I’ve been fishing with Peter Syka, my latest guest at The Roost, for over 40 years. Nobody needs to listen to a couple of old farts reminisce, yet it’s worth noting, by way of context, that a friendship this long dates back to an era when, say, you could still grill a pair of Yellowstone cutthroats while meandering about the park. In the San Diego and Baja California surf where Peter and I were lured into uncharted waters, the sport of saltwater fly fishing was not so much an anomaly as it was a kind of secret witchcraft concocted by bands of rogue anglers who, in their own isolated haunts, had fallen under the spell of midnight jinn or other potent spirits.

Time and experience, of course, are the sport’s two great teachers. Which is why I feel especially lucky to have an old hand like Peter agree to drop by The Roost and share what he’s been tying lately for the surf — specifically, what he uses these days for targeting barred surfperch, day in and day out, the species the Southland surf angler can expect to catch between far-flung encounters with yellowfin and spotfin croakers, sandbass, corbinas, halibut, or other more illustrious prey.

Savvy readers may question the intent. Does anyone really need a perch fly? Can’t you catch them on anything?

Peter dismisses the question with a patient smile. This late in life, he’s adopted a far-reaching generosity toward a kind of unfathomable ignorance and outright stupidity that once threatened to drive him mad. An important aspect of our friendship has always been his reluctance to buy into my own high-pitched shenanigans and half-baked schemes. He was the first person to point out to me that my second book, the screwiest of jury-rigged novels, was “unreadable.” A lifelong scientist versed in the pop culture and political absurdities of the past half century, he asks little of others beyond a willingness to pay attention to what’s going on. Adjusting a Padres cap above the shadowlike reach of his still-dark and all but conjoined eyebrows, he reminds me that when he and I first tried perch fishing near home, flush with the big streamers and burgeoning baitfish tactics we had done so well with in the Baja surf, we made little, if anything, happen.

“Then I tied up a bunch of Skykomish Sunrises with bead-chain eyes,” says Peter, “tied them on, like, a number 4 regular 3407 Mustad hook — and one day, in one of those rips at Black’s, I started catching perch until I realized ‘Okay, this is how it happens.’”

He’s been making discoveries like this for as long as he’s fished. Still, many anglers refuse outright to fish for perch, as though the species were somehow beneath them, unworthy of their efforts and time. I’ve heard Peter wonder, as well, if he’s ever going to catch something besides “another damn perch.” But the key to all of this, especially when surf fishing, is keeping your fly in the water. If you do not catch perch, it means you are going to end up not catching anything at all.

The latest stage in the evolution of Peter Syka’s perch fly, the Trilobite, has fooled all of the glamour species available in the Southland surf. Like most experienced surf anglers, however, Peter knows that the fly pattern is not what’s going to get you your next spotfin or halibut or maddeningly spooky corbina. But whatever the pattern, it will be a fly that quickly penetrates the strike zone and offers, in Peter’s words, “something that fish will see and eat in a turbulent, foamy, and sometimes murky environment.” Before claiming a name for the fly, Peter once described the Trilobite to me as his “Hare’s Ear for the surf ” — a generic pattern that, regardless of size or color, covers three out of four flies he ties for the surf, flies that fish don’t refuse if you find them.

The Trilobite, explains Peter, is named for “the extinct arthropods, a class of animal that lived for about 270 million years, managed a wide array of sizes and functions — grazers, predators, filter feeders — while retaining an easily recognizable form.” The word “trilobite,” adds Peter, means “three-lobed.” “The flies I’ve been tying and using are really a simple assembly of three components: eyes, hair, and legs.”

At the vise, Peter handles himself, the tools, and his materials with the quiet attention to detail of someone who’s been practicing his craft a long, long while. But there’s more to it than that. Decades ago, when we both first got out of college, Peter made a living operating on rats, part of the research done at the lab where he worked; for the past two or three decades, he’s operated on a scale that goes right down to the tiniest components of life. His skill as a tyer reminds me of the time I fished with a retired dentist in Baja; after admiring a collection of elegant saltwater patterns he had tied, I realized I shouldn’t be surprised. “I guess if you’re a decent dentist,” I noted, “you ought to be able to tie flies.”

