Every summer, schools of calamari invade the shallow edges of Monterey Bay. These finned mollusks have one goal in mind — reproduction. Millions, if not billions of squid invade the shallows and create a “megahatch.” They are greedily dined upon by an assortment of fish, birds, and mammals. White seabass and halibut, both of which are superb on a dinner plate, are especially fond of calamari. Given the chance to land large and very tasty fish, the local sport fleet seldom takes long to respond to reports of spawning squid.

This year, the report went out in late June. A school of squid had stationed itself off the kelp beds by Capitola. Local fishing Web sites and newspapers displayed pictures of anglers with white seabass ranging from 20-pound runts to 60-pound, drag-frying monsters. There was also a decent showing of doormat-size halibut, too. With the chance to hook up to a heavy bass or a seriously fat flattie, even diehard salmon fishers managed to tear themselves away from a solid king salmon bite. I found I had to scratch a serious itch, as well.

In early July, Steve Rigg and I arrived at the Capitola wharf around 6:30 A.M. Sleepily, we clambered into a bright-orange rental boat and had a brief argument with the motor, which was clearly unhappy about being pressed into service. Eventually, the motor got over its aversion to cold, damp mornings, and we headed out onto the bay. Straining to see through a dense gray fog, we picked a zigzag path around moored sailboats and patches of kelp. Fortunately, it did not take too long for us to find the squid. A swirling mass of birds barely one mile from shore was a dead giveaway. Pelicans made short, lumbering flights, gaining just enough altitude to make less than graceful dives. Incessant squawking from dozens of terns provided sharp relief to the white noise created by hundreds of constantly bickering gulls. It was clear that the squid were not running deep.

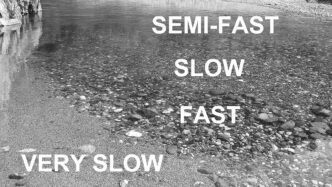

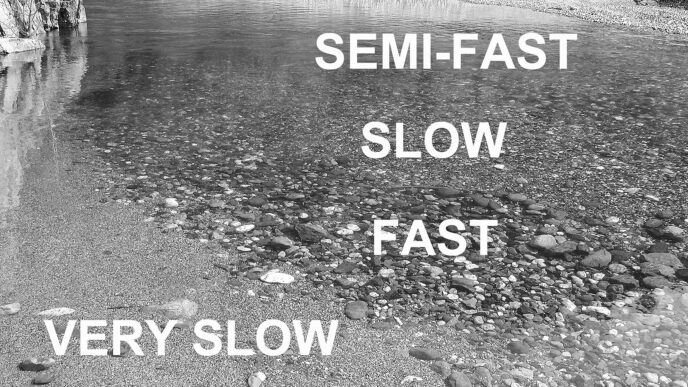

Accompanying the birds were dozens of bottlenose dolphins and innumerable sea lions. It was quite a carnival. A fleet of boats had also gathered in the area. As we arrived on scene, it quickly became apparent just how large the squid school was. The depth finder showed two distinct bands, one about 10 feet down and another that followed the bottom contours just 50 feet down. We traveled for hundreds of yards, looking for the edge of the school. Eventually, the sonar showed some thinning of the upper band. This was where we figured the bass would be working and where our flies might stand a chance of being seen.

Steve and I did some quick math and estimated we were sitting on top of 50 acres of calamari. The total tonnage of high-quality marine protein beneath us was mindboggling. Not surprisingly, enthusiasm in the boat was close to fever pitch. We shut down the cranky outboard and made preparations to catch massive fish.

We had 10-weight rods armed with quick-sinking T-14 tungsten-weighted shooting heads and squid flies. My flies were crude mash-ups of white hackle, Flashabou, and fabric paint. When it comes to fly tying, I have a serious aversion to anything fussy. Steve had put far more effort into his much more realistic patterns. I swear, the eyes on some them followed my every move.

Instead of anchoring, we allowed the boat to drift slowly with the current. We figured this was the best way to cover the water and find feeding fish. We sent outcasts to the side of the boat and let the lines sink through the water column. We discussed fish recipes and debated the point of stupid sports such as golf and cricket. After each cast, we counted the fly’s descent in seconds. When one of us hooked up, the magic number could be easily replicated. We figured we would be home by midday with dinner for 50 or more. A hero’s welcome was all but assured.

After an hour or so, we realized there was a problem. Our flies were, for all intents and purposes, crude hopper patterns in the middle of a biblical locust plague. There was too much easy-to-catch molluscan protein finning around the bay. Our flies simply didn’t stand a chance. Even the guys fishing live squid were blanking. Clearly, the odds of us hooking up to an athletic seabass or fat flattie were pretty slim.

We decided to break for a 9:00 A.M. lunch and consider our options. After careful deliberation and some much-needed carbohydrates, we agreed that it was time for a change of tactics — and quarry. We set aside the heavy rods and T-14 lines. Out came lighter munitions: 6-weight rods armed with high-density shooting heads and size 6 flies. If you can’t hook ’em, join ’em.

