The Golden State is home to a profuse and exciting array of insects that tempt trout and tease anglers throughout the year. Our large state hosts many streams and myriad lakes, most of which offer good fishing during quality insect hatches. Species vary with geography, and insect populations that are huge in one area aren’t to be found in another. Insects that hatch prolifically in the southern part of the state may produce only sparse hatches in the north, and vice versa. Lakes are home to great hatches that are lesser known in rivers. Fast-moving streams host insect populations quite different from slow-moving waters. Consequently, to develop a list of the most important hatches in the state obviously means excluding many contenders.

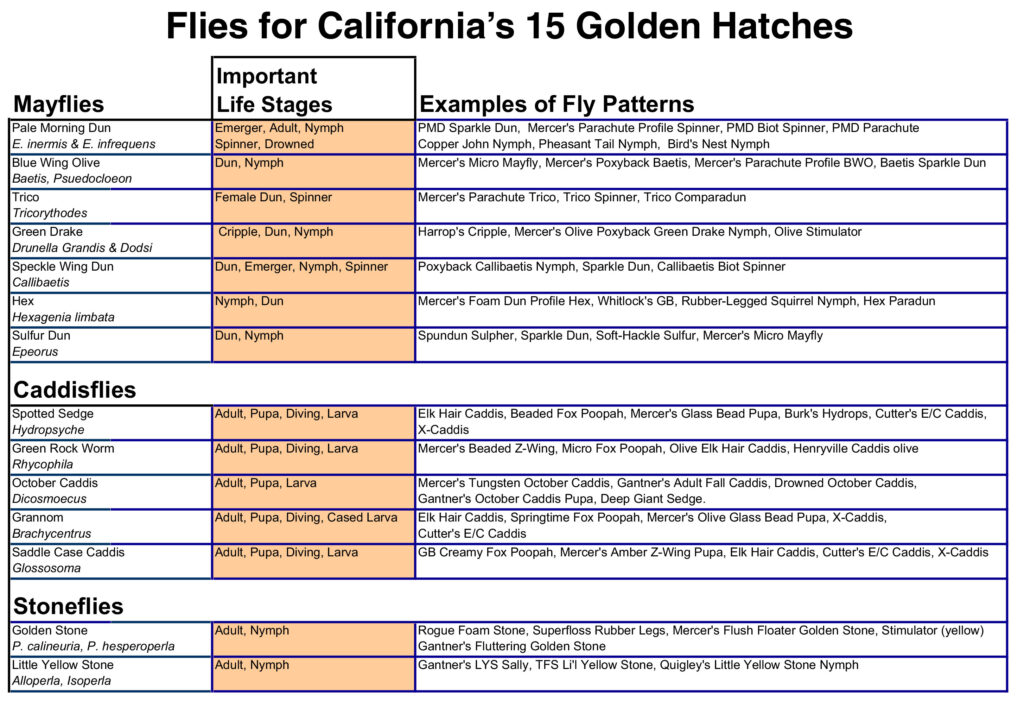

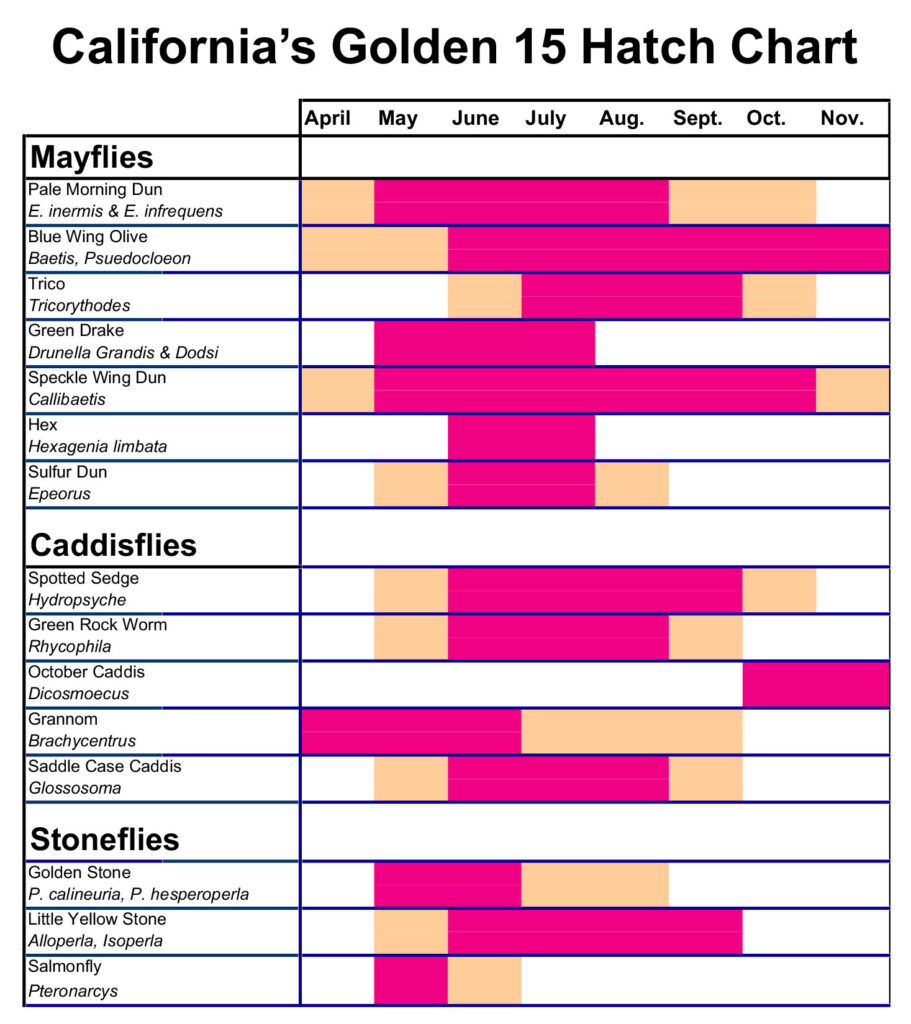

A list of the most important hatches in the state is what California Fly Fisher’s editor, Richard Anderson, asked me to develop, though. In fact, the job assigned me was to select the top 12, not the top 15. I couldn’t do it without leaving off personal favorites. As it stands, the list leaves many strong hatches without proper recognition. But as you’ll see, this isn’t a “Top 15” list, in the genre of David Letterman’s “Top 10” or the New York Times Bestseller List, with the order of the elements ranked in terms of their overall importance. Instead, it’s ordered chronologically, from April through November, the time frame of the general California trout season. The emergence dates discussed are the widest parameters and need to be adjusted for particular waters. The valleys will see the bugs appear early in the time frame, while the mountains will see the same insects later in the year. Although I will present the insects in their common order of appearance, again, this may vary from stream to stream. And in general, slower waters favor the smaller insects, such as the BlueWinged Olive, Callibaetis, and Pale Morning Dun mayflies (the huge Hexagenia being an obvious exception), while faster waters tend to favor the larger insects, such as the large stoneflies.

If I have excluded your favorite emergence, the one that consistently rewards you on your homestream, it may be because this list covers all of California. Hence, more localized hatches have been scratched. This selection was compiled by studying 14 California streams, plus still waters. Also, in this analysis, I have played a little loose and free with genus and species, lumping some similar insects together for clarity and convenience.

