When this year’s March storms cleared, and I was able to see the Sierra Crest from my front yard, I was struck by how beautiful the sweep of peaks are when they are covered with fresh snow. I had spent the week of bad weather fussing with gear, looking at maps and wish lists, and rereading favorite fishing stories. In other words, I had contracted full-bore spring fishing fever. However, one look at the mantle of new snow brought the dread of runoff and memories of making a trip to a favorite stretch of river and hurrying from the car, only to find high water had made the spot of my dreams unrecognizable and truly uninviting.

Runoff from snowmelt is a fact of life every trout season. Usually, it is just a nuisance. However, this year has brought snowpack with water content in the 150 percent range throughout the Sierra. A look at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power snowpack and water content measurements tells us that runoff will be a fact of life deep into this summer.

There are several ways to cope with the effects of snowmelt. One is to look at the factors that affect the timing, magnitude, and duration of runoff, gather as much information on these factors as you can, and then try to plan accordingly. Another is to develop alternative strategies that allow you to fish places other than those that have raging waters.

Runoff Factors and Information

The timing and magnitude of snowpack runoff depend on many factors. Some of these affect the entire region, and others are more limited geographically. All are interrelated. The art of runoff prediction involves juggling all of these factors and is

certainly beyond the purpose of this discussion. However, anglers should consider the following variables in deciding when and where to fish during the runoff period.

Snowpack. This is the most obvious consideration and refers to the amount of snow accumulated during the winter. The snowpack is measured in terms of the depth of the pack and its water content. It is important to make certain which of these is reflected by any data source used in planning a trip. Water content is the more relevant factor in terms of runoff levels. Snowpack levels, however, can be used to track trends and can be found at the resource sites listed in the sidebar.

Ground Condition. Not all snowmelt goes directly into streams. Its first destination is the ground that underlies the snowpack itself. The capacity of that soil to absorb and retain water from melting snow directly affects stream levels. In low-precipitation years, the ground is less saturated, so water will flow into the soil rather than into a stream. Examine historical snowpack data from the last couple of years to get a feel for saturation levels. This information will also provide a general perspective for the Sierra as a whole. Also, a drainage with a high percentage of rocky, solid ground will contribute a higher level of water to its streams.

Slope Elevation and Aspect. Again, this is somewhat obvious. Higher-elevation areas will contain a deeper snowpack and retain it longer than those below. For that reason, streams at high altitude will tend to run clearer longer into the season than those at lower elevations, which pick up runoff sooner and then reflect the cumulative effects of water as it begins to come down from above. North-facing drainages will melt later and run off at a slower rate than those with a south-facing aspect. Thus, you may want to visit the north slopes early in the season and wait for the south faces to clear from their more intense snowmelt.

Temperature. Both day and night temperatures are important. In the spring, air temperatures return to subfreezing levels and halt snowmelt overnight. Runoff from this pattern is significantly lower than is the case when the temperature is above freezing 24 hours a day. Look at the readings for different altitudes. As soon as the night temperatures rise at a given altitude, the runoff effects at that level and below will begin to increase. Lows in the forties will have a dramatic effect on runoff.

However, daytime temperatures drive snowmelt. As the spring turns into summer, the sun rises higher in the sky, and its rays strike the snow surface for more hours during the day. There are times when this increase in solar heating moves at a gradual pace, but every year brings heat spikes in which the high temperature suddenly increases for several days. These hot spells bring dramatic reductions in the snowpack and produce much heavier runoff and more water discoloration. Be prepared for challenging conditions during or immediately after such an event.

Drainage Area. Again, this is straightforward: as the size of a drainage increases, the amount of runoff that flows into a stream must also increase. Look for smaller, tributary drainages, especially those at higher altitude with a northerly aspect.

North/South. Runoff starts earlier the farther south you are in the Sierra. In the eastern Sierra, peak runoff in Inyo County is usually in late May, while the same level is not reached in Mono County streams until three or four weeks later.

