Piru Creek is a designated Wild and Scenic River that snakes through the mountains northwest of Los Angeles. Not so long ago, it was filled with a lot of large trout. It was my “Curtis Creek,” the stream on which I learned to fly fish and on which I taught my sons, now avid fly fishers, how to fish. As Sheridan Anderson noted in his primer The Curtis Creek Manifesto, there are valuable lessons to be learned on a small stream that can be transferred to larger waters. Unfortunately, Piru Creek in the future may not provide these same opportunities for others, their kids, and their grandkids. However, there is also a chance for this creek to become an exceptional blue-ribbon trout stream.

I started fishing this stream 30 years ago and fished it extensively and intensively for about 20 years, but took a 10-year hiatus, only to fish it recently after the stream’s watershed experienced a major wildfire, the Department of Fish and Game stopped stocking it, and the local dam operator was permitted to restrict flows into the creek. This is an account of my past and recent experiences and of some of the lessons I’ve learned on this creek. More importantly, this is an account of what happened to this stream and what may happen.

The Creek and Its Environs

Piru Creek (pronounced “pie-roo”) can be divided into three parts: the reach upstream of Pyramid Lake in Los Angeles County, the middle portion, between Pyramid Lake and Piru Lake in Ventura County, and the section below Piru Lake. This article concerns the 18-mile middle part. This reach can be further divided into three sections: the area at and two and a half miles above Frenchman’s Flat, the canyon section downstream of Frenchman’s Flat, and the lower reach above Blue Point Campground, near Piru Lake.

The Frenchman’s Flat area is accessible via the Templin Highway off-ramp on Interstate 5. The creek at and upstream of the Frenchman’s Flat parking area is the most accessible of the three sections of middle Piru, since the creek is adjacent to the road. The road is gated at the Frenchman’s Flat parking area, so some walking or biking is needed to get to the upper reaches, where the catch-and-release section (artificial lures only, zero bag limit) is situated above a concrete weir.

