“Val Atkinson has fly fished as many places on the planet as anyone—ever. Along the way he has elegantly captured the places, fish, and people encountered with his camera—moments large and small.”

– Lefty Kreh, American Fly Fisher, Author

The acclaimed fly-fishing photographer Val Atkinson turned eighty this year, and his images continue to define the visual landscape of fly fishing. Many have written about his contributions to the sport and to photography, but Val is more than his body of work. After decades navigating the globe, including 27 trips to New Zealand alone, Val is the fishing buddy we all aspire to have. A sage, sharp-witted friend who fished and photographed every bucket-list destination ten times over, but remains always curious and comedic in his approach to life and imagemaking.

As a young photographer, I was lucky to learn the art of composition through Val’s images (in his words, LCM: Light, Composition, and Moment). Early in my career I worked for Leland Fly Fishing Outfitters, and Val’s photos were the driving force behind our most successful campaigns. I would spend hours wide-eyed, tabbing through galleries from Patagonia to New Delhi. One trip in particular, Kamchatka in 2013, expanded my conception of fly fishing—from bucolic images of smiling anglers in pristine landscapes—into something with grit and high-stakes adventure and Soviet-era choppers. And while pristine landscapes remain central to his work, it’s his ability to transcend beyond the landscapes, into the stories of singular people and places, that has earned Val his reputation as the pioneer of fly-fishing photography.

It was an honor to photograph Val and spend the day revisiting his archives and recounting stories. The following is from our conversation on a sunny February day in San Francisco, beginning at the Golden Gate Angling and Casting Club and winding down in his Inner Sunset apartment where he’s lived since 1972.

So Val, how’d it all start?

I grew up in Ohio in a family that didn’t fish. They didn’t even eat fish, but there I was in a mud puddle, fishing with a stick and a piece of string and a bent pin for fish that weren’t there. So I just had that DNA in me from day one. I have no idea where it came from, maybe my Pisces sign.

And my father was a photographer, that’s how I learned about photography. He wasn’t a professional, but he was a serious amateur. And I got a camera and started taking a few pictures.

What kind of photography did your dad like to do?

Anything, he just liked cameras. He only sold two pictures his whole life to the local bank in Columbus for a calendar. But he was so excited. It still makes me sad, you know. He spent his whole life taking pictures, but he worked a regular job as an auditor for different companies. And my mom was always giving him a hard time. She’d say, “The kids need socks, and you’re spending money on film!”

And that was a big thing, they used to fight a lot and ended up getting a divorce. Our family was dysfunctional, and I got away from the arguments by going fishing in the local farm ponds before high school. “You guys fight all you want—I’m going fishing!” And I did.

I love the portrait you took of your father. Tell me about that image.

