GEOLOGY – PYRAMID LAKE

By Jeff Ludlow

Illustrations by Obi Kaufmann

The tufa rocks of Pyramid Lake stand as a legacy to the Ice Age when the ancient Lake Lahontan once covered an enormous area of northwestern Nevada comparable in size to Lake Ontario. During the late Pleistocene epoch approximately 26,000 to 13,000 years ago, the climate was wetter and colder. Glaciers and rivers flowed from the mountains, and springs rich in calcium seeped into the ancient lakebed where they reacted with carbonate in the water to form tufa. As lake levels receded after the ice age, the whitish buff-colored tufa rocks became visible around Pyramid Lake. Rising above the current waterline, Pyramid Lake’s tufa represents one of the largest deposits of this unique geologic formation in the world.

Pyramid Lake is a pluvial lake, existing in a closed basin with no outlet. Water levels in pluvial lakes are influenced by precipitation and evaporation. For Pyramid Lake, the Truckee River serves as its only inlet and primary water source. Prehistoric shorelines of Lake Lahontan are still visible in the mountains above Pyramid Lake, marked by horizontal strata of lacustrine marls—carbonate-rich mud benches formed at the ancient lake’s shore.

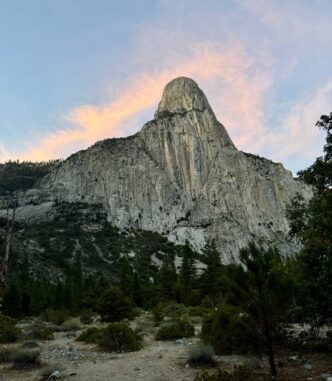

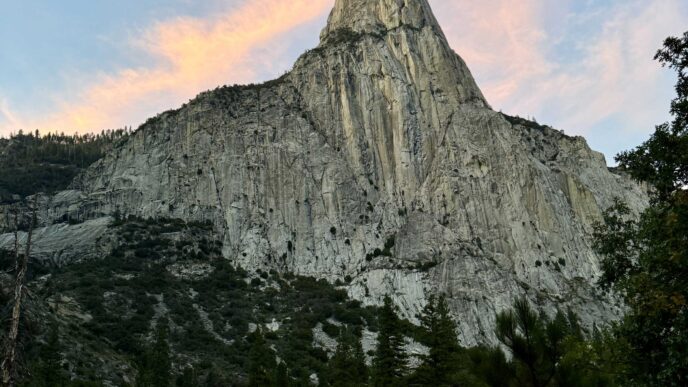

The lake received its name in 1844 from John Fremont, who described its most striking feature: the pyramid-shaped Anaho Island off the lake’s eastern shore. The Paiute call the island Wono, meaning “cone-shaped basket,” and refer to the lake as Cui-Ui Panunadu, meaning “fish standing in water.”

Pyramid Lake lies at the western edge of the Basin and Range Geomorphic Province, a vast region covering much of the inland western United States and northwestern Mexico. Characterized by alternating mountain ranges and desert basins, the region’s topography was formed by tectonic extension beginning in the Miocene epoch, around 17 million years ago. As the Earth’s lithosphere (its crust and upper mantel) stretched and pulled apart, north-south-trending fault blocks formed across the entire region. This process created the “horst and graben” landscape: Horsts are uplifted fault blocks, while graben are down-dropped blocks, resulting in the alternating basins and ranges of the region.

The tectonic mechanism that caused the stretching and thinning of the lithosphere in the Basin and Range Province is complex and controversial. One theory lies with California’s own San Andreas fault. Unlike the vertical movement of faults in the Basin and Range Province, the San Andreas is a strike-slip fault, where the Pacific Plate (west of the fault) moves laterally northwest relative to the North American Plate (east of the fault). This lateral movement is thought to be pulling on the crust of the North American Plate, causing it to stretch and fracture into the fault blocks of the region. The other prevailing theory suggests that magma rising from beneath the lithosphere in the interior of the western United States creates upward pressure, bulging, stretching, and thinning of the crust, thus creating the fault blocks.

Returning to Pyramid Lake and its ancestor, Lake Lahontan: During the Pleistocene epoch, this enormous Ice Age lake supported ecosystems that hosted a striking variety of animals not found in the region today. Mammoths, giant ground sloths, camels, shrub oxen, horses, cheetahs, and other extinct mammals are known to have inhabited Nevada during this time.