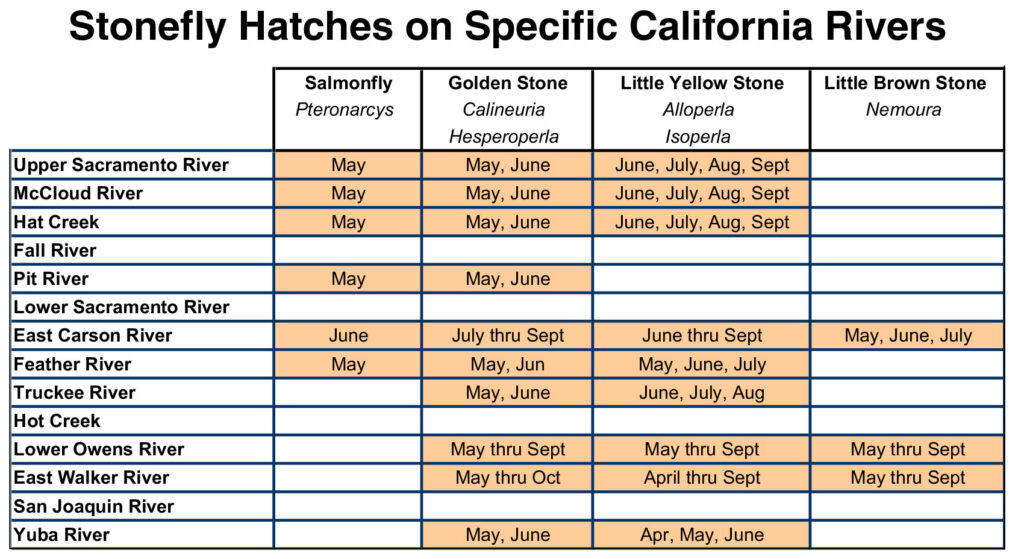

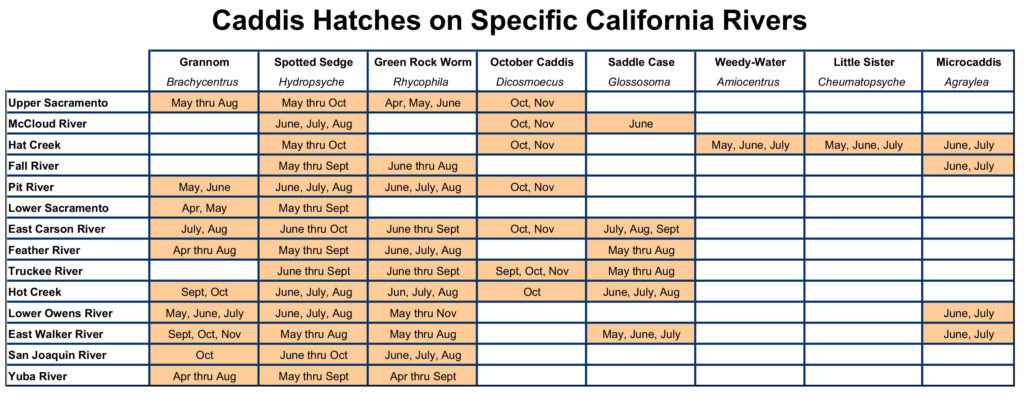

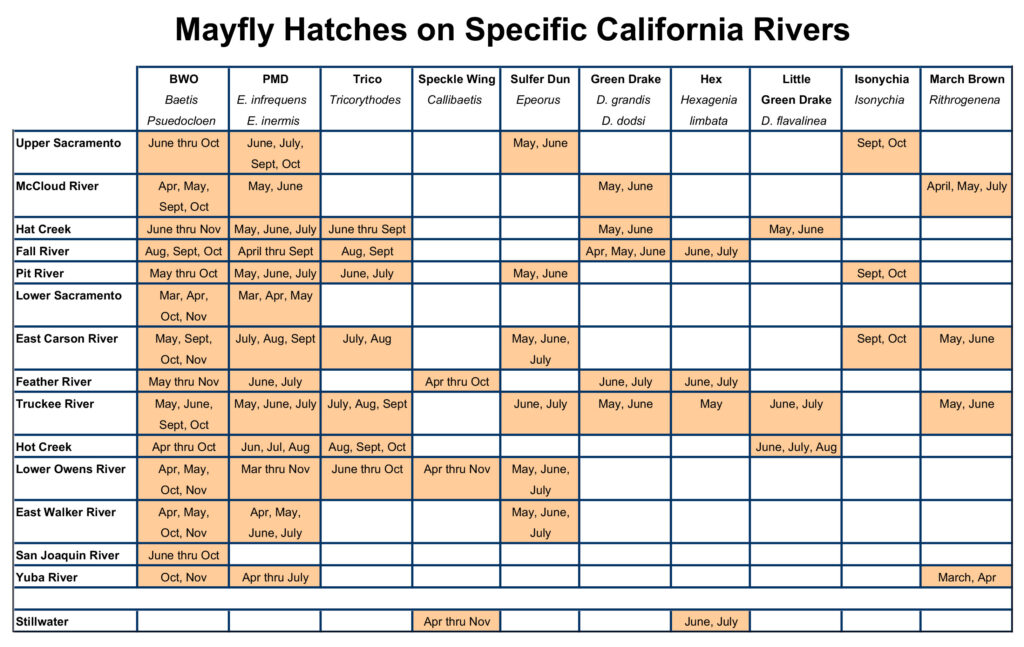

Before discussing the 15 most important hatches, I’ll begin by noting the ones that almost made the list. In mayflies, the March Brown (Rithrogena) produces fine early season action on some streams. The Isonychia and Drunella flavilinea (Little Western Green Drake) hatches also excite fish in some areas, as do Paraleptophlebia (Mahogany Dun) and Ephemerella tibialis (Western Hendrickson) emergences, but their areas of importance were too narrow to make the big list. In the caddis category, the Weedy-Water Sedge (Amiocentrus) and the Little Sister Sedge (Cheumatopsyche) are of great importance on some streams, but not on most. The Microcaddis (Agraylea) is widespread on California waters, but its diminutive size keeps it from being regularly imitated. In the stoneflies, the Little Brown Stone (Nemoura) is important in parts of the southern state, but less so in the north. That covers nine good, though localized hatches that just missed the list. The list also covers only aquatic insects, leaving my favored ants, beetle, and grasshoppers as a separate topic. And the list ignores the midges (Chironomidae), not because they are not important — they are super important — but because they are everywhere, all the time, or very nearly so, and their hatches are ongoing year-round. Most waters you fish in California will be home to midges, and you would be wise to always to carry your midge fly box.

Here are the “Golden 15” hatches:

The American Grannom (Brachycentrus): April through September.

Already commencing their emergence in many streams by April’s trout opener, the early Grannom is the first caddis hatch on most waters. It has a wing that’s dark gray to black over a dark green to very dark brown body, and the insect can be matched by a size 14 or 16 dark caddis imitation. These caddisflies hatch in the afternoon and evening and present both emergers and egg layers at the same time, creating sometimes overwhelming numbers. A dry-fly caddis imitation with a trailing emerger can prove deadly. A second Grannom species hatches in the summer or fall, and although not as prolific as the early hatch, it offers the best opportunity to the angler during the morning and evening egg-laying sessions. This species dives to the bottom to paste its eggs to streambed rocks. The swimming, diving egg layer is a favorite of feeding trout.

