All mining practices, with the possible exception of gold panning, are intrinsically destructive, because natural resources must be damaged or destroyed in order to gain access to and extract the sought-after substance, be it gold, silver, coal, aluminum, copper, or another mineral having real or perceived value. That’s simply a statement of fact. No judgment — good, bad, indifferent — or opinion is intended by it.

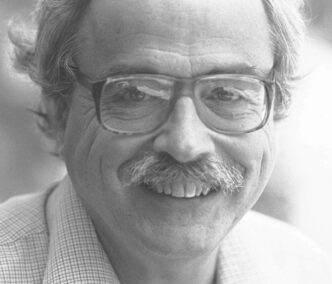

Suction dredge mining is a form of mining that occurs almost exclusively within streambeds. The following abbreviated summary of how suction dredge mining is carried out in California streams is based on my personal observations over many years, as well as on my research on the subject in connection with my participation in the process for the enacting of new suction dredge mining regulations conducted by the California Department of Fish and Game (now the Department of Fish and Wildlife, the DFW). I am not a scientist, but I am a concerned angler with extensive stream-based experience in the Sierra foothills, where this practice has occurred. Although my goal here is to be objective and balanced, anything in this article that could be construed as an opinion is just that — my personal opinion, albeit based on experience and research.

Suction Dredge Mining

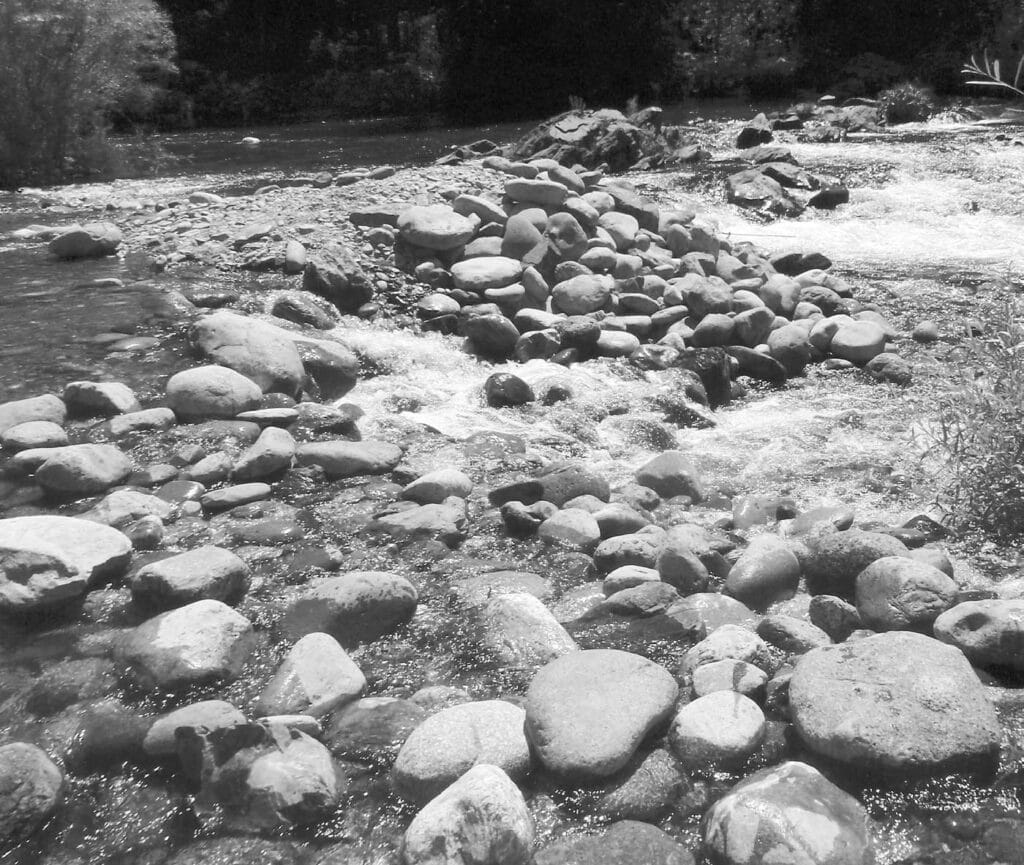

The suction dredgers’ preferred venues, at least in the Sierra foothills, where I live and fish, tend to be canyon streams, because during high flows, the canyon streams carry gold from the upper reaches of a watershed downstream, where it is deposited in the substrate as the flows slow and spread out. The mining apparatus consists of a pontoon or other floatation device that is tethered to a streamside object such as a spike, tree, or rock. A gasoline motor and a powerful water pump (sometimes more than one pump and motor, if the floatation device is large enough) are mounted on the floatation device. There is a long, flexible hose attached to the intake port of the pump. This hose, which is normally about four inches in diameter, but can be much wider, is used to vacuum substrate from the stream bottom. The hose is manipulated by the dredge operator, who usually wears a snorkel and mask while moving the hose end along the bottom. The pump’s discharge port (which may or may not have an attached hose) causes pump effluent to dump into a sluice. Heavy material drops into the sluice’s slots or traps and remains there. The water, which contains suspended silt and other debris, exits the sluice and discharges into the stream below the dredge. The dredger’s objective is to get to or near the bedrock beneath the substrate, because apparently, that is where gold, if it is present, will most likely be located, due to its weight. Often it becomes necessary to remove larger cobble from the streambed in order to get to the smaller substrate. This is done manually where feasible, or, when necessary, with hand or motorized winches that are normally attached to trees, and with other tools. The result is that larger cobble that is normally wholly or partially submerged is removed from the water and piled streamside. As such, it no longer serves as a refuge for fish and other aquatic life, such as benthic macroinvertebrates (BMIs) — the aquatic insects on which fish feed.

Silt that is discharged from the dredge is transported downstream over distances that vary with the characteristics of individual rivers. Governing factors include stream gradient and flow velocity, stream geomorphology, and flow volume.

(There are other variables, but these appear to be the most salient factors.) Where significant, prolonged dredging has occurred, downstream areas often become clogged with silt.

