Spotlight Destination

I’m balanced on a step ladder, out of the frigid water, staring at my strike indicator bobbing gently on the wind-rippled surface.

I’m among about a dozen other fly fishers all spaced about 40 feet apart, perched in a line at the brink of a deeper drop-off—some on regular step ladders, others sitting on elaborate elevated fishing chairs (specifically designed for Pyramid Lake) wheeled in from the beach. For the last couple of hours there’s been no action. Fatigue and monotony have set in. A cold wind is blowing onshore. My fingers are numb, my back is aching, and my eyes are bleary from hours of intently staring at my bobber. There’s some excitement a few ladders down. A hookup, and I know when the guy and his buddy step down off their ladders to land the fish in shallower water that it’s a big one. I can hear the muffled, excited conversation as they weigh the fish in the net: “16 pounds.” After the obligatory grip-and-grin photo they quickly release it.

I feel a tinge of envy, then look back with renewed concentration just as my bright orange bobber is slowly pulled under. I jerk the rod straight up and immediately feel a solid connection. Big, strong head shakes tell me it’s a good one. The fish feels heavy as a rock, swimming slowly back and forth as if figuring out what to do, then takes off and accelerates toward the middle of the lake. I’m into the backing before I know it, but then the line goes slack. I reel the line back in, dejected, until I’m surprised to find the fish is still on, now wrapping the line around my wife Yvonne’s ladder to my right. I loosen the drag to take tension off the line. The fish makes a tactical error, swims back around the ladder freeing the line, then heads into the shallows, inside the ladder lineup. After a few minutes of chasing the fish around in knee-deep water, Yvonne sweeps the big rubber net under it just as the size 12 barbless chironomid pops out of its jaw. It has a clipped adipose fin, signifying the Pilot Peak strain, a hatchery reincarnation of the original giant Pyramid Lake Lahontan cutthroats, once thought to be extinct.

To call any fish a “fish of a lifetime” is saying you’ll never catch a bigger or better one. But it tapes 33 ½ inches before I release it. In my mind it’s my fish of a lifetime for cutthroat trout.

Located 35 miles northeast of Reno, Nevada, on the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe reservation, Pyramid Lake is 27 miles long and up to 11 miles wide. It is a shimmering turquoise jewel nestled in austere high desert surroundings.

Pyramid Lake is a remnant of ancient Lake Lahontan, which once covered more than eighty-six hundred square miles of western Nevada. After the last ice age, as the climate warmed, the lake receded, leaving behind Pyramid Lake as its largest vestige at the deepest point of the ancient inland sea.

Pyramid Lake has no outlets and, despite being 350 feet deep, is rich in salinity, roughly 1/6 that of seawater. It’s also the terminus of the Truckee River. Flowing a hundred river miles from Lake Tahoe through the towns of Truckee and Reno, the river pours into the south end of Pyramid Lake, infusing it with nutrients and oxygenated water, fostering a generative environment for multitudes of fish.

The late Dr. Robert Behnke, the world’s leading authority on cutthroat trout, described how the Lahontan cutthroat trout (LCT), Oncorhynchus clarki henshawi, evolved to grow to such enormous sizes in Pyramid Lake: “They had a very special adaptation to be a predator on the very abundant population of minnow called a tui chub. And the tui chub in Pyramid Lake gets quite large . . . up to 18 inches. To make use of all that resource, the LCT had to get very large to consume them.”

The Lahontan’s size and numbers were legendary. During the spawning run of 1912, the fish were so numerous in the Truckee River that over twenty thousand pounds of LCT were commercially harvested every week using nets, gaffs, spears, and pitchforks. The Paiute tribe established a cannery, and the delicious fish was shipped nationwide.

According to Behnke, “Fred Crosby, who used to buy and sell

the fish for the tribe, said that in 1913, he once saw a fish that weighed 62 pounds.”

On the freezing cold morning of December 1, 1925, a Paiute man named John Skimmerhorn caught the “official” International Game Fish Association world record LCT, a rotund female that weighed 41 pounds and measured 41 inches in length.

Even with extreme overharvesting, Sierra Sportsman magazine reported that in 1928, two Pyramid anglers caught eleven LCTs weighing a total of 238 pounds (an average of 21 pounds 10 ounces per fish), the largest weighing 39 pounds.

