Scott Sadil, our new columnist for “At the Vise,” is no stranger to readers of this magazine or to readers of fly-fishing periodicals and literature in general. His work has been published in Gray’s Sporting Journal, Fly Rod & Reel, The Drake, Fly Fisherman, and American Angler, among others. His books, all well-regarded, are Angling Baja (memoir), Cast from the Edge (novel), Lost in Wyoming (short story collection), and Fly Tales (essays).

It was Scott’s thoughtful musings in the latter book, on fly patterns and the lessons they teach us, that has brought him to this particular position in California Fly Fisher. Scott’s perspective on flies and fly-tying is a particularly pragmatic one. Yes, Scott says, “a good pattern, well tied, makes a difference.” Nevertheless, he adds, “fundamental to my teaching about the sport is my long-term observation that too many anglers — especially less experienced ones — feel the Right Fly is the essential answer to the problem of not catching fish.” As Scott discusses below, other skills are critical, as are the insights that come from time on the water and the reflection that it spurs.

Just inside the door to the Tyers’ Roost hangs a sign that grabs the attention of every fly fisher who enters. “Your fly doesn’t matter.”

Nobody’s sure who painted this peculiar piece of art, or if the mayflies fluttering about the fairly sophisticated rendering of the front of a pair of Levis were part of the original watercolor or added later. At some point, it became the custom at the Roost to have first-time visitors add their names to the sign and, if so moved, embellish it with the aid of pens and pencils and fine-point Sharpies standing inside the bottom half of a dried gourd hanging from a lanyard affixed to the sign’s frame.

That about covers the “Rules of the Roost.”

Today, the sign serves as a kind of guestbook, a record of both regulars at the Roost and fly tyers who drop in now and then or once and never again. Still, there’s also the sense that a signature acknowledges the sign’s unsettling message — and sometimes, late at night, after the tying’s finished and spirits descend from the shelves, someone will feel moved to address the matter directly, forgoing the usual slippery ironies and rhetorical sleights of hand, an appeal to reason that, if left unchecked, we know from experience can lead to fistfights, backbiting or, at the very least, censure on somebody’s Facebook page. Your fly doesn’t matter. Is it a joke? A sorry shot taken by someone with a sophomore’s sense of humor? Or is it a suggestion for tyers at the Roost not to take themselves too seriously — a reminder to check our egos at the door, because, after all, the only thing going on here is fly tying, and say what you will, there’s just as much at stake practically everywhere else we turn besides our neighborhood rivers and beaches and trout streams? Or could it possibly be that the statement is essentially. . . true? It’s not the fly that catches fish, but instead, the fly fisher’s presentation — the stalk, the cast, the drift, the strike — these and the very many other intricate and elegant and subtle skills that anglers of a certain bent will argue outweigh the importance of the fly pattern by about a hundred to one?

Yet if that’s the case, who are all these fly tyers?

And what are they doing here at the Tyers’ Roost?

Immediately past the sign in the entryway of the Roost you notice the light — a big picture window filled with sky, a snow-capped mountain, the sense of a wide river below the rooftops and trees. In a corner beside the window stands the requisite woodstove; across the room a modest kitchen, the appliances there the only electrical devices in view besides lighting and lamps.

Furniture? What furniture?

Instead, we face a tidy arrangement of half sheets of plywood set atop pairs of sawhorses and surrounded by assorted straight-backed chairs, as in the seating area of a cozy hipster coffee shop — or when your parents from the valley have set the stage for their monthly bridge group.

And at the tables this evening, five tyers at work at five vises, a modest crowd at the Roost, the pitch of their work an odd, but not inexact reminder of the subtle movements of the nymphing trout that the flies they are tying this very moment are meant to fool.

Here’s one way a session at the Roost can work.

This coming weekend, Mr. Kelly is scheduled to spend two days in a frothy, sheer-walled river canyon where nymphing with big, dark bugs — usually of the stonefly persuasion — is the go-to m.o., at least until something more obvious happens, attracting the trouts’ attention and, tonight, he hopes, our own.

Everybody has a favorite stonefly nymph, from young Gabe’s simple Woolly Bugger to Fred Trujillo’s sparkpluglike rendition of the classic Kaufmann’s Stone. But someone else recalls a trip to one of the all-time gnarly canyons in the wide reaches of the West, and following a couple of e-mails and an Internet search, he’s

got his hands on a recipe for that famed peacock-herl stone, the 20-Incher Stone, a fly he remembers using to such good effect, dipping it along the edges of the brawling canyon runs, where brown trout slipped from under the shadows of rocks, each spotted body as thick as the head of a moray eel.

Only now that he thinks of it, the fly wasn’t exactly the 20-Incher. Instead, the fellow he fished with had tweaked the pattern for the usual private reasons, settling on a version he now calls Kaylee’s Stone, an attractor nymph named in honor of his pretty young daughter.

So it begins.

Everyone’s got opinions. Everyone’s got habits, manners, ways — some proven, some as far out as whalebone stays. Some changes made to a well-known pattern such as the 20-Incher are simply a matter of materials at hand; more tyers than not pull from their own stashes of hooks, beads, dubbing, wing-case material, materials for legs. Not that anyone won’t share: at the Roost, what’s mine is yours. At the same time, you bring it, you share it — at least while any bit of it lasts.

But tonight, what everyone agrees on is the appeal of the long peacock-herl abdomen of both the 20-Incher and Kaylee’s Stone. Does anything else about these big nymphs really matter?

