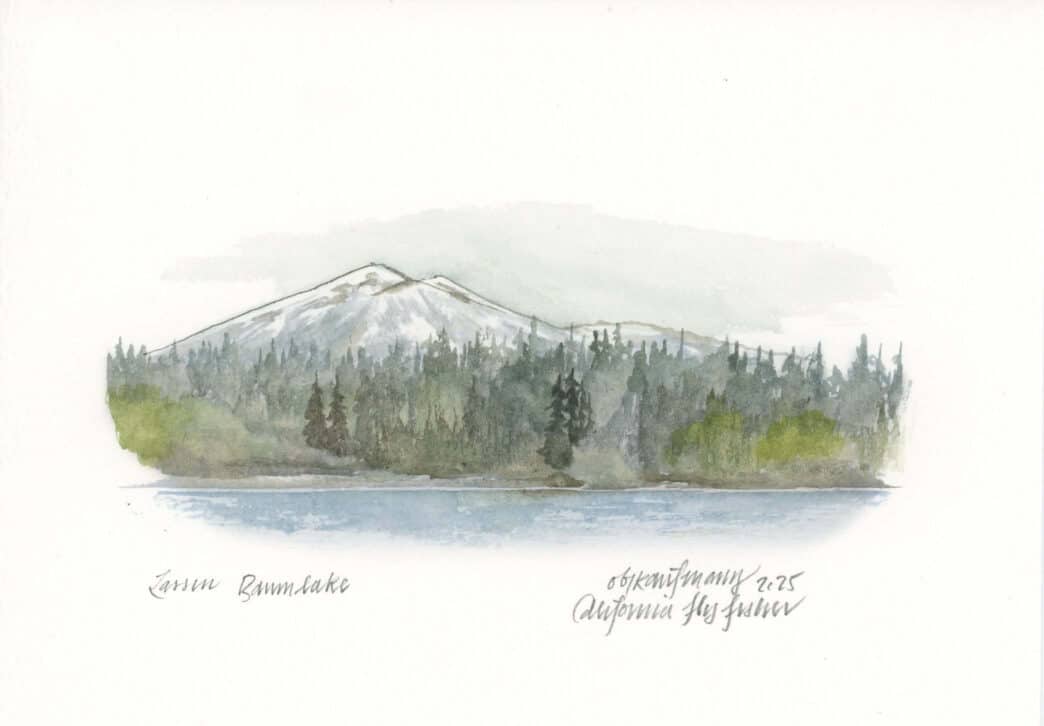

Baum Lake

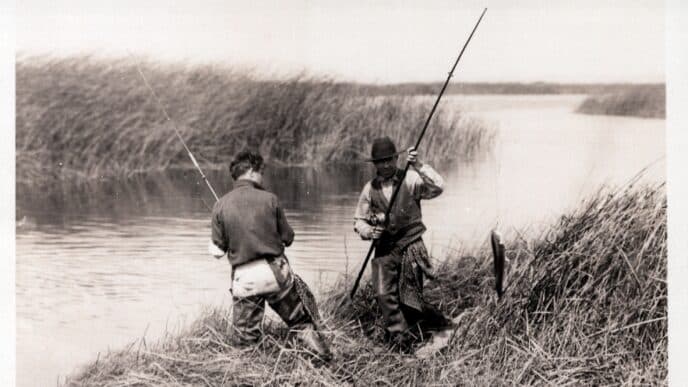

Come late spring and early fall, I get a perennial itch to float an insect on top of some ruddy water and set a barbless hook into the lip of some poor bastard of

a trout.

To balm my needless daily trifles and fiddle-faddles and instead unspool a red-letter day. More often, the trout is a somber hatchery rainbow, so happy to be in free water that a gooped up Elk Hair Caddis looks just dandy enough to fill their evening belly. And a trout’s belly can never take no for an answer.

A haunt at the local fly shop in Dunsmuir, a rod case on the top of his Tacoma, a cold Mexican beer in the dark on his tailgate, my father is an unapologetic dry flier and barbless hook-er and catch-and-releaser til he’s good and gone and his ashes swim with the browns in his adopted home waters in the high desert of Eastern Oregon (exact river name omitted because, well, you know).

