It was while fishing from my float tube on Tioga Lake that I first heard of Gaylor Lake in nearby Yosemite National Park. As it turned out, the differences in fly fishing the two lakes could not have been starker.

While casting to a pod of hatchery rainbows gathered at the base of the dam at Tioga — not fly fishing at its finest — I watched a fly fisher wading the shoreline and casting parallel to it. Every so often, he would have a hookup and bring in a small trout. When I asked him what kind, he replied, “brookies.” He volunteered that he had caught some really fat and beautiful brook trout the day before at Gaylor Lake, which he said was an easy hike of about a mile and “well worth it.” After many hours of often unsatisfying fly fishing for hatchery-reared rainbows in roadside lakes, putting on my hiking boots and giving Gaylor a visit seemed exactly right.

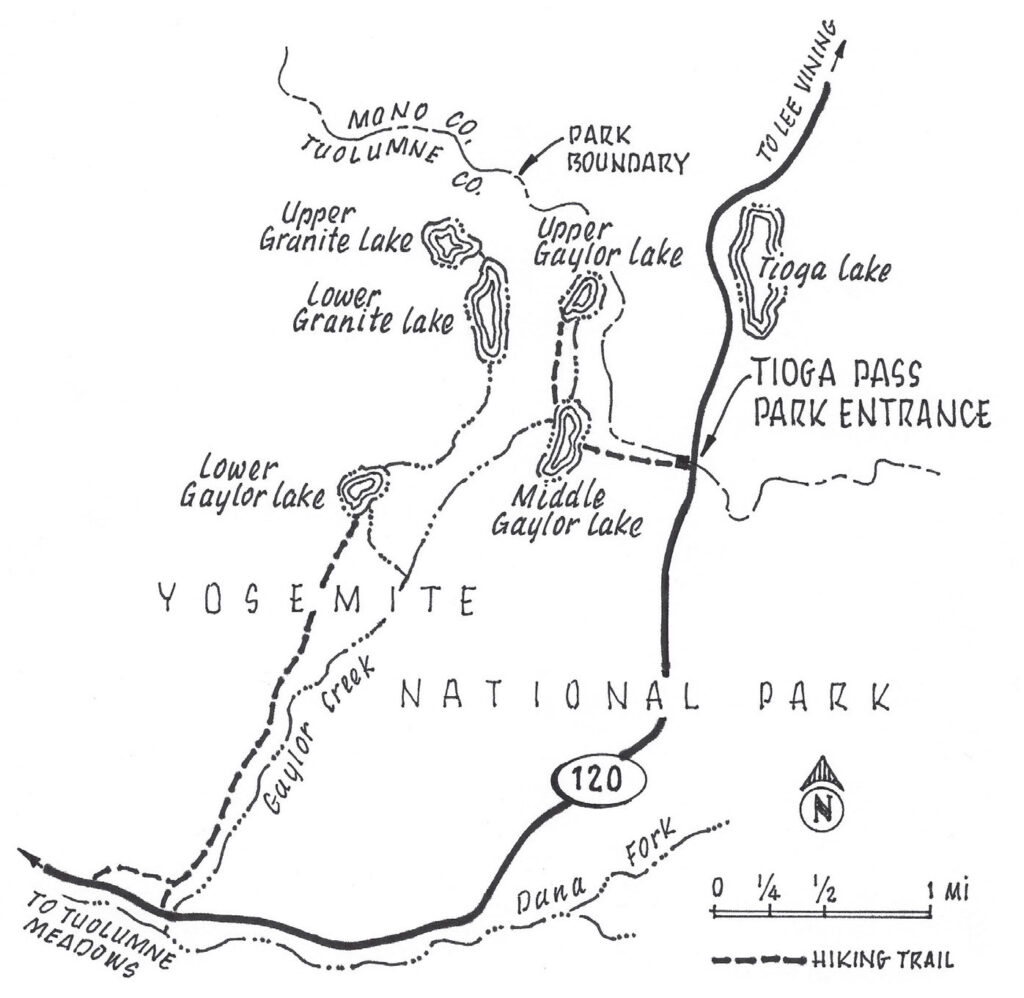

The start of the trail to Gaylor is at the parking area right next to the Tioga Entrance Station. The mainly uphill hike wasn’t “easy.” And being above 10,000 feet for much of the way tested my lung capacity and stamina.