Suspended silt consists of more than soil and detritus. Because canyon streams (such as the drainages of the upper American River) were heavily mined during the Gold Rush days, their substrate contains significant amounts of elemental inert mercury, which was used by early miners to separate gold from ore and other minerals. Although it is no longer used for this purpose, mercury is a heavy metal (as is gold) and remains near the bottom of the substrate as an inert element found usually in globules. Anyone who has broken a thermometer or other instrument that contains mercury can visualize this. When it is sucked up into the dredge pump, some of the inert mercury globules are broken down into small flecks or droplets that move downstream from the dredge, along with the silt. Scientists have established that when this occurs, these formerly inert particles become reactive with ultraviolet light and oxygen. The scientific term for this is the “methylization” of mercury. Whereas it was inert when undisturbed in the substrate, when methylization takes place, mercury becomes available in the water column to fish and BMIs in a highly toxic form, resulting in mercury poisoning. Of necessity, this summary, although accurate, leaves out more than it includes. Readers desiring confirmation or more information should consult the literature on this subject by executing an online search for the science involved.

Suction Dredge Mining and Regulation in California

According to the DFW, small-scale suction dredge mining activity in California began in the 1960s and peaked during the high gold prices that prevailed in the late 1970s and early 1980s. During the 1980s, the Fish and Game Code was amended to include regulatory measures for this practice. What was then the DFG issued its initial regulations to implement the code amendments in 1994, after certification of an environmental impact report (EIR). Amendments to the regulations were proposed in 1997, and a draft subsequent EIR (SEIR) was prepared. This completed. Early in the 2000 decade, the Karuk Indian tribe instituted litigation against the DFG, alleging (among other things) that suction dredge mining is deleterious to endangered anadromous fish species in the Klamath River and other Northern California streams. In 2006, a court order was issued in this litigation requiring the DFG to institute a process to amend its regulations and to engage in an appropriate environmental review process to support proposed regulatory changes. After consulting with interested parties, the DFG notified the court that it would need to undertake an extensive environmental review, and in 2009, the court issued another order prohibiting the DFG from issuing suction dredge mining permits while the litigation was pending or until further court orders were issued. In a separate action, on August 6, 2009, Governor Schwarzenegger signed AB 670 into law, prohibiting (with a few minor exceptions) all suction dredge mining until the court-ordered process can be completed. This moratorium commenced immediately upon signature of the bill by the governor.

Subsequently, also in 2009, the DFG commenced the court-ordered process by drafting proposed new regulations and the new SEIR required to support any new regulations. A draft of those documents was issued in February 2011. Between March and May of 2011, the DFG held a series of public meetings throughout the state to receive input from all interest groups. Along with several friends, I attended one of those meetings in Sacramento and submitted oral testimony regarding the revised regulations and the draft SEIR. There were at most five persons from the environmental community at that meeting; there were over three hundred individuals from the suction dredge mining community.

The official comment period on the draft SEIR ended on May 10, 2011. On my own behalf and on behalf of a group called the Foothills Angler Coalition, I submitted lengthy and detailed written comments to the DFG on both the draft revised regulations and the draft SEIR. Many other organizations also filed extensive comments. The vast majority of the filed comments were from environmental and related groups, pointing out a litany of legal, scientific, and practical flaws in the regulations and in the draft SEIR.

