Williamson River, Oregon

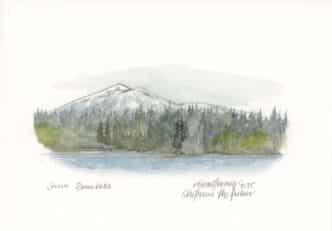

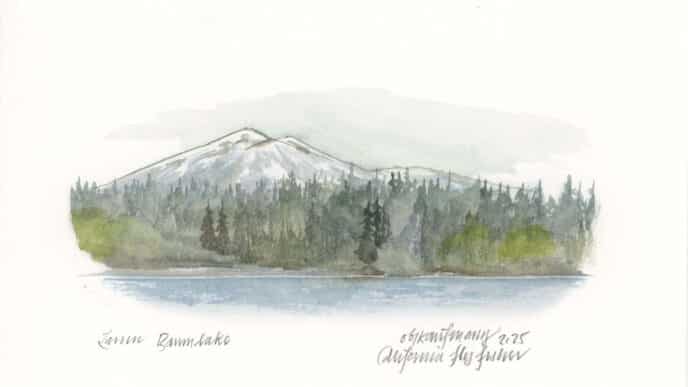

Approximately 7,700 years ago, Mount Mazama blew its top, creating modern-day Crater Lake and spewing a considerable portion of its ~8,100 foot peak all over the western U.S., laying down a deposit of ash and pumice to cover the nearby mountains and fill the valleys with hundreds of feet of debris.

Today, 35 miles southeast of Crater Lake, the scant precipitation that falls in this rain shadow area of southern Oregon percolates through these pumice layers, emerging from the numerous springs around the Yamsi Ranch to form the remarkably pure and clear headwaters of the Williamson River, the northernmost tributary to the Klamath River.

Yamsi Ranch has been and always will be a working cattle ranch, dating back to when the Hyde family first acquired the land near the turn of the century. Cattle ranching and ecosystem conservation have historically not always gone hand in hand.

Irrigation, access to water, and the grazing needs of large herds of cattle have often been at odds with environmental movements. This is changing slowly, but the acknowledgment that an ecosystem in balance is superior to one that favors one factor over another has become more prevalent lately. Just a Google search with the terms “ranching” and “conservation” gives numerous results of public and private organizations, as well as individuals promoting the benefits and success stories of bringing these groups together.

Photo by Thomas Knoble

Although they may not have realized it at the time, the Hyde family were early pioneers in viewing their land from a big-picture perspective, balancing the needs of their herd with the health of the environment. While the cattle business was what paid the bills, the early Hyde generations passed down a strong appreciation for the balance between domesticated cattle and the other animals and plants sharing their land. Early stories of the ranch are filled with angry bankers’ ire at efforts that didn’t always maximize herd yields but instead diverted money, time, and other resources to maintaining and improving the natural habitat or repairing accidental damage caused by cattle operations. Tales of raising, moving, branding, and feeding cattle are interspersed with stories of rescuing hawks, deer, elk, and sandhill crane eggs, which then hatched, imprinted, and followed the Hydes around for years like strange, 5-foot-tall ranch dogs.

More recently, the Hydes began formalizing the practice promoted by the Savoy Institute and their Holistic Management program. Although the program has several components, the most prominent is using cattle as tools to restore grasslands by grazing herds in fields for a short, intensive period before moving them on. Ideally, this rotation mimics the natural balance of these grasslands, between plant growth and the historical grazing patterns of deer and elk, leading to healthy grass and ecosystems without relying on resource-intensive or artificial techniques.

Now, as the fourth and fifth generations of Hydes grow into their roles as land stewards, the years of careful management and effort are evident throughout the Ranch, especially along the river. From the headwaters near the Ranch HQ at just under 5,000 feet in elevation, the Williamson winds clean and pure back and forth down the ranch at a consistent 42 degrees, flowing north and out the bottom of the property before turning west into the Klamath Marsh and eventually into Upper Klamath Lake, where it ultimately flows into the Klamath River. The Hydes have dedicated years carrying on their legacy of habitat improvement, adding the occasional deadfall or boulder to provide cover for fish and installing electric fences to protect the streambed from cattle. These efforts have paid off, as the nearly seven miles of river on the ranch support incredible numbers of brook trout, said to be the biggest in Oregon, along with the heralded Great Basin redband trout.

Twelve of us from the San Francisco Golden Gate Angling and Casting Club made the trip up to the ranch, northeast of Klamath Falls, in mid-August this year. Leaving early Thursday morning from the North Bay to handle the roughly six-hour drive, we arrived at Yamsi early in the afternoon, where we were greeted by Tom Hyde, his wife Leanne, and their two children. After the inevitable unburdening of vehicles into absurd piles of gear on the deck and a quick costume change, we loaded back up to take the five-mile dirt road trek to the river’s bottom for an evening of fishing.

The bottom of the river can be a little disorienting. You’re looking at a beautiful touch of river to your left, curving away to disappear around a bend. To your right, downriver and looking north, there is a bench and fence line about 200 yards away, which marks the end of the property. It’s necessary to spend some time exploring to wrap your head around the idea that between you and that bench lies a mile and a half of winding river, including bends, holes, straights, undercut banks, deadfalls, and boulders—all ridiculous fishing spots. Should you get tired of this bounty, there are roughly six-plus miles of river upstream with similar characteristics to keep you interested.

