By their very nature, rivers and streams are special places. The sound and movement of water is at once exciting and soothing. Healthy watercourses sustain vegetation, bird and animal populations, aquatic invertebrates, and, of course, fish. They also nourish people, not simply as water sources, but also as connections with a world beyond ourselves. As anglers, we seek the secrets of streams and look for their hidden stories.

At the same time, there is a sense in which we take them for granted. I mean, once a stream is established as a part of the landscape, we just assume it is always going to be there. Rush Creek, which flows into Mono Lake in the eastern Sierra, tells a different tale. It has disappeared, the victim of water diversions in the dry eastern Sierra climate, and then it has reappeared, thanks to efforts to bring it back.

There and Gone

A vintage photograph from the 1920s shows several men holding impressive stringers of trout. All of the fish look to be more than a foot in length, with several half again as large. The men are standing next to Rush Creek in an area known as “the bottomlands.” In the background is a landscape lush with trees, and a large pool is visible. The bottomlands contained a wide riparian forest composed of cottonwoods, willows, and pines. The stream flowed in a sinuous main channel with numerous side channels. There were productive spawning gravels, exposed willow roots and fallen trees, and this structure provided excellent fish habitat.

The brown trout population of the stream was so impressive that Rush Creek served as a destination for fly fishers from as far away as Europe. Sporting journals in New York ran articles extolling the creek. John Dondero, who was raised in the Mono Basin in those days, told an interviewer: “We caught the 25-fish limit most of the time, and they were all wild browns, 12, 15, and 16 inches. One time a guy pulled an eight-pounder out of Rush Creek above the lower bridge in the meadows.”

That bridge is no longer there. Neither are the pools, the riparian trees, and the meadows themselves. They went away with the water. This wonderful stream was gone by the early 1980s. A woman with whom I often fish tells me that when she and her family would drive up Highway 395 on vacations, she would cross over Rush Creek and wonder if there would be any water there.

My first view of the stream, in the early 1980s, was of a dry bed of cobbles and dead and dying trees and shrubs. Little did I know that this desiccated husk of a waterway was about to be reborn and begin to regain some of its historic glories as a sport fishery.

Gone and Brought Back

Rush Creek has long attracted the attention of those who believe they have a better use for water than leaving it in the form of a free-flowing stream. In the early twentieth century, the Rush Creek Mutual Ditch Company concocted a plan to divert the creek around the south end of Mono Lake to irrigate potential farms on the north, east, and south side of the lake. The plan failed when porous soils absorbed all of the water. More successful was the construction at the present location of Grant Lake Reservoir of an earthen dam built for the purpose of irrigating surrounding acreage.

In 1941, the City of Los Angeles completed construction of the existing impoundment at Grant Lake, creating a 47,171-acre-foot storage capacity. As part of the second phase of the Los Angeles Aqueduct Project, water from four of Mono Lake’s tributary streams was then diverted through a tunnel beneath the Aeolian Buttes to the upper Owens River, transforming the Rush Creek watershed into a part of the Owens River drainage. The 8.7-mile stretch of creek between Grant Lake dam and Mono Lake was severed from natural flows. The stream, of course, suffered: channels dried up and riparian vegetation vanished as mature stands of willows and cottonwoods became diseased and died. In wet years, runoff exceeded the capacity of Grant Lake Reservoir, and spring floods would flow over the dam’s face, causing further degradation of the streambed. These high-water events straightened the stream course and scoured the bottom, leaving a rubble of bare cobbles, collapsed unprotected banks, and side channels plugged with debris.

Then a series of wet snow years in the early 1980s brought small flows to dried-up Rush Creek. Overflows from Grant Lake not only brought water, they also carried trout. In October 1984, Mammoth Lakes resident Dick Dahlgren visited Rush Creek below the dam and saw fish in the water. Being an accomplished fly fisher, he caught some of these fish and began to report their presence to anyone he could. The presence of the fish led to various legal proceedings and negotiations that wove their way through the California courts and ultimately to the State Water Board. In 1994, the California State Water Resources Control Board issued Decision 1631, which established streamflow mandates for Rush Creek and required the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power to prepare and execute a plan for Rush Creek’s restoration. This was followed in 1998 by Orders 98-05 and 98-07, which further refined the restoration requirements.

