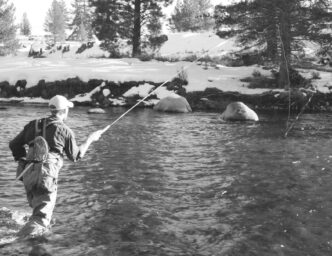

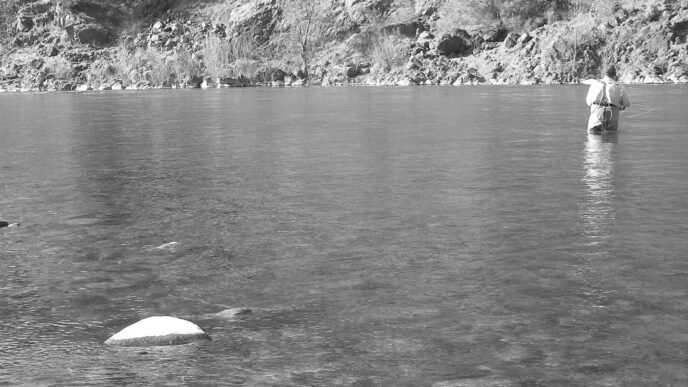

Shooting heads are the machine guns of the fly-line world. In the right hands, they cover more water, more efficiently, than any other fly line. You can cast a shooting head a long way, and one reason why is design of the shooting line that backs it up. What kind of shooting line you choose matters, because you’ll spend most of your fishing time actually handling the shooting line, not the head. A shooting head is a length of specially constructed fly line — floating, intermediate, or sinking, depending on the application, and usually around 30 feet long, although sometimes less (or even more), depending on the weight in grains of the material used. It’s attached to a thin running line that shoots through the guides like a tracer behind the bullet of the head. Watch a skilled shooting-head caster, and you will immediately notice how quickly and effortlessly he or she slings the head and running line across the water. Using a simple water haul to load the rod, the angler makes just one back cast and one forward cast to deliver the fly 80, 90, or even 100 feet away. In as little as three seconds, the angler’s fly is back in the water and earning its keep. Even a skilled caster would need almost twice as long to cast a weight-forward line that far.

Over the course of a full day of fishing, this translates into more actual fishing time, which as we know usually means more fish. If you think about it, it’s really not surprising that steelheaders developed the shooting head. Do the math. If the steelhead is the fish of ten thousand casts, a shooting head cuts the time between fish by eight hours!

Not just shooting heads, but shooting-head casts are different. With weightforward lines, a 100-foot cast (assuming you have the necessary skill) typically requires false casting about 60 feet and then shooting the remaining 40 feet of line. Shooting heads are pretty much the reverse. You usually make one false cast with about 40 feet of line out of the rod and then shoot the remaining 60 feet. This is why most shooting lines are thinner than the running line on a weight-forward line. Less line mass means more distance.