The DFG’s schedule called for release of the final regulations and final SEIR during late fall of 2011 — which meant that the regulations would become final sometime before the end of that year and that the DFG would then resume issuance of dredging permits. However, on July 26, 2011, Assembly Bill 120 was signed by Governor Brown. This legislation extended the moratorium through June 30, 2016. AB 120, in addition to extending the moratorium, imposed several new stringent requirements that the DFG and now the DFW must meet in conducting the required environmental review and issuing new regulations. First, it requires that any “new regulations fully mitigate all identified significant environmental impacts.” This “fully mitigate” requirement increases the mitigation requirements embodied in the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Under CEQA, when mitigation measures are deemed impractical or not feasible, or for other reasons, adverse im-pacts (even though severe) can be “overridden,” and the project (in this case, the revised regulations) will be allowed to proceed. The “fully mitigate” language appears to close that avenue — that is, identified significant adverse impacts must be fully mitigated, in default of which the revised regulations cannot be adopted or implemented, and the moratorium would remain in effect, subject to its 2016 sunset date.

Second, AB 120 requires that the department implement “a fee structure . . . that will fully recover all costs to the department related to the administration of the program.”The fee structure for the department’s permitting program is prescribed by statute — Fish and Game Code section 5653. The current fee structure is woefully inadequate for covering administrative costs, which of course include monitoring and enforcement. The department claims that changes to the fee structure are beyond its authority and will require action by the California legislature and approval by the governor. Perhaps that is the case, but it still remains incumbent on what is now the DFW to draft and publicly vet a proposed fee structure. Absent satisfaction of the statutory fee condition, suction dredge mining cannot resume.

According to the DFW, the moratorium established by SB 670 and AB 120 does not prohibit or restrict nonmotorized recreational mining activities, including panning for gold. It also does not prohibit or restrict some other forms of mining, including, for example, practices known as “high banking,” “power sluicing,” “sniping,” or using a gravity dredge, as long as gravel and earthen materials are not vacuumed with a motorized system from the river or stream.

Nonetheless, other environmental laws do restrict those same mining practices. For example, Fish and Game Code section 5650 prohibits the placement of materials deleterious to fish, including sand and gravel from outside of the current water level, into the river or stream. Further, Fish and Game Code section 1602 requires that any person “notify” the DFW before substantially diverting or obstructing the natural flow of or substantially changing or using any material from the bed, channel, or bank of any river, stream, or lake. (It’s not clear, however, what the DFW would do in the case of “notification.”) Information on these issues is available at 1600. Additionally, the State Water Resources Control Board has authority over the protection of water quality and has recently provided information and guidance regarding “high banking.” Information on this issue is available at http://www.swrcb.ca.gov/water_issues/programs/cwa401/suction_dredge.shtml. The draft SEIR, along with other information on the regulatory approval process, can be found at http://www.dfg.ca.gov/suctiondredge.

This website contains all of the DFW’s updates. Most recently, as part of the state’s 2012 budgetary process, a trailer bill (SB 1018, signed by Governor Brown on June 28, 2012) was passed that removed the 2016 sunset date for the moratorium on dredging and reaffirmed the substantive requirements of AB 120. This is significant, because as it now stands, unless and until the DFW meets the strict standards imposed by AB 120 and the trailer bill — no matter how long it takes — no suction dredging permits can be issued. The DFW is required to submit a comprehensive report to the legislature in March of 2013 describing the status of the process and detailing its progress in resolving the environmental issues. The DFW has indicated that it intends to meet that deadline (the report may be available as you read these words). This report will be the next major development in the suction dredging wars on the legislative front.

Meanwhile, multiple lawsuits against the DFG/DFW, from all sides of this controversy, were filed in various locations throughout the state. All of them were consolidated into one proceeding in the Alameda County Superior Court. Surprisingly, in a subsequent maneuver, the department joined forces with the mining community in making a joint request to the California Judicial Council to move all of the cases to San Bernardino County. That request was granted, and the cases are now all pending in that court. This litigation morass is highly complex and far beyond the scope of this article.

One more legal note: In a very recent decision, the federal Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals settled the long-debated issue of whether mining claims issued pursuant to the old federal mining statute (the 1872 Mining Law) are subject to the strictures of the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) by holding that the ESA does indeed trump the old mining law and that federal agencies administering the ESA have jurisdiction to restrict such claims.

Issues: The Draft SEIR and the Suction Dredge Mining Permitting Process

The litany of issues raised by the draft SEIR issued by the DFG in February 2011 is far too lengthy to cover in this article. The following is a summary of five salient points made during the 2011 comment period on the draft SEIR by those of us concerned with the impacts of suction dredge mining on the streams of the Sierra foothills. The issues are somewhat different from the perspective of the Karuk tribe and the other interested parties participating in the process on behalf of Northern California rivers such as the Klamath. I cannot speak for those parties, much less parse the issues that affect their interests.