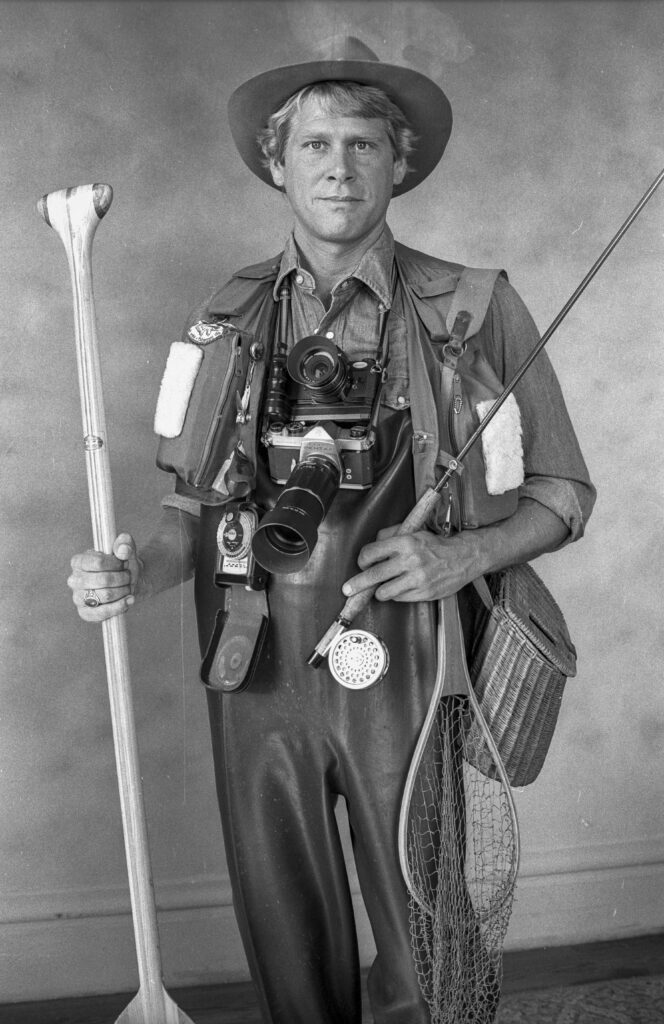

I was just out of art school when I took that. He was a gearhead. He was the opposite of the way I am. Maybe that’s part of the reason why I’m into ‘less is more’. Because he would have the whole trunk full of stuff. He would have a tripod. He would have special snake-proof boots. He would have his whistle in case he saw a bear. He would have his binoculars. He would have a thermos of water and sandwiches. He had a 5×7 Graphlex; it wasn’t an 8×10, but it was big. Just too much shit.

Does that inform your minimal approach?

That’s a good point; I never thought about it but that could be it. I just said, “I hate this photography stuff, look at all this gear you have to lug around.” And then with the advent of 35mm film cameras, you didn’t have to use a big Speed Graphics camera or a Brownie.

How did you make your way to California?

When I graduated from the Columbus College of Art and Design, I went to California because that’s where you wanted to go when you lived in the Midwest: Go west, young man, go west. So California was about as far west as I could go.

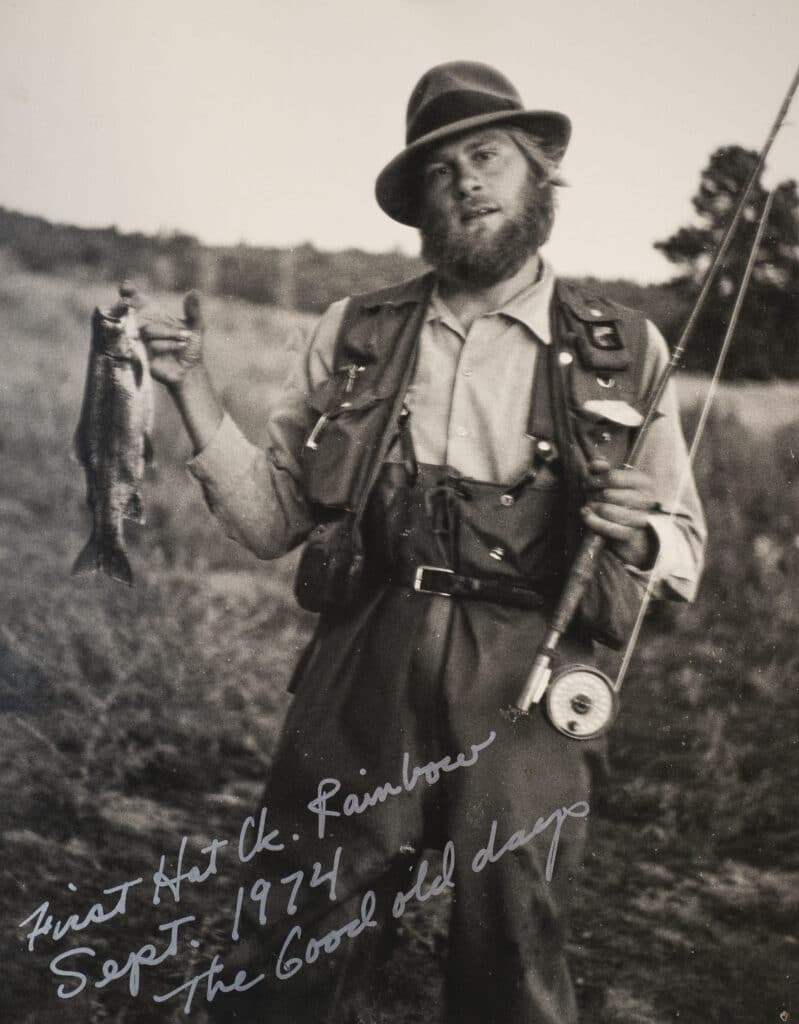

When I was 25, I photographed some friends on Hat Creek for a weekend outing with black and white film. I submitted those to Fly Fisherman magazine and they said, “Wow, these are great. Can we do a photo essay?” So we did, and I got a check for $500. I took pictures of weddings, I did architecture, I did nudes, I tried everything, and nothing really was jiving and I couldn’t make any money. And then when I took those pictures of some fishermen—and I love to fish—and they bought them, it was like, “Holy smokes, that’s what I’ll be—a fly-fishing photographer.”