Grannom larvae spend most of their time in rectangular, chimney-shaped cases and are frequent trout snacks. The Grannom caddis can be effectively fished with dry adult, emerging pupa, diving adult, and cased-caddis larva imitations throughout much of the season.

The Blue-Winged Olive (Baetis and Pseudocloeon): all season.

The season’s first mayfly is on the water prior to the season opener in low-elevation waters and soon thereafter in mountain areas. Their diminutive size (16 to 20) is more than offset by their prodigious numbers and season-long emergence. Their hatches are strongest on overcast, drizzly days, when dry-fly imitations generally outfish emerger and spinner patterns. The adults tend to float for long periods on the water’s surface, drying their wings, becoming easy and plentiful buffet items for dining trout. Their dull-olive bodies and gray wings cover the waters in the spring and again in the fall, especially on spring creeks and tailwaters.

Baetis nymphs are good swimmers. However, they often tend to drift in the current, making a dead-drift technique the most effective. Adult and nymph patterns are recommended for Blue-Winged Olive hatches.

The Spotted Sedge (Hydropsyche): May through October.

By May, the second major caddis emergence occurs. The Spotted Sedge produces California’s most important caddis hatch, with prolific numbers throughout the season. It appears prominently on all of our noted trout streams. This is a larger caddis (size 12 to 14), with a brown or olive brown body and mottled gray-and-brown wings. Both emergence and ovipositing occur in the late afternoon or evening. This is another diving egg layer, and the sunken adult is a constant and vulnerable trout food. The tan/green larvae are net spinners and are regularly found drifting free in the current. The yellow/tan pupae are best imitated by a tan size 14 fly. All four stages of this bug’s life cycle are important to the angler.

The Pale Morning Dun (Ephemerella inermis and Ephemerella infrequens): May through August on most streams.

Pale Morning Duns provide the most important mayfly emergence in California, based on their abundant numbers, with appearances stretching throughout the summer. They are the predominant mayfly on most of our streams. Hatching from midmorning through midafternoon, these pale-yellow sailboats are best imitated with size 14 to 16 flies. Long, drag-free drifts are required to entice trout to feed freely on the adult. The spinners lay their eggs on the surface and then fall spent, awaiting a death by trout. The olive-brown nymphs become available to trout shortly before the hatch, and patterns for the nymph, emerger, dun, and spinner are all effective fish foolers.

