If you look at a natural setting, such as a meadow or forest, your attention will naturally be drawn toward things that move, like birds, squirrels, snakes, and mountain lions.

This trait helped our ancestors find food and stay alive. The same thing happens with fish; the way your fly moves may attract them or make them bolt for safety. This is especially true on heavily pressured waters, where the fish are more wary of anglers and their flies. So, how do you make the right moves?

LIFT TWITCH AND SWING

The easiest way to add some bite-inducing movement to a fly is to modify your retrieve. For example, experienced nymphers will often incorporate a Sawyer Lift or Leisenring Lift to activate their flies and induce takes. These moves can work like magic on California spring creeks and English chalk streams, both renowned for exceptionally wary trout.

While most dry flies are fished with a dead drift, skating caddis patterns across the surface, or giving terrestrial patterns a twitch, can often get a fussy fish to take your fly. And let’s not forget the good old wet fly swing, which has been grabbing the attention of millions of fish for hundreds of years.

DANCING WITH STREAMERS

Streamer fishing is one of the most dynamic forms of fly fishing. Whether you are working the riverbank from a drift boat or covering a rip in the jostling surf, fishing streamers is a total blast. Many folks are content to use a steady retrieve, which gives the fly a consistent stop-start motion, but this is like playing one key on a piano. Learn how to work the fly using different retrieves and rod movements, and you’ll unlock a variety of grab-inducing motions. I could go into detail, but Kelly Galloup has produced excellent online videos detailing how and when to use a variety of streamer retrieves.

MAKING THE MOVE

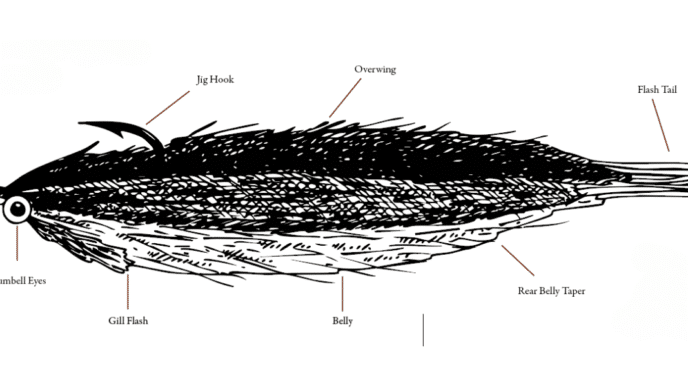

Manipulating the retrieve is the easiest way to enhance a fly’s movement repertoire, but you are limited by the fly’s physical aspects, such as materials, buoyancy, balance, and shape. For example, no matter how well it’s tied, a Bead Head Nymph will never make a good leech pattern. Designing flies so they move in specific ways takes time and effort. This is why most tyers stick with well-known patterns, where someone else has done the R&D work. However, the rewards that come from such innovative efforts cannot be overstated. A fly that does something different opens up all kinds of opportunities (and fun) for the adventurous fly fisher.

Perhaps the most obvious example of a fly designed to move in a specific way is Bob Clouser’s Deep Minnow. Bead-chain or lead eyes located at the front of the fly give it a pronounced front weight bias, producing a jig-like action when it is retrieved. This fly was originally designed for smallmouth bass but has become a fly box essential for countless freshwater and saltwater fly fishers.

Another innovative fly is Lee Haskin’s Neutralizer, a neutrally buoyant pattern initially developed for tarpon. Many years back, Lee gave me a few prototypes to take to the Everglades. I was amazed how the fly sat perfectly level and still between pulls on the line. This is how many baitfish behave when they are not feeding or fleeing. The fly was a hit with snook and redfish and has landed plenty of California surf-zone stripers, too.

The Crease Fly is a topwater baitfish pattern developed by Joe Blados that uses folded sheet foam. A lesser-known version is the Upside-Down Crease Fly, created by Phil Lee. Unlike the original pattern, the upside-down version features a downward jutting lip that makes it wobble like a Rapala lure. It’s easy to tie and, with silver or gold-coated foam, it sends out pulses of light the fish can see and a vibrato of pressure waves they can feel. Paired with an intermediate or sinking line, it gets the attention of fish from much farther away than typical baitfish patterns. When you are fishing for trout or stripers in waters measured in hundreds or thousands of acres, that extra reach can make a big difference.

TWO-STEP PROGRAM

Designing movement into your flies isn’t particularly hard, so long as you understand that lifelike movement occurs at two levels: the way water moves the materials, and the movement of the fly through the water. How you approach these two design elements determines how the fly performs.

FLOW RATES

One factor affecting fly movement is whether the water itself is moving. Materials that work well in fast rivers can be almost lifeless in stillwaters. For example, bucktail and some synthetic fibers barely move in lakes and ponds. Conversely, fast-moving water will often flatten out soft, supple materials like marabou.

