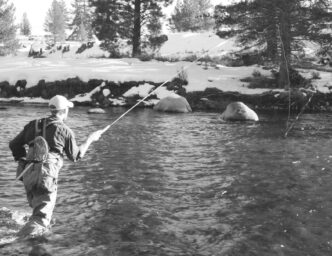

Over the years, I have watched countless people struggle with their casting. Some suffer in silence, while others feel the need to make profane comments about their rod and its parentage. I have even witnessed spectacular meltdowns in which the frustrated angler believes throwing the rod violently to the ground will “teach it a lesson” and make it cast better. These poor, tortured souls are sure they are doing everything right, and yet their fly line tells a very different story.

Many times, unbeknown to the caster, the cause of their misery manifests itself behind their heads. The problem lies with their back cast. What is often stated by casting instructors, but seldom believed by many anglers, is that every good forward cast has its beginnings in a good back cast. Simply put, a bad back cast almost guarantees a bad forward cast. Solving back cast troubles takes a bit of effort, but the casting and fishing rewards are often so profound that it is well worth it.

Looking Back

To solve most back-cast problems, you really need to be able to see the cast as it flies out behind you. Some casting instructors use video cameras to show their clients exactly what is going on. With a bright line cast against a dark, contrasting background, this technique can be most helpful. Another option is the cast analyzer developed by Bruce Richards and Noel Perkins. This device uses a tiny gyroscope, which is attached to the rod butt and wired to a small palm computer. Software loaded onto the computer displays graphs and key information on the cast. For the technically minded person, the cast analyzer is a wonderful tool.

While using the analyzer or a camcorder offers real advantages, they are often more than is needed. They also require you to stop casting to find out what is going on. As such, they are not real-time solutions to casting problems.

Thankfully, back-cast problems can be addressed by simply looking at the line as you cast. Perhaps you have tried this and found that it screws up the casting stroke. Usually, this happens because the act of turning your head during the cast causes your shoulder to move, as well. There are two solutions to the shoulder problem. One approach is to side cast, with the rod tip no more than five or six feet above the ground. In this alignment, your head has to make only small movements to see both ends of the cast. The other approach is to do your normal cast with your head facing back and simply ignore the forward cast. By keeping your head facing back, your shoulder does not tend to come out of alignment. Both approaches work well and can be used interchangeably to resolve casting problems. Let’s examine the most common casting problems that happen behind your back.

Loops

Ideally, you should begin each cast (forward or back) with the fly line forming a straight line between the rod tip and the fly. A straight line allows you to load the rod properly, which is critical for both accuracy and distance. The closer you can get to this ideal, the better your casting will be. Without a doubt, the most common backcast problem for beginners and some intermediate casters is wide loops. Most of the time, wide loops are the result of a caster simply swatting the rod backward as if they were throwing something over their shoulder. The rod tip moves in a wide arc, and the line follows suit. The subsequent forward cast has to pull the fly forward through a big semicircle, instead of along the ideal straight line.

So how narrow should your loops be? An efficient back cast will develop loops that are no more than three feet or at the most four feet across. Anything wider than this wastes cast energy.

How much is wasted? I have observed that at typical fishing distances, simply doubling the width of the back cast loop from three to six feet reduces forward-cast distance by 40 to 50 percent. Put another way, a good back cast can turn a 40-foot forward cast into a 70-foot cast with no added effort on the part of the caster.

Many anglers resort to casting harder to achieve more distance. They believe more power will gain them distance. Sadly, this is seldom the case. I have seen people cast so hard in an attempt to overcome bad loops that the rod whistles as it cuts a path through the air. Despite this display of raw power, the result is usually no better than their normal cast.

Distance isn’t the only thing that suffers from wide back cast loops. Accuracy can also be a victim. Smaller back-cast loops will help give your forward cast the precision to place your fly into tight spots. Once you master your back-cast loops, you will find yourself confidently casting to fish you could only dream about before. Big trout feeding behind sweeping willow branches, largemouth bass nestled in tangles of roots, and steelhead holding behind boulders will all become viable targets.

To address the problem of large backcast loops, you need to watch the line during the back cast and adjust your casting stroke at the same time. Perhaps the easiest way to do this is to use the side-cast technique. Grab your favorite rod and line with a simple 7-to-9-foot leader and a bit of fluff tied to the end. Find an open space such as a large backyard or playing field and begin false casting. Start off with about 20 feet of line off the tip. Don’t stop between casts, just keep false casting, and with each back cast try to make the loop a little narrower. Often, the best way to achieve tighter loops is to use the flipping paint analogy. Imagine that your rod is a paintbrush loaded with paint, and you are trying to flip paint at a specific point (where you want the line and fly to go). At first, you will probably have some difficulty trying to make this work, but you must persevere. Eventually you will find your loops getting narrower. At the same time, you will also notice that the line from your rod tip to the fly is straighter at the end of the back cast.