And people said, “You’re going to be a what? A fly-fishing photographer? What the hell is that?” But I love to do it, and I just kept doing it and getting better and better and better.

Going Global: The Frontiers Era

That gets us to your time with Frontiers Travel. How did that relationship start?

I worked at a television station in San Francisco in the art department. It was a boring job but it paid well. And I heard there was a new company in Pennsylvania called Frontiers International Travel that was looking for a photographer. And I went, “Hell, I’ll go out there.”

I used my own nickel to fly to Pittsburgh. They said, “We’re going to be booking agents for travel. We’ll send you to Christmas Island to see what you can do there.” I’d never even heard of Christmas Island. I didn’t know where it was. I didn’t even have a passport, but I got one.

I’m maybe 30 years old, and I got a passport and went to Christmas Island. It was amazing. I mean, unbelievable. It’s like you’re way out in the Pacific Ocean but there’s no people around and you’re catching bonefish. I never even knew what a bonefish was, but I took some good pictures.

And I came back and they said, “These are great. We’ll use them. You want to sign a contract?” So I signed a contract with them and they said, “Would you like to go to Iceland next month?” We’re going to go to the Laxá í Aðaldal region.” I’d never heard of that either, but I went. I worked for them and they sent me somewhere every month, maybe every other month, for the next 18 years.

Where’d you travel?

Argentina, Chile, saltwater destinations, New Zealand, Russia, just all these places that Frontiers went because there was no competition and everything was new. They were the first booking agent, pretty much. There was Farlows or Hardy’s in England, but not many in America. Nowadays, every fly shop’s got a travel agency. But I was in the right place at the right time, so they took me from going to Hat Creek to traveling around the world.

After those 18 years we finally split ways, but by that time I was pretty established. The big advantage of working with Frontiers is I could take pictures for them, and I could sell them to anybody else as long as it wasn’t a competitor. There were only five or six fly-fishing photographers doing that. So it was easy pickings. You could make a decent living.

You have photos of some of the greats, including Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard. Can you share one of those stories?

I can tell you a cool story from the Rio Grande in Argentina. We were fishing for sea-run trout, and it was Yvon Chouinard, the writer Tom McGuane, and a famous fishing guide, Steve Estella. And because those guys were super luminaries, they had a really special beat on this river. You know, they got in the prime spot at the right time, and we knew it was going to be good. And we were there just in the evening, the light’s really low and there’s no wind, and they started catching them. And they caught something like 22 fish from 15 to 25 pounds on dry flies, bombers, just skating them around. It was unbelievable.

I mean the biggest fish they’d ever seen, even those guys. And a couple of times I said, “Do you mind if I make a few casts?” And the guide said, “No, no, these guys are fishing,” and he wouldn’t let me fish. It really pissed me off. And in the end, I think Yvon Chouinard said, “Val, why don’t you go fish a little bit?” You know, he took pity on me. So I did, and I didn’t end up catching any, and it really pissed me off to watch these guys. But I got good pictures of them.

The Film Days

How did you manage all the gear and film, especially going to places like the Seychelles or Christmas Island?

It was a challenge for one thing, because obviously film is expensive, film is contrasty, and then you’ve got X-ray problems at airports. So we got these lead proof bags and they had to hand-check your film. Film was a pain in the ass, it really was.

