For more than seven decades, Al Kyte has been a quiet revolutionary in the world of fly fishing. While many know him as a gifted educator and writer, Kyte’s pioneering research into the biomechanics of fly casting helped shift the way we understand, teach, and perform one of angling’s most fundamental skills. At a time when casting instruction relied largely on tradition and imitation, Kyte brought a teacher’s insight and a scientist’s precision to the task—analyzing movement, celebrating variation, and encouraging a more inclusive understanding of technique.

In this conversation, Kyte reflects on a remarkable journey that began in the Sierra streams of postwar California and led to classrooms, casting ponds, and conferences around the world. His memories are as rich as the waters he fished, filled with stories of mentors, old-timers, and innovations that transformed the sport. Through it all, Kyte’s humility, curiosity, and gratitude shine through—reminding us that the best teachers never stop learning.

What follows are highlights from an interview Dan Madison and John Krieter of Diablo Valley Fly Fishers conducted with Al in 2022.

How did you start fly fishing and how was it different then? Was there a person who helped you get started? I got my start just after World War II in the late 1940s when I was about 12 years old. There were far more fish in the streams then. It was not unusual to see small schools of fish darting around. That was partly because there had been so few people in the mountains fishing during the war.

I was fortunate to have an uncle who was a skilled fly fisherman. He was excellent at fishing freestone streams with a dry fly, and he gave me what would be the equivalent in today’s market of about $5,000 worth of fly-fishing lessons. The anglers we saw were mostly fishing with bait or spinners. The few fly fishermen were typically fishing with an attracter dry fly. We almost never saw a person fishing with a wet fly. Some years passed before I even heard the term nymph fishing.

There was a whole different fishing ethic, more of a farm work ethic. If you were going to take a break to go fishing, you were expected to at least bring home a mess of fish to feed the family. I remember my uncle talking about “dudes,” people who wore fancy fishing gear. To my knowledge there was no slogan of “catch and release” and we hadn’t heard of barbless hooks. The first conservation slogan I remember was, “Don’t kill your limit; limit your kill.”

How did you get started teaching fly fishing classes? I started teaching fly fishing through a University of California summer extension program after being asked to offer a physical education class there in summertime. So, I created a recreation class in fly fishing and it turned out to be highly successful for years.

I taught five consecutive Wednesday nights for three hours each night—the first half of that time out on the baseball field casting, and the last half inside teaching other topics such as knot tying, aquatic entomology, reading the water, wading techniques, safety, and equipment. Then we met up on the upper Sacramento River for two or three days for our field trip. I taught those classes for probably 20 years.

Meanwhile, Andy Puyans, who had a fly-fishing shop in Walnut Creek was offering a class back on the Henry’s Fork in Idaho. He was having a problem with that class in that some of his students were just not prepared for the sophisticated level of his spring creek techniques. We teamed up, agreeing that beginning anglers should take my class first and then move on to his class for a further challenge. So, for years we had this one/two punch with two very different experiences: a freestone creek experience followed up by a spring creek adventure.

It worked well and Mel Krieger got wind of it. Mel had been offering the only well-known fly-fishing school in California. He asked if I would like to help teach some of his classes. He would typically hire a few knowledgeable fly fishermen to help teach an indoor class or two during his two-day, weekend schools as well as help with the casting sessions.

Soon I became the head teacher for Mel’s classes when he was unable to attend personally. I taught all over Northern California and got to know other knowledgeable fly fishermen Mel brought in to help teach.

During those years, Mel and I benefited greatly from one another’s influence. Each of us had something the other person needed and valued. He kept picking my brains for teaching ideas because of my educational background, and I was picking his brains for casting ideas because he had been spending so much time with tournament casters.

How did you start writing about fly fishing? The first article I wrote that had to do with fly fishing was about aquatic entomology. My friend Howell Daly was head of the Entomology Department at Cal but also a member of the Golden Gate Casting Club in San Francisco. He and another faculty member, who was a caddis fly expert, Vince Resh, agreed to co-teach a class in aquatic entomology through the adult extension program.

About 20 of us fly fishermen signed up for that six-week class, which gave me a rather unique background in that important fly-fishing topic. I was soon able to key out insects under a microscope that I had found in and around aquatic habitats.

I believe my most important article was “In Search of Etiquette” in which I put together a questionnaire and got responses from 50 experienced California fly fishermen, which I wrote about. I still believe that was by far the best article written on angler etiquette. In fact, here, years later, it was recently reprinted in California Fly Fisher, because of the continued need for more courteous behavior when fishing.

