miss, given the overarching feel of desolation and abandonment, these unexpected displays of vitality cause one to wonder, can fish thrive, as well?

Leaving my fly rod at home, I begin my inquiry with a hike along the creek shortly after noon on a sunny, early-summer day, hoping my looming presence will frighten fish into movement and, just as critically, that I’ll see them as they skedaddle for cover. The channel is narrow enough that I can cross it in places with a bit of a jump. But reaching open water along the lower stretch proves surprisingly difficult — the willows are nearly impenetrable, providing few spots where I can view the stream, much less cast a fly onto it. Several branches slap at my face as I maneuver through a thicket, leaving a dark smudge on my eyeglasses. The smudge moves. It’s a Callibaetis mayfly, a spinner, ready to begin its mating flight when evening arrives.

Farther on, the willows begin to thin, and signs of beaver activity appear. The obstructions created by the beavers — most barely resemble dams — have collected surprising amounts of silt, an indication perhaps of problems upstream. I come across discarded tires, water-carved foam insulation, plastics, rusting metal, and a small wooden picture frame bleached silver-gray by the sun. Old fence posts tilt out of plumb in the bitterbrush along the railroad. I skirt boulders that look as if they were pushed beside the stream when the land here was graded long ago.

The fish remain hidden until I reach the deepest and widest beaver pond on the stream, situated at the downstream end of a culvert. It’s an unlovely spot, set between storage yards, but the rings of a trout’s rise are spreading across the pond’s surface, and as I move closer, with caution this time, I glimpse the white-tipped fins of a brookie, perhaps eight inches long, as it unhurriedly sinks back into the depths. Aha. I watch for a while longer, but the fish refuses to reappear for a more thorough examination.

Upstream of the culvert, a layer of sediment has spread across the creek bed, which appears too shallow for the comfort of fish. Within a few strides, however, willows again crowd the bank, interspersed with pines, and the channel deepens. It looks like good habitat, but as before, if the trout are here, they’re invisible. The beavers, however, have obviously found conditions attractive. I keep moving, ending my inspection at a section recently scooped out and engineered for flood control by the local municipality. The size of the disturbed area and its unfinished revegetation mark this as water where I’m unlikely to find trout of catchable size. There’s no reason to go farther. I turn away from the stream and cross the flat wasteland of the mill site back to the railroad tracks and my vehicle.

The sharp odor of creosote rises from the railroad ties.

I return in the evening, with perhaps an hour of light remaining before nightfall. I’m wearing a heavy shirt, a dark ball cap, and jeans tucked into rubber boots — tough clothing that won’t rip on barbed wire or beaver-gnawed branches. One shirt pocket holds a small fly box containing a mix of attractor and imitative patterns, another holds a single spool of tippet monofilament. That’s it; no waders or over-stuffed vest. This is fly fishing at its simplest. Although I often use short fiberglass rods for creeks, the need to cast tight loops into small openings on this stream means I’m fishing a faster graphite rod with a weight-forward line.

I park at the far end of the creek, near its confluence with a larger river. This is a spot where transients sometimes camp — it gets little traffic, offers a good supply of clean water, and the willows obscure visibility. Tonight, though, I’m alone. A few yards away, the creek leaves a culvert beneath the railroad embankment and immediately drops into a brush-enshrouded pool about ten feet in diameter. The water’s surface mirrors the pearlescence of the sky — I can’t determine the depth. But the place looks fishy in a good way, and, crouching, I lay a small imitation of an ant near the center of the pool. The fly floats for one second, two, then vanishes in a snappy rise. Fish on! It makes several leaps before coming to hand — a well-proportioned, five-inch rainbow.

I climb up the railroad embankment and stand on the tracks. Below me, on the other side, the creek flows through an open, grass-lined slot, the surface of which is marred by the wake of a trout that saw me first. It’s a reminder that stealth is critical on creeks. I begin to fish my way upstream, trying to pop casts between branches and too often ending up snagged. If there are fish nearby, I put them down when I retrieve the errant flies. Other flies I can’t retrieve and have to sacrifice: that first ant, a Parachute Adams, one of Ralph Cutter’s E/C Caddises. Still, another small rainbow comes to hand, and I miss a strike.

The sky has turned to cobalt as I approach the beaver pond where I had spotted that large brook trout earlier in the day. I see the reflection of the moon on the water’s surface, and it’s suddenly multiplied by the ripples of a feeding fish. I’m quickly on my knees, trying to hide both from the trout and from the cars that pass just yards away, some of which are no doubt driven by anglers.

I gather several loops of line and cast the fly toward the back of the pool. It settles gently to the surface, and within an instant a trout takes it, but in another instant is off. I cast several feet farther up. Another take! Nope, a miss. I cast again, and a fish again won’t stay buttoned to the hook — but hey, three casts and three hits: it’s a streak I like. On the fourth cast, the trout remains attached, and I land a brookie.

By this time, every fish in the pond knows what’s going on. Subsequent casts draw no attention, and I finally tangle the tippet and fly on a pile of sticks, where they remain after I try to tug them free.

It’s now too dark to rerig, but I’m grinning, satisfied with the outing. Although this creek is hardly brimming with fish, or, more accurately, with fish I’m able to tempt to a fly, it displays a hardscrabble vigor that belies its location in a blighted industrial area. It is a survivor. I get the feeling that perhaps, however much we disfigure the land, the urge to life that drives nature will slowly, surely, seek to undo the damage and find a balance. In the moonlight, the trucks and structures nearby have softened in shape, looking almost as if they’re sinking into the soil, eroding with the wind. I begin my walk back to where I’ve parked. Behind me, to the west, the dark bulk of the Sierra looms over the small, scattered lights of a downtown that grows more distant with every step.