I am not known for carefully watching my step, yet one occasion when I did literally watch my step taught me a lesson about ants and the fondness of trout for these tart little knobby-bodied insects. It occurred as I was walking a trail along Hat Creek in Northern California on a sunny summer afternoon. The creek was in the midday doldrums — nothing flying, nothing rising — and I was using the time to move to a favorite section that should produce a good evening hatch.

The streamside foliage crowded my path to the edge of the water, and as I stepped too near the bank, I watched as my footfall caused an eroded section of earth to collapse into the stream, exposing an in-ground ant colony. Ants were scurrying everywhere, assessing the damage to their community. Many fell into the water and floated downstream. Fascinated by the industrious carryings-on of the tiny insects, I stood watching until an almost imperceptible splurp downstream caught my attention. A trout had moved into the drift line to pluck luckless ants that fell to the stream. Stepping back, I watched as other trout began lining the bankside to suck sodden ants that continued dropping from the settlement I had disturbed. Where minutes earlier no sign of feeding fish had existed, I now witnessed a pod of trout nosed to the bank and happily lapping up the free lunch of fallen insects. The rest of that afternoon was pure heaven. My ant pattern disappeared in trout after trout.

If trout reacted that quickly to feed on stream-struck ants, I reasoned, they obviously were familiar with ants as groceries. Then why wouldn’t an imitation ant work as a midday searching pattern? Well, it does. Ant imitations make one of the most productive and consistent searching patterns that you can try. Ants always seem to be around water. Even the occasional ant that fumbles onto the water’s surface rarely goes unnoticed by the trout.

If you have had the good fortune to be on a stream or lake when a midday breeze caused a fall of winged ants, you know that trout just go crazy for them, rising like a child to ice cream or Bubba to Budweiser. They’re trout candy. However, what many Western anglers do not realize is that the lowly unwinged worker ant is a continual, if not copious reluctant commuter on the highway of the current in most streams. They fall, slip, are blown, or get washed into California’s streams on a regular basis from March through November — not in large numbers, but with a consistency that renders them recognizable to trout. Trout move to ants with a confidence born of familiarity and will rise to an ant pattern even when no ants are visible on the water.

An Affinity for Ants

Ants contain formic acid — hence the family name, Formicidae — which imparts a tart, vinegar taste. Trout must favor this taste, because they seem to prefer ants over other insects when available. Common and abundant, ants remain active and accessible all trout season and supply trout-friendly, high-value protein in convenient packages with a long shelf life. Especially on small streams or streams with a limited biomass of aquatic insects, ants and other terrestrials become the major sustenance for the trout. During the summer, the primary feeding months for trout, a number of California’s rivers provide limited insect hatches. Ants (and other terrestrials) are there to fill the fodder shortfall.

And ants are easy prey. Once waterborne, they seldom escape, making them energy-efficient offerings for foraging fish. Trout favor them as easily edible entrées, and they are a healthy meal, at that. California biologists found in tests that it might require ten midge pupae or caddis larvae to equal the calories in one fair-sized ant.

Winged Ants

Ants generally are only accidentally available to fish, and the fish do not see large numbers of ant munchies at one time. A major exception exists, however. When ant colonies expand their territories, they send out winged males and females en masse, sometimes in the thousands, to swarm and fly off with the prevailing wind. Should the wind take these flyers over a lake or river, some will fall to the water and become trapped in its surface film, providing fast-food service to delighted trout. This can be a remarkably successful time for anglers equipped with flying ant patterns to match the drowning insects. Trout go nuts for the fallen ants.

Wouldn’t it be exciting if we could accurately predict these ant falls? Unfortunately, they are influenced by the weather, inconsistent, and unpredictable, although it’s reasonable to say that the Sierra’s carpenter ants hit the air sometime in June. Swarms of flying ants can occur at arbitrary intervals throughout the season, and the angler needs to be prepared with the correct flies when a fall occurs. When you see flights of mating ants airborne, expect to see trout rising to them. When they key on winged ants, trout can be very selective. Once you witness the feeding frenzy that an ant fall can produce, you’ll vow to be prepared for the next time.

Drowned Ants

Ants are not inclined to swimming. Possessing nearly neutral buoyancy, they can float in the surface film for some time. Eventually, if not slurped by a foraging trout, they will sink and attract the wary feeders that shun the surface. Many ants, both winged and wingless, that are taken by trout are taken after they sink. Drowned ant patterns are consistent producers in any water and have performed well for me even during strong hatches of aquatic insects.

Many fly patterns have been developed to imitate drowned ants. The oldest ant patterns (before foam) floated poorly and were fished wet most of the time anyway, whether by design or not. Hard-bodied flies such as the Lacquered Thread Ant have been fished wet because they simply would not float, and they were more effective because of this flaw. Fishing a drowned ant pattern as a dropper below a floating fly is a deadly tactic on almost any water. Drowned ants deserve a place in your fly box.

