One of the most wonderful, yet most misunderstood elements of fly-fishing tackle is monofilament. Much of the confusion stems from marketing hyperbole and the wild claims of almost magical qualities attributed to various manufacturers’ products. “Filament” is a word meaning “thread” or “strand.” “Monofilament” is a fancy five-syllable word that means “a single strand.” Whether it be a strand of nylon, a strand of fluorocarbon, or a strand of polypropylene, it is all monofilament.

In the process of making monofilament, chunks of the parent material (primarily nylon or fluorocarbon) are melted, and secret additives are included to enhance or mitigate certain chemical properties. The molten goo is extruded through small nozzles, then cooled in vats of compounds such as silicone and Teflon. The result is stretched, chemically treated some more, then reheated and cooled. Some companies bombard their monofilaments with gamma radiation or subject them to high pressure. The entire process can be exquisitely manipulated to temper the monofilament and control properties such as hardness, suppleness, stretch, water absorption, and tensile strength. Increasingly, monofilaments are extruded with a core and a shell of slightly different characteristics. These are incorrectly hailed as “copolymer” lines, when in fact, virtually all nylons are copolymers. Some monofilaments have a pliable core with a hard shell for added abrasion resistance, while others are constructed exactly the other way around so that knots can get a better grip. What this all boils down to is that the production process for monofilaments is so complex and the resulting products so diverse that most blanket statements regarding the properties of nylon versus fluorocarbon are largely meaningless. One blanket statement that does hold true, however, is that fluorocarbon is virtually inert and is not degraded by ultraviolet light. Nylon, on the other hand, is directly affected by ultraviolet radiation, and despite the addition of UV inhibitors, it does decay rather rapidly. As a general rule of thumb, 100 hours of sunlight will reduce the strength of nylon by 20 to 25 percent. The thinner the material, the greater the rate of decay. This might be something to think about for fans of hanging tippet spools from a lanyard or those who store their uncased rods in a drift boat. It also should make you reconsider buying tippet spools that are displayed under fluorescent, UV-emitting lights.

So if you want your monofilament to last a long time, fluorocarbon is a good thing. If you misplace a tippet spool during lunch break, fluorocarbon is a bad thing. For all intents and purposes, fluorocarbon lasts forever, and if George Washington had dropped a spool of fluorocarbon tippet material back in the day, it would be fully capable even now of strangling and maiming small animals.

Another claim that is that fluorocarbon sinks faster than nylon. Although this is certainly true, in typical trout-fishing situations, surface tension will generally buoy tippets of 3X and smaller. Much more important than the density of the leader, if you want to sink typical trout flies, is the diameter of the monofilament and the size, shape, and weight of the fly.

Despite marketing claims, fluorocarbon is neither invisible nor even “nearly” invisible. You can Google “mathematical theory of fishing line visibility” and see the proof as described by a mathematician in seven pages of formulas. In terms of monofilament visibility, the angle of refraction is so slight as to be meaningless outside of an ad agency’s office. I’ve spent countless hours in a multitude of aquatic environments observing both nylon and fluorocarbon and couldn’t even hazard a guess as to which one was drifting by. I can see 7X tippet from five feet away, and so can the fish.

Bruce Richards, who until his recent retirement ran 3M / Scientific Anglers, a major distributor of fluorocarbon monofilament, and who has contributed more to the development of fly lines and leaders than anyone in history, candidly states: “The whole visibility thing is bunk. It is extremely unfortunate that fluorocarbon was, and in some cases still is, being hyped as being nearly invisible underwater. Of course it isn’t. If you hold an aquarium of water with fluorocarbon in it and turn it around and around in various lights, you will see incredibly small, and I mean inconsequentially small, sections of line that lose their glow. The angle of the light has to be precisely targeted in an extremely narrow plane, and that simply doesn’t happen in the real world.”This is from the guy who sold it.

Folks have made the claim that fluorocarbon is harder than nylon, and therefore it is more abrasion resistant. On the Rockwell Hardness Scale, fluorocarbon rates 100. Nylons, depending on how they are formulated, can rate as soft as 88 or as hard as 114. Nylons absorb water, which does soften them. However, most quality leaders are designed, with great effort, to be highly water resistant. Fluorocarbon monofilaments may seem harder, because many are stiffer (less supple) than comparable nylons. Counterintuitively, stiffness does not necessarily translate into hardness.