We scrambled to rig up, orient ourselves to the challenge ahead, and spread out on the meadow. As is common on most fishing trips, the first moments on the river involve some education. This includes a bit of orientation, an acknowledgment of what the river presents, a recognition of the challenge ahead, and an anticipation of the problem-solving needed for the days to come. We fumbled through different solutions until dark, then hustled back to the ranch for a home-cooked meal served by the Hydes in the iconic building that is the ranch headquarters.

Sitting in the old ranch house, post gut-busting dinner, beverages topped off, we got serious. After all, between the bunch of us, there had to be a decent fisherman somewhere. With another round of libations, some shared tips, tricks, and gear adjustments, we formulated a plan. The strategy included getting up with the Hydes, breakfast, swilling plenty of coffee to shake off the night’s excesses, and heading back down to the bottom of the property to dig in.

During the planning stages, we had hoped to time our trip to the end of the hopper season, a special time of year after the early bugs and Hex hatch, but before the late-season October caddis and mahogany duns. When the hopper activity is on, the Williamson shifts into an absurd cast-one, catch-one mode, like a goofy video game. However, the timing of the hopper season depends on water levels, air temperature, and the number of cold days peppering the summer months.

The short story is we missed it. A healthy winter and plentiful early-season sunshine have been a boon to the grasses and plant life, ideally creating perfect conditions for hoppers. However, this year the high grass in the river channel further downriver has actually impeded the flow, causing water to back up and flood the fields as much as knee deep. Bad news for hoppers, great news for fish who were no longer limited to their customary holes and hiding spots and could feed on the plentiful food sources. High water doesn’t mean faster water, and besides making a walk across the meadow more aerobic than before, it might have improved the fishing since the fish are now everywhere in the river.

Motivated by the previous night’s heroics and an incredible breakfast served up by the Hydes, we dove into the bottom of the ranch mid-morning. Understanding that hoppers weren’t the premium, we expanded our options to anything in the fly box.

As it turns out, everything worked. Over the next three days, hoppers worked. In many flavors. PMDs worked. Elk hair caddis worked when there wasn’t a caddis within three counties. Scuds dredged through a pool worked. A small leech with a slow retrieve worked. Want to throw a chubby with the ugliest dropper in your flybox? That would work. A Parachute Adams in sizes 16, 18, or 20 with a dark belly? Works. My floating black ant didn’t float so well, but still worked. I don’t know if anyone in our group got around to throwing beetles, bees, or mouse patterns, but I suspect they would have worked, too. Russ swore by his Turk’s Tarantula pattern. Alan spent three days throwing hoppers in multiple patterns and never failed to produce. Mike and I beat up the “Sucker Hole” with everything in our fly box. It’s unclear if the hole is named for the dumb fish or the returning fisherman, but Mike pulled at least six of the most stubborn surface-feeding fish out of that hole.

The Williamson this year has an incredible number of hungry fish per mile. Since the river runs back and across the meadow, there’s plenty of opportunity to connect with your trip mates. If you prefer to fish solo, with nobody around in a beautiful setting, catching fish and enjoying the Williamson at your leisure, there are miles of river to explore. If you want to fish shoulder to shoulder with your buddies, to celebrate their catches, and laugh at their misses, that’s available too. Mostly, we chose the latter, with the associated adjustments in vocabulary appropriate for the occasion and an occasional nip from the flask. The only other constant during our trip was Chef Leanne Hyde’s efforts to fatten us up regularly for what must be some future culling or impending apocalypse.

Not to imply that the Williamson is an easy fishing river, but in fact, it’s incredibly technical. While the fish don’t seem to be terribly concerned with actual fly colors or maybe size, fly behavior and action are critical. The Upper Williamson is gin clear and slow-moving, so sneaking up on holes is advantageous. Several times, I crept up to a hole thinking I was in a perfect position, only to watch 15 fish scatter before me as my head cleared the grass, revealing the absurdity of my approach. Long, gentle presentations and long drifts are the norm. The almost universal mantra that a “drag-free drift” as the pinnacle of fly dry fly fishing holds true. Except when it doesn’t. A dry fly presented cleanly on top might not get a bite, but what we started to call the “Yamsi Twitch”—a clean presentation and drift, followed by a slight pull or shake of the rod to give the fly a little action like a dying bug, followed by a quick retrieve would often result in an aggressive strike somewhere in there where a straight drift yielded no results.

It took us a while to understand the big picture. All of us experienced some period of no activity, which was inevitably followed by an abundance of hungry fish. Over the next few days, as Leanne overserved us with incredible calories during the meals, guidance from Tom Hyde and his son Caden, a bit of trial and error, and a few facepalm-worthy moments of stupidity, we reached a point where we could understand parts of the Williamson and the amazing fish that live there.

I know Jeff won the ugly fly contest and took a bit of our money. But in the end, I’m not sure how many big brookies I caught, along with some of those beautiful rainbows. I don’t know how many fish our group caught, but judging by the number and frequency of yelps across the meadow, I can only guess. I don’t know who caught the biggest fish, although Adam seemed to have a run-in with an 18-inch brookie, and Patrick documented his 21-inch rainbow with a picture. I don’t know how many fish were caught on dries, or on leeches, or hoppers, or nymphs. I’m not sure who caught the first fish. Or the last. But I didn’t hear a bad fishing report from anyone, whether they were fishing solo or with the peanut gallery. I do know that everyone in the group wants to be on the short list to return next year. I’m not surprised, but that’s gotta count for something.