In the last issue, I confessed that I wasn’t sure how to advise would-be fly fishers who wondered how best to get started, given the options available today. “While I enjoyed my own mostly solo evolution,” I wrote, “for decades, it progressed at the speed of campaign finance reform.”

But things must be different now, I insisted, thanks to a plethora of how-to flyfishing books, magazines, and flashier media, also the Internet, and a relative abundance of classes, seminars, and clubs with instructional programs. Surely, newbies should be able to learn more, faster, than solo meanderers of my era, so I speculated that those who’d recently started would be a fine bunch of folks to ask.

“I’m especially curious about relative blank slates who’ve had the options available in the last decade or two,” I wrote, “people who got the urge and . . . stumbled across systems satisfying enough that fly fishing is a large enough part of their lives that they read a magazine like this one.” With that in mind, I proposed a survey, anticipating answers that would inform and guide others. I even supplied a list of possibilities on which respondents might comment.

Of course, my motives were pure as driven snow, or of snow undriven upon; it seemed to me like a well-laid plan. If anybody had asked, I’d have insisted I’d laid far worse.

Somebody did, sort of. A writerly pal harrumphed at my proposal, a reaction that even over the phone recalled a brown trout spitting out a Marlboro butt. “Of course” we all want and need to learn more, more quickly — and “yada yada,” like that. On the other hand, like me, he’d learned lots on his own adventures, “and frankly, I’m not sure I’d have had it any other way,” he said. To summarize a longer long-distance sermon: discovering fly fishing, he argued, is itself a noble endeavor — exciting, engaging, and a whole of fun.

“Oh yeah, well,” I riposted several times, adding mumbles less than assertive because at a gut level, I agree. But at last I reminded him that we were kids way back then, with sure feet and strong backs, endless energy, time on our hands, and no idea of how much there is to know. “That’s not true for everybody starting out,” said I, piously, and there’s always been a reason for how-tos, right?

And so how did this survey invitation work out?

Badly, I believe my pal was pleased to hear — certainly so, if we’re talking about a result addressing the survey’s intent. If I have laid less successful plans, I’ve mislaid the evidence and hope it will never be found. Fortunately, that’s not the end of a story that turned out well, however differently from the one I’d originally imagined I’d write.

The overwhelming number of first responses — their content, not the actual number, which ultimately failed to compete with ESL spam — barely nodded to the possibilities I had suggested. It almost seemed as if the authors ignored these to avoid confronting me with an embarrassing gaffe. And while no writer actually said so, that odd impression was amplified by what they did include, in midlength to long essays filled with more words than this column can contain.

“Personal,” is too obvious a description for unique histories and philosophies, studded with insights and humor. They were all that, but themes emerged and resonated. Among these: It’s not how quickly you learn, or how much, or even how well. What’s important is. . . .

There’s no reason to transmute their words into mine, so I present them with permission, of course, and caveats:

It’s doubtful that any of these writers imagined I’d excerpt so much of their work, then follow up with questions and insert their responses, as well. I did edit for space and organization and excised a few typos and spelling sins writers commit when they don’t anticipate ten thousand readers will see their prose naked. I pray I’ve not altered any meaning and apologize in advance if I did.

Most of all, I’d like to say thanks.

Born in Arizona, Jack Ingram grew up in a family of “meat fishermen and women” and “began fishing for bass and bluegills and catfish while camped on the shores of Lake Havasu. This would be around 1958.” Longer trips followed, day excursions out of Newport and San Diego “fly-lining anchovies for bonito, barracuda, and yellowtail.”

