Driving through the Salinas Valley today, you’d be forgiven if you forgot about the river winding alongside the road. Sometimes called “the upside-down river,” the Salinas is as funky a river as you will find. For most of its journey down from the hills of eastern San Luis Obispo County, it runs underground. Then, unlike most rivers in California, the Salinas runs south to north, flowing through the towns of Paso Robles, King City, and Salinas, before finally meeting the Pacific just south of Castroville. As the longest river in the Central Coast, it serves as a mirror to the Valley’s turbulent wet and dry seasons, and its history is reflected in the art and literature of the Valley, and the memories of the wild fish that used to thrash in its banks.

Even when it has water from winter storms, it’s hard to imagine that this shallow, muddy river once harbored a steelhead and Chinook salmon run. But before dams and heavy agricultural use depleted its banks, the Salinas worked as a highway for salmon and steelhead migrating to tributaries over 200 miles upstream of the ocean. However, the Valley has always teetered between long periods of drought interspersed with periods of wet years. According to early 20th-century testimonials from residents collected by schoolteacher Harold Franklin, some years the fish simply never showed up, only to turn up in good numbers the next. The fish seem to be well adjusted to this drought roulette—one of the key characteristics of the Central Coast steelhead populations has always been their ability to adapt. Years when the coastal rivers don’t breach the ocean, the fish will wait out their spawning runs until the next year, or go to the closest stream that’s open. Then, during the wet years, the rivers get a run of fish like the dry years never happened at all.

The boom and bust of the river is beautifully exhibited in the work of John Steinbeck, perhaps the most famous inhabitant and writer of the area. Books like East of Eden and Of Mice and Men take place during the depression era, and the backdrop to these stories is the polarizing nature of the Salinas Valley. As Steinbeck writes in East of Eden, “I have spoken of the rich years when the rainfall was plentiful. But there were dry years too, and they put a terror on the valley…It never failed that during the dry years the people forgot about the rich years, and during the wet years they lost all memory of the dry years. It was always that way.”

During the rich years, it was common to catch fish with spears or use barbed wire across the river to catch fish moving upstream and into the tributaries. It would take the steelhead around six to nine days to move from the mouth of the river up to the spawning creeks in the southern Salinas Valley, the area around Paso Robles. Given the wide, shallow shape of the river—even during peak flows—the fish would often throw V-shaped wakes across the surface of the water, giving away their location to locals who would spear them against the bottom. The San Antonio Mission, one of the largest missions in California, was built on the San Antonio River partly due to the abundance of salmon and steelhead that would migrate up that river. It’s clear that the run of fish was good until the dams were built on the San Antonio, Nacimiento, and Salinas Rivers—the first two being major tributaries to the Salinas.

