What I was about to do was foolish. I knew that. People already had questioned my mental stability for fishing the moving water of Keswick Reservoir from a float tube. When I visited in March and discovered that the water level had dropped a good 12 feet, exposing the only white water I had ever seen at Keswick, I was especially happy to have the fishing all to myself, as usual. It was never a question of whether or not I was going to shoot the rapids in my float tube. The question I meant to explore was something else entirely: Can you really ever go home again?

Keswick Reservoir, the nine miles of Sacramento River water that flows between Shasta and Keswick Dams, just north of Redding, had long been a kind of home to me. I had logged more years fly fishing and guiding there than maybe anyone else. While the methods I used to fish it were unorthodox enough to keep most people from trying it, float tubing the normally gentle flows was familiar to me, pleasantly comfortable, and wickedly productive. Access across Shasta Dam required only a driver’s license, and there was a campground just below.

However, Oregon was now where I lived, and at first, I thought I had good reasons for not driving down to Redding, my former home and fishing Mecca for all those years. It bothered me that I still knew more about fishing in Northern California than I did where life had taken me since then.

Spring break had finally arrived, schoolteachers’ only hope for keeping some of their marbles until summer. I knew I was going fishing somewhere. The Oregon weather forecast promised rain, rain, and rain, but the forecast for Redding pledged a sunny 70 degrees. When I learned my wife was hosting a gaggle of high-school girlfriends in our home for that week, I needed no further provocation and no instruction in how to become an itinerant fly-fishing bum. It was a lifestyle I had refined in my former life. It was California, here I come.

Ups and Downs

“Whoa,” I said in exuberance when I first saw Keswick again. It was good to be home. Then, “It looks different.”

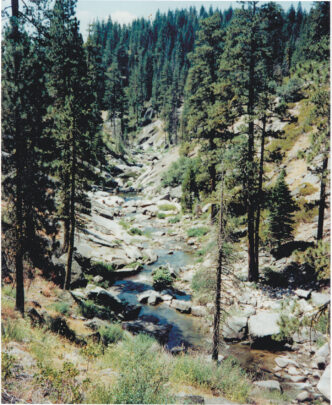

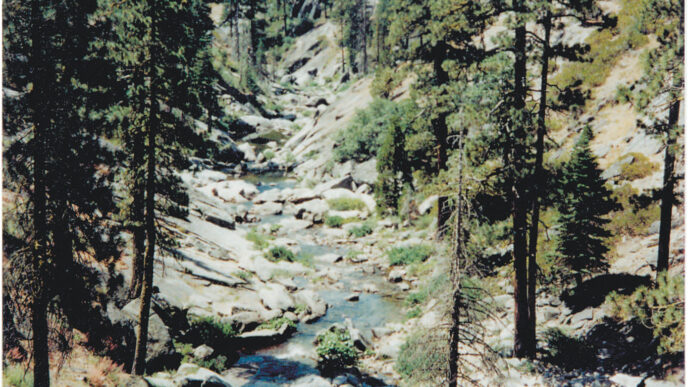

And it did, in almost the same way as when you run into an old flame years after the fact. Unless there have been drastic changes, or gravity has been particularly unkind, you tend to see the good first. You recognize why you originally were attracted. Yes, Keswick was different, but it was still gorgeous, and vacant of other anglers. I approved. Fortunately, this was a one way conversation, and no one was there to comment on the probability that I, too, looked different, gravity notwithstanding. On the day I arrived, Palm Sunday, upper Keswick Reservoir resembled a river. Where I had never seen bank access before was a wide-open, rocky area that could easily be fished from shore. When the reservoir was full, this access did not exist. I knew the water level fluctuated, but never this much. By the wet algae on the rocks, I deduced that the water level had not been that low for long.

The place where I usually launched my tube was high and dry, and it would require a slog of at least 30 feet through deep mud to reach the river. Instead, I slung it over my shoulder and hiked upstream from the campground and found another trail down to the water.

I heard it before I saw it — the unmistakable roar of rushing water. When I spied the whitewater riffle, I all but keeled over. “What the hell,” I cursed, trying to find my equilibrium in an abyss of uncertainty. Instead of the deep, bank-to-bank flow of water I was used to seeing below Shasta Dam, I was gawking at a stretch of Sacramento River few people had seen since 1950, when Keswick Dam was completed. Part of what protects the Keswick fishery is difficulty of access. Typically, there are almost no opportunities for wading, except downstream a few miles, where Motion Creek enters the reservoir. You either have to motor up miles in a boat while watching carefully for gymnasium-sized boulders just under the surface or join the nutcases like me who prefer to float down it in a portable watercraft.