Watershed Management. Nearly every Sierra stream contains impoundment facilities. These dams act to retard the downstream runoff as they capture snowmelt. Their effect on stream levels is dependent upon the ways in which they are managed. Some reservoirs are drawn down in winter, either for maintenance or to make way for expected snowmelt. Their capacity in the early spring is a crucial factor and can be determined by looking at the information sites listed in the sidebar. Many of these impoundments do not have a capacity equal to peak flows in wet years. Once the dam overflows, the downstream effects are significant and could last for some time. Check the sources of dam operation information throughout the year, because different management schemes call for high water releases at various times, which can result in unexpectedly high flows in late summer or fall.

Strategies for Coping with Runoff

Peak runoff fills streams with large volumes of fast, cold water. These conditions are hard on trout and cause them to behave differently from the ways they act later in the season. Although these behaviors are normal and seasonal for the fish, they strike anglers as unusual, because our thoughts are primarily focused on prime conditions. I mean, who sits around and daydreams about fishing their favorite creek when it’s blown out? Faced with the prospect of a protracted period of high water, one can either curse the gods for monkeywrenching yet another fantasy of perfect fishing or try to figure out what can be done in the face of unwanted conditions.

Of course, you can always change your dates. If you plan one or two major trips a year, push them back on the calendar. This is a good year to take in some of the magic of fall fishing.

If you must fish during runoff, there are actually a fair number of options for you to consider. I have tried the tactic of sitting it out and waiting for the waters to fall, no matter how long that takes, and believe me, it doesn’t work. My resolve cannot stand up to warm early summer days. So, for starters, pick the best time to fish. Go out early in the day to take advantage of the fact that runoff decreases overnight. On any day, no matter what the conditions, there is a window of time during which flows will have moderated. This may be an example of tortured optimism, but go with it. Also, as bad as the water conditions may be in the first part of the season, they will get worse when the peak runoff arrives. Get you fix in May, before the truly high flows appear in June. Look at the historical flow charts for years with similar snowpacks, and you can find a way to sneak into water levels that may not reappear for weeks after peak runoff.

Smaller tributaries will clear and return to “normal” earlier than larger streams. This might be a good time to explore some of those little brooks or creeks that you pass by on the way to you traditional favorites. Take a look on a map for tributaries that flow from smaller drainages, especially those situated with a northern aspect. Remember that the headwater areas of streams will enter high runoff later and clear out more quickly than the waters at a lower elevation.

If you simply have to fish that favorite larger river, learn to see it with new eyes. Trout move from their “normal” locations, because they are stressed by high-velocity, low-temperature spring flows. Look for them in places you would consider highly unusual later in the year. Trout seek out soft water, where they can hold without expending unsustainable amounts of energy. Seek obstructions to stream flows, such as downed trees, large rocks, and log and debris jams. Fish will move to the slower water behind these structural features.

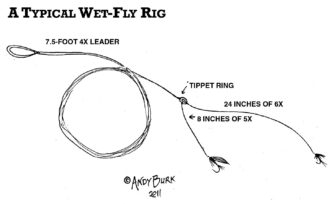

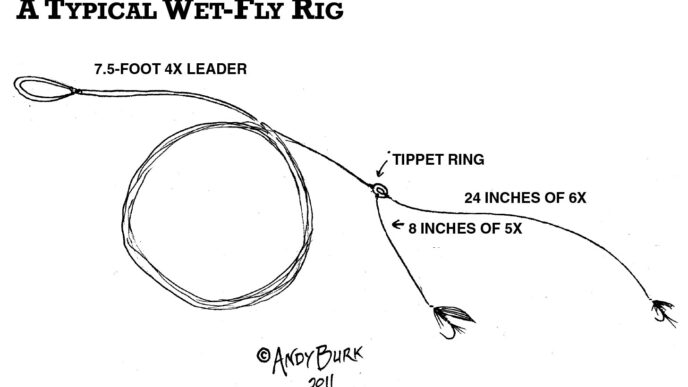

By and large, spring runoff means fishing subsurface flies. Trout are not as oriented to the surface, and higher flows move lots of subsurface food. Try fishing a nymph or a two-nymph dropper system through the seams along the soft-water spots described above. Water at the stream bottom moves more slowly than at midlevel, so when fishing deep, fish slowly. The old adage that if you are not hanging up, your fly is not deep enough is true. High current speeds require more weight to get your fly down to the fish.