I’ve tied next to Peter up and down the length of Baja and throughout the West. I’ve tied on picnic tables, at vises hooked to beach chairs, in the front seats of nearly a dozen different trucks and vans, one vise hooked to the steering wheel, the other to the open door of the glove compartment. Tying in camp or on the road, in anticipation of the next session on the water, has been such an integral part of our fishing trips that I’m surprised when I come across guys who don’t indulge in the practice — the luxurious delight of carefully constructing three or four specimens fashioned precisely for the showdown ahead.

I suppose you could drink, instead.

The trilobite, anyway, reflects a school of fly tying practiced by what I like to refer to as the “imaginative angler.”

Like many tyers, especially those of us who tend to take existing patterns and turn them into flies for our own specific fish and waters, Peter rarely settles on precise recipes for any of his flies. Experiment and improvisation serve him as much at the vise as they do on the water. He’ll suggest — but he generally avoids making claims. Asked about hooks for the Trilobite, Peter lists a number of different Gamakatsus. But then: “If I only had one hook to use, it would be a size 2 SC-15. That size seems to be a compromise that allows you to put enough material on the fly to make an impression in the water while still being small enough to fit inside a perch’s mouth.” Likewise each of the three essential components of the Trilobite — eyes, hair, and legs: “I have used and will probably still feel free to use whatever materials I come across that will give me the desired profile and action in the water,” says Peter.

What this means is that the Trilobite is not so much a pattern as it is an effective template that adapts to the wide variety of conditions one finds fishing in the surf. If you’re paying attention, you’ve probably also made this connection: an adaptable template is how a class of animals can hang around for 200 or 300 million years, give or take a few million either way.

“For hair,” says Peter, “I’ve used bucktail, calf tail, squirrel tail, fox hair, and coyote hair.” For the eyes, he prefers black nickel dumbbell beads, but he’s used black, chrome, and bronze plumbing chain, plus, he says, “those expensive Real Eyes, which I am not sure offer any advantage in 95 percent of the situations that I’ve fished, as well as those heavy painted-lead dumbbell eyes, which confer the compounding disadvantages of expense, chipping, and the tendency to knock me hard on the back of my head while casting.”

Of the countless options for rubberleg material, Peter likes the limp, squarecut strips with subtle markings or reflective flake, a preference based on nothing more, he says, than the way the material ties and how it looks. But he’s under no illusions that any of these details will make or break the fly. “I’ ll tie the Trilobite sparse, I’ll tie it dense. A single color or shade, or two colors — dark hair, bright legs. Red is a go-to color for perch, and I always have some in my box, but I am more likely to fish a drab or dark fly than anything bright.”

After 40 years, I don’t have to ask Peter why. His preferences and hunches belong to a long career of patient observation in the ever-changing and shape-shifting environment of the surf. Nobody on the beach has any final answers. It’s always been a game of long shots.

“I could go on and on how to fish the things,” says Peter, rising from the vise. And for a moment he seems tempted to start. “Sinking shooting heads, 6-to-9-foot leaders, put the fly down to where the fish are. It might not be that deep, maybe two or three feet, but often there isn’t a lot of time for it to sink into the strike zone while the fish are there.”

Still, there’s too much to tell. Where to begin? A fly like the Trilobite would be a good bet. Plus a tide book. And learn how to read the water.

After 40 years, you’ll probably have some sound opinions, too.

Materials

The materials listed below were used for the perch flies I tied and photographed after seeing a selection of Peter Syka’s own Trilobites. The tying instructions come directly from Peter.