Water speed also influences how the fly moves through the water. Faster water (or a faster retrieve) increases the forces acting on the fly. A relatively symmetrical fly, like a Deceiver, will generally move in a direct path, regardless of the current or retrieve speed. In contrast, an asymmetrical pattern, such as the Wobble Fly, creates turbulence that makes it wiggle. However, it is important to note that asymmetrical flies often have a performance window. An overly fast retrieve can cause the fly to spin in the water, and too much asymmetry will make them helicopter on the cast.

BALANCE

Watch underwater videos of streamers being retrieved, and you’ll notice many of them move up on the pull and down on the pause. Flies that have weighted heads or use heavy, short-shank hooks will move in this distinctly sawtooth way. This motion suggests injured prey, which can be a feeding trigger. But there are times when this does not appeal to fish, either because they have learned to avoid flies that move this way, or they are selectively feeding on prey that swims more linearly. You can reduce the sawtooth motion by moving the center of mass towards the middle of the fly. In some cases, all you need is a lighter hook. Long-shank hooks can also help.

The reverse situation applies to tube flies. A heavy hook can give the fly a “crippled seahorse” action. This could be perfect for fly fishing tropical reefs, but it doesn’t make much sense on a steelhead stream. A lighter hook will help reduce or eliminate this effect.

BUOYANCY

Sometimes, especially in stillwater and saltwater, the fish want a fly that barely floats, is neutrally buoyant, or sinks slowly. For example, trout and stripers feeding on schools of baitfish will often slash through the school. A number of baitfish end up injured or dead but not eaten. The predators will return to consume them as they slowly sink or rise through the water. Under these circumstances, a normally retrieved fly will often be ignored.

This is where the combination of an intermediate line and a neutral buoyancy fly can make for some fascinating fishing. The intermediate line will slowly pull the fly down through the water column. The fish aren’t expecting the prey to escape, so their attack is usually measured and deliberate. A slow tightening of the line may be the first indication a fish has taken your fly. Don’t let this soft touch fool you. A few years back, a friend (who we shall call David) noticed a subtle change in line tension seconds before a 24-inch rainbow hit the afterburners. It took half an hour for the poor guy to calm down.

If the fish are taking dead or dying baitfish on the surface (due to swim bladder damage), a fly that barely floats will closely match the natural. This is the streamer equivalent of fishing an emerger pattern in the surface film. Most of the time, you cast in the general direction of feeding fish, give the fly the occasional twitch, and wait for a fish to find it. However, an observant angler can often predict the path of an individual fish. You cast about six to 10 feet ahead of the fish and focus like a laser on the dimple created by the fly. As the fish nears, you wonder, “Should I twitch it one more time”? The anticipation is often so intense that you forget to breathe.

A fly that barely floats can also be useful when fishing along the bottom. The combination of a slightly buoyant fly, a short (3 feet) leader, and a fast sink line allows the fly to skim just above the bottom. Crayfish, dragonfly nymph, leech, and baitfish patterns fished just off the bottom have proven to be deadly on brown trout, largemouth bass, and halibut. One of the most brutal grabs I have ever experienced was when a largemouth took a buoyant crayfish pattern. The take was so hard, I felt it drive the soles of my feet into the boat deck.

Perhaps the simplest way to tie flies with different levels of buoyancy is to use closed-cell foam. Before you start tying, spear some foam onto the hook, and drop it into a glass of water. It’s best to add just a bit too much foam and snip off any excess once the fly is completed. Lightweight hooks can significantly reduce the amount of foam you’ll need, which helps with less bulky patterns.

SHAPE

As briefly discussed above, the shape of the fly determines how it moves through the water. This is easier to understand when we look at the lures many conventional bass anglers use. Short, flat-sided crankbaits generally produce a tight wiggle when retrieved, while longer banana-shaped lures will have a wider wiggle. Swimbaits feature a paddle or curly tail that produces a serpentine swimming motion.

By mimicking these shapes, you can produce flies with similar actions. The Upside-Down Crease Fly and the Wobble Fly are both excellent examples of flies that wiggle when retrieved. Incorporating a fly tail or paddle tail into a streamer is an easy way to get a lifelike swimming action.

PATIENCE

Perhaps the main problem with developing new flies is that you seldom get things right on the first try. The more radical the design, the more likely you are to have teething problems. Don’t be surprised if it takes an hour or two at the vise and a couple of trips to the water to iron out any bugs. That said, don’t be too quick to eliminate “failed” flies; if they do something very different, they just might be the basis for a radically new pattern.

There are very few things in fly fishing that are as cool and rewarding as developing a fly with the right moves. Do not deny yourself that pleasure.