Thus, I too am taken by the evening rise and the feel of cork in hand, the cool water sucking at my waders and the smooth rocks underboot. I set the de-barbed hook and utter a “got one” to myself, then consummate the trout v. biped tussle now at hand.

South of that Oregon river, one range over and across state lines, in the cool shade of Mt. Lassen, sits Baum Lake, the perfect lakelet for a stumblebum fly fisherman like myself and an aged one like my father. Once you’ve been beaten up by the persnickety McCloud or the scabrous Hat Creek, Baum provides a respite for the angler who just wants to make a few placid casts to some open water in the warmth of the afternoon sun.

My rod tightens a few lines strictly from muscle memory, despite the rust that’s built up in my shoulder and forearm all winter and early spring. Yet I read John Gierach tales all year, and chase them with Jim Harrison novels and Peter Heller mysteries. But there’s no replacing the current that flows through your arm with a trout on the end of your line.

Baum quickly doesn’t disappoint as I lay into a 15-incher not 20 minutes from launching my single-angler pontoon boat. My flippers paddle me in zigs and zags and the trout see it all from below with their eyes like eclipses, black over yellow, like moon over sun.

The narrow lake sits in a mixed conifer forest of firs and pines and oaks, where Lassen officially heralds the Cascades. Disregard the lake’s inlet near the powerhouse that gets so much of the angler attention, and set a course for open water. There’s a deep channel running through the middle (supposing six to eight feet is deep) flanked by tules on one side that holds the wiser rainbows and a few browns and even a few of mixed blood.

Now, I’m no surgeon with a fly rod, more of a deli butcher, but I manage to drop a cast or two right where I aim and float a Royal Wolff directly over the heads of the anxious-to-eat ‘bows. A pulse of current rives through my arm, a strike, not dissimilar to the hydroelectricity for which this lake was built. The trout shakes and vibrates and breaches, but my fly never wavers in his lower jaw. This won’t end well for him.

Trout were put here to enrapture our imagination and sustain the taloned and the clawed. Baum Lake was put on this spot to capture hydroelectric power from Hat Creek. Though, is not every lake and stream now rearranged by human hands in countless ways? Even the high alpine ones that took us longer to conquer?

Made by the Pacific Gas & Electric Company, Baum was flooded up and named after their powerhouse engineer many years before the company went scorched earth on untold swaths of California land. The Pacific Crest Trail meanders along the water for a stretch as well, but only one lone trekker was making her voyage. Everything across this landscape has been deflowered in some way. Countless ponderosas around the lake have succumbed to a dot of pink spray paint. They must come down later, when the weather allows, for some bureaucratic reason.

Though, at risk of angler blasphemy, it’s fair to say that when your eyes lift up from your bedraggled Parachute Adams for the slightest moment, something about the lake surpasses the trout fishing. Baum whirs to life, a bacchanal of coyote, mule deer, buffleheaded ducks, laughing coots, flocks of great blue herons and their spindly legs, aquatic garter snakes (one tried to catch its breath in my boat), beaver lodges, oak groves, bear scat, chestnut acorns beneath oaks peppered with a thousand holes drilled by acorn woodpeckers for their cache. Two largely pescatarian bald eagles circled and circled for their breakfast to no avail. A corporation made this lake, but the landscape paid it no mind.

Out there too are lions and black bears. Black bears abound, their numbers ever increasing. Cause for immense optimism. But out there now is something much more. Something so unimaginable just a scant few years ago. Something for which I want to hold my breath all night and listen for their canine call. A pack of gray wolves. Here and now in our own California.

The predators of the apex are thriving. And I am struck by the thought that a few grizzlies in Montana and Idaho could very well drift into Eastern Oregon in a couple decades and maybe, just maybe, quietly slip down into the northernmost part of California and restore Ursus arctos californicus to their forgotten homeland.

But those are considerations for another time, perhaps 50 years from now. For the rest of the afternoon, I lay down my ruminations and let the trout dictate my thoughts. For it’s the Elk Hair Caddis on the end of my line and the speckled trout eyeing it from below that unburdens the quiet of my mind.