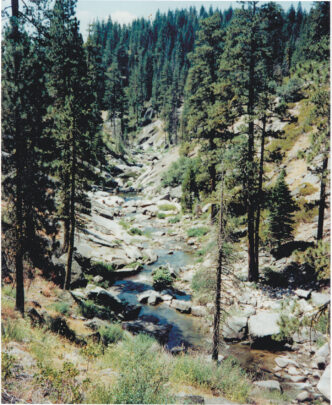

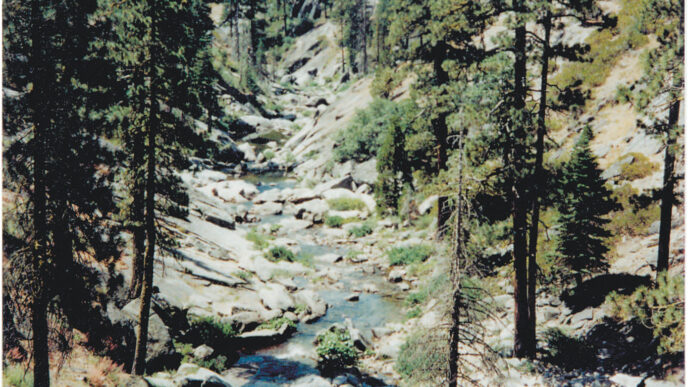

There’s a start. But “growing up under my Dad’s tutelage, I never did any stream fishing,” he wrote. That changed when Ingram “got older and acquired my own vehicle,” the better “to venture up into the eastern Sierras . . . where I would bait fish for trout with red worms and crickets.

“My high school buddy was a decent stream fisherman, and I watched him and learned. However, during my trips to the Sierras, I would encounter a few older, intelligent-looking chaps fly fishing. For whatever reason, I became intrigued by the eloquence of their sport (emphasis added).

“This was around 1975,” when there was “not much fly-fishing information [available] to a young man in the Inland Empire. I was all self-taught. No one I knew fly fished. There were no videos and not many books I was aware of at that time. No Internet.” Even so, “I picked up a few how-to fly-fish magazines in the local grocery store and began what has been for me an endless pursuit of fly fishing.”

While a lack of information didn’t stop Ingram, there were other barriers to breach. Cost, for one: “Somehow, I got a hold of an Orvis catalog. Wow. I could not believe the prices of the equipment.” Ingram settled instead for a 9-foot fiberglass Daiwa rod and Pflueger Medalist reel he bought at the local Big 5. “Somehow, I got a fly line and a tapered leader . . . purchased some flies (fly tying was still a ways off ), and headed up to the San Gabriel River and her tributaries. I fished the Angeles and the San Bernardinos exclusively, as I could not afford to travel” while raising a family “on $6.89 an hour job. (Though that was not a bad wage in 1978.)

“Needless to say, my learning curve was slow and arduous. It was a long, frustrating apprenticeship. However, I loved it from the start. My only goal was to be able to cast a line as gracefully as the men I had observed while on the streams in the Sierra I practiced casting in the local park on the grass. Ten o’clock to two o’clock was my mantra for years. I suppose subconsciously I still cast within these strict parameters. I am sure my casting sucks.”

Maybe so, but “I have seen many would-be fly fishers come and go. I feel the truly passionate fly fishers are like good artists; they are born with the passion and the gift. You have got to love the idea, the experience, the essence of fly fishing to make a life-long passion of it. It is not something watched on YouTube or read in a book. It is not a concept which you can acquire at a fly-fishing club meeting.” But “truly committed, absorbed, all-consumed fly fishers seek out their place.”

He asks, “Is it like a religion?”

“The only way to attempt to master this passion,” he concludes, “is to spend time on the water. Trial and error. Or shell out $450 bucks to a guide somewhere and have your picture taken with a sweet 20-inch fish.”

I got back to Jack, to report my pleasure in the lines about “intelligent-looking chaps fly fishing” who intrigued him with “the eloquence of their sport.” But I also ruminated over his last paragraphs. Some of my questions were large: What ignites that passion, fuels it? Others were small, because I’m nothing if not dogged: What (see the survey) might make a passion’s pursuit less frustrating (if that is important). From there, I faded into the ether. I decided to treat “Is fly fishing a religion?” as a rhetorical question that I, too, would not try to answer. But art? Not necessarily the arts obvious in exquisite flies and flamed bamboo rods, but something deeper: a refinement of predatory instincts expanding from the brainstem that, influenced by appreciation or awe, transforms an instinct to catch and kill into —

Elegance?

When I started thinking about cave paintings, animal clans, hunting gods, and saints of fishers, I knew it was time to sober up. It helped to remember a five-times-removed version of a Russell Chatham remark relayed to me last month, a report asserting that when inducted into the Northern California Council of the Federation of Fly Fishers Hall of Fame, the author and artist quipped — brilliantly? ironically? — something like, “Who knew there was such an honor for a leisure-time activity?” I also recalled and reread Richard Alden Bean’s observation in Bud Bynack’s interview of him in the April 2013 issue: “Fly fishing is at best a hobby. It’s one of the things we do to have fun.”