But an inevitable calamity was looming. In 1905, Derby Dam was constructed on the Truckee River, 35 miles upstream from its inlet to Pyramid Lake. The dam not only blocked the native LCT from their natal spawning grounds but also diverted half of the Truckee’s water to Lahnotan Reservoir, cutting the flow in half, and at times, entirely. Over the next three decades, Pyramid Lake’s water level dropped over 20 feet. The giant LCT were physically cut off from their prime spawning grounds—the clean gravel beds of the middle and upper Truckee River where the water flowed clear and cold.

“The native cutthroat trout of Pyramid Lake, the largest of all our trouts, reaching more than 60 pounds and representing a millennial horizon of evolutionary development, was extinguished forever by an irrigation diversion courtesy of the United States Bureau of Reclamation.”

Thomas McGuane

In 1938, federal fish biologists witnessed the Pyramid LCT’s final spawning run as the Truckee River flow was cut off. They measured 195 of the dying trout attempting to spawn and estimated them to be seven to ten years old or older, averaging thirty-six inches long and weighing 20 pounds.

Behnke noted that “The prevailing biological thinking of the time did not comprehend the significance of special adaptations at the population level. Biologists assumed that since the full cutthroat trout species was not extinct and other populations of the LCT subspecies still existed, any population of the species, and particularly of the same subspecies, could be stocked into Pyramid Lake and grow to sizes comparable to the original Pyramid Lake LCT.”

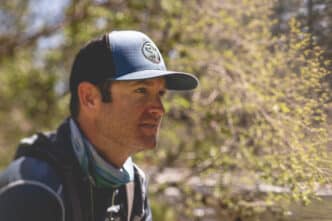

Photo by Bob Gaines

By 1944, the giant LCT was extinct in Pyramid Lake. “With one short-sighted and ill-conceived project,” wrote Ralph Cutter, “the Bureau of Reclamation destroyed the greatest freshwater trout fishery in the world.”

In the 1950s, to reestablish the recreational fishery, the Paiute tribe culled LCT from nearby lakes to cultivate a strain closest to the Pyramid Lake natives. They eventually developed the “Summit Strain,” which was predominantly from Summit Lake. They produced the strain in a hatchery and then stocked between 600,000 and one million into Pyramid Lake every year.

The Summits thrived, creating a remarkably productive recreational fishery for the Tribe who benefitted financially from selling fishing permits.

Although they didn’t spawn naturally, every spring the Summits displayed brilliant crimson spawning colors. They cruised the shallows in great schools, drawn to the tribe’s Sutcliff hatchery when freshwater was released into the lake via an artificial spawning channel. The cruising fish were easily accessible to waiting anglers, perched on ladders, and lined up in droves along the adjacent North Nets and South Nets beaches.

Rob Anderson began guiding at Pyramid Lake in 2002 as the Lake’s first non-tribal guide. He describes the prolific fishing afforded by the massive population of Summits: “Fifteen years ago it was an easy fishery. Tie on a midge and hang it under an indicator, and have a twenty fish day.”

“During the spring season at South Nets I’d have groups of fourteen anglers catch and release 500 fish in a day all the time,” Rob says. “I owned more ladders than any painter in Reno.”

But the Summits, while plentiful, never attained the gigantic sizes of the original fish, maxing out on average at 8 or 9 pounds, rarely growing over 15 pounds. “They’re pure LCT,” said Behnke, “but they lack that peculiar adaptation to feed effectively on tui chubs,” underscoring the subtle but crucial difference between native and wild trout.

Behnke noted that “millions and millions” of Summits were stocked into Pyramid over many years but “none of them reached over 20 pounds, much less 40 to 60.”

DIVINE INTERVENTION

In April 1977, Kent Summers, a biologist for the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, working with the BLM, sampled a small unnamed stream on the Utah side of the Utah/Nevada border, high above the desolate western edge of the Bonneville Salt Flats. To his surprise, he discovered LCT and reported his findings.

That summer, Don Duff, a Utah BLM fisheries biologist, and Terry Hickman, a graduate student working on his master’s thesis on Bonneville cutthroat trout, collected samples and sent them to Dr. Behnke, who just happened to be Hickman’s thesis advisor at Colorado State University.

They dubbed the stream Donner Creek since it drained into Donner Springs, the first water source for the Donner Party after they crossed the vast Bonneville Salt Flats. “I didn’t know it at the time,” said Duff, but they’d found what Behnke called “the rare cutthroat trout discovery of the century.” It would become known as the Pilot Peak strain.