Now, at least for a few days, bank access was wide open, and I was staring at a genuine riffle. Then it hit me: “I know how to fish riffles.”

The gear I always took to Keswick served me well, though some adaptation was needed. Since my routine was to fish from a tube while drifting downstream, I always brought a pair of waterproof sandals for the hike back up. Fortunately, my sandals had stretched enough to fit over my waders, and they were a lot less cumbersome than hauling my wading boots around in a float tube. I jumped in the tube, kicked across to the far side above the riffle, removed my fins, and replaced them with sandals. Since the streamside rocks were wet and covered in algae, I also had brought a collapsible wading staff, and that ended up saving my bacon more than once.

Shamu, and Then Some

It stuck me how unprecedented it was to wade a riffle on upper Keswick Reservoir. Fortunately, I didn’t catch a fish on my first cast. Any slightly superstitious angler can tell you catching a fish on your first cast is the kiss of death. When it happens, emotions soar with anticipation of the hooking frenzy that is sure to follow, only to be replaced by disappointment when it becomes obvious this was the first and last fish of the day. But when I lifted the rod on cast number two, I felt the thunk, thunk, thunk of a thick fish. Nice.

That was an understatement. The dang thing was corpulent, a football with fins, an aquatic version of those people you see who have to wear yards of clothing in order to stay covered. I tightened my drag and palmed my reel to slow it down while I stumbled on the slippery rocks downstream. It was Shamu the rainbow trout.

Though I doubt anyone reading this will ever have the opportunity to fish a riffle on Keswick, I don’t mind admitting that you fish it like most Northern California riffles: dead drift with nymphs and a strike indicator. I hooked several fish there and one that made Shamu seem small, though I could never prove it. What happens when you hook one of these huge Keswick fish is a little underwhelming at first, but when you look back on it, you get chills. “Here there be monsters.”

My indicator hesitated, and I lifted the rod on something solid. There was no give, no head shaking, no movement. Assuming it was a snag, I lifted my rod again, tug, tug, tug — tug, tug, tug from this way and that. Then the snag started moving — slowly, deliberately, like a tree limb I’d hooked that was suddenly dislodged and drifting downstream into the faster current. Lifting my rod higher for more leverage only seemed to bring awareness to whatever it was that something was trifling with it. A quick burst of speed jerked my rod tip down and I heard the sickening ping of 4X fluorocarbon breaking like thread. That was it. Though I was completely alone, there was a sense that I was standing there naked and a busload of tourists had just arrived.

Ignorance and Bliss

That is part of the mystery that surrounds Keswick. There are things I will never understand about it, and that’s OK. How big do the fish get? (My personal best is a 26-inch rainbow in the net.) Why don’t the fish take dry flies? Why are sinking lines so rarely productive? Why have I never seen a Keswick angler land a fish from a boat? Are there also brown trout in Keswick, as some old-timers claim?

All that mystery might seem daunting, were it not for a few things that we do know about Keswick. The water fluctuates up and down, seemingly all the time, which makes a float tube the perfect conveyance. Pontoon boats might work, as well, if not for the fact that there are precious few places big enough to get something that large out of the water. Whatever you float down in, you must carry or roll back up the trail at the end of the day. I wouldn’t recommend doing that with a pontoon boat.

I would recommend trying the floattube option, though. It isn’t as crazy as it sounds, just unconventional. The trickiest part is not managing the moving water in your tube, but maintaining a dead drift with your nymph while you are moving one way and the water you’re fishing is moving another. It’s tricky, yes, but not impossible. You’d be surprised how quickly you can adapt to it, and with a little practice, you will be amazed at how much your presentation skills will improve. There are plenty of places where you can shelter your tube in bays or behind rocks and not have to fight the current.

