Not everything has a price, I happen to believe, although it’s surprising what does and doesn’t. When it comes to old fly-fishing tackle, usually somebody’s dad’s or granddad’s, a fair number of the nonfisher acquaintances who approach me — say two or three a year — are looking to get an estimate of dollar value. When this is the case, I demur, honestly insisting that I don’t know enough to help while offering a name or two of people who, honestly, can. It’s an experience familiar to many fly fishers, I know, who also end up getting ganders at assorted Montague, South Bend, and Ocean City items. Only once was I astonished by a find, one of a special edition of three rods built by one of the most famous artisans I’ve read about. The other two were gifts specially ordered for Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill.

Not for sale, that piece. Neither were others I’ve seen, however modest, shown not for valuation, but from an eagerness to share a relative’s prized possession with somebody who might appreciate it. “I’ve never fly fished, but my grandfather was a great old guy and really wanted me to have this.” And then come invitations prompted by motives I can’t quite make out, possibly because the heir and new owner isn’t sure either.

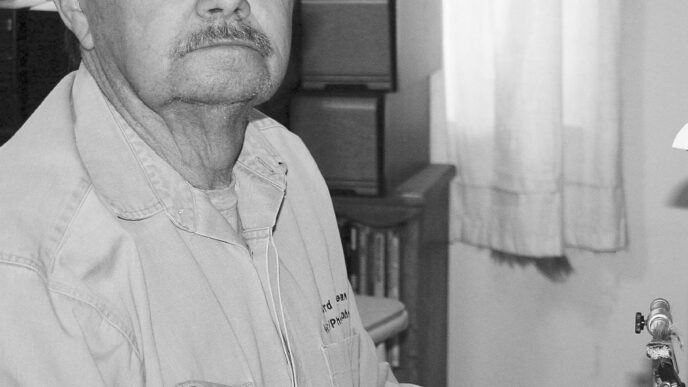

That seemed the case last summer when an older fellow I enjoy at social occasions took me by the arm. Originally English, Edward has wit and charm and grace. He’s succeeded in several fields, including magazine writing. We have that in common; also, he’s of an age and temperament that allows him to combine the camaraderie of a near contemporary with a comfortable, faintly paternal element. He even looks like my father.

“Come with me,” he said conspiratorially, when the family arrived to visit him and his lady friend. “Got something you’ll want to see.”

True. Especially the Atlantic salmon flies. As to the set of Hardy reels and fiberglass rods that his late father had left him, I wasn’t at all sure what to report. “I know they’re worth something,” he said. “And I suppose I could use the money, couldn’t we all. But then there’s the fact that I’ll never use them, and I feel quite badly about the waste.”

That I understand. But I still wasn’t the right guy to ask, so I suggested he talk to Jim Adams of Adams Angling, because I know Jim and trust him and because Hardys are a specialty of his. “Yes, well . . . I’d rather deal directly with somebody I know, if you know what I mean. So perhaps you can just keep them in mind.”

I promised I would.

And did: Edward had kept this equipment for decades. There’s clearly some attachment beyond whatever dollar amount they might represent. They belonged to his father, to whom they had a significance he didn’t share, presumably because fishing was never something they did together — remnants of a father’s life that his son never enjoyed or perhaps never understood. In his situation, would I feel — what? Guilt?

Let’s advance a few months into early autumn, to a scene superficially similar, which will instead bring us back to heirlooms kept and shared purely for reasons of the heart.

“You know,” said my hostess, amid the swirl of a families-included high school pre-homecoming-night dinner and photo shoot. “There are some things I’ve unpacked to show you, if you wouldn’t mind.”

We don’t know the couple well, but their daughter Kate is my Sophie’s “BFF,” which translates to “Best Friend Forever.” That means the parents meet at special events like this one, occasionally at Kate’s folks extremely large home on the lake. They’re very nice people, I’m quite sure, but I do find the family a little confusing.

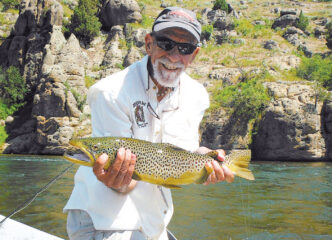

Kate is friendly, loyal, affectionate, and unspoiled — a 4.0 student who is a year younger than the crowd of teens with whom she travels, and she acts a year younger than her age. Call her a true naïf: Kate recently told her pals that she doesn’t understand why they make such a fuss about her folk’s biggest boat, a motor yacht “barely” over a hundred feet long. And before you think that’s just some rich kid’s ruse, Kate truly loves the job she’s been working most of her senior year in high school, scrubbing pots at a small restaurant. As for Kate’s father, Roger, he retired young, on what I’m told is a combination of family money and the profits of his own successful career. I’m not sure what he does now besides golf and travel, but we’ve never found fertile grounds for conversation. The same has held true for his wife, Gloria, tonight my hostess, who also retired at early middle age from a high-powered position in an HMO. Until this moment, I’d never seen her without a pleasant, if slightly vague smile on her face. “They have to do with fly fishing, and my father,” she explains.