The Speckled Dun (Callibaetis): All season. This is the number-one stillwater hatch (not including midges), occurring all season long on most ponds. Callibaetis mayflies are also seen emerging on slow water streams such as our best spring creeks. With multiple generations each year, overlapping emergences seem continuous and produce size variations best imitated with hook sizes from 12 to 18. With a tan underbody that’s brown/gray above and with mottled gray wings, the adults can be difficult to observe on the water and the spinners impossible to see. Matching the size of the insect is paramount to success. Emergence is typically from midmorning to midafternoon, and the nymph, emerger, dun, and spinner are all effective flies to carry.

The Green Drake (Drunella grandis and Drunella dodsi): May, June, and July.

Green drakes are large (size 8), stout mayflies with a fairly short emergence season and are available only on select streams. They are included here because when encountered, they produce an exciting and trophy-fish-fooling hatch. Appearance occurs from midmorning to midafternoon, and the insect is very vulnerable to trout in three phases: nymph, emerger, and dun. The nymphs are slow, clumsy swimmers and are easily accessible to trout during their tedious swim to the surface. The emerger is quite prone to damage and defects, with many cripples and stillborns offering trout large and helpless protein packages. The duns ride the surface for extended periods to allow their wings to dry, often floating many yards downstream in this vulnerable condition. Spinner falls occur at night and are of little importance to anglers.

The Green Rock Worm (Rhyacophila): May through October.

The Green Rock Worm, a free-living caddis larva (no case), often gets swept into the current to drift long distances in trout-tempting vulnerability. Streams with fast, cold, broken currents over rocky bottoms will have bright-colored Green Rock Worms present. Colors darken to a green/brown on the pupae and darker brown on the adult. Larvae are prone to drift during low-light periods. Hatches normally occur in the afternoon and are sporadic, rather than en masse. Sizes vary greatly, with imitations on hooks from 10 to 14 covering most situations. The larvae, pupae, adults, and diving egg layers are all taken by caddis-munching trout.

The Sulfur Dun (Epeorus): June thru August. Sulfur Dun emergences can be sporadic throughout the day. Their nymphs are seldom available to trout until just before emergence, when they may drift free. Many of the little yellow adults emerge underwater and move to the surface with wings folded back, making a soft-hackle pattern a good imitation. Spinner falls may occur in the morning, evening, or not at all and thus are only occasionally of importance. Insect sizes vary and are imitated with patterns on hook sizes 12 to 16. I’ll often fish the dry fly with a soft-hackle trailing fly.

The Salmonfly (Pteronarcys): May or June. The huge and aerodynamically challenged Salmonfly offers a major mouthful that will entice even the most cautious trout to bang the surface for this entrée. But there is only a small window of opportunity for the angler to enjoy the emergence, so how could I include this short timer here? It inhabits only a few of our streams in large numbers, and its hatches last only a few weeks. (True — too true.) Chasing the elusive Salmonfly hatch has become a cult endeavor for some. The rewards come stingily, but when they come, they’re the top of the sport. The dark brown/black nymphs crawl out onto land to hatch. Hence, the insects aren’t available to trout as they struggle to emerge. The nymphs are available throughout the year, however, and the ponderous adults swarm drunkenly over the water in the afternoons, often the victims of crash landings on the trouts’ table. The fluttering egg layers are prized by trout looking up for stonefly burgers. This sumo-sized insect is best imitated in sizes 4 to 8 in nymph and adult phases.

The Golden Stonefly (Calineuria and Hesperoperla): May through July.

Like their big cousins, the Salmonflies, Golden Stones offer full-course meals to ready trout. Their hatch shortly follows that of the Salmonflies and may overlap. Goldens inhabit more California streams than Salmonflies, and their hatches extend over a longer period of time, up to four weeks or more. The nymphs offer year-round edibles to fish, and the daily adult activity over the water and fluttering dips by egg layers make the Golden Stonefly a more important hatch than the more publicized Salmonfly. A heavyweight, the Golden is imitated by flies in sizes 6 to 8.