Of course, thought I. And yet . . . I wondered what Jack Ingram would say about that, or what I might, when I wasn’t covering my ass.

Robin Ladd was “also one of those solo initiates,” who, “after returning home from Viet Nam in ’69, bought my first fly rod and half a dozen flies, a Martin fly reel, plus fly line and leader.” He “had zero knowledge of fly fishing, but knew something about fishing in general, having spent much time during my formative years sorta fishing the Delta in Central California.”

À la Bean, fly fishing was only one of the things Ladd did for kicks. “I was only 22 years old, and it wasn’t the only interest in my young life.” “Besides college and girls,” he learned to rock climb and sail, “but my most serious pursuits were backpacking and whitewater kayaking . . . eventually becoming a licensed boatman on the Stan, the “T,” and the Kings River. But fly fishing was always something that seemed to tag along,” despite “a learning curve [that] was real shallow.”

“What I really enjoyed about the ‘sport’ was its solitude,” he writes, a matter of choice then and now. In time, the other outdoor activities “simply faded away, except for the backpacking,” and “At 66 years young, I still don the pack . . . now to seek out those even more out-of-the-way places. For me, fly fishing and solitude just go together. As far as the learning It is still slow, but I read, ask questions of more learned folks, and ‘practice,’ ‘practice,’ ‘practice.’”

Then comes what was to me a “Say what?” moment that Ladd inserted so quickly that I’ve added emphasis.“At this point in time, I guess I have become a bona fide fanatic. I make and use my own split-cane rods for no other reason than I like the way they look and feel. In fact, I wish I still had my first Fenwick glass rod, but alas, a few years ago, I fell and it broke.” But “I am not a snob when it comes to fishing,” Ladd notes.Solitude aside, Ladd ended his first message with: “Just treat the places you use with respect, as well as the people, and as my new friend Joe P. in Penn. says, ‘do good and disappear.’”

That was an excellent sign-off, but not quite enough. It’s one thing to tie flies, another to build rods, something else altogether to plane these from grass, so when Ladd added “Go Raise Some Cane,” my first thought was “Wait — he’s not growing the stuff, too?”

Not quite. But close, Ladd acknowledged in a reply to my e-mail responding to his: he’s teaching rod building to a younger friend, helping him to avoid “my many mistakes.”

That friend “became interested because he wanted to. I simply helped him along. He just finished his second rod, a 6’ 9” 4wt. Garrison taper. Mentoring is the key. The challenge is finding a compatible connection.”

That’s also for true for groups.“I tried for a year and a half to ‘fit in’ with a local fly-fishing club, and you would think that would be easy, because of like-mindedness. But to no avail. Instead I have become involved with a national organization (Project Healing Waters Fly Fishing). Go figure? But my connection with them is that I am a Viet Nam vet.

“My point is, when I push for something, things don’t always work out but

if I simply let my passion guide my course of action” — or here, renew and redirect it — “more often than not, things work out.

What I’m trying to say is that if the passion is there, anyone can get it done.”

The passion. The gift.

To Vaughn Willett, it’s motivation that’s critical, not just from learners, but from those who decide to teach them:

“When it comes to helping someone get started fly fishing, there are a couple of key questions you/we may want to pose early in the ongoing dialogue that is the teaching process:

- What are your motivations for taking up this sport (or teaching it)?

- What are you trying to accomplish in this sport (by teaching it)?

“It may not be possible to ask these questions of your student directly, for any number of reasons, but the answers are important. The ‘what’ and ‘why’ are just as important as ‘how’ — for both the teacher and the student.”

I responded. When Willet got back to me, he made it clear that he’s speaking from real-time, present experience. Like Ladd, he’s teaching — fly-fishing skills to an old friend who’s brand new to the sport. But Ladd didn’t begin without a little trepidation: “When he and I started this process, I was constantly gauging his level of interest,” prepared, if necessary, to disengage the new role of instructor from a significant and long-standing relationship.

Not to worry. “He has proved to be a committed fisherman, though still a novice, and it’s a lot of fun fishing with him — which is one of my motivations for continuing.”

It does sound like Willet’s old friend and student now shares Willet’s fascination: “To my mind, fishing raises more questions than it answers, which is one of the reasons I love it. That and the magic of getting a wild animal to eat something I have tied on a line.” If so, that raises an issue: While it may not bring us around to born to, at least it poses the questions of Who?, How?, and When?