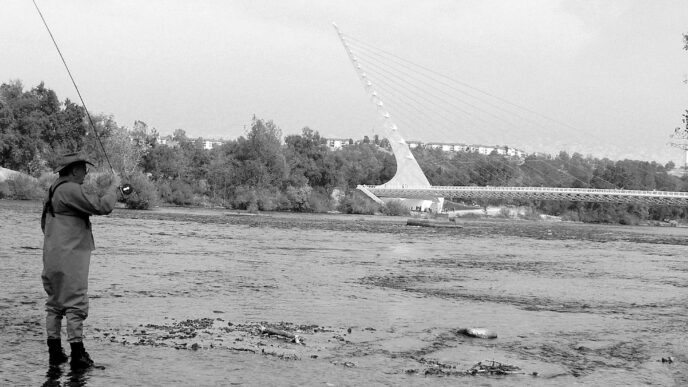

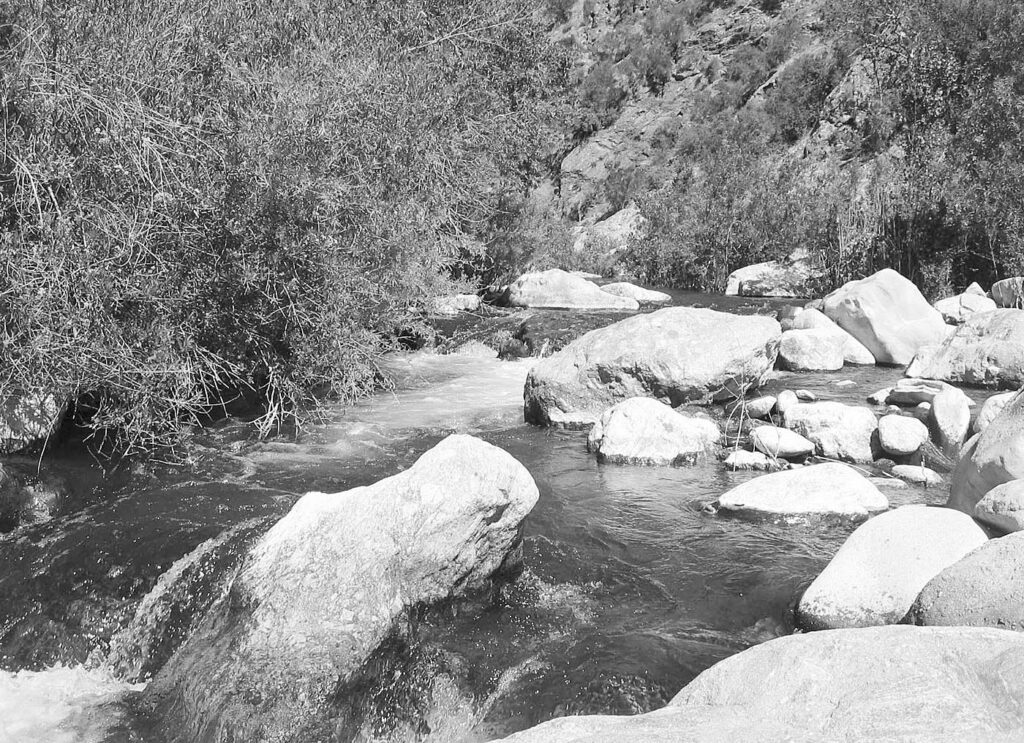

Although the creek’s morphology and flows vary, the stream generally has the width of a one-lane or two-lane road and a depth of about one or two feet. The upper reaches of the catch-and-release section are strewn with boulders, which create some pools, but downstream from there, the creek generally runs straight and narrow through a thickly wooded gorge, making access to the water difficult. The area adjacent to Frenchman’s Flat is relatively open, providing easier access. However, as with many streams next to car-camping areas, the creek there is literally trashed.

Official designations aside, the canyon section downstream from the parking area is the real wild and scenic section, with the emphasis on the wild. As this freestone creek meanders through the canyon, it ricochets off the steep walls, creating deep pools. Between the pools created at these doglegs, the stream courses through galleria forests, deadfalls, and cattail thickets alongside rocks and huge boulders. These conditions make a safe haven for trout, but also make the stream challenging to fish.

The canyon in this area is narrow and deep, with vertical differences of generally 1,400 feet to 3,000 feet from ridgetops to the canyon bottom. As a result, sunshine comes late to the canyon and leaves early. The extended shady periods, along with the dense riparian growth, may help keep the stream cool in the summer, aiding trout survival in an otherwise semidesert environment. The deep canyon also protracts the twilight period, which is a magical time for fishing on this stream.

The lower reach of middle Piru is still part of the canyon section, but since it is remote from Frenchman’s Flat and more accessible from Ventura County, it is regarded as a separate section. The canyon broadens out in some areas upstream of Blue Point Campground, but otherwise, it is as rugged as the northerly portion of the canyon. In my experience, this lower reach has better fishing than the reaches above and below Frenchman’s Flat, but it is the least accessible of the three sections of middle Piru, because it requires a seven mile hike or bike ride from the Piru Lake parking lot to Blue Point.

Fishing Piru Creek

Piru Creek is a challenge to fish for several reasons. First, it is physically demanding. In most places, you need to climb and descend steep canyon trails, scramble over boulders, and fight your way through deadfalls and thickets just to get to the water. Fishing it requires wet wading during any season if you intend to cover the stream effectively, because the trail, where one exists, is often interrupted, causing you to ford the stream. Moreover, there are many situations in which you can fish only by getting into the water.

The second reason why fishing this stream is a challenge is that it requires stealth, and stealthy approaches are particularly difficult on Piru Creek because of the streamside tangle. Bushwhacking to get to the water’s edge causes a lot of commotion. In lieu of bushwhacking, you could advance upstream or downstream by wading, but this is the antithesis of stealth. Sheridan Anderson promotes various techniques in his manifesto, one of which I tried in the past — the “Curtis Creek Sneak.” This is essentially crawling in the water downstream of a cascade, then flicking a fly onto an elevated pool. Yes, this really works. “If you think all this creeping and crawling a bit ludicrous,” Anderson says, “you’ll get over it!” Few anglers, however, are willing to employ the stealthy approaches espoused by Anderson.

The third reason why fishing middle Piru is challenging is that it requires a unique set of casting skills. To fish Piru Creek effectively, you may need to employ the bow-and-arrow cast, the wye cast, the steeple cast, and dapping, as illustrated in Anderson’s cartoonlike book. The roll cast and sidearm cast are also particularly useful on this tight stream. So fishing Piru Creek forces you to hone your skills, thereby making you a better fly fisher.