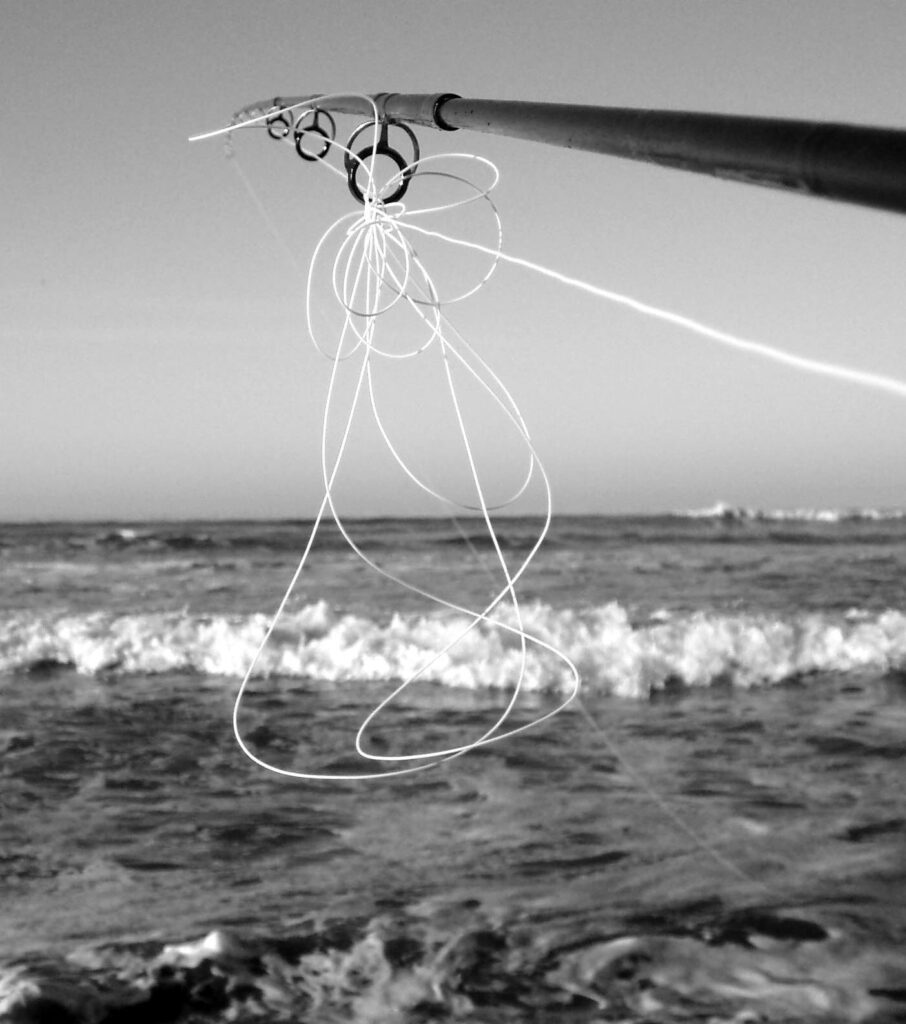

However, this diameter/distance compromise can come at a cost. Shooting lines can be prone to tangling. Unless you know how to select and manage your shooting lines, repeated tangles will often lead to frustration and colorful language. With the right shooting line, you can fish a head in some pretty gnarly conditions and experience only the occasional tangle.

Shooting lines come in three basic flavors: monofilament, plastic-coated lines, and lines made with braided mono or braided gel-spun polyethylene. Each has its place in a fly fisher’s arsenal.

Monofilament Lines

Monofilament was the original shooting line. Just after World War II, Jim Green introduced the world to the combination of shooting head and mono shooting line. He stunned the fly-casting world by breaking several world distance-casting records. Ever since then, mono shooting lines have dominated the ultimate distance records in fly casting.

Mono is still a very popular shooting line. It has three distinct advantages over other shooting lines. It is light, thin, and has a very slick surface. These three factors make it “the” shooting line when distance is the primary criterion. Its thin diameter and density, slightly higher than that of water, also make this a good choice for

when you need to fish deep. Because it’s thin, mono offers less water resistance, and it sinks fairly well, allowing a sinking shooting head to plumb the depths more quickly and to stay down longer. For example, when I am fishing the reefs in Monterey Bay, I often use tungsten-impregnated heads and mono shooting lines. With this gear, I can drop the fly down 60 feet to where prehistoric-looking lingcod and stop-sign-red vermillion rockfish hang out. You just can’t do that with a con-

ventional fly line. Also worthy of note is the fact that most brands of mono shooting line are quite inexpensive. A spool of regular mono shooting line will leave you with plenty of change from a ten-dollar bill. Given all of the positive aspects of mono, why would anyone fish anything else? In one of those too-good-to-be-true facts of life, the very traits that make mono a good shooting line can also make it a bad shooting line. Being thin and slick, it can be difficult to grasp with cold, wet hands. Anglers with limited finger dexterity will quickly learn to dislike mono. Also, under windy conditions, mono can get blown around, making retrieved line a management headache.

There are a number of mono shooting lines on the market. Basic mono shooting lines are very much like the stuff that conventional-tackle anglers spool onto their spinning and baitcasting reels. Aside from the fact that mono shooting lines tend to be in the 25-pound-test range and hence heavier than what’s found on most conventional reels, the only real difference is that the shooting line has a slightly different chemistry, which reduces its memory. “Memory” is a term used to describe the way in which a material will assume the shape of any object on which it is stored. In the case of shooting lines, memory manifests itself as coils of line that are the same diameter as the fly reel.

You need to try casting a coiled line only a couple of times to realize this is not a desirable trait given the tangles that result. To erase this memory, most anglers simply stretch the line between their hands prior to casting it. A few good tugs and the line becomes straight. Another option I’ve used is to soak the shooting line in water for several hours.