Fluorocarbon also has a reputation for being stronger than nylon. This simply isn’t true. Fluorocarbon and nylon share very similar strength-to-diameter ratios. At the high end of the spectrum, the strongest nylon monofilaments have greater tensile and knot strength than any fluorocarbon on the market. Stroft GTM nylon tippet crushed its closest fluorocarbon competitor (Seaguar Grand Max) in a static line-pull test in Fly Fisherman’s 2012 tippet shootout, as it also did under the controlled conditions of Germany’s TUV Munich, Europe’s version of our Underwriters Laboratories.

At this time, nylon also has greater knot strength than fluorocarbon. Even wet nylon that has lost some of it strength still knots stronger than fluorocarbon. In the past few years, though, fluorocarbon monofilaments have been evolving, with greater and greater knot strength, often by extruding a hard core with a soft, “chewy” surface. My hunch is that in the near future, fluorocarbon technology will produce monofilaments that will meet or perhaps exceed the knot strength of nylon.

Deepwater chironomid anglers and pros in the bass circuit have universally embraced fluorocarbon monofilament because it gives them a greater sense of “touch.” There doesn’t seem to be any debate. This would be a huge advantage, especially with 20 to 50 feet of line in the water. Most fluorocarbon monofilaments react differently to stretching than nylon monofilaments. Both elongate at about the same rate, but unlike monofilament, which snaps back to its original prestretch length, fluorocarbon is very inelastic and doesn’t rebound. I honestly don’t know if this related to that sense of touch, but it might make sense.

So much for the facts, statistics, and test results. I interviewed the best anglers I know to get their subjective evaluations of fluorocarbon versus monofilament out in the field. For the record, I use nylon the vast majority of the time for environmental reasons and for the simple fact that nylon is one-third the cost of fluorocarbon, and I have yet to see any benefit from using fluorocarbon. When fishing becomes really challenging, I may pull out all the stops and tie on some fluorocarbon to see if it might give me the edge. It never has, but I still carry a few spools as silver bullets.

J. P. Basile. J. P. guides the Missouri River for Head Hunters. He’s also my son-in-law. “I fish with fluorocarbon. I think it is stronger and has greater abrasion resistance. Most importantly, it gives me confidence. I trust it and know its limitations. Most clients believe, rightly or not, that fluorocarbon must be better because it costs so much more than nylon. My job is customer satisfaction, and if they want fluorocarbon, that’s what they get!”

Lisa Cutter. She is probably not an appropriate interview, because she’s my wife, but she is also one of the best anglers I know and has decades of experience fishing, guiding, and teaching our sport. “I use nylon. Period. None of us intends to litter, but losing line is inevitable, regardless of how careful we are. I don’t need to catch fish so badly that I’m willing to use a product that will be around for centuries. I have spent enough time rescuing everything from geese to turtles that have been tangled up in ordinary nylon monofilament.”

John Juracek. John is past co-owner of Blue Ribbon Flies and fishes Yellowstone waters nearly on a daily basis. “I only use nylon. If I still owned the shop, we wouldn’t carry fluorocarbon. I think it is hypocritical for anglers who defend the fishing resource against outside interests to use fluorocarbon, which clearly impacts the ecosystem even well beyond the fishery. Even if it caught more fish (and I don’t believe it does), it wouldn’t be worth the trade-off.”