One technique I’ve found viable on this stream and on other streams that flow through a tunnel of vegetation violates one of Anderson’s 11 commandments: “Thou shalt fish upstream.” It is drifting a fly downstream as a dry and stripping it back as a streamer. The fly I like for this job is the traditional Royal Trude, tied with sparse hackle. This gives you two shots at trout in the hard-to-reach spots. After bushwhacking your way through the riparian tangle, drift the Trude downstream. If you get no takes, give the line a sharp tug to submerge it and strip it back as a streamer. Occasionally, the dry fly will get intercepted, but most likely, the Trude will entice a hit as a streamer. As always, it is important to be stealthy, so try to stay on the bank when doing this. If you need to get in the water, slip in slowly and quietly and position yourself near the bank, rather than midstream.

Tackle for Piru

For the downstream technique with the Royal Trude, you can use a very long leader and, of course, a floating line. However, for small streams such as Piru, usually short leaders of 7 to 8 feet, including a 4X or 5X tippet, are sufficient. The relatively heavy tippets are to save your flies, which will invariably get tangled in leaves and twigs. Rods, of course, should be short, 8 feet or less, and light. I use a 4-weight, because I like to fling small Woolly Buggers, as well as dry flies. Lighter rods, 3weights, 2-weights, and 1-weights, were made for dry-fly fishing on small streams such as Piru. When fish are looking up, the old standbys, such as a size 16 Parachute Adams or Elk Hair Caddis work well. At other times, small Woolly Buggers will get you some action.

We all know that one should let the water or conditions dictate which flies or methods to use. I violate this principle often, since I generally do not fish nymphs as a matter of preference, but sometimes, a nymph may be the optimal fly. The largest fish I ever caught in Piru Creek had someone else’s size 14 nymph (of a kind I had never seen before or since) clipped to its jaw. So I know nymphing can be extremely effective on this water. What is a good nymph to use on this stream? Anderson says, “a hot shot angler can probably do pretty well anywhere in the country armed with nothing more than a #16 gold-ribbed hare’s ear.”

Precautions

If you intend to fish middle Piru, especially the canyon area below Frenchman’s Flat, remember that it is indeed a wild and rugged area. Take precautions, as you would when hiking into any wild place. Although I have not always gone with a companion into the canyon, it is sound advice. There could be serious problems if you were to sprain an ankle or back while alone in the canyon. When planning to fish alone, tell a responsible person exactly where you intend to fish and when you intend to return.

As indicated previously, be ready to do a lot of wet wading and boulder climbing, so wear lug-soled boots that drain easily. It is also a good idea to pack in plenty of water, especially if you go during the warmer months. If you intend to fish at twilight, the magical time on this water, be sure to take a flashlight. I’ve stumbled out of the canyon by starlight — it is no fun. Although I’ve never seen any rattlesnakes in all my trips into the canyon, this is rattlesnake country. Always watch your step. For me, the constant threat in the canyon is poison oak. Poison oak seems to grow in clumps any place that gets sufficient water to support it, so I try to avoid those areas and anything that looks remotely like that insidious plant.

A potentially lethal hazard you do not want to encounter in the canyon is flash flooding. Once, my college-age son and I decided to camp in the canyon when there was a forecast of possible showers. Big mistake. Our tent was pitched on a high embankment, but I spent a restless night listening to and periodically observing the roaring river below us. We spent the next day trekking out of the canyon, seeking out the broader, shallower — that is, waist deep — portions of the creek to ford, carrying our backpacks over our heads like safari porters. Moreover, you may not know when the dam operator will release torrents of water into the canyon during the rainy season, so you may want to avoid this stream then.

As you can see, fishing Piru Creek is not for everyone. But if you appreciate the wild beauty of nature and don’t mind a strenuous workout and challenging fishing, the middle section of the stream may be for you.

Years Ago

In the past, I fished every stretch of this 18-mile section of the creek, camping in the heart of the canyon to do so. It was common to catch 30-plus fish a day, with a handful around 12 inches. This success was probably due not to my fishing prowess, but rather to the California Department of Fish and Game’s annual stocking of 3,000 pounds of trout at Frenchman’s Flat. The largest trout I caught was a 16-inch rainbow, though the largest fish I witnessed a buddy catch was 17 inches. There are reports of larger fish. Joe Richey, who has one of only two homesteads on middle Piru, located above Blue Point, reports similar results and says that catching fewer than 40 fish per day used to be a disappointment. Fishing was that good.