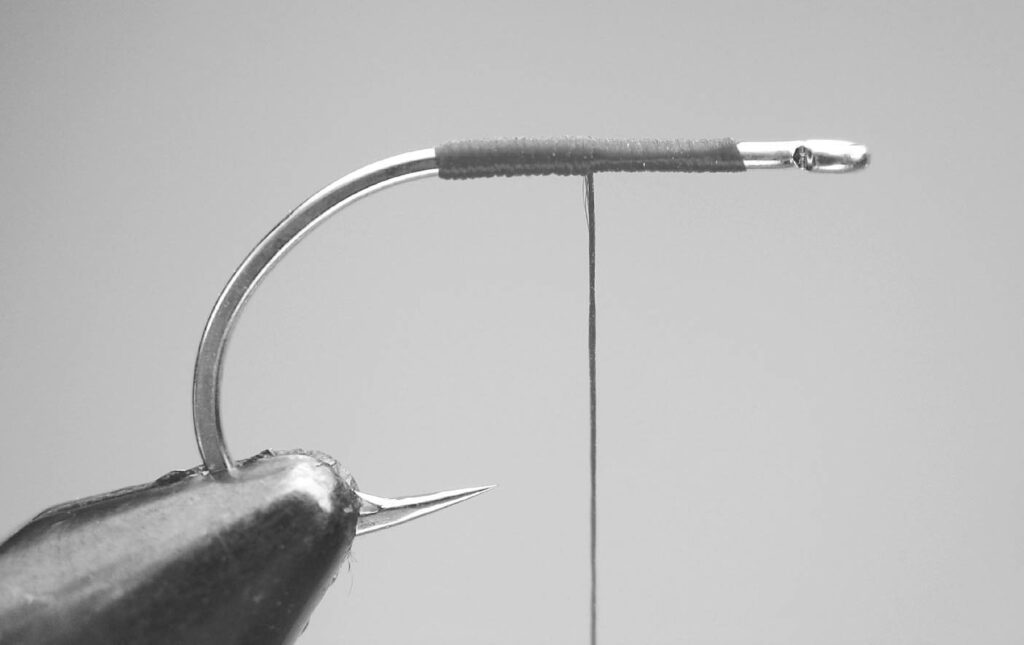

Hook: Gamakatsu SC-15, size 2

Thread: Red Danville’s 140 denier Waxed Flymaster Plus

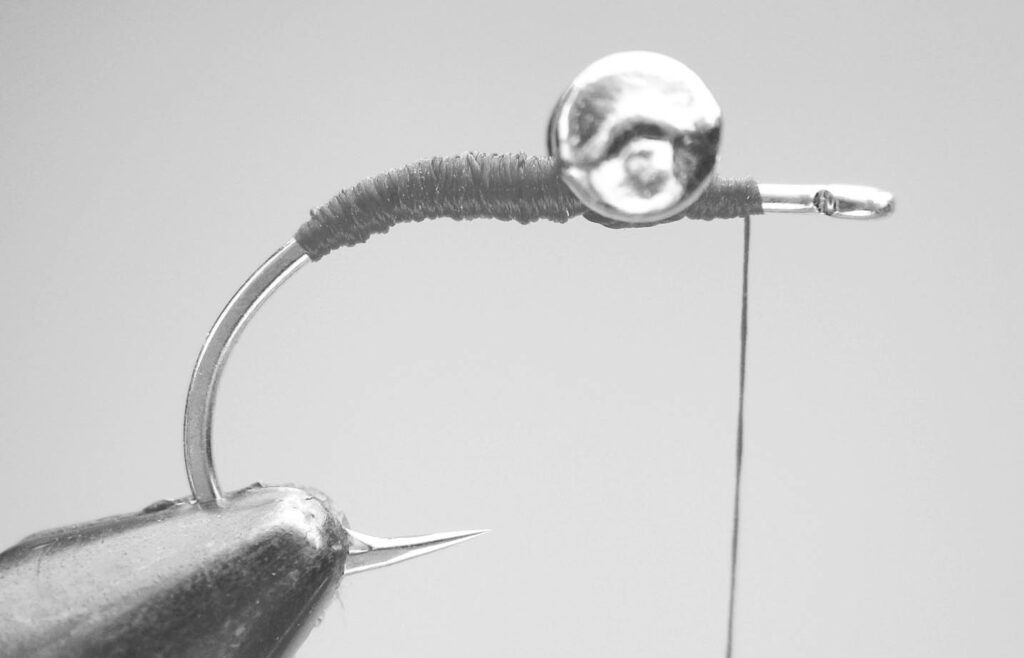

Eyes: Dumbbell lead eyes, small (1/40 oz.)