Unmatch the Hatch

During the spring and early summer, when California’s aquatic hatches are at a peak, ant patterns offer a great choice for prospecting between and even during hatches. While many aquatic hatches occur within a narrow window of days or even hours, ants are always active and available. According to Mike Lawson, the fly-fishing guru of the Henrys Fork in Idaho, anglers would be well served if they learned to “unmatch the hatch.” When there are a lot of mayflies on the water and the trout become super selective, Lawson often goes to an ant pattern. He reasons that although the trout see heavy concentrations of mayflies at brief intervals during the season, they see ants awash in the current for over six months of the year. Constant exposure to the ant’s shape causes what Lawson calls a “secondary selectivity.” Trout instinctively take an ant because they are used to seeing them.

During Trico falls, when the trout seem too selective to look at your fly, try a tiny ant pattern. I can’t tell you specifically why it works, but it has saved me from many embarrassing sessions with super selective trout. It could be that the trout are in a feeding rhythm, and the ant is a recognizable commodity that they take with little trepidation. And when fish are making that splashless rise associated with the taking of midge pupa, yet your pupa fly isn’t fooling the fish, try an ant pattern. The rise forms are similar and can be easily mistaken. You’ll hardly ever see a splash, sometimes just a subtle ring or a black snout protruding above the surface.

Ant Patterns

When ants boldly establish defended perimeters around your lunch or are crawling in a long file up your pant leg, you may take this as a clue to fly selection. Tie on an ant — but not just any ant. Ant patterns — winged and wingless, fished as searchers during slow times or as “unmatchers” during a hatch — have to have certain traits if they are to be effective fish foolers. Effective ant patterns have two vital requirements, proper silhouette and visibility to the angler.

Ants possess a distinctive silhouette that trout readily recognize and to which they readily rise. Ants have six spindly legs and three body parts: abdomen (gaster), thorax, and head, with a skinny separation between the abdomen and thorax called a pedicel. Although realism would suggest tying ant patterns with a bulbous abdomen, then a skinny pedicel, followed by the smaller thorax and a head smaller yet, practicality tuned by years of testing suggests that the two-hump ant pattern is just as effective. The skinny waist, however, seems to be an identifying key for the trout and a must for inclusion on any ant imitation. For the winged variety, the wings attach at the back of the thorax and lie flared back, extending beyond the rear of the body. Wing colors range from translucent brown to clear.

Floating ants lie deep in the surface film and are difficult or impossible to follow visually. A good ant fly therefore will include some type of visual aid or “beacon” that allows the angler to locate the fly on the water. To track the fly, see how it’s behaving, watch for drag, and quickly react to a strike, I include some form of visual aid or “beacon” on all of my floating ants. It can consist of Krystal Flash or a brightly colored polypropylene yarn.

Ants are generally brown, black, cinnamon, or black and cinnamon. The black carpenter ants are the largest, suggesting hooks of size 10 or 12 for imitations. Other species require sizes down to 26. However, a size 18 wingless ant imitation is most often my go-to ant pattern, and ants in black and in cinnamon cover most of my needs. I have found occasions when a bright red or red-and-black pattern seems most effective. These bright-colored ants have saved me often, even during difficult midge hatches that have foiled my efforts. For flying ants, I find sizes 10 to 14 cover most of my needs. The successful angler needs to carry ant patterns both winged and wingless, floating and drowned.

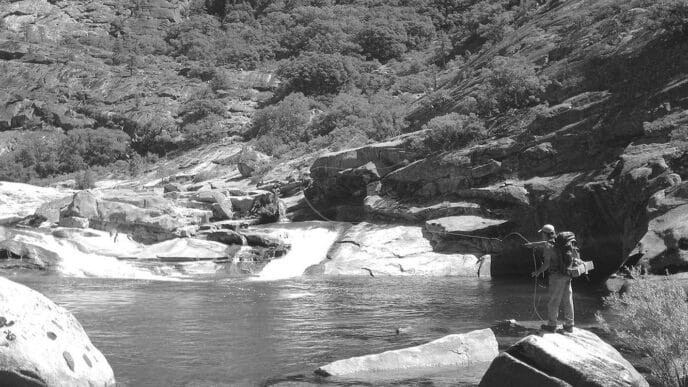

Fishing the Ant

Fishing ant patterns is as simple as it is effective. Use typical dry-fly gear and tactics for fishing floating ants: 9-foot to 12-foot leaders tapered to match the hook size and a dead-drift presentation. For drowned ant patterns, drop them a foot or two below a floating fly or fish them with a standard nymphing technique, whether under an indicator, with a tight line, or swung in the current.

