Editor’s note: We first published this article 15 years ago, in our November/December 1996 issue. Because it discusses Joe Kimsey’s role in the evolution of upper Sacramento River trout flies, it seems appropriate to run it again, with a few slight edits to reflect changes that have since taken place….

The homespun flies of the upper Sacramento River bring back my childhood so fast that the reaction could cause whiplash. They return me to a time of innocence, when I was seduced by the woodsy images found in outdoors catalogues. I would slowly flip through their pages and imagine myself a country gentleman fishing a willowy bamboo rod and, at the end of a silk line and gut leader, perhaps a Parmachene Belle, McGinty Bee, Kite’s Imperial, or Invicta.

But there’s fantasy, and there’s reality. To a 10-year-old kid who financed his fly tying through window washing and lawn mowing, obtaining adequate materials required much sweat and not a little ingenuity. I learned to create flies out of anything I could get my hands on, with Mom’s sewing kit and the neighborhood pets playing prominent roles as suppliers. Because our cat and the household drapes were both regular sources, it amused me how the one would invariably get the blame for shredding the other.

Although my flies didn’t look like much, they were the scourge of local sunfish. This success let me develop a healthy cynicism toward tradition that still influences how I see the world. Vanquished are such doctrinaire assumptions that lead otherwise rational fly fishers to believe they need the “urine-stained fur from the underbelly of a female fox” to tie a proper Light Hendrickson.

Perhaps that’s what I like about the flies that were developed for the upper Sac. They show a startling originality that seems unencumbered by the strictures of traditional fly-tying and fishing practices. Each fly has a real person and story behind it (some lost, some not), and each proves that necessity, always the stern mother of invention, serves also as a darned good fishing partner.

The First Ted

Maybe the upper Sac isn’t one of those storied Catskill streams where legends such as Theodore Gordon first popularized fly fishing in America. But the river has a few legends of its own.

The first fly-fishing guide on the upper Sac was an Indian named Ted Towendolly. (The Wintu name is Tauhindauli, and there’s now a park bearing this name along the river in Dunsmuir.) His people, the Wintus, lived along parts of the Trinity, Sacramento, and McCloud Rivers. As far as we know, in the 1920s, he developed the first flies designed specifically for the roiling waters of the Sacramento — the Bomber, the Spent Wing, the Peacock, and the Burlap. In so doing, Ted started a local tradition of fly tying with common materials that remains to this day.

Flies in the Towendolly series are all tied on size 8 Mustad 3948A hooks with an underbody of 10 turns of .025-inch lead wire. Though obviously designed to sink quickly, each pattern is tied with stiff dry-fly hackle instead of the softer feathers usually reserved for wet flies. The stiff hackle affects the flies’ motion in the river’s current and may be partially responsible for their effectiveness in taking trout.

The Bombers have tails of grizzly hackle, black or reddish-brown acrylic yarn bodies, and a grizzly hackle wound dry-fly fashion at the collar. The Spent Wings are exactly the same as the Bombers, with the addition of grizzly hackle wings standing upright from the collar in a V shape, like a traditional dry fly. The Peacock and Burlap are virtually the same patterns as the Bomber, except they use peacock herl or burlap, respectively, for the body. Precious little is known of Ted Towendolly. Records indicate that Grant Towendolly, the last Wintu shaman, lived with his family along the river at Soda Creek. Ted may have been his son, but information is sketchy. No one seems to know where Ted Towendolly came from or where he went. One thing is clear: At some point, he met Ted Fay and introduced him to his Sacramento flies. It was serendipitous. Fay was to become a popular guide and fly-fishing legend along the river for the next thirty years.

The Second Ted

Ted Fay moved from Oakland to Dunsmuir in 1951, where he and his wife Vivienne purchased the Lookout Point Motel. Although the motel was eventually torn down to improve road access to Interstate 5, Fay’s free guide service for motel guests drew many anglers to the area for over twenty years. In the beginning, Ted purchased his flies from Ted Towendolly. But Ted Fay also made his own contributions to the upper Sac fly series. The Caddis Larvae, the Maggie, and the Cro Fly were Fay additions.

For a time in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Fay’s fly patterns were hot items — so much so that “authentic” Ted Fay flies began to appearing on the shelves of other fly shops. In an effort to differentiate his ties from the copies, Fay began using size 9 hooks. When this unusual size was discontinued by Mustad, Fay went back to his traditional size 8s.

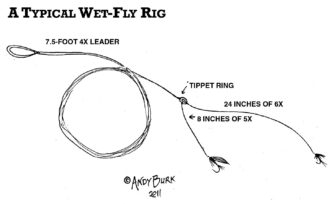

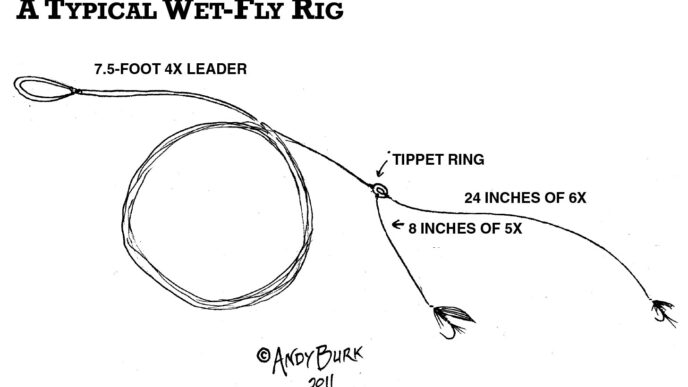

There is some debate over which Ted actually devised the now-accepted shortline, weighted-fly tactic known as “shortline nymphing.” Fay popularized his version of the pocket-water technique, which usually involved two flies, one tied at the end of the tippet, the other some distance above as a dropper. Perhaps it’s just fancy on my part, but I’ve always considered the possibility that Ted Towendolly adapted the technique from ancient Indian methods and then taught Ted Fay. The Wintus used to tie bone hooks to fishing lines fashioned from the sinewy bark of certain streamside plants along the Sacramento. Baited with salmon eggs, the hooks were gently dropped behind spawning redds in the hope of catching a greedy trout. Nothing has been documented, but it’s easy to imagine how one could evolve into the other.