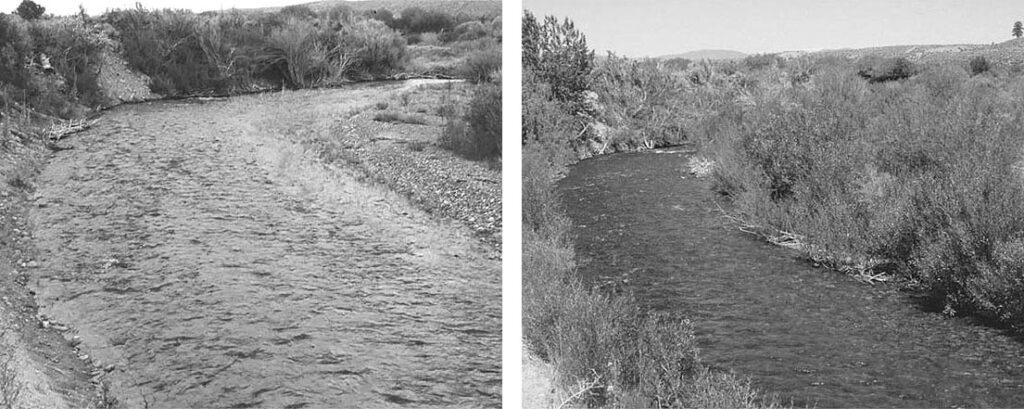

The consequences of these orders can be seen in many ways. A pair of photos shows a stretch of the stream in 1987 and 1994. The “Before” shows a naked stretch of water devoid of vegetation, with a wide, shallow, featureless channel without defined banks. The “After” photo shows a much more inviting creek, lined with willows that anchor the stream banks. The creek has become more defined and begins to show signs of ecological health.

Rush Creek is now the subject of intense monitoring as various restoration methods have been put into place. Among the factors that have been tracked for more than 10 years are daily stream flows, water temperatures and other measures of water quality, stream morphology, vegetation types and acreages, and trout populations. The monitoring and restoration process is known as “adaptive management,” described by Lisa Cutting, policy director for the Mono Lake Committee, as “an approach used to address uncertainty by viewing actions as experiments derived from hypotheses — conducting extensive monitoring, evaluating the results, and then determining if the assumptions and current management need to be changed.”

Water flows are now strictly managed, except in heavy snow years, which can still result in dam overflows that can swell the creek. However, the overall objective of the process is to reinstate natural processes to the greatest extent possible. The State Water Board’s direction at the time of Order 98-07 was that Rush Creek be restored to a condition approximating that before the diversions began. “Termination criteria” have been established that, when reached, will allow for the scaling back of monitoring activities on the assumption that the system has been brought into a stable state of functioning. These criteria include both trout size and population numbers and the physical characteristics of the stream, such as channel lengths, sinuosity, and the total acreage of woody riparian vegetation.

Fishing Rush Creek

As the restoration continues, Rush Creek has begun to reemerge as a viable trout fishery. Although it can be considered a relatively small stream, it deserves attention from fly fishers because of the lessons it provides in water law and fishery restoration, and because one reason Rush Creek was brought back to life was that the stream had been an important recreational fishery prior to its diversion to the Owens. Besides, fishing the creek now requires considerable bushwhacking, and there’s nearly 9 miles of trout water to explore downstream of Grant Lake. The restoration process is by no means complete, but the overall trend is positive. The creek is surrounded by an expanding zone of willows, wild rose, and other vegetation. Structure is emerging, insect populations have come into being, and the formerly dry areas are now home to trout. Although side channels are beginning to reappear, the blow-out events severely straightened the streambed, and water still flows quickly through Rush Creek. As trees and woody debris fall into the channel, though, pockets and small pools are beginning to emerge. The banks have begun to be anchored and defined by the willow stands, and undercut banks are beginning to evolve. The willows and other vegetation create shadows and overhanging vegetation that function to keep the stream cooler. That, in turn, attracts trout. I fished Rush Creek on the kind of August day that brings people back again and again to the Mono Basin. Deep-blue sky framed the peaks of the Sierra Crest, and heat waves shimmered above the expanse of Mono Lake. From where we parked, we dropped down toward the stream, slogging our way through tangles of sage, rabbit bush, and bitterbrush. I could hear the creek, though I couldn’t see it — it was hidden behind mounds of wild rose and a curtain of heavy willow growth all along its banks. Some of the willow copses were 20 feet tall and quite dense. There is no trail — you just force your way through until, suddenly, the creek is at your feet. Its water looks inviting, but if, like me, you wade wet in shorts, expect to wind up with plenty of scratches on your legs getting to and from the stream. There is no tree canopy, and the sun can be intense, even at 10 o’clock in the morning.

A typical pattern on Rush Creek is for the stream to flow quickly in a fairly straight path for about 35 yards or so, then take a slight jog where a large root ball or other structure breaks up the current and calmer water forms behind the obstruction. Cobbles and gravels line the bottom, riffling the surface. It is important to stop and look around, because at first glance, the stream appears the same from bank to bank, but a closer examination reveals deeper slots, both in the center of the stream and at the edges.

The water is refreshingly cold, but clear, so it is easy to put fish down. Approach slowly and quietly, and, as is the case with almost every stream, it’s best to avoid the hours of midday, when the sun is overhead and the trout are shy.

When I was there, mayflies danced above the willows and slight bulges appeared in the surface at the far bank. One of us tied on a Blue-Winged Olive emerger and the other a Blue-Winged Olive parachute, both size 18. The creek is a tight fit, with willows crowding behind and branches hanging right over the water, and we spent a lot of time retrieving errant flies. Rush Creek calls for short casts, which often require imaginative techniques. You can achieve only short drifts, so accuracy is at a premium. After a few preliminary efforts, we were rewarded with brown trout of about 10 inches, vibrantly colored a brilliant gold. The trout range up to 14 inches, with rumors of larger fish. The majority are like those that we caught — in the 8-to-10-inch range. They are strong fighters, especially in the fast current.

