GEOLOGY: LONG VALLEY CALDERA

By Jeff Ludlow

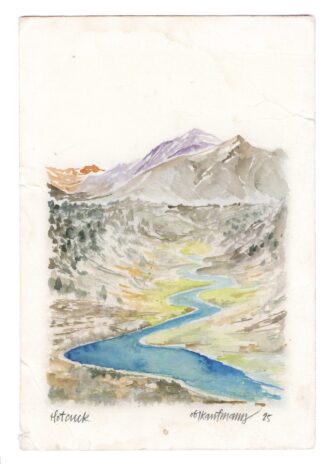

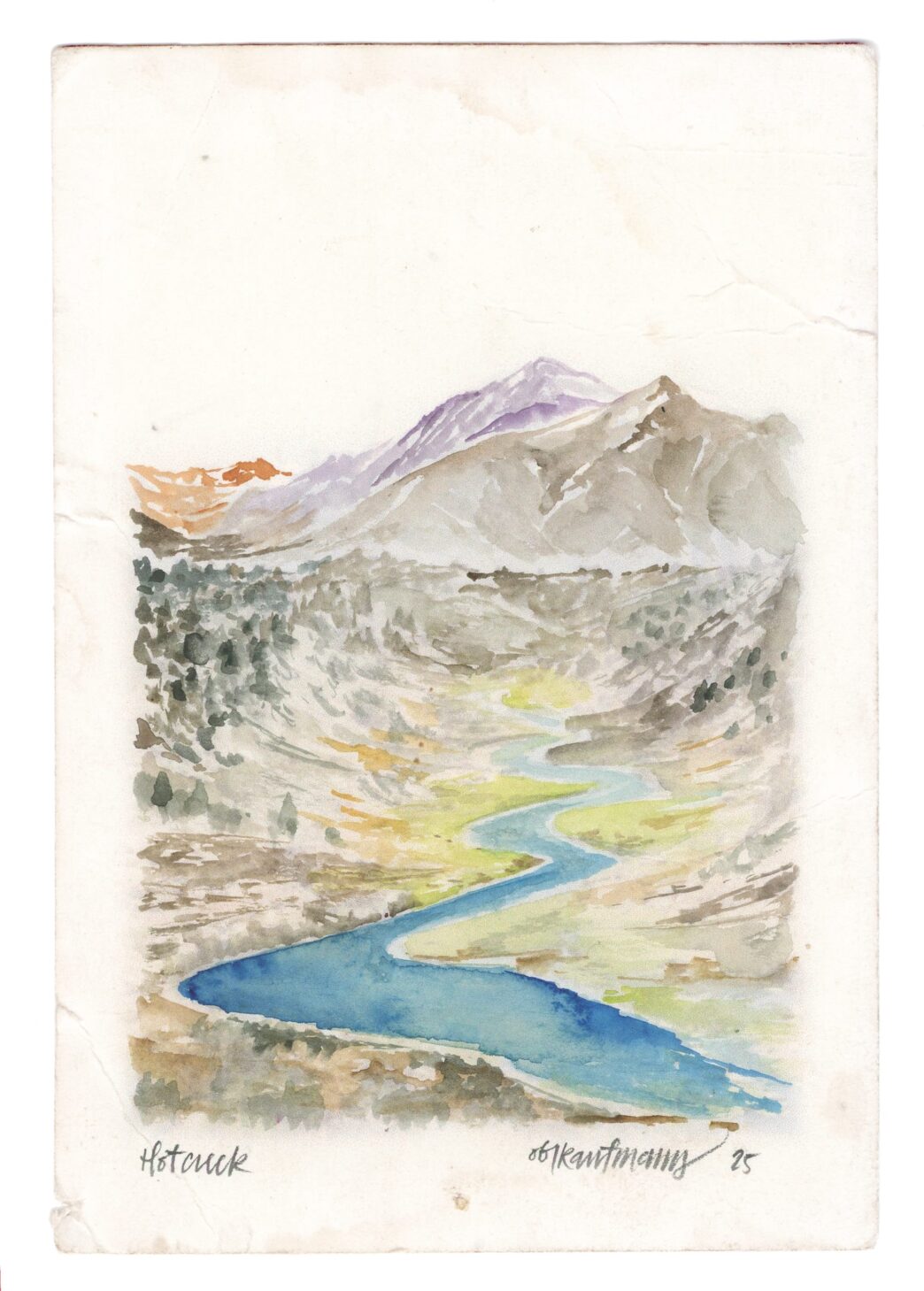

Illustrations by Obi Kaufmann

The languid meandering flow of the Upper Owens River hides the cataclysmic geologic history of Owens Valley, where one of the most violent volcanic eruptions in Earth’s recent history unfolded. This led to the formation of the Long Valley Caldera—a vast, cauldron-shaped depression that formed around 760,000 years ago, shortly after a massive volcanic eruption emptied the magma chamber and caused it to collapse. Covering roughly 200 square miles and bordered by Mammoth Mountain and the Sierra Nevada to the west and the White Mountains to the east, the Long Valley Caldera is one of the largest calderas in North America. It is notable for its remarkable hydrothermal activity beneath the surface.

The Long Valley Caldera is not the first volcanic feature in the Owens Valley area. Starting around three million years ago, the Sierra Nevada and White Mountain fault systems became active, forming the impressive relief of the Eastern Sierra Nevada and White Mountain ranges that bound the northern Owens Valley and Mono Basin region. This tectonic activity is believed to have stretched and thinned the Earth’s crust, creating a weakness where molten rock from the Earth’s mantle could rise and erupt, forming the region’s volcanic features. One of the earliest volcanoes in the area, Glass Mountain, originated about two million years ago from an evolving magma chamber within the shallow crust. From this chamber, an estimated 150 cubic miles of magma erupted catastrophically, causing the volcano to collapse. In comparison, the 1980 eruption and partial collapse of Mount St. Helens released only about 0.3 cubic miles of material, illustrating the enormous magnitude of the Long Valley eruption. The eruption of Glass Mountain was so significant that the magma chamber emptied, and the ground surface dropped as much as 1.2 miles, forming the initial caldera. Much of the erupted material fell back into the collapsed volcano, creating the Bishop Tuff, a mixture of volcanic ash and rock fragments. The extent of the Bishop Tuff is widespread, forming the well-known cliffs of the Lower Owens River Gorge, and ash fall from the eruption has been found in the geologic record as far away as Nebraska.