But that was before the 2006 Day Fire. This wildfire, which was the sixth largest in California history, burned the watershed of Fish and Agua Blanca Creeks, two major tributaries to middle Piru. One consequence of this fire was that it changed the stream morphology and devastated the aquatic insect communities downstream of Fish and Agua Blanca Creeks. Gone for now are the blizzard hatches of mayflies and caddisflies and, consequently, the good fishing. The stream downstream of the Fish and Agua Blanca confluences will eventually recover from the fire, but Richey’s fear is that things will get worse due to recent government regulations. I’ll discuss these below.

Recent Outings

After a 10-year hiatus, I fished the canyon section below Frenchman’s Flat in late spring of this year. It is axiomatic that the better fishing is found farther from the road, and this is especially true with small streams, so I decided to hike a couple of miles into the canyon. The water was surprisingly high, yet the stream was fordable. What struck me immediately was that the vegetation was thicker than I had remembered. Some parts were not recognizable.

Most importantly, the fishing, or rather the catching, had changed. Candidly, at first, I was concerned that there might not be any fish in this stream, since Fish and Game had stopped stocking it years before, and this water is pounded by bait anglers who tend to kill their catch. So I was delighted to catch my first fish — a 9-inch rainbow. Unfortunately, as the day wore on, the large numbers and especially the size of fish did not materialize as they had in the past. I caught (and released) 15 rainbows in the 7-to-10-inch range, but I really had to work for them. The large pools, which usually produced at least a couple of larger fish in the past, produced none. The rare open stretches of the stream that were easily accessible also did not produce any fish. After a while, I didn’t even bother fishing them. These spots seemed fished out.

Admittedly, this observation is not definitive. Perhaps a real creeksmith with the right nymph and technique could have dredged up some fish from these spots. But comparing the techniques that worked for me in the past with those I used recently, these easily accessible spots seemed depleted; the limited success that I did have could be attributed to fishing only the hard-to-reach stretches of the stream, those protected by thickets of undergrowth, trees, and boulders. Bushwhacking through riparian thickets all day just to get to the water is punishing work. Still, this is where the fish are — in challenging situations, places that are overlooked by most anglers. Again, these fish were small, making the effort seem a Pyrrhic victory.

In the early summer, I fished the catch-and-release section above Frenchman’s Flat. As with my prior adventure, I fished from midmorning to late afternoon. The results were similar to my earlier excursion, except I caught fewer and smaller fish. What was surprising was the jumble of deadfalls and riparian growth. These had been bad in the past, but I didn’t remember them as being virtually impenetrable. Once at the water’s edge, it was often easier to trudge upstream in the water than to fight the streamside tangle, but this only sent the few fish before me scurrying to the next county. Besides this, wading in this section is treacherous, due to the algae-covered substrate. Again, this stream is not for everyone. As indicated previously, one could make the case that fishing this creek is hardly worth the effort, but as you will see below, in fact, it could be well worth it.

I was not surprised to find evidence of poaching in this no-kill section. Some anglers had left behind Styrofoam worm containers alongside some of the large pools, thereby compounding their sin of poaching with littering. So these more accessible pools in the catch-and-release section have probably been hammered. I remember that my young sons in the past would sit on streamside boulders next to these holes, drifting Hare’s Ear Nymphs in the current, and nearly every time that the nymphs ascended at the end of a drift, they would get a hookup. That was not the case during my recent outing. Again, this account of “catching” is not definitive, but it sure seems, as one old-timer once told me, “It ain’t like it used to was.”

Political Wrangling

Why did this fishery change, and what is its future? Here’s the situation in a nutshell, albeit a very large nutshell.

When Pyramid Lake was constructed in the mid-1970s, the operating license required that the Department of Water Resources (DWR), the dam operator, release minimum sufficient flows to maintain a fishery in middle Piru Creek and to stock the creek with trout. As a result, the California Department of Fish and Game stocked 3,000 pounds of trout in the stream yearly at Frenchman’s Flat.

In 2005, the Department of Water Resources and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, which shunts water from Pyramid Lake to generate electricity and subsequently to supply water to Castaic Lake, applied to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to modify the original operational license to revise the flow regime and the stocking program. Specifically, the proposal to amend the flow regime amounted to matching the outflows from the Pyramid reservoir to the inflows. This would result in the release of torrents in the rainy season and low volumes during the dry season, with possibly periods of no surface flow in middle Piru during the summer.