The steep part ends when you come to a ridge. Down from it sits Gaylor Lake, actually Middle Gaylor Lake. It is an unadorned high-alpine lake in a meadowlike basin, with distant vistas of granite peaks. Within minutes, I was casting out onto the blue water. Taking in this wilderness setting while taking in deep breaths of the purest of air, knowing that wild trout occupied the water in front of me and not another person was in sight, was as uplifting and cathartic an activity as I had enjoyed in a long time.

Right off the bat, two or three trout shot to the surface as though to take my Elk Hair Caddis, only to swerve away and shoot back down into the deep. These fish obviously were not your typical easy-to-catch brookies, kicking the quality of the experience up a notch. One finally ate the fly, and I landed a stubborn 11-inch brookie, richly colored and plump.

The wind picked up and was blowing toward what resembled a small cove near where I fished. I switched to a small black Woolly Bugger, cast to the roily water lapping against the shore and stripped back. Over the next 20 minutes, I hooked four fish, all sizeable for brookies.

(As a side note, Steve Beck, in his excellent book, Yosemite Trout Fishing Guide, recommends using small fly patterns when fishing these high-elevation lakes, including midge and caddis imitations, since the food sources are mainly tiny. But he also mentions that the often frequent winds can sometimes make seeing a fly impossible, and bright attractor patterns then become the fly of choice.)

Middle Gaylor is just one of a cluster of lakes in this immediate vicinity, all holding brook trout. They were first planted in these lakes (and other park waters) before the turn of the nineteenth century. Rainbow trout were also planted in Yosemite’s lakes, but as is often the case, brook trout outcompete them, and the rainbows disappear from lakes where the two species were planted together. Additionally, the brook trout is one of the few species that can spawn solely in a lake without a feeder stream (rainbows cannot), so brookies have taken over many alpine lakes.

From Middle Gaylor Lake, one can continue on the trail along the east side where the feeder stream comes in. It continues to Upper Gaylor Lake, reachable in about 20 minutes of hiking.

The other Gaylor lake, Lower Gaylor, can be accessed by hiking cross-country from Middle Gaylor — a distance of approximately one mile — or by taking the trail to it from the Tuolumne Meadows Lodge on Highway 120.

The brook trout in these lakes can reach the one-foot mark, perhaps even bigger. Due to its proximity to the road, Middle Gaylor gets the most anglers, so the fishing may be less productive than at either Lower or Upper Gaylor, but it is still good, as I discovered.

Two other less-visited, nearby lakes with brook trout are Upper Granite and Lower Granite.

If one wished to visit all five lakes in one long day — a total distance of approximately 5.7 miles — the route could look like this. You start with the one-mile hike to Middle Gaylor, as described above. At the inlet stream, the trail continues up to Upper Gaylor, where farther up are old mining ruins from a town once called Dana. From Upper Gaylor, you can turn west and walk cross-country, that is, with no trail, across a ridge and down to the easily found Upper Granite and Lower Granite lakes, “blue gems backed by steep granite heights,” as described in one hiking guide. You can then curve southward to reach Lower Gaylor Lake. Finally, you can hike cross-country back to Middle Gaylor Lake, where you can then retrace your steps, now mostly downhill, back to the parking area.

Yosemite Lakes

Although Gaylor and Granite Lakes are definitely worth a trip, especially given their feasibility as a day hike, Yosemite National Park offers more outstanding fishing opportunities than I’m sure most fly fishers realize, as I didn’t before researching this article. In fact, if I were a few years younger, I would devote a lot of time and effort to visiting its waters, not only because the fishing appears very promising, but because there’s a whole lot more to being in Yosemite.

When you hike in Yosemite, you will likely trod through old-growth forests and across glacier-sculpted granite, with possible sights of scintillating waterfalls, vistas of majestic domes and peaks, and in the presence of wildlife in all its myriad forms. This is Yosemite, after all — one of the most beautiful places on the planet. Trekking to a lake that harbors the most resilient of creatures — wild trout — is just another good excuse to be there.