The article that brought me the most recognition was the article published in Fly Fisherman magazine that reported the findings of my research on the biomechanics of distance casting. It was titled, “Going for Distance.” Soon I was hearing from readers in Norway, France, and England and even gave permission for it to be translated into Japanese and re-released in a fly-fishing magazine in Japan.

How did you become involved at the national and international levels?

I guess my writing started me in that direction. My fly-fishing instructional book, Fly Fishing—Simple to Sophisticated was pretty successful, selling more than 20,000 copies and continuing on through several editions.

Yet I think there were three other factors that intertwined to bring me more widespread attention than that. The first was my biomechanics of casting research, the second was being selected to the Federation of Fly Fisher’s initial casting board of governors (to set up and run this country’s casting instructor certification program), and the third was being selected as a freshwater advisor on the Orvis pro staff.

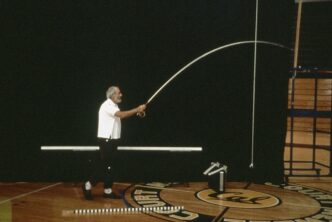

The biomechanics research occurred because of my comparing fly-casting biomechanics with other sports. I had coached and taught a lot of throwing and striking arm movements in basketball, baseball, tennis, and fly casting, and only the fly-casting movements had not already been analyzed from a biomechanics perspective.

Fly casting was an activity ripe for research of this kind. The analyses done prior to this were mostly engineering studies on the relationships of such things as flex of the fly rod, path of the rod tip, and formation of loops in the unrolling line. Virtually nothing had been done on analyzing differences in the person doing the casting—the part that teachers want to know most about. And most of the top-level fly casters were not professional teachers, so tended to be dogmatic and defensive about their own style of movement. I needed to get at what was really going on with the various casters to achieve the effective loops that the engineers were so interested in.

A visiting professor of biomechanics in our department at the University of California, Dr. Gary Moran, was very helpful in guiding the direction of my research study. He indicated that, first, I needed to decide whether I wanted to measure the accuracy or the distance of the casts. I thought about that and realized that the distance cast would require more movement by the caster, thus allowing us to get a more complete picture of differences in people’s casting styles.

We decided that the testing of 20 casters, all effective distance casters by some standard, would allow us to analyze the differences in characteristics between the most successful distance casters and other successful fly fishers who were not able to cast quite as far.

We did a detailed study on distance casting inside the Harmon gymnasium at Cal, and later a second study in which we looked at different styles of casting as well as a few other variables. The results were published in Fly Fisherman magazine as well as in an international biomechanics journal. It was widely read and well received. There had not been anything like it done before and it has remained the landmark research piece of its type.

Dr. Moran presented our study at an international biomechanics conference and told me that a number of the scientists there were fascinated with it, although not necessarily interested in fishing. They couldn’t think of another activity in which a person could maintain such prolonged control over the movement of a flexible lever. The closest thing they could think of was pole vaulting.

Are these studies where you became known for your ideas on “substance and style?” I believe the phrase “substance and style” has been used in many contexts, but I first heard it applied to fly casting by Mel Krieger.

When the fly-casting instructor certification program became a reality, one of the first things Mel did was to write a little booklet, Observations on Teaching Fly Casting. He asked a couple of us to help edit what he was writing, and one section was on “Substance and Style.” I believe I had influenced his thinking on that because I had alerted him to the fact that there are “acceptable variations” in most athletic movements. He was already critical of those fly-casting teachers who insisted that students move the same way they do and wanted to invite instructors to be open to the idea of different styles of movement.

A few years after our first research was published, Dr. Tony Stellar, the head of a sports medicine clinic down in Southern California, asked if I would do some additional research on distance fly casting. This gave me a chance to look at differences between a person’s short and long casts, between distance casting with fast and slow rods, and between distance casting with shooting-taper and weight-forward fly lines. Once again, I called on Dr. Moran for added input, and our results were first published in 2000 in American Angler under the title, “Fly Casting: Substance and Style.”

In effect, that article got many people thinking about styles of casting for the first time. And many of the findings of that study became fresh ideas and approaches for teaching fly casting that were soon fully described in my fly-casting book.

This openness to different styles is probably what will be most remembered about my teaching. I am fortunate that about 95 per cent of my best casting and teaching ideas are published in the same reference, my casting book—The Orvis Guide to Better Fly Casting. This book has become required reading for anyone preparing to be tested for Master level instructor certification.

What has this been like for you, looking back across the 75 years you have been active in fly fishing? Today, I look across time at the overall effect of fishing on our trout waters, and certain factors stand out. With far more people fishing than before, spending many more days each year on the stream and armed with far more information on techniques for catching fish on a fly, the effect has been a consistent decrease in the numbers of wild fish in most public waters. When I was young, a person could pull over at almost any good-looking trout water on any stream in the Sierra and have a good chance of catching a few fish. The last time I saw a stream such as that was in a lightly traveled part of British Columbia.