Recently, the folks who brought you better living through chemistry have developed mono shooting lines that float. They achieve this by producing monofilament with air channels inside. These lines are a bit thicker than solid mono lines of similar breaking strength, but still thinner than other types of shooting line. The downside is that they are not cheap. A floating mono shooting line will cost you about as much as a good plastic-coated line.

Plastic-Coated Lines

Thanks to advances in chemistry and engineering, coated shooting lines have undergone significant advances over the past decade. Back in the early 1970s, when I started using shooting heads, coated shooting lines were a mixed blessing. They were easier to handle than mono, but they were not very durable, and their coatings quickly became marred and cracked. You were lucky if you could get a season of use out of them. These days, you can buy lines for use in cold or warm water that have superslick coatings and the durability to last three or four seasons of very hard use. You can select floating or intermediate shooting lines to fit whatever fishing needs you may have. Two companies have even come out with shooting lines that feature a textured surface, which is claimed to reduce friction in the guides and thus add distance.

Quite frankly, with the exception of using mono to fish deep water, I see little point in using anything other than coated shooting lines these days. They are easy to handle, have little memory, and don’t tend to get blown around like both mono and braided mono can. The only downside is that at between $25 and $70, they are not particularly a bargain. But when you consider their utility and durability, the extra cost is not that hard to swallow.

Like monofilament lines, coated shooting lines usually need to be stretched to remove memory. I often do this by attaching my fly to something like a tree branch or post and then walking off as much line as I expect to cast. I pull steadily on the line for a few seconds and then gently reel it back or put the line in my stripping basket.

When selecting coated shooting lines, you need to consider water temperatures. With running lines, as with full lines, line manufacturers offer lines that are designed to work best in cold or warm waters. Believe me, it is no fun trying to cast to winter steelhead with a shooting line designed for warm water. It’s always a good idea to check the manufacturer’s website before making your final selection.

Coated shooting lines benefit from regular cleaning. There are a number of products on the market specifically designed for fly lines. Most of these products do a good job of cleaning and temporarily lubricating shooting lines. I spoke to Bruce Richards about these products, back when he was the line guru at Scientific Anglers. He told me that most line cleaners are based on silicone, and as long as they are designed specifically for fly lines, they should be fine. He warned me against using other plastic-polishing products. While many will create a slick surface, they may also contain compounds that can leach out the plasticizers that keep the line from cracking. Use of these products could shorten the life of your line. He said that best way to clean a line is to soak it in soapy water (regular hand soap), run it through a clean rag, then rinse off any residual soap with fresh water. I typically do this after each fishing session (especially important when plying the line in salt water environs), and the results are as good as, if not better than, those obtained by using the commercial cleaners.

Braided Monofilament

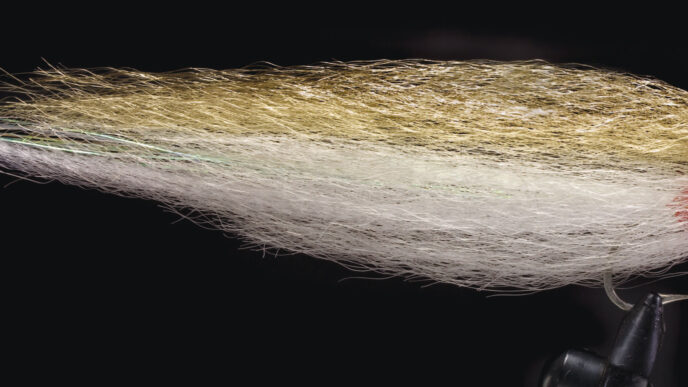

Braided monofilament is basically 16 strands of light monofilament that are woven together by a special machine to create a hollow braid. This type of shooting line has been around for quite some time and is still used by many fly fishers. Unlike monofilament, braided mono does not exhibit any significant memory, so it can be fished without any stretching or soaking. It is also light, which helps with distance. The most commonly used braid has a breaking strength of 35 pounds and a diameter of about 0.045 inches. The braiding also provides a slightly textured surface. Consequently, braided mono is easier to hold onto than regular mono during casting and fishing. The texture is also the downside of braid, because it can abrade and even cut into wet flesh. Gloves or a stripping guard are a good choice when using braided mono. Braid can also be a problem for people fishing in waters with a lot of suspended sediments. The weave can capture fine sand particles, in effect creating a long, thin abrasive. This can create grooves in the rod guides, with the tip top usually being the first to show damage. I don’t use braid too often when fly fishing the surf for this reason. While not as cheap as monofilament, 50 yards of 35-pound braid usually costs less than $15.