The discussion heats up. Peacock herl is hardly a new idea. Yet at a time in the sport when so many anglers believe their flies need to replicate what they see when they look at an adult insect or the nymph, there’s a tendency to reject proven materials simply because the color or some other visual attribute seems wrong. In the rush to fish strictly imitative patterns, anglers often ignore or forget about the alchemy of classic patterns, the way in which traditional materials combine to create patterns that, for no clear reason, simply work. Many anglers understand and readily accept the notion of classic dry-fly attractor patterns — the Royal Coachman, the Trude, the Humpy, even the generic Adams — but they turn away when the same ideas are applied to their patterns for nymphs and emergers.

Finally, someone recalls a week thirty years ago in New Zealand, fishing nymphs upstream, two at a time, using a fly so simple that the guide had no name for it but “Copper and Peacock” — an ancient pattern that needed little tweaking to become a Leadwing Coachman, Prince Nymph, My Favorite Terrestrial, or other peacock-herl flies that have been rolled out and championed across the decades, one after the other.

But what about the rest of Kaylee’s Stone?

We go at it our separate ways. It’s not as though anyone disagrees about other aspects of the fly or how it should be tied, but only, one suspects, that nobody feels strongly one way or the other once that bottle brush of herl’s been wound. For the rest of it, you could just say “complete the nymph,” and nine tyers out of ten would know exactly what you mean and how, more or less, to go about doing it.

Which may be what the sign in the entryway of the Tyers’ Roost is really trying to say. Your fly doesn’t matter. By the end of an hour of casual tying, we’ve got close to two dozen Kaylee’s Stones puddled on a table, no more than two of any one of the versions quite the same. Where the hell did that purple peacock herl come from? And yet, if we all just closed our eyes and randomly grabbed the same number of flies we just tied, not one of us would hesitate to fish the flies we ended up with.

Your fly doesn’t matter. Most of us at the Roost are pretty good at this. Most of us have a lot of experience both at a vise and on the water. Most of us are fairly clever when it comes to mimicking or tweaking somebody else’s flies. Yet there comes a point in most tying careers when we recognize that say what we might, the flies we tie don’t give us one bit of an advantage over the flies tied by others.

Your fly doesn’t matter. That’s a good way to think about it — even if none of us believes it.

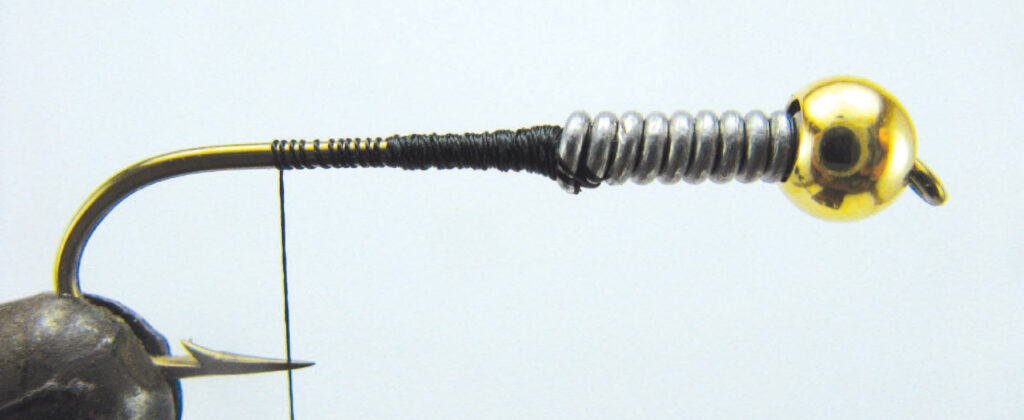

Materials for Kaylee’s Stone (Todd Miller)

HOOK: Umpqua U301 or similar, size 6 to 8

WEIGHT: .030-inch lead wire, 10 to 15 wraps

THREAD: Black

BEAD: Gold 3/16-inch or 1/4-inch tungsten

TAIL: Brown goose biots

RIB: Gold French tinsel

UNDERBODY: Dark green dubbing

ABDOMEN: Peacock herl

WING CASE: Turkey tail feather

THORAX: Gray or tan dubbing

LEGS: Black or brown rubber, two pairs

The hardest part of tying a big nymph — or perhaps any big fly — is getting the proportions right. With all that room on the hook, you think it ought to be easy, when in fact, what can happen is that you end up making a bigger or more obvious mistake instead of striking the appropriate balance for the fly’s forward and aft components.

Tying Instructions

Step 1. Slide the bead onto the hook. Clamp the hook into the vise. Wrap lead wire around the forward third of the hook and jam it into the back side of the bead. Start your thread and build a slight taper between the lead wire and the hook shank, securing the wire tight against the bead.

Step 2. Take the thread back to the bend of the hook or just above the point of the hook. Tie in a pair of goose biots.

Step 3. Secure a length of tinsel at the root of the tail. At the same point, attach four to six strands of peacock herl. Add the dubbing material to the thread and build the underbody of the abdomen, ending at the back of the lead-wire wraps.

Step 4. Wind the peacock herl forward to create the abdomen. (Normally, I would create a dubbing loop for a body made out of peacock herl, but I trust the ribbing to keep things from unraveling, even after a couple of encounters with toothy trout.) Don’t worry if small bits of the underbody dubbing material show through. Follow with several turns of tinsel ribbing, also spiraled forward.

Step 5. For the wing case and legs, first tie in a slip of turkey tail by the tips, dull side up. Wrap the thread back over the turkey slip to just about the mid-point of the fly. Then tie in a length of round rubber-leg material. Create a beefy thorax with plenty of dubbing wound forward over the lead wraps.

Step 6. Tie in a second set of legs. Pull the turkey-slip wing case forward and secure it directly behind the bead. Clip the excess material and finish with several wraps of thread and your favorite whip finish directly behind the bead.