This proposal was ostensibly to protect the arroyo toad, which inhabits the canyon upstream of Piru Lake. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service designated the arroyo toad an endangered species in 1994. However, the FWS concluded a five-year study in August 2009 in which they studied 20 arroyo toad populations in Southern California and recommended that the arroyo toad be delisted from endangered species to threatened species. Despite this recommendation, in February 2011, middle Piru was classified as “critical habitat” for the toad.

Organizations such as California Trout, Friends of the River, local fly-fishing clubs, and others were concerned that the low or no flows through the canyon, among other things, would, obviously, be inimical to the trout in the creek. CalTrout and Friends of the River challenged the proposed flow regime, since it was based on readings from two gauging stations upstream of Pyramid Lake and did not take into account water that is diverted in the watershed upstream of the lake, nor did it adequately account for water entering the huge Pyramid Lake reservoir via minor tributaries and seepage. Thus, outflows based on two gauging stations may not match the true, natural inflows. Moreover, Friends of the River, CalTrout, and other conservation groups claimed that the revised flow regime may not clearly be optimal for the arroyo toad, since alternatives were not studied, and that the proposed flow regime may adversely affect other endangered or threatened species inhabiting middle Piru Creek and its canyon.

Before FERC could issue the minimum-flow amendment to the dam operator’s license, the Clean Water Act required that the California State Water Resources Control Board grant a certification. The water board issued the certification in December 2008, but it was challenged by Friends of the River and CalTrout. The water board, however, concluded in August 2009 that the certification was appropriate, but added a statement of “overriding consideration” that acknowledged that the amended license would reduce angling opportunities in Piru Creek. On October 28, 2009, FERC issued an order amending the DWR’s license and eliminating the minimum-flow requirement. CalTrout and Friends of the River filed a lawsuit challenging the certification in December 2009.

The amended license also required the Pyramid Lake dam operator to file a plan and address the fishery in Piru Creek until the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the DFG can make a final determination regarding future fish stocking practices. The plan was to be prepared within 120 days, but it has been delayed because a 2006 lawsuit by the Center for Biological Diversity and the Pacific Rivers Council requires the DFG to prepare an environmental impact report on its stocking programs’ effect on native trout and amphibians. This lawsuit has affected many waters statewide. The DFG cannot make a final determination for Piru until the statewide issue is resolved. Extensions have been requested until this mess is sorted out. Until then, there will be no stocking of middle Piru, and there has not been since August 14, 2008.

In March 2009, about seven miles of middle Piru in Los Angeles County downstream of Pyramid Dam was designated a Wild and Scenic River. This was due to the efforts of Friends of the River and CalTrout with the support of U.S. Representative Buck McKeon. The canyon and river are also wild and scenic in Ventura County, in the generic, descriptive sense of the terms, but the L.A. County section is in the jurisdiction of Congressman McKeon, whereas the Ventura County part is not. The Wild and Scenic designation affords certain protections, one of which — one would presume — would be flowing water. Still, FERC approved the amendment to eliminate the long-established minimum flows.

Fishing Surprise

Other relevant events occurred before FERC’s relicensing of the Pyramid Lake dam. In 2006 and 2008, two scientific studies were completed that are of particular interest to fly fishers. These scientific analyses, based on highly variable genetic markers, were used to trace ancestry and evaluate genetic distributions in populations of steelhead trout in Southern California, including Piru Creek above and below the Piru Lake dam. These studies showed that for the most part, there is no significant genetic difference between steelhead below and above barriers such as dams. According to the 2006 study by Derek Girman and John Carlos Garza, “trout breeding in streams tributary to the dam reservoirs are recently derived from a common ancestral population with trout populations breeding below the dams.” Moreover, surprisingly, there is little evidence of intergression or interbreeding of the hatchery-stocked trout and steelhead strains above dams, according to Girman and Garza. The 2008 study by Anthony J. Clemento and others, which also focused on south-central California steelhead, confirmed the Girman-Garza study: “Absence of hatchery fish or their progeny in the tributaries above dams indicates that they are not commonly spawning and that above barrier fish are descended from coastal steelhead trapped at dam construction.”

To me, this is exciting stuff. It means that the little fish I caught recently, which were too small to have been planted, were descendants of the same fish that swam in the creek when mastodons and sabertoothed cats roamed the L.A. basin. These same ancestral fish were likely hunted by paleo-Indians, and now I — we — have a connection to them. This made my recent arduous efforts worthwhile — the realization that these little fish are steelhead — steelhead, by the way, that could grow to impressive size if given a chance. According to Nica Knite of CalTrout, resident steelhead typically grow to 14 to 18 inches, and sea-going steelhead can grow to 24 to 30-plus inches. One can only imagine what it would be like to cast a fly to very large steelhead in Piru Creek.