Once you have the loops down to three feet wide and the feel of the cast worked out, start moving from the side cast to your normal, more vertical casting style. It is best to do this while actually casting. Start with the side cast, and with each stroke, move the rod up a few degrees. I find it takes about four or five casting strokes to get back to a proper overhead casting stroke. If you lose your timing or something else goes wrong during the process, just drop back down a few degrees and get comfortable with the casting stroke again.

Don’t be afraid to spend an hour or more on this exercise. Without the ability to create reasonably small loops, your efforts on almost all other aspects of your casting will be wasted.

Tension, Slack, and Creep

No, I’m not going to talk about a law firm. Tension, slack, and creep all can have significant effects on your back cast.

You need to start each cast with the line under tension. Any cast that begins with a slack line is going to be compromised. The greater the slack, the worse the resulting cast will be.

Why is slack such a problem? Imagine a piece of rope laid out in a straight line. If you pull on one end, the other end responds immediately. Now imagine the rope has some slack in it. You have to pull the rope some distance before the other end starts moving. The same thing applies to your fly line and fly. Some of the casting arc is wasted in removing slack from the line. It is no exaggeration to say that removal of slack from your back cast will do more for your casting than the double haul, an expensive rod, or a superslick fly line.

One very common cause of slack is when the forward cast is started before the back-cast loop has completed unrolling. To go back to our rope analogy, this is demonstrated when the end of the rope is not straight, but forms a J shape. A portion of the subsequent forward cast is wasted pulling the line and fly through the loop of the J.

This particular situation is called “creep,” since the rod “creeps” forward before the line comes taut. Believe it or not, creep is often the root cause of two of casting’s most frustrating headaches — tailing loops and whip-crack casts that snap off flies.

In the case of tailing loops, the rod does not load smoothly during the cast. At the start of the forward cast, the rod tip pulls the line through the loop under very little tension. Then, when the line has completed the turn, it suddenly comes taut to the rod tip. The rod reacts to this by quickly bending downwards. Within milliseconds, the tension on the rod tip drops, the tip bounces back up, and there’s now a dip in the line. Voilà — a tailing loop is born. Whip cracks happen when the caster makes a forward cast and does not wait for the back-cast loop to unroll. The rod is moving through the casting arc at a pretty good clip just as the loop unfurls. The fly has to reverse direction so quickly that the tippet simply snaps under the strain.

So when do you start the forward cast? Some instructors suggest starting the forward cast while the back cast still has a candy-cane or J shape to it. As long as the line has only a few inches of J shape before it becomes a straight line, that approach is usually OK. But if the J shape has more than a foot or so of loop left to unroll, that will result in lost forward-cast energy.

The best way to eliminate creep is to watch your back cast and start the forward cast only when the line has fully unrolled (or perhaps more accurately, just milliseconds before it unrolls). At first, almost everyone continues to creep, even as they watch the back cast unroll. This is natural, since the casting stroke has been programmed into your brain, and it takes a while for the brain to override that memory. Recent studies have shown that the brain actually rewires itself when a task is done repetitively over a period of days or weeks. Practicing your back cast to avoid creep is the surest way to rewire your brain and deal with the problem.

Blind Casting

With enough patience and practice, you will eventually find your back cast has nice, small loops and your forward cast starts with no evidence of creep. Everything goes fine as long as you are facing to the side or backward. As soon as you face forward, though, things start to fall apart.

Relax — this happens to almost everyone. You have not yet developed the feel of a good cast. There is a neat way I have found to overcome this.

Begin with 20 or 30 feet of line off the rod tip and start casting with your head facing back or to the side. Once you have the cast going smoothly, close your eyes. Keep false casting and concentrate on the sensations in your arm, wrist, and hands. Pay particular attention to how the rod feels in your hand as you end the back cast and begin the forward cast. After a minute or so, open your eyes and continue to concentrate on the sensations in your arm wrist and hand. Once you feel comfortable with 30 feet of line off the rod tip, add an extra 2 feet and repeat the process. Keep adding line until things fall apart. As soon as the cast starts going wrong, pull in a foot of line and repeat the process.

With a standard weight-forward line, you should be able to false cast 40 feet without trouble. Knowing how a good cast feels will enable you to cast well under all kinds of conditions with everything from a 00-weight trout twig to a 12-weight tarpon stick.

Practice, Don’t Procrastinate

I know it’s not as much fun as actually fishing, but a few hours diligently working on your back cast will improve your fishing immeasurably. Don’t fool yourself into thinking that you will solve your back-cast problems on your next fishing trip. You know as well as I do that that is a politician’s promise. As soon as you get on the water, you will be fishing. Besides, time on the water is simply too valuable. Set aside an evening or weekend and clean up your back cast. Once you have done so, fish that used to be too far away or too difficult to cast to will become viable targets. You really will catch more and bigger fish. If that isn’t reason enough to work on your back cast, I don’t know what is.