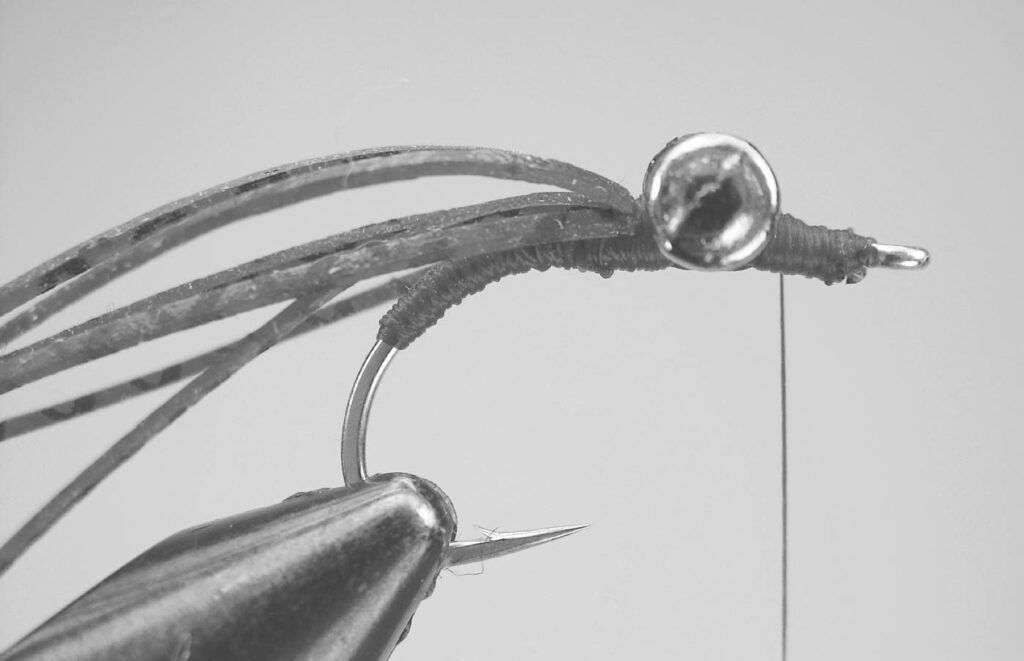

Legs: Red Grizzly Legs

Hair: Red ram’s wool

Tying Instructions

Step 1: Secure the hook in the vise and wind on a base coating of whatever color your legs and body are going to be.

Step 2: Tie in the dumbbell eyes. Give yourself plenty of room between the dumbbells and the eye of the hook. For shorter-shanked hooks such as the SC-15, I put the eyes just forward of the halfway point of the shank. With larger, longer shanked hooks, I put the eyes about one-third of the way down the shank. You’re going to need room to tie in bulky materials without covering the hook eye.

Step 3: When the eyes are in, fold a piece of rubber leg in half and tie it in at the start of the hook bend. Keep wrapping the thread to even out or bulk up the body a bit, then whip finish it behind the eye. I use a cyanoaclyate glue (Krazy Glue) to cover the body and the wraps, anchoring the dumbbell eyes. When I’m in production mode, I cut off the thread after the whip finish, treat the body and eye wraps with glue, then stick the fly in progress in a chunk of foam and start another fly.

Step 4: After the body wraps are dry, put the fly back in the vise, start a few wraps of thread in front of the eyes, and tie in the rubber legs. Most of the time it’s three rubber legs, folded in half, with the bundle of midway loops tied in just ahead of the eyes. Pull the legs over the “handle” of the dumbbell, wrap the thread a couple of times behind the eyes, bring the thread wraps in front of the eyes, and after trimming the excess rubber-leg material, tie off and whip finish the head. Cut the thread again and put a dab of Krazy Glue on the rubber legs where they stretch across the midsection of the dumbbell, as well as on the whip finish. These flies are going to be spending a lot of time getting dragged across whatever bottom you’re fishing on (notice I said “on” as opposed to “over”). That dab of glue will help the fly last longer.

Step 5: When the glue has dried, rotate the fly (flip it over, hook up, if your vise is fixed) and tie in the ram’s wool wing. I want to have the thread match the color or shade of the wool. When the wing is secured, whip finish the head and, yes, saturate the head with Krazy Glue.