Yosemite has roughly two hundred and fifty lakes that hold trout ranging across a variety of species and sizes, including large, hefty fish. The vast majority of these waters may require a strenuous hike, but this physical element can be a way to stay young, at least in spirit and conditioning, even with accumulating years. How so many lakes came to hold trout, and several species at that, is a story unto itself. Originally, the only native fish were rainbows that entered local streams mainly from the Merced and Tuolumne Rivers. Due to natural impediments, they weren’t able to continue their journey past 4,000 feet in elevation.

Private citizens began planting fish in area waters as early as the 1870s. After Yosemite became a national park in 1890, park managers decided early on that visitors should be able to fish in the park for added recreation. Angling for fish planted in backcountry lakes, as well as in more convenient waters, provided a good reason to take a hike, encouraging more people to use the park’s ample resources.

To carry out this agenda, the Wawona Hotel Company built a hatchery at Wawona, in the southern part of the park, in 1895. A second hatchery was built at Happy Isles and began operations in 1927. But efforts to make this latter site permanent were unsuccessful, and all hatchery operations were moved to Wawona. This hatchery, however, had difficulty maintaining trout over the summer, primarily because the nearby source creek, Big Creek, got too warm. A prolonged drought starting in 1914, combined with campers degrading Big Creek, ultimately led to the shutting down of Wawona Hatchery in 1928.

But active stocking of trout in Yosemite, mainly by the California Department of Fish and Game, continued. Across the decades, the following species were planted in park waters: rainbow, brown, eastern brook, and cutthroat trout (both Paiute and Lahontan), arctic grayling, and golden trout. Selection criteria were based on whatever hatchery fish were obtainable, and they were planted into whichever lakes were accessible. With little available data to inform such randomized plantings, the successful continuance of any given species was a hit-or-miss proposition — mainly, there were misses. The most adaptable species turned out to be eastern brook trout, as was true all across the Sierra Nevada.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that park managers began to question seriously the wisdom of planting fish in waters that never held them before. What they came to realize was that indiscriminate stocking of fish could do more harm than good.

Trout were planted in many nutrient-poor lakes incapable of sustaining populations of healthy fish, so they were restocked again and again, which caused these waters to be overpopulated with stunted fish. Repeated stocking of productive lakes hampered trout populations capable of sustaining themselves if left alone. And the introduced fish were altering the ecology in significant ways, including the demise of native organisms.

Another unintended consequence of stocking was that fishing quickly became a put-and-take activity. Fishing popularity led to humans degrading lakes with beaten-down trails around them littered with garbage and other human discards.

In the 1960s, as part of a national commitment to the natural environment, the National Park Service established that priority would be given to the original mandate for national parks: “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wildlife therein, and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

This overall mandate meant the protection and restoration of natural landscapes, flora, and fauna and the elimination or diminution of introduced elements, such as nonnative fish. Fish planting in the park’s waters was scaled back, beginning in the 1970s, and planting was finally halted for good in 1990. By then, over 33 million fish had been planted in Yosemite’s waters. What fish remain in any water now are there because they survived and became self-sustaining populations — that is, “wild.”

Besides benefiting the ecology, the cessation of fish stocking meant fewer visitors coming to fish. Those who did so came more for a wilderness experience while hooking resilient, wild fish.

The aftermath of this history of stocking trout is that today, Yosemite lakes are populated with varied fish species. The eastern brook trout is the most pervasive fish, including trophy-size specimens (for a brookie) reaching 16 inches. (Upper Young Lake, Lukens Lake, Lower Cathedral, and both Upper and Lower Sunrise Lakes are good choices here.)

Rainbows, also capable of above-average size, are rarely the only species in a lake. More likely they coexist with browns. (Lakes that hold rainbows include Merced Lake, May Lake, Tenaya Lake, Dorothy Lake, Kibbie Lake, Smedberg Lake, Ostrander Lake, Upper McCabe Lake, and Eleanor Lake, among others. Catch and release is strongly recommended with rainbows.)

Adair Lake holds just golden trout. (Catch and release is strongly recommended.)

Golden-rainbow hybrids can be found in several lakes. (Tilden Lake is one.)