Another effective technique is to hang a streamer in these current seams. Let the fly stay stationary for as long as you can stand it, then bring it back in a serious of slow retrieves. Cold water means that both predator and prey will be more sluggish than you might expect.

Even if you are a dry-fly person, all is not lost. Fish the edges and shallow areas that you would ignore in August. Fish move into these areas because the current is often weaker there, and these areas are likelier to experience rising water temperatures during the day, improving the comfort level for trout. Rising temperatures also influence the emergence of insects. Try the submerged gravel bar where you will be standing on dry land in two months. In the spring, trout often hold and feed in water barely deeper than their dorsal fins. Try the inside, shallow water in sweeping curves, as well as areas of flooded vegetation, such as willows. Finally, do not ignore the side channels, which may be dry later in the year, but provide a fish haven in times of high water.

Check your maps for areas, such as meadows and other wide, low-gradient stretches, where a stream’s velocity might drop. Look also for ponds or small impediments in the stream flow. Beaver dams are another target. Remember that the tailwaters of dams and lakes will provide a reduced flow of clearer water with a more consistent range of temperatures.

Take some time to think about spots that will be less affected by the snowmelt, too. If you are a stream devotee, consider visiting some still waters during the first half of the season. Lakes and ponds are far less influenced by runoff and can often be invigorated by a rise in water level. Just remember that the fish will be more spread out in a runoff-filled lake or reservoir, and the water will be colder and deeper than later in the year. High-altitude lakes will take longer to reach ice-out and to become accessible, but lower-altitude waters will usually be available for angling from the beginning of the season.