When I answer, “Of course, I’d be glad too,” that vague smile opens up.

A few minutes later Gloria leads me to her in-home office, an unostentatious room clearly set up for work. Two metal rod tubes lean against a desk. “These were his,” she says, handing me one. “Not just his,” she says quickly, “I watched him make them when I was a small girl. I…just loved to watch him work. So many hours, so careful. The tools and the light. He was an engineer for Boeing, but also a craftsman.”

You know how some of those old tubes have brass caps with many fine threads? Caps that take enough time to twist off that you feel like you’re opening something important?

This was one of those.

Gloria watched me carefully slip the rod from a gray flannel sleeve, then as I examined the handle, heavily used, but not abused, dark thread wraps on darker cane; I checked the ferrules to be sure I could risk piecing the pair together. “You see,” she said, “how he put his initials there on the wood. Only those and the date he finished. That’s all.” So what does that say about the man, I wondered, almost certain that the modesty meant something to her.

Now let me make it plain again, as I did to Gloria, that I’m nowhere close to even an amateur assessor. While I own a few bamboo rods, I know little about them beyond what a pair of mine “say” to my hand. Though I have pored over books describing split-cane construction, read more than a few paeans to tapers, varnishes, and tempering processes, and had a friend demonstrate planing strips of bamboo . . . when it comes to knowing, I figure I understand roughly as much as a 1965 Sex

Ed lecture taught me about life’s most intimate act. (For those not of that era, photos of mayflies mating would have been far and away too graphic.)

That said. . . .

Without a reel and line — without room to flex the shaft quite as much as I wanted — this rod still seemed to me serious work, carefully calculated, cut, and joined. Nothing fancy about the wraps, just smooth and neat; a full Wells grip, stained and in some places shiny where the meaty parts of a palm and fingers gripped. Maybe a 7-weight, more likely a light 8, with a bend that it is not parabolic, but faster — surprisingly so.

“He fished salmon and steelhead,” I say.

“Oh yes. Especially steelhead,” replies Gloria, obviously pleased. “He thought they were magnificent. He . . . well, he tried to teach my brothers, but —” she shrugs — “when he died, I was the only one who wanted these. Because I’d watched him make them. The reels and the rest, I don’t know what happened.”

She watched, I note. The brothers got to try.

I look toward the other case. “I’m guessing he also fished trout.”

“Oh yes. In the streams around here.

Other places, too — all over, really.”

If the big rod had gravitas — seemed to me solid and almost stern — the second was another animal entirely. Lighter, of course, and lithe, soft, but not really slow. Warhorse and filly, I found myself thinking. “This rod is lovely,” I said softly.

“Really? Is it really?”

“Yeah. Oh yes. To me, anyway. And to him, I’m sure. I bet he loved fishing this rod.” “He did. I know he did. He always said it was his favorite.”

Suddenly I could almost feel the warmth rising from her flushed face, a pride a pleasure, then a rush of sentiment that filled her eyes.

“If you’ll excuse me a few minutes,” she said. “I need to check the oven, I think other guests have arrived. ”

I wasn’t going anywhere. I was communing with the grass, taking my time, wondering how it might throw a 5-weight line. Not hard to imagine it bowing to a rainbow or cutthroat, tension thrumming, shaft speaking to its own maker, this man in every other way forever a stranger to me.

Gloria was pleased to find me still holding it when she returned. It didn’t even occur to me that that she might want to know what it was worth, because another idea had struck me.

“You know, you could fish this rod tomorrow,” I said.

“Really? Do you think so?”

“Oh yes. Lend you a reel or two, to find the right line to load it. You could practice from your dock.”

“Oh, that’s so good to hear. So it’s still really a fishing rod?”

“Absolutely.” Then, though I found myself hesitant, I foolishly pressed on. “Look, I’m hardly an elegant caster. But I’d be glad to give you a quick lesson.” To that I added, a little too quickly, “And maybe Roger would want to try.”