Hanging Basket Lake is the only one holding Lahontan cutthroats. (Catch and release is strongly recommended.)

With the possible exception of some rainbow strains, none of these fish is native to Yosemite. But, in contrast to cultivated hatchery specimens, which behave as if they are still in a cement runway with a regular feeding schedule of pellets, these trout are all superbly wild — born in these waters, consuming what nature provides, and the toughest of survivors.

To partake of this marvelous fishery, all it takes is to study a map, put on hiking boots, maybe a pack, ask questions of the Yosemite staff, and strike out on a trail. A good source on fishing prospects in all of Yosemite is the aforementioned Yosemite Trout Fishing Guide, by Steve Beck.

The angler should note that although fishing regulations for Yosemite follow the state regulations, there are differences. Fly fishers in particular might want to know that in Yosemite Valley and El Portal (Happy Isles to Foresta Bridge), only artificial lures or flies with barbless hooks may be used, and the same is true for the Tuolumne River from the O’Shaughnessy Dam downstream to the Early Intake Diversion Dam. Mirror Lake, by the way, is considered a stream and is only open during stream-fishing season (lakes are otherwise open year round).

Fortunately for the avid seeker of wild trout, Yosemite has finally gotten its act together. With the elimination of stocking and with better fish management based on good science, the park today has numerous lakes that offer superb fly fishing, including casting to big brook or rainbow trout, as well as goldens and Lahontan cutthroats. If that’s not enough, a grander place to pursue this activity does not exist.

Yosemite Fish and Yellow-Legged Frogs

Yosemite National Park is front and center for issues regarding the decline of native organisms, most especially the yellow-legged frog. Since the planting of hatchery fish in the park ended in 1990, the issue now is what to do about the pervasive presence of brook trout in Yosemite’s waters and their negative impact on the park’s ecology. I asked Rob Grasso, Yosemite’s Park aquatic ecologist, to address this issue. His response follows.

“To achieve the objective of restoring yellow-legged frogs to their historical habitat, the park is removing trout from about 10 percent of lakes with fish over a multiyear period. A lake site is considered only if a population of yellow-legged frogs can be successfully restored to it. The lake must be high-quality frog habitat and feasible for eliminating fish. The park does not use any chemical means, such as rotenone, to remove trout. Only physical means, such as gillnetting and electrofishing, are employed.

“As we know from many examples in nature, there is rarely one overwhelming factor that leads to the demise of a species. There are usually multiple contributing factors. For the decline of the yellow-legged frog, it’s been a one-two punch. Fish introductions reduced frog abundance and isolated frog populations. Then a pathogen entered that can drive a population to extinction — something that is actually rare in nature — and now you have frogs that cannot recover because they have been reduced to even smaller populations and cannot expand into historically occupied areas because fish continue to be a barrier to migration, mostly in streams. “The history of this work is one of the best examples in science that I know where anecdotal evidence that started with observations between frogs and fish from studies in the early 1900s (that is, where you have fish = no frogs, and where you have frogs = no fish) is so determinative. Next, leading researcher Roland Knapp surveyed thousands of sites, and he built a dataset that supports this correlation: where you have fish, you don’t have frogs. The obvious question is what happens if the stressor (fish) is removed — do the frogs come back? The answer is overwhelmingly yes. As we have seen, frogs not only came back after fish removal, populations exploded. However, at the same time, the amphibian chytrid disease was spreading across the Sierra, and there were simply not enough large populations of frogs to withstand this new disease. The amphibian fungus usually gets the blame for the decline of the yellow-legged frog over fish, but this is a misconception. It was simply the nail in the coffin.

“Lastly, a word about fish species and angling. Because rainbows are native to the park, at least in lower elevations with waters connected to the Merced and Tuolumne rivers, we choose not to select lakes for fish removal when those fish are rainbows. Even though many hatchery rainbows were planted, some strains may be connected to the native fish, and we want to preserve those rainbows when possible. And although we seek a balance between ecological and recreational values, since we are eliminating fish from only 10 percent of the park’s lakes, the weight here favors the angler, who is able to come here and fish for these wild trout in the grandest of settings.”

— Bob Madgic