Be Careful Out There

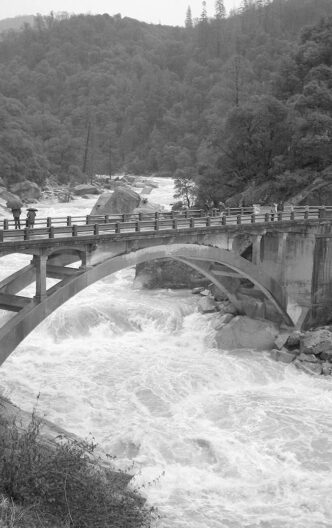

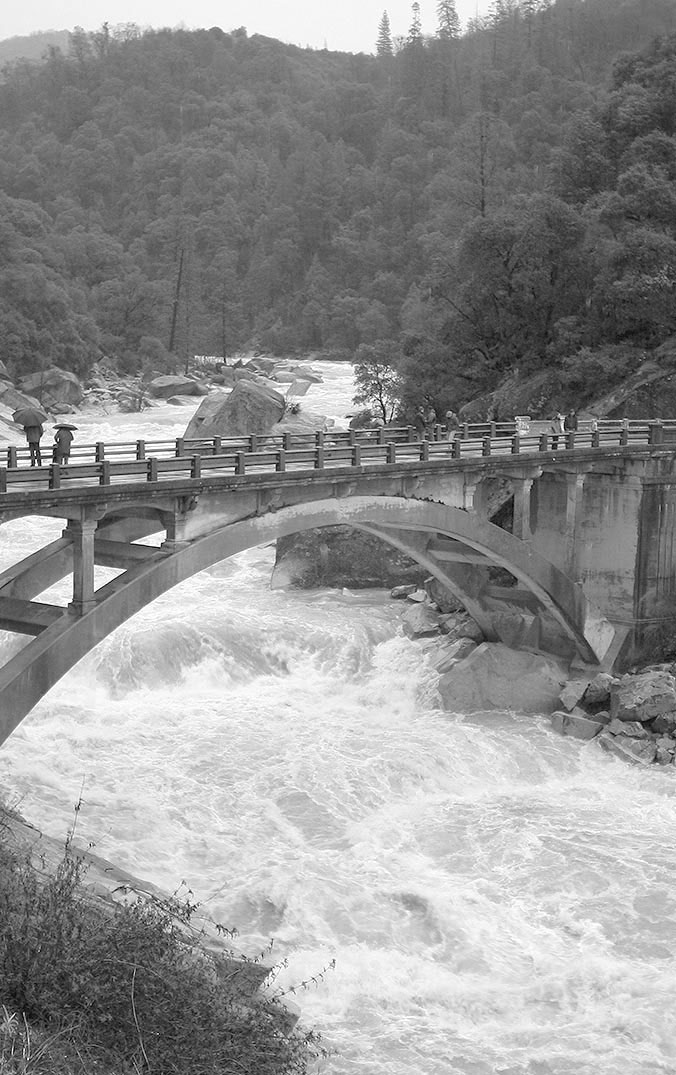

High water poses some safety considerations for the angler. Peak runoff is treacherous. If you are accustomed to wading your favorite river in late June or July, you cannot assume you can do so in a big snow year. The strength of the current is easy to underestimate, even in parts of the streambed that are normally easily waded or even dry. Water will be flowing in unusual places, and these can be unstable or tangled with roots and vegetation. The temperature of the water is also very low, and it does not take much exposure to court hypothermia. A river such as the Middle Fork of the San Joaquin is simply dangerously unwadeable early in the trout season of a year like this one.

The same cautions apply to stream crossings if you hike or backpack to a fishing destination. During high water, fords are often unstable or entirely gone. Flows are cold and fast, and it does not take a lot of depth to take you off your feet. Know the techniques of safe crossing, time your trip to make problematic crossings before the creek reaches its peak for the day, and don’t take foolish chances.

Silver Linings

The situation is not all negative. As you stand next to a raging June river, keep in mind that there are silver linings associated with all this. Streams, even big rivers, need high-water events to maintain their health. Of course, this does not include an event such as the 1997 West Walker River disaster, when the river, swollen by rain, runoff, and mudslides, devastated the canyon, but it does include years with runoffs at 150 percent or more of normal. Riparian vegetation depends on pulse flows that carry seeds and nutrients and that provide moist soil that enables recruitment of new plants. High-water years also raise groundwater levels, which sustain riparian areas. Healthy streamside vegetation provides shade for trout during the height of summer, anchors banks (preventing erosive damage), and provides habitat and nutrients for both aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates.

Runoff flows also remove silt deposits that cover and clog spawning gravels. The creation of silt beds negatively affects vegetation and trout and insect populations. The high-water periods push out the silt and loosen and aerate the gravels, providing a supportive environment for trout eggs and fry. The year following an above-average runoff generally results in increased trout recruitment numbers.

For those who are enchanted by high mountain meadows, high-water years are a blessing. These meadows act as huge sponges and retain snowmelt, releasing it gradually during the year. This groundwater recharge is more pronounced in years that follow one or more winters of below normal snow and rainfall.

In a related way, big runoff means big wildflower years and flowers late in the season. If you do your backcountry traveling in August, this will be a year in which you will see the flowers you usually miss by not traveling in July. Birds and other wildlife also take advantage of wetter years. Nesting birds may be able to add another clutch, and other animals will take advantage of increased food supplies.

There are some advantages for the angler, as well. This is a great year in which to explore. Most people are creatures of habit. I tend to fish the same places over the years, but I know that because of the runoff, some of these are going to be problematic for a while this year. What better reason to try somewhere new? Find some places that combine positive runoff factors and have a go at them. Finally, as you suffer through the frustrations of deep, cold water this spring and summer, remember that in the fall, the fishing could be spectacular.

Water Management Information

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power Aqueduct System: http://www.ladwp.com/ladwp/aqueduct/showAqueductMap.ladwp?contentId=LADWP_AQUERTD_SCID

Mono Basin: http://www.monolake.org/today/snow

California and Nevada: http://www.dreamflows.com/flows-canv.php

U.S. Geological Survey: http://waterdata.usgs.gov/ca/nwis/current/?type=flow

California Department of Water Resources Data Exchange Center: http://cdec.water.ca.gov/

Peter Pumphrey