Rush Creek’s fish are browns and rainbows. The creek here is not stocked and will not be stocked. The fish are now able to spawn in the creek, and the population is moving toward being self-sustaining.

The creek supports populations of mayflies, caddisflies, a species of large stonefly, and midges. Hatch timing is roughly similar to that on Hot Creek, although the insect populations are much, much smaller. The fish are often finicky and selective. Productive dry-fly patterns include Blue-Winged Olive and Adams parachutes, Paracaddis emergers, Headlight, E/C, and Elk Hair Caddis patterns, and midge emergers. Grasshopper imitations are a good bet beginning in mid-July, as are Stimulators. Generally, I lean toward size 18s or even smaller sizes. I most recently fished with a 9-foot 6X leader extended with another 2 feet or so of tippet. Nymphs are also productive. Try short drifts through the deeper slots and occasional pool using size 16 or smaller Hare’s Ear or Pheasant Tail Nymphs, Zebra Midges, or WD-40s.

Because the recovering trout population must be monitored and measured, the stream is subject to special fishing restrictions from Grant Lake downstream to its confluence with Mono Lake. Anglers are limited to artificial lures and/or flies with barbless hooks and must release all fish that are caught. These regulations facilitate the monitoring of the trout population and continued progress in the creek’s recovery. The removal of fish would impede the determination of the progress being made toward the court’s definition of adequate restoration. A proposal has been advanced to remove the artificial-lure restriction and open the entire creek to the use of bait. (Fishing Rush Creek from the Silver Lake outlet to Grant Lake is unrestricted, and the stream there is heavily stocked.) A two-fish bag limit is also being proposed. The theory behind this idea is that the resource (that is, the fish population) is underutilized and thus being “wasted.” This proposal raises concerns that the restoration efforts may be compromised and that the return of the creek to its historical conditions could be delayed or prevented. The discussion is in its very early stages, but it bears watching.

Many factors influence our angling choices: the presence of trout, the likelihood of hooking up with large fish, the challenge posed by difficult fish and conditions, or the pleasure of a less sophisticated quarry and open, easy fishing. Sometimes it is the significance of place. For me, to fish is to become involved in something greater than oneself — in the landscape, the solitude of wilderness, a connection to natural processes. I want to fish the waters that are home to what may be descendants of the original populations of California’s native trout or to follow trails described in early journals of Sierra exploration, before we intervened so massively and transformed the natural environment. That isn’t always possible — just because a stream once flowed, we can’t assume it is always going to be there. The fact that there even is a lower Rush Creek in which to fish is, to me, something of a miracle. It is a demonstration of treasures lost, of vision and perseverance in their recovery, and of the possibilities of human cooperation. It is also an example of the potentials and limitations of the natural world to heal itself and of the kinds of lessons people can learn about resource restoration and management. If you visit this place, tread gently and treat it with care and respect. It was nearly lost to us.

If You Go…

The restored section of Rush Creek is situated 5 miles south of the community of Lee Vining in the eastern Sierra. It flows approximately 8.7 miles from Grant Lake Reservoir to where it enters Mono Lake. The North June Lake Loop Road runs from Highway 395 to Grant Lake. The nearest road to the section of the creek below Highway 395 is Oil Plant Road, which runs east of Highway 395 north of the intersection of Highways 395 and 120 East.

Food, supplies and lodging are available in Lee Vining, including the justifiably famous Whoa Nellie Deli at the Mobil Station near the junction of Tioga Pass Road and Highway 395. Food, lodging, and provisions can also be found along the June Lake Loop Road, and there is a fly shop in the community of June Lake. Campgrounds can be found along the lower stretch of Tioga Pass Road and the June Lake Loop. Contact the Inyo National Forest at (760) 873-2408 or (760) 647-3044 for more information about camping. The area is depicted on the Inyo National Forest map available at the Mono Basin Scenic Area Visitor Center located north of the town of Lee Vining.

Take plenty of water and sunscreen. The sun in the Mono Basin can be very hot, the air is dry, and there is not a lot of shade. Biting insects, not just mosquitoes, can be a problem, so bring and use an effective repellant.

In wet years, when water spills over the dam at Grant Lake, flows in Rush Creek can rise to more than 350 cubic feet per second, making it quite difficult to fish. Real-time flow data can be accessed from the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power website at time.htm.

To learn more about the Mono Basin and its history and restoration, visit the Mono Basin Scenic Area Visitor Center and the Mono Lake Committee Information Center and Bookstore (the former is on the east side of Highway 395, while the latter is on the west side in the middle of town). Both locations feature displays and many books on the subject. Information about the history of Rush Creek, the process that resulted in the restoration orders, and the present status of the project can be found at the Mono Lake Committee website, http://monolake.org.

Peter Pumphrey