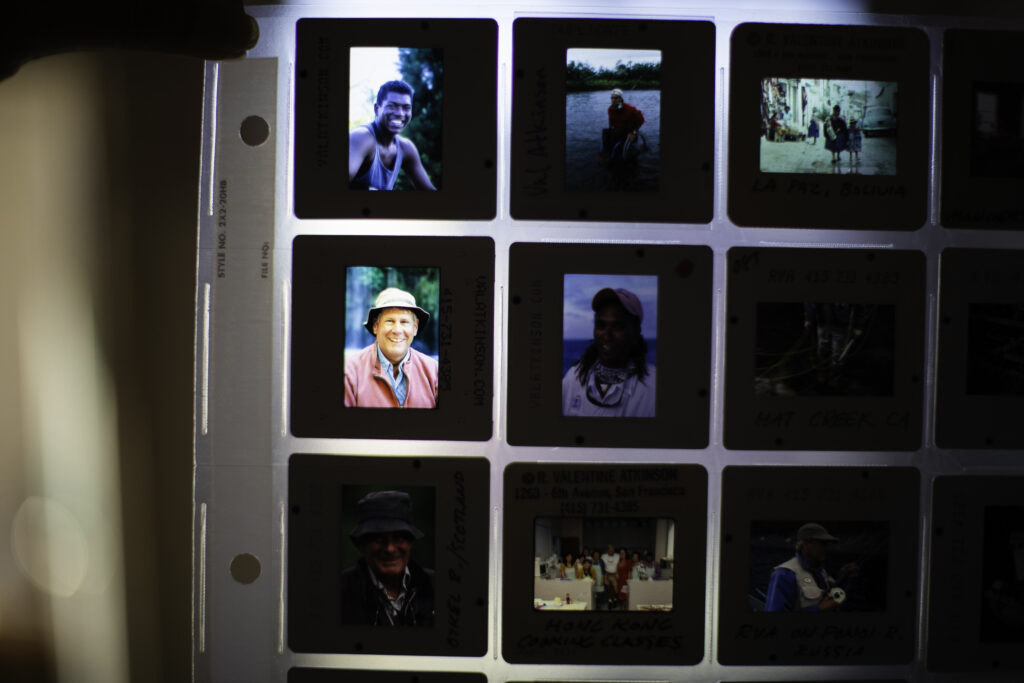

You’ve digitized a lot of negatives. Do you love going back and looking at your slides?

Absolutely. I’ve been to New Zealand 27 times, and I don’t have all of them categorized but I have a few of them on my website from different years. And when I have time, it’s just fun to look at them on a big screen and put them in a slideshow. Memories to last a lifetime.

I have an ability to totally immerse myself in an image, and I can be there. I can look at that picture and I go, “I remember everything about it. I remember what we had for lunch that day.” You know, I might not remember your name, but I can remember what we had for lunch on that rock in New Zealand. So it’s great going back in time, and that’s the beautiful thing about photography.

Have you ever had any film disasters?

Growing up poor, I was always careful with my gear. I had a nice Pelican box. I was careful with my film. I was just always afraid I was gonna lose something or break it. And I didn’t have any backup, so I was always really careful.

But I would take a pelican case with two bodies and two zoom lenses, or maybe one zoom and one fixed focal length. I never had any problem, never lost anything, never never broke anything. I tell people all the time—like you and George Revel are breaking stuff every week—I’ve never broken anything!

Maybe that’s as much a testament to your skill as the photos?

I don’t know how to answer that, other than I just take care of stuff. I’ve got some shoes that I’ve had for 30 years.

And what about fly rods?

I probably have 130 fly rods. I had all these pictures and found out you could sell them to editorial, and they paid next to nothing, or you could sell them to Orvis or Simms or Patagonia, and the price went up. So you start getting hip quick, and start selling to those guys.

Orvis is a good example. I was one of their first main contributors for 10 years, and they’d say, “We got two new rods out, Val, we’re going to send them to you so you can get some pictures.” And at first I started thinking if I’m not going to use it, I’m not going to accept it. But in the end I just said, “send them on,” and they would send me rods every year. I worked for Scott Rods for many years, and part of my contract with them was that I got two free Scott rods a year. So I probably have 40 Scott rods.

They would send you gear, not only gear, but jackets, waders, boots. And there was a saying for a while, “We can’t eat jackets, dude. How about some f—g money?”

Marcelo Perez of Untamed Angling in Bolivia jumping a huge Golden Dorado.

A self-portrait of Val with “too much shit”.

Choppering into a remote New Zealand headwaters stream.