“Roger?” She smiled, a little vaguely again. “Maybe. But I’ve always hoped, I still hope, that someday my sons would want to learn.”

“That would be fine, too. But why not you?” After all, you’re one who loves these rods and what they mean.

“Me?”

She really did look surprised, confused by what seemed so obvious to me. Her expression looked shy might be the

word. More than tentative, that’s for sure. And just for the record — that HMO? Story goes that she rose from the ranks of office help to become the executive who turned the entire ailing company around.

Doesn’t matter. I’d overstepped and instantly remembered that I really didn’t know her at all, a fact iterated by another smile, this one impossible to read.

“I was really thinking of my sons,” she said softly. Then, with genuine feeling, “Thank you so much for looking at these.”

Not long after that my son Max wandered into my office while I was busy. “Do you,” he began, already fussing in my desk detritus, “have something of Granddad’s around? Your Dad, I mean?”

Not a rod, that’s for sure. The only one my father ever owned was a solid fiberglass pole I’d bought him with lawnmowing money when I was ten or eleven so he’d have something to use when he took me fishing.

“What kind of thing, and why?” I asked, though I wasn’t surprised: Max has always been curious about the ancestor he’s never met.

“Oh, I don’t know.”

What or why? I wondered. Not that it mattered. “ Well there’s those,” I said, pointing at the headphones my father brought home from his last B-17. They hang from the top of a small, boat-shaped bookcase where a half dozen curious and mystical objects crowd four short shelves. The headphones lord over the rest as a war trophy, but because I watched my father wear them throughout my boyhood, talking on his ham radio in a pool of light, late into the nights of our shared insomnia. “But you’ve seen those. Also the medals, though they’re locked up.”

“Right. I was just wondering about something else.”

I reached past a file on my desk. An electrician’s knife, my father called it, a sturdy, if homely piece of work. “This was his.”

“Can I hold it?” “Sure. Then there’s — I opened the drawer beneath the printer, drawing out a bolo tie with a turquoise slide.

“Did he really wear that?”

“Instead of a tie. Here’s another one.” “Oh yeah,” Max says, obviously amused. “That’s right, he was a college professor,” he adds, in tone that suggests this explains all.

“In Arizona,” I add sharply. “There’s also a row of the books he wrote, over there on the shelf below his photo. And below those, there’s also one of the photos he took. And that little etching over there? As a kid, I thought those were my father’s hands, holding that little girl’s face.”

I stop. Suddenly it seems to me, surely to both of us, that I am surrounded by objects my father touched. I notice Max is staring at me with a quizzical expression.

“What is it,” I say again, “that you think you’re looking for?”

“I don’t know,” he repeated, but a sudden ear-to-ear grin suggests he found it.

And what will he want of mine? I wondered as I heard him tromp down the stairs. Besides a couple of guns, gifts to me that, in addition to the standard boy’s allure also come with stories. Not fishing gear, so . . . ?

Stories? Books and articles he’ll read someday, wherein he’ll find his name.

I’m not convinced. Not at all.

Suddenly I realize that I’ll never know. That perhaps I’d be surprised.

I certainly got a surprise last week, from my older English-born friend, this one at an office Christmas party.

“About all that gear,” he said, taking me by the arm. “I’ve been thinking about it. The waste, you know. For some reason, it’s actually begun to bother me. And quite a lot, really.”

“Edward. Listen. Whenever you like, I’ll give you that phone number. If you’d prefer, just make me a list, and I’ll call Jim myself.”

“Yes, well, that’s all fine. But what I’d really like to do, is bring them over sometime soon, put everything in your hands. If they sell someday, fine — don’t really care if it takes years. If they don’t ever sell, that’s fine, too, believe me.”

I look at him closely. He face is set; he’s clearly made a decision. I’m suddenly reminded of one of my own stories, where I tried to describe a process that might be like what’s going on in his mind, this crazy notion that sometimes things fall into your possession only to make their way to somebody else to whom they will matter.

Kind of a Christmasy thought, this seems to me later, which prompts me again to worry and wonder what I should really stuff into a couple of stockings. And sometime after that, Edward’s offer leads me, inexplicably at first, to remember Gloria’s smile — the odd one I couldn’t interpret, after I’d urged her to learn to cast.

“I watched him make them . . . just loved to watch him work. So many hours, so careful. The tools and the light.”

W7UXX was my father’s old ham radio call. I wrote a “Meander” with that title, some years back. And that one, I think, Max will someday enjoy reading.