First, we object that what was then the DFG used an inappropriate analytical approach to impact analysis. Briefly, the CEQA process contemplates identification of impacts that are “adverse” and requires an analysis of the severity of each adverse impact — that is, whether an adverse impact is severe enough to be termed “significant” and specification of feasible measures to mitigate each significant adverse impact to the point where it is “less than significant,” if possible. If that is not possible, the lead agency with jurisdiction over the project must produce and adopt a “statement of overriding considerations,” which is generally a statement that despite the severity of the impacts, there are valid policy reasons for allowing the project to go forward.

The draft SEIR, instead of analyzing each stream where suction dredging is allowed, measures impact severity on a “statewide basis.” In other words, notwithstanding the severity of adverse dredging impacts to, say, the North Fork of the Middle Fork of the American River, as long as the total statewide impact of suction dredging on all affected streams is “less than significant,” it is not necessary to specify mitigation measures for that or any other particular stream.

Our comments take the position that the methodology used by the DFG/DFW is inappropriate and legally impermissible — that there is no basis for allowing the “trashing” of individual streams just because the department perceives the overall statewide impact to be insignificant. The enactment of AB 120 added considerable support to our position by requiring full mitigation of all adverse impacts.

Second, we claim that the draft SEIR did not take into account the reasonably foreseeable effects of a planned reintroduction of anadromous salmonids to the American River above Folsom Lake. In addressing its obligations under the federal Endangered Species Act, the National Marine Fisheries Service adopted a Biological Opinion and Recovery Plan for anadromous salmonids (including chinook salmon and Central Valley steelhead) that called for reintroduction of those species into the North and Middle Forks of the American River above Folsom Dam, commencing in January 2012. The department did not take the latter document into consideration in developing the draft SEIR — that is, the it did not analyze the question of whether suction dredging would cause adverse impacts to the reintroduced salmon and steelhead, which are listed as endangered species. Our position is that the analysis is required because it is a foreseeable and important part of the impact of suction dredging on implementation of the Biological Opinion and Recovery Plan.

Third, we point out that the department did not address the potential adverse impacts of allowing the transfer of permits from individuals to organizations such as mining clubs and related entities. In the 10 years preceding the issuance of the initial moratorium, a practice developed whereby the owner of an individual claim on a river would transfer that claim to an entity with a much larger constituency, such as a mining club. Once the transfer became effective, the number of dredges on the claim multiplied geometrically. I personally witnessed this change on several rivers, including the North Fork of the Yuba River near Downieville. With the proliferation of dredges, the adverse effects on fish, BMIs, and the geomorphology of affected river segments also multiplied geometrically. When confronted with this issue, the department claimed that it had no authority to regulate those transfers and refused to take any action. The draft SEIR does not take this issue into account, and our position is that it must do so.

Fourth, we point out that the department did not address the potential adverse effects of allowing dredging in designated Wild and Scenic Rivers, including the North Fork of the American River. Dredging has in the past been allowed on rivers that have been designated as protected under federal and/or state Wild and Scenic Rivers acts. The North Fork of the American River is one such river. The draft SEIR contains no analysis of whether dredging adversely affects the protected values that gave rise to the designation. Our position is that such an analysis is required. I presented this issue, along with a host of other issues, to the Placer County Fish and Game Commission for their review and recommendations. As a result, the commission recommended to the Placer County Board of Supervisors that the board issue a comment letter to what was then the DFG opposing the proposed regulations and draft SEIR. The board of supervisors took that action, and the letter is on file as part of the record in the department’s proceedings.

Finally, we note that the draft SEIR did not address the beneficial results of the moratorium on the fisheries affected by suction dredging. During the two years following the August 2009 moratorium on dredging, I witnessed a dramatic increase in the health and numbers of trout in streams that had been damaged by previous dredging. One of those streams was the North Fork of the Yuba River. Fish had returned to areas in that stream where their numbers and size had spiraled downward in the 10 previous years as the number and size of dredges increased. I reported this observed phenomenon to the DFG before they commenced the process of drafting new regulations and developing the draft SEIR. Yet the draft SEIR did not mention it, much less conduct any analysis of the cause-and-effect connection or whether it is an indication of the nature and extent of damage that can be caused by dredging.

Prognosis

What does the future hold for the regulation of suction dredge mining on California streams by the DFW? As it now stands, from the legislative viewpoint, each and every statutory mandate imposed by the three moratorium bills mentioned above must be satisfied before the DFW can issue a single dredging permit. Superimposed on that set of strictures is the vastly complex litigation that has fallen onto the shoulders of the San Bernardino County Superior Court. I clearly do not possess the expertise to venture prognostications as to where or how this complicated process will end up. All I know is that at least for the long-foreseeable future, it appears that my beloved Sierra foothill canyon streams will be free from suction dredging. Long live the fragile symbiosis between trout, BMIs, and the habitat that they so desperately need!