Little Man In Big Nature

I recognize a Val Atkinson photograph when I see one, but what is it about your images that makes them your own?

I like classical things. I like classical clothes. I’m a classical romantic. I think the idea of the Old English style of fishing is really cool.

And I like good light. When I do photo workshops, my mantra, or my credo is LCM: which stands for light, composition, and moment. So if you can get the good light, that makes a good picture. If you can incorporate composition with it, and then you get a moment—like a jumping fish and good light with good composition—that’s a wonderful image.

And I like to tell a story with my pictures. When I first went to Africa, everybody told me to get a 600mm telephoto and zoom in to get the lion picture head-on. And that was great, but I wanted to show the lion in context, so I started gravitating towards a wider angle. To back off a bit and show “Little Man in Big Nature.” That’s something my partner Susan came up with: “Little Man in Big Nature.” You show a picture of someone hiking in the middle of the Alps, and he’s down here and the Alps are up here, or the Himalayas, or whatever. Little man in big nature. Tell a story with your picture.

I like to say I want my pictures to look like paintings, because when I started in art school, I wanted to be an illustrator or a painter. But I just couldn’t do the painting. I wasn’t as good with my fingers, and I was mechanically minded so I got into the camera. I hear that a lot, “Val, your pictures look like a painting.” That’s a wonderful compliment to me.

I love to go to an art museum, and some of my favorite paintings are the Catskill style, the romantic style of the forest with the big clouds coming in and, you know, all the…

…The Hudson River School painters? That’s my favorite room in the DeYoung Museum.

Me too. I go there all the time. I have a pretty good library, and I made a list of my favorite artists. And Thomas Moran is one of my favorites. He’s just got a dexterity, and I was looking at his paintings last night in a big picture book, and I go, “That f—er is good. I don’t know how you could be that good.” That’s what I want my photography to look like.

Now, I’m gravitating away from fishing into just landscapes, and I love that.

And Fall River is the backdrop for your recent landscapes?

I’m spending more time up there. My circle right now isn’t the far corners of the world, it’s my backyard, which happens to a lot of older people. I can go out in my backyard in Fall River and photograph an old apple tree in the light or a bear in the tree, and be just as happy as going to Christmas Island and photographing bonefish.

Well, it doesn’t hurt to have world-class fishing in your backyard.

No, that’s true. I like to go up and cut grass, putter around the house, fix things, and then go fishing. My moral is that I work for two days and fish for one day. Two and one.

Let’s talk about your partner, Susan Rockrise. She’s central to many of your images and adds so much richness to your work. Tell us about that?

She’s worked with Steve Jobs, Andy Grove, and Doug Tompkins among others. Huge people. I mean, she’s a lot smarter than me. She’s at 100 and I’m down at 20, you know? I can’t even keep up with her. She loves people, she’s a real people person.

And what’s it like to have a creative partner who enjoys traveling and is also a great photographic subject?

It’s challenging, because our adventures are different. I want to go somewhere out in the country, she wants to stay in the city and do the city thing. She’s definitely into people. And I’m into searching for dreams in beautiful light.

But she’s always pushing me to do something different, you know, try a different angle, try something new. And I know a lot of times I get stuck in what I like to do, and it shows as a style. She was very instrumental in getting me to push the parameters of, you know, the outer envelope. And she’s always been a really good model.

On Fly Fishing in California

Fly fishing has evolved a lot since you got into the industry. What’s your take on those changes?

It’s gotten more creative, more commercial, more chaotic, more … more of everything, you know? By 100. But then everything else has too, like social media, everything is more and more and more. I think we need to get back to simplifying things. But, you know, I was just as happy when I had one or two fly rods as when I had a hundred.

What about California? When you first came here, where was fly fishing relative to what it is today?

Well, it was less populated. More people are fly fishing now. It seems like there are a lot more people on the water. Like Fall River has quadrupled over time. Better equipment. I’m catching more fish than I did years ago, because I think I’m a better fisherman. Different kinds of lines, different kinds of flies, knowing where to go. So even though there’s more competition, I think I’m doing pretty well.