Volcanism in the region continued after the Long Valley Caldera eruption. Since that catastrophic event, several smaller eruptions have taken place within the caldera, forming an area of higher topographic relief between the Upper Owens River to the north and Mammoth Creek and Hot Creek to the south. This area is known as a Resurgent Dome within the larger caldera and is the source of significant hydrothermal activity. Recent geologic research suggests that a new magma chamber has formed beneath the Long Valley Caldera, as evidenced by younger volcanic eruptions as recent as 100,000 years ago. Additionally, volcanic activity outside the caldera has created the Mono-Inyo Volcanic chain, which includes Mammoth Mountain to the southwest and the Mono-Inyo Craters extending northwest to Mono Lake. This recent volcanism, along with multiple earthquakes and ground deformation over the past decades—indicating magma accumulation at depth—has led the U.S. Geological Survey to classify the Long Valley Caldera and Mammoth Mountain area as high-threat zones for volcanic eruptions.

Significant hydrothermal activity abounds in Long Valley Caldera due to its recent volcanism. In most volcanic systems, only part of the magma erupts. Magma chambers deep underground gradually solidify and lose heat to the surrounding rocks. At Long Valley Caldera, snowmelt from the Eastern Sierra Nevada infiltrates the ground and absorbs substantial heat and carbon dioxide gas from the magma. The heated water and gas rise, and when they encounter highly permeable rock like basalt, they flow eastward. As the land elevation drops east of the Sierra, the pressure on the superheated groundwater decreases, causing it to boil. This results in many hot springs and fumaroles (steam and hot volcanic gas vents) east of Mammoth Lakes.

The hydrothermal features in the Long Valley Caldera are a natural resource that offers several benefits to the public. The Casa Diablo Geothermal Plant, located near the intersection of Highways 395 and 203, harnesses this resource and produces about 30 megawatts of electricity, enough to power 22,000 homes, and has plans to expand this renewable energy facility. The Hot Creek State Fish Hatchery also utilizes this resource by mixing hot spring water with hatchery water during cold winter months to maintain an ideal temperature for fish growth. The Hot Creek Geologic Site, managed by the U.S. Forest Service, is a great place to observe the area’s unique hydrothermal features firsthand, with hiking trails along the river that allow visitors to see boiling hot springs, fumaroles, and travertine rock deposits formed from the highly mineralized waters of the springs.