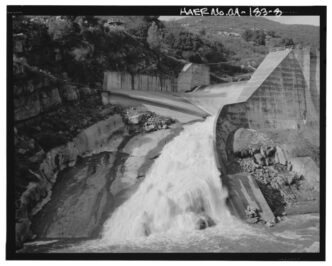

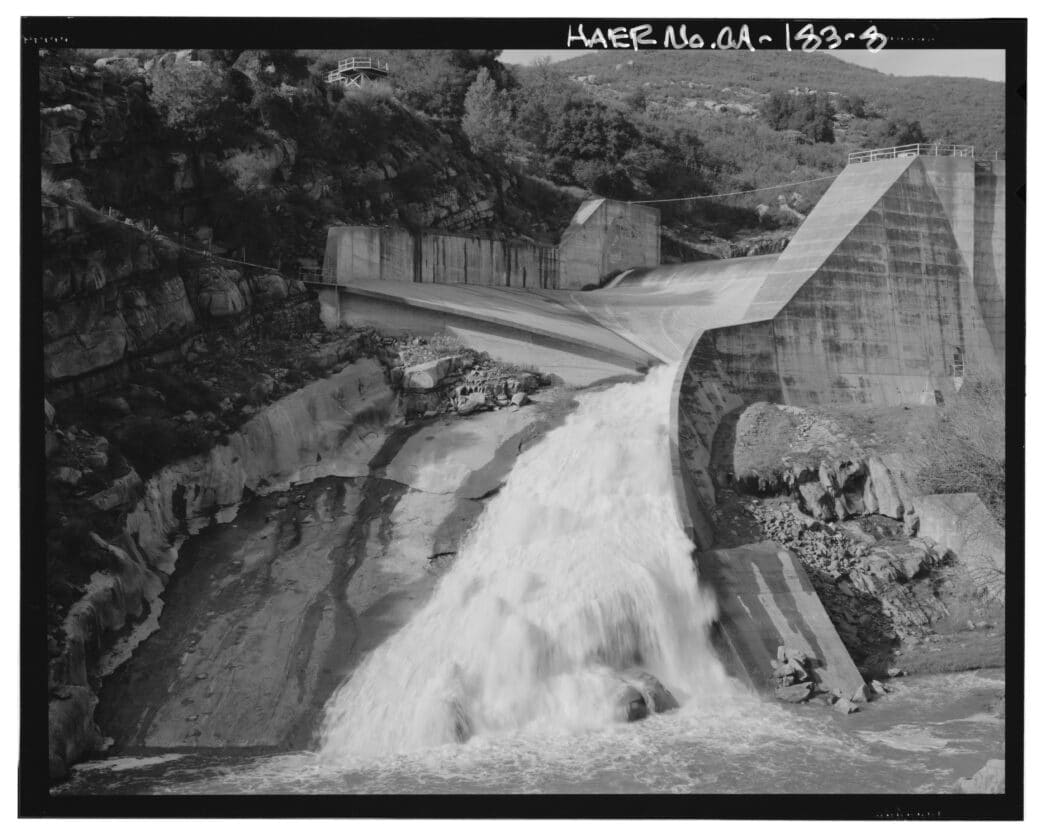

The building of the dams in the 1950s decimated the steelhead and salmon runs in the area. Built to provide a steady water supply for the agricultural use of the valley, the dams stopped any migration of fish to the spawning grounds above them. The Nacimiento Dam in particular spelled the end for any steelhead migration in the Salinas River past the Arroyo Seco, which joins the Salinas by Greenfield. As the biggest tributary to the Salinas River, the Nacimiento not only provided plentiful spawning habitat but also a significant amount of the water the steelhead needed to migrate upstream. By damming the river, the spikes in the flow of the Salinas River itself have been massively reduced in order to decrease flooding and improve the groundwater recharge. The Nacimiento Dam’s outflow is mostly a steady 60 cubic feet per second throughout the year, with a few spikes during winter to provide enough flow to the mainstem Salinas for fish to access the Arroyo Seco.

Another major impact throughout the 20th and 21st centuries has been the loss of riparian vegetation in the river channel, resulting in increased erosion and silt buildup in the river. Riparian vegetation, meaning plants that grow on the banks of the river, is not only important for reducing erosion, but also provides shade for the river, habitat for fish moving through the river channel, and acts as a filter for pollution in the water. But since 1949, around 80% of the riparian vegetation in the upper Salinas River Valley has been lost.

The impact of this loss was seen recently during the wet winter of 2022-2023, when the Salinas flooded to over 25,000 cubic feet per second during a major storm. Prior to this event, the river below the Nacimiento Dam looked like a proper river, with pools and runs. A variety of fish species benefited from the healthy habitat ranging from native suckers, pikeminnow, and the occasional rainbow trout, to invasive species such as largemouth bass, white bass, and the ultimate trophy for any fly angler in California: the carp. After the river flooded, most of the pools, deeper undercuts, and all the gravel along the bottom were filled in with massive amounts of sand and silt. Much of this came from the Estrella River, a tributary of the Salinas that also drains a vast watershed east of Paso Robles, an area primarily used for cattle farming. The loss of riparian vegetation around the tributary has significantly increased its erosion rate.

Which brings us to the last hope of the Salinas Valley steelhead population: the Arroyo Seco River. Ominously translating to “dry stream,” and the only remaining tributary of the Salinas to still have a semblance of a steelhead run, the Arroyo Seco is a stunningly beautiful river. Flowing down out of the Santa Lucia Mountains, the Arroyo Seco has carved out a steep gorge with long, deep pools. It opens up to the Salinas Valley, where for about 10 miles it has beautiful steelhead runs, and you forget you’re on the Central Coast and not the Pacific Northwest. But if you follow the flow of the river downstream during the majority of the year, it seems to disappear into the ground, with the water being pulled for agricultural use and draining the river of the lifeline the steelhead needs to get upstream. It can go five to seven years without connecting with the Salinas River, but when it does, the steelhead miraculously find their way back to it.

It’s interesting—or at least it’s interesting to me, being from Iceland and having moved to the Salinas Valley—to see the parallels between the Salinas River and the glacial rivers of my homeland. The Salinas operates on that boom and bust cycle similar to the glacier rivers that flow heavily throughout the summer when the ice melts, but drop drastically in the winter, sometimes drying up completely. The fish mainly use these rivers as a highway to get up to the spawning tributaries, going long distances just to make it to a tributary that has spawning gravel. Most glacial rivers, like the Salinas River, are too silty and sandy for fish to spawn in. It’s a testament to the resiliency of trout, especially ocean-going trout, that they adapt to these similar systems in the same manner that are halfway around the world—one in a frigid arctic climate, the other in an arid semi-desert area.

How the steelhead seem to find their way back after all that time to their native river is a feat of nature I can’t explain, but what it does provide is a bright beacon of hope in a river system that’s been dammed, diverted, polluted, and abused throughout the years. Over a hundred years ago, the Salinas River used to flow into the ecologically rich Elkhorn Slough, where it shared an estuary with the Pajaro River just to the north. The steelhead have faced plenty of obstacles. The river regularly goes years without connecting with the ocean; its major spawning tributaries have been dammed, cutting off vital habitat and the natural flow of water; invasive striped bass have infiltrated the area, feasting on steelhead smolt; the river mouth was even diverted five miles south back in 1910! But despite all of this, the steelhead have persisted.

In a time when more and more of the native steelhead waters around the west coast have been degraded, dammed, or otherwise negatively impacted by human influence, I suppose there’s a bit of comfort found in seeing the steelhead of the Salinas River system make their way up despite all the challenges thrown their way. That this river, which looks more like a desert roadway for most of the year, somehow flows enough to still work as a highway for fish making their way to the oasis of the Arroyo Seco to spawn is as remarkable a migration as any you’ll hear about.

Looking through the long history of the Salinas River and the changes the river and its fisheries have undergone can provide some comfort in knowing that steelhead do still reach some of their spawning grounds. But it also represents the warning signs of what happens when we degrade their environment in such a way that they no longer return. The upper half of the Salinas Valley has all but forgotten about the steelhead and salmon runs that used to fill every creek in the area during wet seasons. Aside from the odd “Steelhead Road” or “Trout Creek,” kids growing up in the area today have no idea what used to be. They grow up chasing bass and bluegill in the reservoirs and ponds behind the very dams that dammed the steelhead and salmon runs. They’ve never seen the native fish that supposedly made the 150-200-mile migration inland to spawn, so why would they care about restoring the fisheries?

To me, the Salinas Valley is a perfect microcosm of California steelhead issues: It is no mystery why the only remaining tributary to receive a run of steelhead is also the only undammed river in the valley. Give them a chance to reach their spawning grounds, and the fish will come even if it’s only once every few years.