It did not take long for us to hit pay dirt. The approach was fairly simple. Cast out 30 or 40 feet, allow the line to settle down about 10 feet, and then retrieve the fly rapidly toward the surface. The bites were rattling/tapping affairs that made the line skip in your fingers. Takes were generally midway through the retrieve, but often, we would see gangs of squid following our flies all the way to the surface.

As one might imagine, from an animal barely eight inches long, the fight was not exactly epic. It was, however, highly entertaining. Following the tapping take, the squid would attempt to jet away, making the tip of the rod dip down in a series of fast pulses. At the surface, the squid would send arcs of seawater into the air and on several occasions into the boat. Every so often the jetted seawater would be mixed with ink, making an interesting pattern on faded jeans and expensive flyfishing shirts. As the squid were skidded across the top of the water and brought into the boat, their bodies went through a fascinating series of color and pattern changes. Who needs National Geographic when you can have the real deal?

After we had caught a dozen, I figured it was time to do some experimenting. Did the squid have a color preference? I selected three flies for this important scientific research: a white bonefish fly, a gold-bodied surfperch fly, and a flaming-red Ally’s Shrimp. Red was the hands-down winner, accounting for 80 percent of the hookups. I noticed that we had hooked only males and wondered if the females were the bottom-hugging band on the depth sounder. I grabbed the T-14-rigged rod and tied on a size 6 bright-red General Practitioner, a pattern that should be in every serious calamari fly fisher’s box. The Atlantic salmon fly descended into the cold, gray depths of the Pacific. Following a slow count of 60 to make sure the fly was close to the bottom, I began a surging retrieve. Nothing happened until the fly was about 15 feet down, when it was back in among the lit-up males. The whereabouts of the females remained an unsolved mystery that will have to be the subject of further intensive research.

The wind came up around 11:00 A.M., driving a stampede of choppy waves across the bay. Things quickly became wet and uncomfortable in the small wooden boat. Following some serious double hauls on the outboard’s pull-start cord, we headed back to the wharf. We had left in search of giant seabass and fat halibut. We returned with a gunnysack of calamari. We could not have been happier, and dinner that night was superb.

Squid: It’s What’s for Dinner!

Squid is “high-quality marine protein” indeed, and it’s both easy to clean and easy to cook.

It’s easy to clean, because there aren’t a whole lot of parts to a squid, and they come apart with no trouble. Grasp the body in one hand and the head in the other, twist, pull, and separate. With the head will come out the snotlike innards. (Sorry, but innards are always a little icky, and that’s what they look like.) Separate and reserve the tentacles by cutting them off, leaving the eyes attached to the innards. Pop out the beak from the middle of the tentacles and discard. Reserve the tentacles; they’re yummy.

If you see a black vein in the innards, that’s the ink sac. The ink can be used in cooking in a variety of ways, as both flavor and color. If your recipe calls for squid ink and your squid has some, carefully remove the sac, puncture it, and milk it into a little water, wine, or stock. A little goes a long way, and don’t get it on anything you don’t want inked.

That leaves the body. Inside, there’s what looks like a piece of plastic — the “cuttlebone” that gives the cuttlefish both a name and a spine. Pull it out and discard, then rinse the body inside and out under cold water. Most cooks remove the skin — just peel it off with your fingers — although it is edible. It’s just that the rings of squid aren’t as pretty with the skin on. Some also pull off the “fins” at the back of the body, if the squid are small, but the fins, too, are high-quality marine protein. Cut the body into rings — say, half an inch wide — add them to the tentacles, and you’re ready to cook.

Squid is easy to cook because you should either cook it only very briefly or let it simmer for a looooong time. Anything in between, and you might as well be cooking with rubber bands, because any other application of heat causes squid to become incredibly tough. So on the one hand, it’s great for stir fries at high heat and can replace shrimp, for example, in any Chinese recipe that calls for them. Just add the squid last and finish the dish quickly, as soon as the flesh becomes opaque, no longer pale and sort of translucent.

Squid is also great for long, slow stovetop braises, since braising breaks down the proteins, just as it does in tough protein from land-based critters. One classic braise is a French dish, squid and leeks in red wine.

Squid and Leeks in Red Wine

The white and pale-green parts of 2 pounds of leeks, cut in 2-inch lengths

Olive oil

2 pounds of cleaned squid

2 tablespoons flour

A pinch of cayenne

Salt

1 teaspoon mixed dried herbs, such as thyme, oregano, and summer savory

1 bay leaf

8 cloves of garlic, sliced thin

2 cups good red wine

1 cup water (or wine and water, 2:1, to cover)

Chopped parsley

Fried-bread croutons

Gently cook the leeks with a few pinches of salt for 10 minutes, carefully turning them occasionally, then remove and set aside. Sauté the squid in the same oil over a higher flame until the liquid that comes out has mostly evaporated, sprinkle over the flour, cook of a minute, and add the cayenne, herbs, garlic, and a bit of salt. Finally, while stirring, add the wine and water. Bring to a boil, return the leek sections to the pan, and cook, covered, at a low simmer for an hour and a half or so, until both the leeks and the squid are completely tender and a sauce has formed. When serving, scatter the dish with chopped parsley and croutons. Serves four.

Bud Bynack