HOT SPRINGS

The numerous hot springs in the Long Valley Caldera—Mammoth area offer a great chance to enjoy an immersive hydrothermal experience, getting up close and personal with the region’s unique geologic features. Most of the hot springs open to the public for bathing are located off Benton Crossing Road, northeast of Hwy 395, on the southeastern side of the Resurgent Dome. Be aware, however, that bathing in natural hot springs carries risks, as the dynamic, ever-changing conditions of these hydrothermal springs can create environments that are too hot or chemically imbalanced for safe human enjoyment. Be sure to check conditions before your visit.

- Bailey, Roy A., et al, 1976. Volcanism, Structure, and Geochronology of Long Valley Caldera, Mono County, California. Journal of Geophysical Research. February 10.

- California Curated, 2023. The Volcanic History of Owens Valley and the Long Valley Caldera. January 20.

- Evans, William C., et al, 2018. Hot Water in the Long Valley Caldera – The Benefits and Hazards of this Large Natural Resource. U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 2018-3009. March.

- Flinders, Ashton F., et al, 2018. “Seismic evidence for significant melt beneath the Long Valley Caldera, California, USA.”GeoScience World. August 2.

- U.S. Geological Survey, 2023. Long Valley Caldera Field Guide. November 20.

ARCHEOLOGY: VOLCANIC TABLELANDS PETROGLYPHS

By Sarah Rea

The petroglyphs in the Volcanic Tablelands outside Bishop are among the most awe-inspiring and intriguing sights in the Eastern Sierra. The carvings, created by the Paiute-Shoshone people who have lived in the Owens Valley for thousands of years, are believed to date back as far as 8,000 years.

The Volcanic Tablelands were created by a volcanic eruption in Long Valley over 700,000 years ago, which formed the Bishop Tuff, a red pumice. Over time, geologic faulting tilted parts of the lava flow during the formation of the tablelands, and basalt and andesite seeped through fumaroles to form darker, exposed formations. The Paiute-Shoshone peoples chipped away at the dark surfaces of the rock, exposing the lighter tuff beneath, to create petroglyphs that can still be seen today.

The art is widely varied—anthropomorphic figures can be discerned, as can clear images of bighorn sheep. At one site, there is a bas-relief carving of a miner swinging a pickaxe, the origin of which is unknown. Archaeologists classify the styles as Great Basin Curvilinear and Great Basin Rectilinear, and these styles extend east into the Great Basin as far as Arizona.

The locations of the petroglyphs are not publicized due to the unfortunate destruction of some of the ancient art. If you visit the Chidago Canyon site, you can see where chunks of the volcanic tuff have been shaved off by vandals.

When visiting the petroglyphs, bring plenty of water, watch out for rattlesnakes and cacti, and avoid touching the art, as oils from your skin can degrade the rock over time. It’s not recommended to bring dogs on this trip due to the cultural importance of the sites, as well as the dangers of steep drops and wildlife.

Be respectful of the sites—these places carry important cultural heritage for both Native Americans and visitors alike.

For more information, consider visiting the White Mountain Ranger Station (798 North Main Street, Bishop) or the Bishop Visitor’s Center (218 Main Street, Bishop). Another great option is to visit the Paiute-Shoshone Indian Cultural Center (2300 W. Line Street, Bishop), where you can view informative displays about the Owens Valley, its occupation by native peoples, and their subsequent displacement by European settlers.

About Sarah

Sarah Rea has lived in the Sierra Nevada mountains, on both the east and west sides, since high school. She spent close to a decade working in Yosemite National Park and has resided in Mammoth Lakes since 2013. She enjoys all the Sierra classics—backpacking, rock climbing, skiing, and swimming in ice-cold water. In her spare time, she chases her Brittany Spaniel and 4-year-old son all over the Eastside.

About Obi

Illustrator Obi Kaufmann is an award-winning author of many best-selling books on California’s ecology, biodiversity, and geography. His 2017 book The California Field Atlas, currently in its seventh printing, recontextualized popular ideas about California’s more-than-human world. His next books, The State of Water; Understanding California’s Most Precious Resource, and the California Lands Trilogy: The Forests of California, The Coasts of California, and The Deserts of California present a comprehensive survey of California’s physiography and its biogeography in terms of its evolutionary past and its unfolding future. The last in the series, The State of Fire; Why California Burns was released in September 2024.