Ant patterns fool fish from March through November, with May through September offering the prime time. When you witness slow, deliberate, subtle rises at times of no adult aquatic insect activity, this may indicate trout eating antipasto.

Fish your ants any time of the day, although trout are more accustomed to seeing them from midmorning on, when the ground warms and terrestrials become most active. Trout will naturally respond better to artificial ants fished where they are normally encountered. In small streams, that can be anywhere. Use smaller patterns (size 16 to 22) in slow, flat waters. In larger waters, where ants fall off streamside bushes and trees, use larger ant flies such as size 12 or 14. If trout are rising, inspecting, and refusing your fly, reduce the size by one or two hook sizes.

Ants also succumb to wind and rain. The period following a heavy rain is always prime ant time. Work the banks, eddies, and behind structure as your prime locales. Remember, however, that currents can spread terrestrials throughout the stream. The best way to fish flying ant falls is to be lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time and have the proper imitation with you. During mating flights of winged ants, the winds can deposit them anywhere, including the middle of large rivers and lakes.

Sometimes the largest flying ants you’ll encounter are not ants at all, but termites. Termites have a full waist, straight antennae, and four wings of equal length. Ants have elbowed antennae, pinched waists, and forewings longer than their hind wings. Other than these differences, termites and large flying ants are similar. Trout take the termites just as readily as they do ants.

Dig out that fly box you save for fall terrestrial fishing and restock it with ant patterns, winged and wingless, floating and drowned. Then think outside the box, Think ants throughout the season. Use them as searching patterns. Use them as unmatch-the-hatch patterns. And be sure they are available when trout key in on invasions of winged ants. Their effectiveness will impress you.

At-Em-Ants

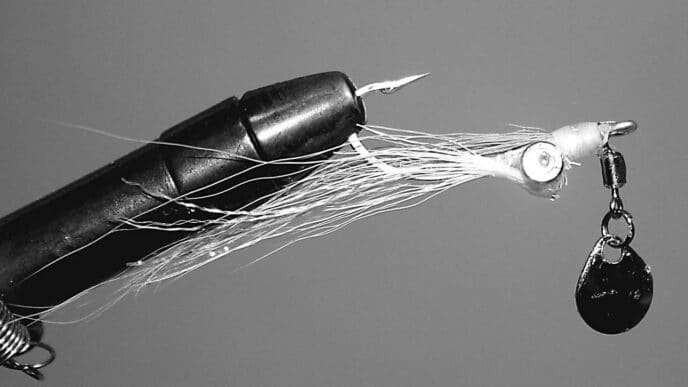

I’ve had great success with a pattern I call the At-Em-Ant, which I tie to imitate the standard ant, the flying ant, and the drowned ant. Whenever I have come upon fish feeding on ants, need to fish a searching pattern, or am frustrated by a lack of success during a strong insect hatch, I switch to my At-Em-Ants. Tied to float and tied to sink, they fool lots of fish and will fool termite eaters and ant eaters alike.

Gantner’s Standard At-Em-Ant

I tie my At-Em-Ant in all black or black and red. The foam will float the fly without the hackle, but the hackle helps to skate the fly on the surface. I use Krystal Flash to help see the fly on the water.

Hook: TMC 100 or equivalent, size 10 to 22

Thread: Black 8/0

Abdomen: 1-millimeter or 2-millimeter craft or Fly Foam, depending on hook size

Head: 1-millimeter or 2-millimeter craft or Fly Foam, depending on hook size

Beacon: Strands of clear Krystal Flash

Legs: Black dry-fly hackle tied parachute style around the beacon. Add three strands of fine rubber legs on larger sizes.

Gantner’s Drowned At-Em-Ant

For my drowned ant, I add black and clear Krystal Flash for the legs, two glass beads at the head, and black dubbing for the body. This fly is designed to sink slowly and can be used as a dropper beneath a floating ant or other dry fly patterns.

Hook: TMC 100 or equivalent, size 10 to 18

Thread: Black 8/0

Head: Two size 6 or 8 glass beads

Abdomen: Black EZ Magic Dub

Legs: Black and clear strands of Krystal Flash

Gantner’s Flying At-Em-Ant

My flying ant pattern has the addition of two-cello-wrap wings with an underwing of poly material and a sparse hackle which helps to skate the fly and provide visibility.

Hook: TMC 100 or equivalent, size 10 to 18

Thread: Black 8/0

Abdomen: 1-millimeter or 2-millimeter craft or Fly Foam, depending on hook size

Head: 1-millimeter or 2-millimeter craft or Fly Foam, depending on hook size

Underwing: Gray poly material

Wings: Clear cellophane wrap, crinkled and burned to shape

Legs: Black or grizzly dry-fly hackle wrapped around the shank. Add three strands of fine rubber legs on the larger sizes.