The Future

As indicated above, CalTrout and Friends of the River filed a lawsuit against the water board. The suit is now on hold while the conservation groups and regulatory agencies discuss a possible settlement. Essentially, the water board is open to increasing the flows into the creek if the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agrees. CalTrout and Friends of the River are seeking to achieve a balanced approach to the flow regime for the benefit of all endangered and threatened species and steelhead trout. So it appears that there is a chance that middle Piru Creek may continue to flow during the summer, thereby ensuring the viability of the steelhead fishery, but this is in no way guaranteed. Whether or not the creek dries up may depend on the outcome of this settlement. Readers may want to contact California Trout, Friends of the River, or their local fly-fishing clubs about this matter.

The steelhead trout in the creek are not considered “endangered” by FERC because they are not sea-going. However, this, too, may change in the future. In 2002, the United Water Conservation District applied to FERC to renew their license for the hydroelectric project at the Santa Felicia Dam at Piru Lake. FERC issued a new license on September 12, 2008. However, due to protracted and contentious negotiations between United Water and the National Marine Fisheries Service, in which the NMFS prevailed, the requirement of a “biological opinion” was imposed, recommending “reasonable and prudent alternatives” to the proposed action. This legal document requires the dam operator to provide, among other things, a steelhead passageway around barriers to fish migration. So, the steelhead may ultimately resume their ancient migratory ritual in middle Piru Creek.

A Possible Solution

As it now stands, middle Piru Creek has not been stocked for a few years and may not be for many more years, if ever. The stream experiences intense fishing pressure by bait anglers around the Frenchman’s Flat area. Even the catch-and-release section below the Pyramid Lake dam is subject to poaching. Also, there have been several reports of the netting of trout. Joe Richey once chased off four men who were netting trout near his homestead. It is hard to imagine thisstream remaining a viable fishery under these conditions. This is not to say that there are not some big fish still in the creek, even near Frenchman’s Flat. There may be some large resident steelhead that migrate up from the middle of the canyon. But for the most part, the fishing and the recreational experience will likely be further degraded, since it is a simple fact that taking without replenishment will result in fewer fish.

Since middle Piru Creek is no longer stocked, it would be prudent to designate the entire stream as catch and release until such time the stocking program is resumed. This would certainly enhance the “catching” experience, except for those who fish for meat. Of course, if the current situation continues, there will be very few fish even for them to kill. This program would work only with rigorous enforcement. With heavy use by catch-and-release anglers, a form of enforcement may develop such as occurs on popular catch-and-release streams. Also, the Fisheries Resource Volunteer Corps often patrols this area. They routinely inform people of prevailing regulations. So there could be citizen enforcement to augment the game warden patrols. To initiate a catch-and-release designation, contact Stafford Lehr, chief of the Fisheries Branch of the California Department of Fish and Game, with a copy of the request sent to the Fish and Game Commission. (See the sidebar for contact information.)

With the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s acquiescence, a favorable settlement of the Friends of the River/Cal Trout’s lawsuit with the water board may result in a guarantee of minimum flows in Piru Creek during the dry season, thereby enhancing the survival of the resident steelhead. And due to the efforts of the National Marine Fisheries Service, the fish passageways on lower Piru will allow the sea-going steelhead again to spawn in middle Piru. With no-kill regulations in place, middle Piru could become a truly exceptional blue-ribbon trout stream. The more accessible areas of the creek around Frenchman’s Flat could become a place for seniors, youngsters, and those with physical limitations to fish with a reasonable expectation of catching some sizeable trout. Access in the rugged areas would surely improve as many others would beat a path along the stream, pursuing large steelhead. So this stream may still become a “Curtis Creek” for others, their kids, and their grandkids. There is a rare opportunity here to leave a fishery for future generations better — much better — than we found it.

Contact Information

Stafford Lehr, Branch Chief

California Department of Fish and Game, 830 S Street, Sacramento, CA 95811 Phone: (916) 327-8840

California Fish and Game Commission

P.O. Box 944209

Sacramento, CA 94244-2090

Phone: (916) 653-4899

Fax: (916) 653-5040

E-mail comments on proposed regulations to fgc@fgc.ca.gov with subject in the subject line

Jerome Buckmelter