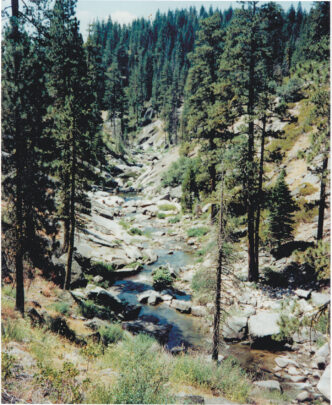

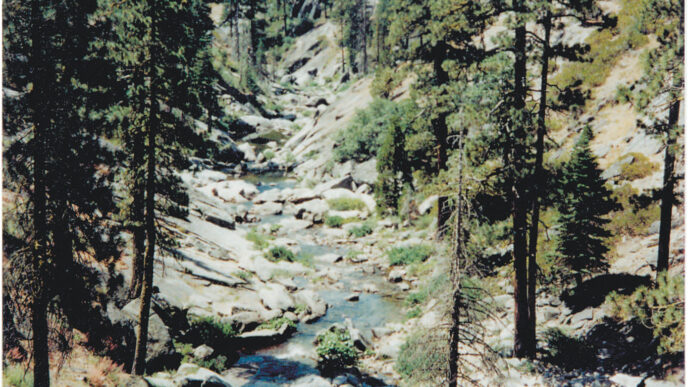

Dan LaCount. Dan is a Truckee River guide who is equally versed in fishing bugs and streamers. “I use RIO Powerflex [nylon]. It is cheap, reliable, and gets the job done. I don’t want to contribute to the potential environmental consequences of fluorocarbon.”

Craig Mathews. Craig owns Blue Ribbon Flies, and along with Yvon Chouinard, he started 1% for the Planet, a powerful environmental advocacy organization. He lives on the Madison River and fishes it at least 150 days a year. “I use fluorocarbon. I don’t hook any more fish and don’t buy into the invisibility hoax, but I lose fewer fish. Yesterday, I caught about 20 fish on the river, and today, I’m using the same piece of 6.5X tippet. Over time, I’m convinced it is better for the environment to lose a fractional amount of fluoro than it is to lose considerably more nylon.”

Brant Oswald. Brant guides on the spring creeks of Paradise Valley, Montana. He is widely recognized as one of the best technical trout fly fishers in the world. To get a date on his guide calendar might take years. “I use both nylon and fluorocarbon. For fishing on top — especially with downstream presentations — the reflectivity and visibility of the material are irrelevant. The fluoro I use is stiffer than nylon, so it might be more accurate in windy conditions, but in most dry-fly situations, the stiffness is a negative. For tandem rigs or going underwater in shallow spring creeks where you don’t want to use weighted nymphs, I use fluorocarbon, because it is denser and penetrates the surface film a little more quickly. It also seems to saw through weeds better when fishing lakes.”

Bruce Richards. Bruce recently retired as product development guru at 3M / Scientific Anglers. If you fly fish, Bruce has directly or indirectly influenced the stuff you’ve used between your reel and the fly. “Cost isn’t an issue, since I get product for free, but still, I mostly use nylon. In most situations, it is simply the better material. I want my leader to float and point to the fly, especially when the fly sinks. The closer I can see the leader to my fly, the faster I can react to a grab. As I said, this whole visibility thing is bunk. Fish don’t care. If they did, why would they eat a fly with a hook hanging out its rear end? Fluorocarbon fishing line has been around since the 1970s. If it were so great, why would we be still debating its merits?”

Phil Takatsuno. Phil has fished over 250 days a year, every year, since I’ve known him, which is well into three decades. He is likely one of the best lake fishermen alive and not any slouch when it comes to fishing freestone waters. Despite his comments, he is not in any way affiliated with Trout Hunter. “I tried lots of fluorocarbon and didn’t like it. The knot strength sucked, so I went back to nylon.

Then Trout Hunter came out with their fluorocarbon, and René [René Harrop, owner of Trout Hunter] told me to use a Triple Surgeon’s Knot to splice my leaders. The results have been unbelievable. I hook the same number of fish as I ever have, but I simply do not break them off anymore.”

Rusty Vorous. Years ago, Rusty was voted Guide of the Year by Fly Rod & Reel magazine. He is one of the most thoughtful and well-versed anglers I’ve ever met. He is an icon of the sport. “I use nylon. I don’t see the need for fluorocarbon. I catch all the fish I need to catch with nylon. I think most people who use fluorocarbon, especially newer anglers, are grasping at straws. They are looking for the quick fix, and the marketing hype has caught them in its net. The stuff lasts forever, and I don’t want that to be my legacy.”

Mikey Wier. Mikey needs no introduction. He has produced three films that chronicle fly fishing around the world and has caught some of the largest trout seen in California over the past several decades. “I have used fluorocarbon, but never experienced any advantage from it. It doesn’t biodegrade, so I have a hard time rationalizing using it. In small sizes, I want suppleness, and nylon rules. In bigger sizes, why would you use anything other than Maxima?”