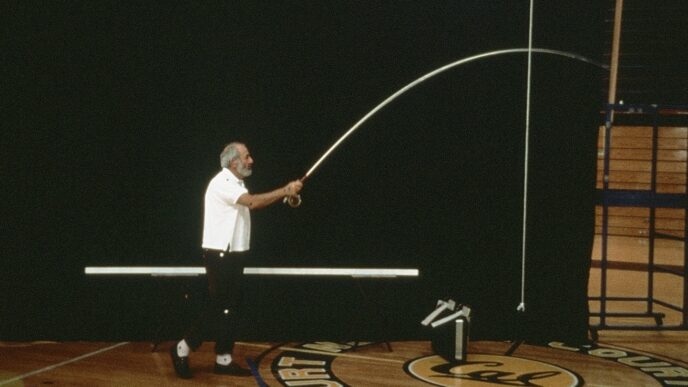

Val Atkinson at the Golden Gate Angling and Casting Ponds. Photo by David Dines

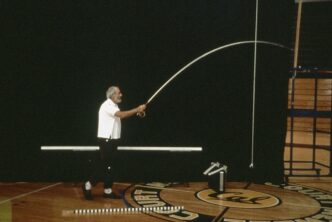

We’re having this conversation in the Golden Gate Angling and Casting Club clubhouse. How does this place fit into your story?

I learned to cast here at an early age, when I first came to San Francisco, after I submitted my black and white pictures of Hat Creek to Fly Fisherman magazine.

This is where you learned to cast?

Yeah, absolutely. Steve Rayjeff and all the experts grew up here. I mean, this is the best casting facility of its kind in the country, and there’s a lot of famous history.

It’s pretty neat to be here after all those years. The place where you learned to cast, went on to have a successful career, and now you’re back and on the board.

Yeah, it is. It’s wonderfully fulfilling. I love it, and it’s nice to have a little bit of respect from people after all these years. Don’t take this the wrong way, but I meet people and every time I come out here they go, “You’re Val Atkinson, you’re famous!” And I go, “No, I’m not famous. I’ve just been doing it for so long and staying dedicated.”

What has kept you so dedicated to photographing fly fishing?

The one thing about editorial photography, even though it doesn’t pay a lot, you get your name in print. That was kind of fun coming from being nowhere in the middle of the Midwest. Coming to California and submitting to magazines and seeing your name in print, you go, “Wow, that’s pretty cool.” It may not sound like a lot, but it’s kind of fun. And you build up your reputation that way.

Val’s Legacy & Looking Forward

What if you hadn’t gone to Hat Creek and shot those black and white photos, what if you’d photographed models in San Francisco? Could Val Atkinson have become a fashion photographer?

Yeah, and I love fashion. I often think that would have been great. Pays better, haha. I love being in a studio, and I don’t mind lights and taking pictures of beautiful models—or ugly models—whatever. It just sort of evolved. And I happened to be a fisherman, and I said, “Well, this is pretty fun, you know? I mean, just taking pictures of people around the campfire. You go out and photograph the weekend.”

And finally, you’re about to turn 80? What’s that like?

Well, almost 80 feels pretty profound, you know, because I know that the average American male lives to 76. So I’m already a few years older than the average person lives.

But you’re not average.

Well, okay, that’s what my doctor says. “You know, you’re in good shape.” But nevertheless, you think about it.

But I’ve discovered a new thing. I walk over to the Arboretum in Golden Gate park every couple days. I get up at 6:30, get a latte and walk three blocks to the Arboretum. They open at 7:30, and I’m one of the first people inside. And on a sunny day, when the light is coming up and it’s starting to dapple through the trees, and the magnolias are out, or different camellia bushes and flowers are blooming, and all the light and the shadows—it’s a religious experience to me.

You know, I call Susan and I say, “You won’t believe it, I’m over here in the park again, and I’m just trembling with excitement. It’s just so beautiful.”

More on Val Atkinson Visit Val’s website to see more of his work and purchase prints, or book one of his photography workshops or his picturesque Fall River Cabin: www.valatkinson.com. Follow Val on Instagram to see his latest photography and highlights from his archives.

Visit Val’s website to see more of his work and purchase prints, or book one of his photography workshops or his picturesque Fall River Cabin: www.valatkinson.com. Follow Val on Instagram to see his latest photography and highlights from his archives.

Great article thank you, love Val and his work. It must have been fun for you to take photos of him.