Behnke conclusively identified the fish samples as Oncorhynchus clarki henshawi based on their unique spotting pattern, distinct number of gill rakers, and pyloric caeca (appendages on the intestine).

“We determined that it had been there a long time, probably before the turn of the century,” said Benke, “and at that time, the only LCT used in propagation and stocking was from Pyramid Lake.”

As if by divine intervention, the stream had natural barriers preventing hybridization from other trout, and no records could be found of any additional stocking.

The question was: Did this remnant population still retain the piscivorous fish-eating genetics of the original Pyramid Lake giants?

By pure happenstance, rancher Steve Doudy had built his remote dream house adjacent to the stream, tapping into it with a pipeline for his water source. And he just happened to have built a pond, too.

Bryce Nielson, a biologist at the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, teamed up with Doudy to start a brood stock in 1984. “Bryce came walking up with two beers and said, ‘Hey, I thought you might be thirsty,’ and we formed a relationship right then and there.”

Once in the pond, the 10-inch fish grew up to 14 pounds and 32 inches. Fathead minnows were raised to feed them, and when they tossed the minnows into the pond, the voracious trout chased them right up onto the shore.

With Nielson’s help, Doudy built two more ponds and tended to the broodstock for over 20 years. “I was just lucky to be here and take care of these fish. I take a lot of pride in it,” Doudy said.

In 1995, brood stock eggs were transferred to the Lahontan National Fish Hatchery (LNFH) in Gardnerville, Nevada.

In the early 2000s, improvements in DNA technology allowed geneticist Dr. Mary Peacock to extract DNA samples from old Pyramid Lake LCT fish mounts from 1911 to 1913 and compare them to the Pilot Peak DNA. These tests confirmed that the Pilot Peak fish were a genetic match to the original strain.

LNFH began stocking Pilot Peak LCT into Pyramid Lake in 2006. In 2007, 300,000 were stocked, identified by clipped adipose fins.

About 20 percent were outfitted with small dorsal fin ID Floy tags.

Eyebrows were raised in 2012 when a fly fisher caught and released a tagged 36-inch Pilot Peak fish that weighed 24 pounds. Stocked in 2007 at 8 inches, its growth rate was ½-inch per month.

By 2019 it was estimated that 900,000 Pilot Peak LCT resided in Pyramid Lake. In recent years, about 200,000 Pilot Peak fish have been stocked annually.

In February of 2021, fishing from a ladder on the western shoreline, fly angler Quin Pauley caught and released a 39-inch Pilot estimated to weigh 30 pounds. Then, on October 5, 2023, Klay Gustin, spin fishing from a boat near the eastern shoreline, caught and released the largest LCT seen since the 1930s: a 31-pound 4-ounce Pilot Peak fish, albeit weighed in the boat on an uncertified scale. A remarkable photo shows him hugging the giant trout, too big to hold out with extended arms for the typical exaggerated grip and grin shot.

FISHING PYRAMID LAKE TODAY

“What’s going on now is eye-opening,” says Rob Anderson. “Pyramid has gone from a numbers fishery to a trophy fishery, like fishing for steelhead.” Rob estimates the number of Summits in the lake today is only 5 percent of what it was 15 years ago. Far fewer Summits are being stocked, and they average 4 to 6 inches, smaller than before. “All of them get eaten,” says Rob. “A hatchery-raised cutthroat trout is the most vulnerable fish ever. It’s candy to cormorants, gulls, the trout, and even the larger tui chubs.” The lake’s apex predator, the voracious Pilot Peak fish, eats not only the small Summits but the stocked 10-inch Pilots as well. One harvested adult Pilot’s stomach contents included 23 Floy tags.

Rather than focusing on the spring season, Rob and his guides have shifted their operation primarily to October and June, targeting the Pilot Peak fish. “I’ve had to recreate myself,” says Rob. “What we’re doing now doesn’t resemble what we were doing 15 or 20 years ago. If you really want to catch that fish of a lifetime at Pyramid, early October and June are now the best months. It’s warm, there’s nobody there, and we pretty much have the lake to ourselves.”

Rob explains how the first week or two of the season presents a unique opportunity: “Tui chubs, the big trout’s main food source, can handle warmer water with less oxygen. They spend the entire summer in the top five feet of the water column, hiding from the trout. So, when the lake opens on October 1 usually these minnows are near shore and the surface. We go out and find the bait balls.”