A drag-free drift is much more important at Keswick than the particular nymph you choose to fish. Keswick trout see too few nymphs to become selective about patterns, but if you fail to present your nymph well, you might be tempted to join the skeptics who doubt there is good fishing at Keswick. If you can make good nymph presentations upstream, across, and downstream, you have what it takes to succeed. The only other necessity is the ability to cast at least 30 feet from a float tube, a skill-less common than you might think. Look for slowly moving water from about three to six feet deep. If you can see bottom through polarized sunglasses, it’s probably good fishing water. If the water level rises or drops while you’re there, these areas likely will change. Because of its changeable nature, each time, fishing Keswick is a unique experience. If the water level is much different from the last time you were there, the fish may be in entirely different places. Remember the three-to-six-foot rule, and you’ll usually be in the zone where fish are most likely to feed. Fish may cruise through the faster current going down the middle of the reservoir, but don’t waste time fishing there. The fish feed along the edges.

That being the case, there’s a lot of casting in toward the bank. The shores of the reservoir on both sides are typically lined with eddies, which means that the water along the banks is often flowing upstream as you are drifting downstream, but these edges hold fish.

The farther down the reservoir you fish, the more likely you are to encounter still water. Generally speaking, you are usually better off passing by these areas and looking for slowly moving water in the three-to-six-foot zone.

I prefer a 9-foot 5-weight rod with a 9-foot leader tapered to 4X fluorocarbon. Since there is a lot of casting and I don’t like tangles, I fish a single, tungsten-beaded nymph under an indicator. Most days, I fish a beaded size 12 brown Bird’s Nest, but I believe almost any similar pattern would work just as well.

Keswick does not fish well in the dead of winter or in the blast-furnace months of the summer. The best months are April through June, then mid-October through November.

Secret Bears

Guiding from a float tube one fairly warm day, I looked downstream and saw a head moving across the water from the far side to the trail side of the reservoir. It looked like a dog, but then I realized how large that dog would have to be. In a flash, I realized it was a bear, apparently trying to cool off. My mind immediately flashed back to a Robert Traver short story, “These Tired Old Eyes . . . ” from his Trout Madness collection.

“Heeey, Mr. Bear,” I yelled as my client and I drifted closer, but still well upstream. A jolt moved through the bear’s body, and he looked right at us, absolutely thunderstruck. He executed a perfect Uturn and headed for the bank at full throttle, crashing through the trees and brush from whence he’d come. It was such an unexpected experience and so comic that it took us a few minutes to compose ourselves and get back to fishing.

Now, fishing my way downstream on those days of very low water revealed something more — a gift really — that I probably never would have seen if the lake had been at its usual height. There, under a deeply undercut bank on the trail side of the reservoir, was a small cave. In front of it was a sandy beach that would be submerged at normal water levels. There were curious markings in the sand, and I realized that whatever made them could only have come from the water. The cave was surrounded by a thick mantle of blackberry bushes on all but the waterside.

To my amazement, I saw that the markings in the sand were bear tracks, one set leading up to the cave and another back to the water. The notion that Keswick’s secret bears were still around brought a smile to my face. The old gravel road up above that used to be a railroad right-of-way was now a freshly paved hiking and biking trial full of people, with secret bears underneath.

Reflection

A phone call to the Bureau of Reclamation office at Shasta Lake after the fact assured me that the conditions I had witnessed at Keswick were only temporary. Repairs were being made to a temperature gauge downstream, and a new warning buoy was being installed on a rock noted for tearing the bottom out of boats. The reservoir level was back up again, they said, and things would return to normal a few days later. The conditions I had experienced were a fluke.

Time brings inevitable change. Keswick was different. It had been “discovered” since I’d moved away, but not necessarily by anglers. The almost endless parade of bicyclists on the beautifully paved trail next to the reservoir and the whine of countless dirt bikes in the OHV area testified to that. I still got to hike back to camp with my float tube slung over my shoulder, but it was now on actual pavement and with a lot of company. The hike was filled with repetitive chatter, “Catch any fish?” “Catch any fish?” “Catch any fish?” as each new group of cyclists passed. Some got yeses, some noes, and some a sly smile, a wink, and a tentative maybe.

The thing about reflection is, it goes both ways. Keswick was not exactly as it had been in the past, yet, I realized, neither was I. Years had passed for both of us, as they must, and they were good years. The fishing was still marvelously unusual, perplexing, and productive. Though often generous, Keswick still kept secrets, and I liked that. When I left for Oregon, I had a sense that you can go home again — and more. I caught some great fish, lost a few monsters, shot the rapids in my float tube, and posted a video of it on Facebook. I smiled overfishing Keswick at low water, however temporary that might have been. But Keswick also had smiled back at the newer version of me. I think she approved.