The Fay technique is straightforward. With no more than two feet of fly line beyond the end of the rod, he would drive the nymphs down into the current slightly upstream of a pocket suspected of harboring trout. Keeping the line and leader taut by pointing the rod up and moving it downstream at the same speed as the current, he would watch the leader for any unnatural movement, setting the hook if the leader stopped, twitched, or moved from side to side. This technique is still used virtually every day of the season to catch wary upper Sac trout.

A simple tie in the Bomber tradition, Fay’s Caddis Larvae has a black hackle tail, a burlap body with yellow yarn ribbing, and a stiff black hackle wrapped dry-fly fashion at the collar.

Although the Maggie is not a dry fly, it is the only pattern in the series lacking lead wire. Fay used the Maggie to mimic an October Caddis emerger, fishing it on a dropper just below the surface during the autumn. The pattern has a flared elk hair tail, burlap body with orange yarn ribbing, a grizzly hackle, and an elk hair wing tied vertically at the collar. The head of the fly is finished with fluorescent orange thread.

The Cro Fly was actually created by Ted Fay’s friend Frank Crosetti, who died in 2002. An ardent angler, Crosetti played shortstop for the New York Yankees from 1932 to 1948, then coached third base for the team until his retirement in 1968. “The original pattern had peacock wings,” Crosetti once told me. “I gave it to Ted to copy, but he changed it.” (Fay’s version had no wings.) “I kept asking him, ‘Why not call it the Crosetti Fly? It would sound better.’ Ted and I fished together quite a bit. Now if I don’t fish with two flies, I feel naked.”

The Cro Fly has a ginger hackle tail, yellow chenille body, ginger hackle palmered through the body, and a strand of black chenille brought over the top of the fly and secured to the collar.

The Fay era came to an end with Ted’s death in 1983. There is a memorial to Ted Fay, the “Sage of the Sacramento,” alongside the river in Dunsmuir City Park.

Smokin’ Joe

If you think fly fishing these days lacks its share of characters, the late Joe Kimsey will disabuse you of your misconception. When Joe took over the Ted Fay Fly Shop, he carried on the tradition entrusted to him by adding his own style and contributions to the lineage of upper Sac flies.

While talking to Joe in his shop one summer, I witnessed what I’m sure must have been a familiar scene. A customer walked through the doorway and inquired enthusiastically, “Where are the fish?”

“In the water!” Joe replied in a blink. “What can I get them on?”

“Mostly dynamite and hand grenades!” came the answer.

As the two got down to serious conversation, I wondered whether the walls would have collapsed if Joe’s responses had been any different.

After retiring from a military career, Kimsey started guiding for Ted Fay and working in his shop in 1973. Following Fay’s death, Kimsey moved the shop to the Garden Motel on Dunsmuir Avenue, which became the Acorn Inn. (The shop, with a different owner, has since relocated to downtown Dunsmuir.) Joe’s contributions to the fly series were the Larry, Mary, Leah, and Emu patterns.

The Larry and Mary flies were named for Larry and Mary Green, close friends of Joe’s. Larry, a well-known fishing writer and an outspoken advocate for the upper Sac’s fishery after the disastrous Cantara Loop chemical spill, passed away in October 1994. “Larry came up with the pattern,” said Kimsey, “and it’s a darned good fly, too.”

“Larry and Mary both fished,” Joe recalled with a smile, “but it was always Shasta [their dog] who did most of the fishing.” Mary Green is still very much alive and attended Joe’s funeral. When asked how his friends got the lofty distinction of having their own upper Sac fly patterns, Kimsey responded in typical fashion, “Well, I had to call ’em something.” The Larry sports a short black marabou tail, a copper wire butt, peacock body, and black hackle collar. The Mary has a yellow acrylic yarn body, brown hackle and tail, and a black thread rib.

Of the Leah pattern, Joe said, “It’s a humdinger, made out of a burlap sack.” The pattern also calls for a brown hackle tail and collar. “Leah’s an old girlfriend of mine,” he added, “but we’re no longer on speaking terms.”

The Emu fly was a Joe Kimsey creation that was eventually dropped from the traditional upper Sac series. Bob Grace, the current owner of the Ted Fay Fly Shop, recalls that Joe’s source of emu feathers dried up, so the pattern went away.

Over the years, other patterns have been included in the upper Sac series, but were dropped due to lack of effectiveness. Under the watchful eye of Joe Kimsey, subtle changes were made in an effort to maximize each fly’s productivity. But the patterns also remain true to a rich and intriguing idiosyncratic tradition. Too true, perhaps. “Get after Kimsey,” Frank Crosetti once told me, “to name it the Crosetti Fly.”