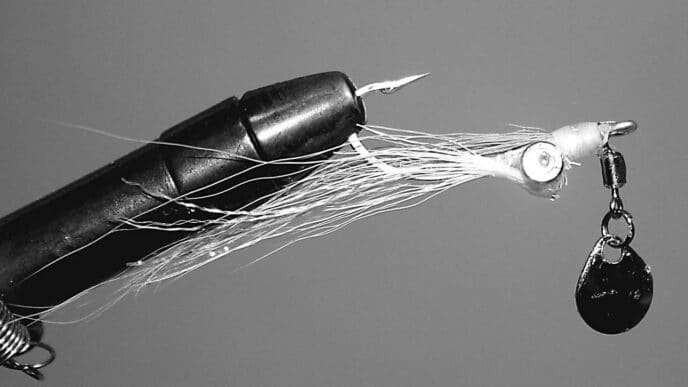

The Hex (Hexagenia limbata): June and July. A burrowing insect, this mayfly on steroids prefers slow-moving waters with muddy bottoms, both streams and lakes. This is a late-evening hatch and lasts after dark. Because the nymphs live in burrows in the mud, they are seldom available to trout except during emergence. Spinner falls typically occur at night and are of little value to the angler. The nymph swims to the surface with an extreme undulation, and copying this up-and-down can improve an angler’s success. A jointed Wiggle Nymph fished with a twitchy stop-and-go retrieve is the way to go. The large yellow dun is best imitated with an extended body pattern in sizes 8 to 10.

The Saddle-Case Caddis (Glossosoma): May through September.

Emergences occur sporadically throughout the afternoon and evening, and this small caddis is often best fished with a dry fly trailing a soft-hackle pupa imitation. The female swims to the bottom to deposit her eggs and is vulnerable in her reascent to the surface. The larvae are case builders, but become vulnerable when leaving one case to build a new, larger model. During this free-roaming period, the cream or pink larvae become a major food source for foraging trout. The tan pupa imitated with a size 14 to 18 fly is dead-ly in the evening, swung across the currents with a twitchy technique.

The Little Yellow Stonefly (Alloperla and Isoperla): June through September.

Before and during the late afternoon and evening hatches, the nymphs actively move toward the shore en masse and are readily available to foraging fish. It is during the late afternoon and evening egg-laying flights that the adult becomes tempting, and splashy rises will signal that the trout are chasing the taildipping females. A fluttering-style dry fly with a lightly weighted nymph trailer can produce solid evening success.

The Trico (Tricorythodes): June through October.

Tiny, but prolific, the Trico is best noted for its midmorning spinner fall, so heavy on some waters that the little carcasses fairly cover the stream, with clots of bodies collecting in eddies and backwaters. The dark-bodied males hatch at night, but the light-olive-bodied females hatch in the wee morning hours and can be important to early rising anglers while the rest of us sleep in and await the spinner fall. On slow, weedy streams, Trico spinner falls tend to be heavy, pulling up even the largest trout to vacuum the hordes of bugs from the surface. Imitated on size 18 to 22 hooks, Trico patterns can be tough to see on the surface, but feeding trout become so rhythmical in their takes that a well-timed, well-placed cast has a very good chance of hooking a trout.

The October Caddis (Dicosmoecus): October or November.

This may be the single most exciting two-to-three week hatch in California fishing. October Caddises can fill the air and blanket the stream during their prolific hatch. The October Caddis crawls and swims out of the stream to emerge. Thus, the real action comes when the adults return to the water for egg laying and eventual expiration on the surface, which occurs in the late afternoon and into the dark. These huge caddisflies, imitated on sizes 6 to 8 hooks, can provide the best dry-fly fishing of the season. The larvae, both in and out of their cases, are a factor only during June and July, when they are likely to be found drifting in the currents. The pupa is available to the trout during the migration to shore and during the occasional event of a midstream emergence.

The goal of any knowledgeable fly fisher is to be on the water at the right time and to present the correct fly properly to bug-hungry trout. To accomplish this, the angler needs to know which insects are most likely to appear and what characteristics of those bugs must be captured by the fly in order to fool trout. The astute California angler will know the hatches that are expected in the spring, summer, and fall and will carry proper representations of those insects. Understanding the 15 hatches that we have discussed will ensure that you are prepared for about 90 percent of the important hatches you will face on our trout streams.