Donald Simon seemed to come closest to the “new and learning” survey candidate to whom I’d appealed. At least, he wasn’t raised on the fly, from what I can tell from his description. Indeed, he came to the sport almost by accident. “My wife and I were on a trip to Australia and decided that since our flight connected through New Zealand, we’d take a couple of days touring the North Island. Bottom line, we stayed at a famous lodge and spent one day fishing with a guide. It was the first time I’d ever been fly fishing. Wish I knew then what I know now. “That got me started, as I realized how little I knew and how I squandered such a fabulous opportunity. I didn’t realize I had ‘caught the bug’ until I started reading John Gierach’s books. That’s all it took for me to first visualize the allure of the sport.” Simon doesn’t race into how he proceeded, but explains why, partly by providing a comparison that others may also recognize: “At the time I was an avid and decent golfer, playing a couple of rounds a week. When I started fishing, I quickly realized something that moved me closer to the passion I feel for fishing today. After a round of golf, where I might be 2-3 strokes off my average score, I was ‘unhappy’ with myself, even to the extent that I felt I had wasted my time. Alternatively, fishing a small stream, where nothing was caught except bushes and body parts, and, spending the rest of the time unraveling balls of tippet, I was happy. Regardless of the failures on the water, I always felt the time I spent was special. Comparing the two, it didn’t take long for me to put my golf clubs in the back of the garage and expand my horizons in the sport of fishing, including fly tying…

“As of today, 10 years into the sport, I’m a mediocre fisherman and don’t care. I just love the sport. Oh, as for golf, I play about 2-3 times a year and enjoy just being able to get the ball in the air.”

Of course, I couldn’t help but chase Simon for more. And he was kind enough to add the following, with enough of an implicit grin that might remind you of a brown trout seizing a Marlboro butt and lighting up.

“Regarding how I would learn the second time around and/or suggest teaching to others:

“1. I have no regrets putting in hours beating a stick against the water. When I go to heaven, there will be a lot of fish waiting to thank me for moving them away from fishable water.

“2. Teaching process for someone new — go with a guide your first time out. Somewhere in our school careers, we had a teacher who got our interest. That magical experience holds true in the sport of fly fishing.

“3. If I did have the perfect answer, I’d start my own program, but more likely keep it to myself for selfish reasons . . . after all, I am a fly fisher” (emphasis added).

Note those last few words. I did, again, when pondering, again, this survey result. How-to books and DVDs on casting, stalking, flies and fly tying; clubs, seminars, classes; Internet resources: I’ve read and heard people recommend all the above and continue to believe in their value. I humbly acknowledge that “how to learn” is not the point of most value that emerged from the survey — I don’t think I presented it well — even if parts of these stories made me want to shout “Curtis Creek Manifesto!”

But when it comes to manifestoes . . . to identifying and declaring essentials on which everything else depends . . . passion, gift, motivation, commitment . . .

For a while, I tried to find clever ways to grasp these writers’ themes in a catchy phrase. Nothing catchy, however, seemed fair or just. Fly fishing as “leisure”? Nobody who reads Russ Chatham’s Dark Waters forgets its intensity. Fishers of that place and time and writers of a certain age, including this one, found inspiration and magic on those pages, and so can everybody who’s come after (as have millions of people who’ve studied Chatham’s paintings in silence.) I do understand “fun,” as Richard Bean uses it, but while I spent time with my son this week, “fun” struck me as a funny word for certain kinds of feeling.

Max still learns to fly fish, sometimes, only to please Dad. Once in a while, I encourage this . . . like Wednesday afternoon. It’s spring; we cast on the lawn. Max looked good and enjoyed himself.

Fine. But Max’s love is cars, cars, and cars. He’s been like this since he could talk and now knows as much about his subject as any auto fanatic I know, including one awed friend who writes about cars for a living.

So. The following day, I took Max out for his first driving lesson — an empty parking lot, some stops and goes, I promised. “Brake; now accelerate, smoothly.” Just as we started, Max grinned and said, “Don’t worry, Dad, I’ve been doing this for years on video games.”

It’s not the same, I assured him. It wasn’t.

You don’t see that kind of smile, or all those smiles, unless somebody’s tapped into something special. What they were born to, maybe — passion, art, gift . . . Now, if somebody has surveyed parents for answers that will help me learn how to make sure Max survives the next year —