And what lived in the waters of ancient Lake Lahontan? Most notably, Oncorhynchus clarkii henshawi, or the Lahontan Cutthroat Trout (LCT). This species evolved in the isolated Lahontan Basin, where the ancient lake ebbed and flowed over millennia. LCT exhibit diverse survival strategies, thriving in streams and lakes with resident, migratory, adfluvial (migrating between lakes and streams), and lacustrine (lake-dwelling) characteristics. The lake form of LCT are uniquely adapted to the saline and alkaline waters of the Lahontan Basin’s pluvial lakes. As an apex predator in the lake, they are one of the largest inland salmonid species on earth.

The Cui-Ui sucker (Chasmistes cujus), the oldest fish species in the Lahontan Basin, is endemic to Pyramid Lake and the lower Truckee River. Once prehistorically prolific throughout the Lahontan Basin, this endangered fish was a very important food source for the Paiute people and remains a key focus of habitat and spawning-ground restoration. Together with LCT, the Cui-Ui is central to Pyramid Lake’s cultural and natural heritage.

U.S. Geological Survey, 2004. The Tufas of Pyramid Lake, Nevada. Fact Sheet 2004-3044. April

Cengage, Gale, 2003. Lerner, Lee; Lerner, Brenda Wilmoths (eds.). “Basin and Range Topography”. World of Earth Science.

Historical Geology. San Andreas Fault and Basin and Range.

Hattori, Eugene, 2009. Ice Age Nevada and Lake Lahontan. Online Nevada Encyclopedia. 18 December.

Western Native Trout Status Report, 2020. Lahontan Cutthroat Trout. July.

BIRDS – AMERICAN WHITE PELICANS

By Tracey Diaz and Bethany Chagnon, Deputy Project Leader, Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge Complex, USFWS

Anglers and American White Pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) often find themselves in quiet competition, both drawn to the same rich fishing grounds. At Pyramid Lake, Nevada, these iconic birds share the waters with fishers, creating a dynamic interplay between sport and survival. For the pelicans, Anaho Island National Wildlife Refuge, at the southeast end of Pyramid Lake, serves as an essential sanctuary, housing one of the largest breeding colonies in the western United States. Each spring thousands of pelicans migrate to Anaho, attracted by the island’s isolation and the lake’s abundant tui chub (Siphateles bicolor), which sustain their young.

The American White Pelican is distinguished by its massive orange bill, which it uses not for diving but for cooperative foraging. Unlike their Brown Pelican relatives,that plunge-dive, White Pelicans often form flotillas, herding fish toward shallower waters before scooping them up. This behavior showcases their dependence on healthy aquatic ecosystems, making them sensitive indicators of environmental change.

Nesting season on Anaho is a delicate time. Pelicans construct nests from shoreline vegetation and rely on uninterrupted habitats to successfully rear their chicks. Disturbance—whether from humans or changes to water quality—can cause nesting failures. While the island is closed to public access to protect the birds, anglers at Pyramid Lake play a role in preserving this balance by advocating for responsible fisheries management and conservation. For anglers who value thriving ecosystems, the presence of American White Pelicans is a reminder of the interconnectedness of wildlife and the waters we all share.

Efforts by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to maintain the ecological integrity of Pyramid Lake and Anaho Island reflect the importance of this refuge in the broader conservation landscape for pelicans and other migratory waterbirds.

USFWS, Pyramid Lake Fisheries Report

Anderson, J. G. T., Biology of Pelicans (2008)

USFWS, Anaho Island National Wildlife Refuge Fact Sheet

Conservation Science Partners, 2022 Report on

Nevada Wetland Ecosystems

About Obi

Illustrator Obi Kaufmann is an award-winning author of many best-selling books on California’s ecology, biodiversity, and geography. His 2017 book The California Field Atlas, currently in its seventh printing, recontextualized popular ideas about California’s more-than-human world. His next books, The State of Water; Understanding California’s Most Precious Resource, and the California Lands Trilogy: The Forests of California, The Coasts of California, and The Deserts of California present a comprehensive survey of California’s physiography and its biogeography in terms of its evolutionary past and its unfolding future. The last in the series, The State of Fire; Why California Burns was just released in September 2024.