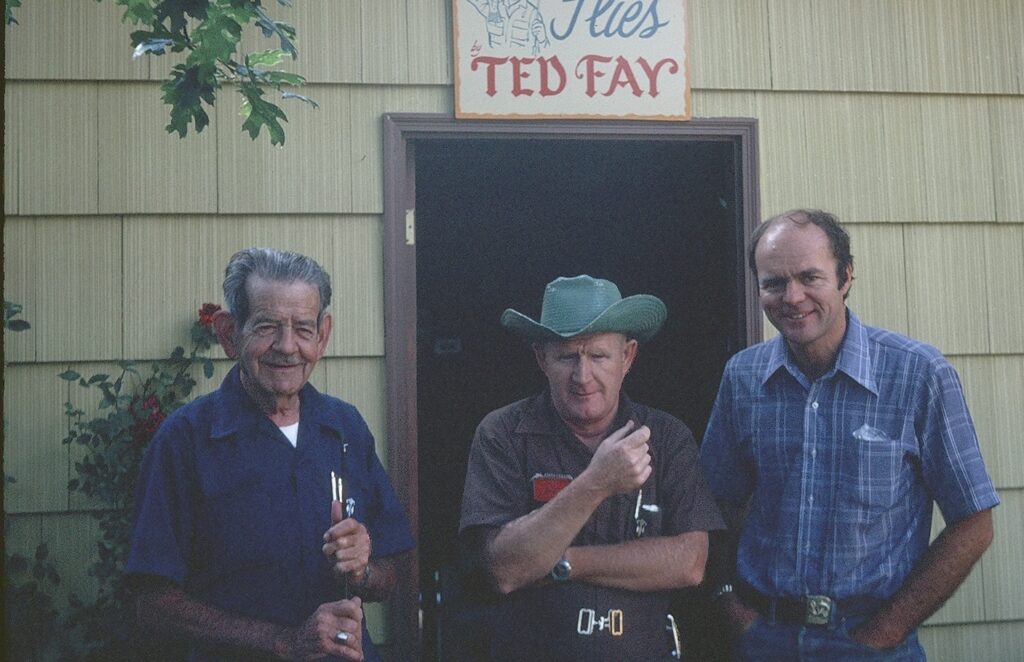

What other changes have stuck with you? The biggest loss I feel personally, even bigger than the decrease in numbers of fish, has been the loss of the old timers—men like Ted Fay, Polly Rosborough, Jay Fair, Cal Bird, and Walt Vaughn. They were different than most of today’s more sophisticated fly anglers. These guys were down-to-earth and generous—men spawned by the country at a time when it was possible to be less influenced by city lifestyles and values. They developed unique ways of fly fishing from years of on-the-water experience without the quick-learning advantage of a podcast. If he were still alive, my uncle would have said that “the dudes” have now taken over the sport. I just feel so fortunate to have known those men from that different time and been able to share stories and laughs with them. As I look back, those moments were precious.

The equipment has continued to change as well throughout the history of fly fishing, and certainly over my 75 years. I have asked myself what new equipment innovation most changed fly fishing during my time. I thought about indicators, fly rod materials and types, large-arbor reels, wader technology, but believe that what changed fly fishing the most was the advent of sinking fly lines. As the technology of sinking lines exploded, we were able to fly fish faster, deeper runs of streams and rivers, reach down into deep lake water with a fly for any number of species of cold and warm-water fish, as well as add important options for a variety of saltwater species. I can’t think of any other equipment change that has opened up so many new options for fly fishing.

Do you have any last thoughts or feelings about your time in the sport? Mostly, I feel an overwhelming sense of gratitude. I’ve had more really good fishing days than one person deserves. I’ve met and fished with so many wonderful people, only a small fraction of whom I’ve mentioned here. I’ve even been honored with a few awards.

The sport has given me the opportunity to experience different worlds—so many types of fly fishing and diverse environments and so many different perspectives—glimpses into business, medicine, research, engineering, and even movie making. Who would have guessed that a young boy who started by crawling on his belly to sneak up on brown trout in quiet water would eventually be able to experience so much wonder?

Editor’s Note: We’d like to thank Mark Likos of Diablo Valley Fly Fishers for sharing the interview conducted by Dan Madison and John Kreiter and encouraging its publication. Also thanks to editor Karen Valentine for distilling the 24 pages of content into an engaging article.