Fish-finding sonar and fishing from boats, pontoon boats, kayaks, and float tubes are key. Fishing from an anchored position with a full sinking line, either stripping or vertically jigging with heavily weighted baitfish patterns (like Rob’s Tui Chewey), is also key. The fish are usually suspended between 20 and 60 feet.

By late October the water cools down and the minnows head for deeper water, as do the trout. Slow fishing is the norm until about mid-November, when the trout begin prowling the shallows again. “Mid-November to mid-December is a fantastic time to fish from shore,” says Anderson, typically off a ladder to get out of the chilly water and access deeper water and drop-offs.

Two tried and true shore fishing techniques are: Hanging one or two nymphs under an indicator with floating line at a drop-off, or stripping one or two flies with a sinking line in the shallows (10 feet deep or less) off one of the lake’s beaches.

The classic Pyramid stripping set-up is to use a 7- or 8-weight rod, a full sinking line with a shooting head that sinks at least 5 inches per second, and a 7-foot leader with Doug Oulette’s foam Popcorn Beetle or Andy Burk’s foam Loco Tadpole (in size 6) tied on a dropper or tag at 4-feet, trailed by an unweighted black woolly bugger or woolly worm (size 4 or 6) on 3 feet of 12-pound fluorocarbon tippet.

During the winter it’s often cold enough for ice to form in your rod guides, and fishing gloves are called for. It can be tedious, with bites few and far between, but the biggest fish of the season are often caught in January from shore.

The spring season, late February through mid-April, is the most crowded time at the lake. Up to ten years ago, March was the best month to fish the lake, when thousands upon thousands of Summits would cruise the shoreline near the artificial spawning channel. These days they still do, but in ever-dwindling numbers.

It’s still the best time of year to fish nymphs under an indicator, like the Albino Wino or the Mahalo Nymph, and when you hook up,it might be a 4-pound Summit or a 20-pound Pilot. Balanced leeches and balanced baitfish patterns work well too, especially in choppy conditions.

In June, like October, it’s time again to get out in a boat or watercraft and target the Pilots, which average around 8 pounds, with full sinking lines in the deeper water. Often the deep bite is good right up to the end of the season, June 30. “It’s our favorite month to fish the lake now,” Rob says, “and there’s a good shot at that fish of a lifetime.”

Pyramid Lake | Quick Guide

Access Maps

The Pyramid Lake Beach Map found on Reno Fly Shop’s website details all the Pyramid Lake shore spots with information on access and best techniques for each.

Licenses and Permits

For Tribal fishing, boating, and camping regulations/permits visit pyramidlake.us. One-day permit is $24, two-day is $48, and three-day is $62.

Boating permit fees are $26 for one day and $66 for three days. Boating permits are not required for personal watercraft such as rafts, float tubes, kayaks, and canoes unless they have a motor attached or are occupied by more than one person.

Regulations

For information on fishing regulations (hours, closed areas [the majority of the shoreline], bag and slot limits, etc.),

visit pyramidlake.us/fishing.

Lodging

Pyramid Lake Lodge, Sutcliffe, NV

The lodge offers trailer, mobile home, and cabin rentals as well as a bar and grill and a small convenience store.

Camping

Overnight camping is allowed at the lake at all the western shoreline fishing areas. A tribal overnight camping permit costs $32 per vehicle for one day and $82 for three days.

All licenses and permits are available online at pyramidlake.us/permits.

Fly Shops

Reno Fly Shop sells Pyramid gear and can provide access information and techniques that work best at particular times of the year.

238 S. Arlington Avenue, Reno. 775-323-3474

Trout Creek Outfitters has knowledgeable staff, carries Pyramid-appropriate tackle, and has a four-part series of articles about Pyramid on their website. 10115 Donner Pass Road, Truckee, 530-563-5119

Mountain Hardware and Sports also has knowledgeable staff and fishing reports for Pyramid Lake on their website.

11320 Donner Pass Road, 530-587-4844

Guides

Rob Anderson, 775-742-1754, PyramidLakeFlyFishing.com

Mike Curtis, 775-997-3676, Buckingtrout.com

Pyramid Fly Co., 887-732-3597

Autumn Harry, KooyooePaaGuides.com