Superbraid (GSP) Lines

With virtually no stretch and exceptionally thin diameter, gel-spun polyethylene (GSP) provides many conventional-tackle anglers with superior fishing performance. Theoretically, it should make a superb shooting line for distance casting. Unfortunately, no one I know has figured out how to overcome the tendency of GSP to tangle and knot when used for that purpose. In addition, GSP can act like a guillotine on wet fingers. In an effort to address these problems, several line companies have combined GSP with other line types. One approach has been to thread GSP inside braided mono. The resulting line has almost zero stretch and pretty good tangle control. Another approach is to coat the GSP with a plastic (polyurethane) coating, like other coated lines. These lines have very little stretch and surprisingly little memory. While a bit pricey, the polyurethane-coated GSP lines have become my preferred shooting line for many fishing situations.

What About Distance?

For tournament distance casting, mono is still the king. This is based on the simple fact that mono is much lighter than other shooting lines, and its smooth surface produces less resistance when running through the guides. However, tournament fly casting is somewhat removed from actual fly fishing, where tackle has to be usable on the water and most casts are not exhibitions of extreme precision and speed. Over the years, I have heard a number of fly fishers say that mono shooting lines enable them to cast much farther. This has become a sort of truism that everyone accepts. Surprisingly, no one that I have talked to has actually tested this theory. I did.

One cold November day last year, I decided to compare the real-world distance performance of the most popular shooting lines on the market. For this test, I used a popular $210 7-weight rod, a 270grain 30-foot high-density head, and a 9-foot leader. This is the sort of gear many of us use when fishing large lakes, big rivers, and the surf. I removed the hook point from a 2-inch size 4 streamer and knotted it to the leader. I tested five shooting lines: 25-pound Amnesia mono, 30-pound braided monofilament, braided mono with a nonstretch GSP core, a standard plastic-coated shooting line, and a plastic-coated shooting line with an embossed surface texture. I took this lot to a local school playing field and found a quiet corner. I cast each line 10 times and measured every cast against a tape.

The results were quite interesting. Monofilament did indeed provide the longest average casts at 110 feet. However, the other lines were not that far behind. Braided mono and the plastic surface-textured lines both averaged a very respectable 106 feet. Just behind them was the standard plastic-coated line at 104 feet. The nonstretch GSP-cored braid had the lowest average distance, but at 101 feet was only 9 feet less than the distance leading mono. Based on this testing, I have come to the conclusion that when it comes to actual fishing distances, pretty much any shooting line on the market will get the job done.

Managing Twist

The most common problem with all types of shooting lines is tangling. You start casting, and everything is fine. Then, after 20 or 30 minutes, you start to notice that your line has begun to tangle more and more frequently. Eventually, you find almost every cast results in a goober of shooting line wedged in the stripping guides. The problem is not the line; it’s the cast. Believe it or not, your casts are forcing twists into the line, and these are causing the profanity-inducing tangles. There are two ways this happens. The first occurs when making roll casts and is particularly evident when using intermediate or sinking heads. When using these heads, you often have to make one or two roll casts to bring the line up to the surface so it can be cast normally. As the line is drawn back to form the typical roll cast D loop, it passes below the rod tip. Then, as you execute the forward roll, the loop goes over the rod tip. This motion has rotated the line relative to the rod tip and forced a single twist into the line. Repeated roll casts drive more and more twists into the line.

In addition to roll casts, an oval casting stroke when making a standard overhead cast can also result in twists. This is particularly common with dense shooting heads, because the line often flies below the rod tip on the back cast. Then, on the subsequent forward cast, the line goes over the rod tip. Just as with the roll cast, you have added a twist to the line.

At first, the natural elasticity of the line enables it to absorb the twists. Eventually, the number of twists exceeds the line’s elasticity, and the section between the reel and the first guide starts to develop a telltale spiral shape. This is when the tangles start. If you don’t pay attention and keep casting away, the tangle-inducing coils become tighter and tighter. This inevitably leads to more tangles. Eventually, you reach a point where almost every cast comes to a premature halt.

Fortunately, there are simple solutions to these problems. In the case of coils induced by roll casts, the answer is to alternate casting on your left and right sides. By doing this, each roll cast undoes the twist from the prior cast. For overhead casts, you have two choices. The obvious solution is to make your back cast go over the rod tip. If this is not practical, and with very dense heads it can be tough, another approach is to cast out far enough to have a tight line from reel to fly. You then point the rod directly in line with the fly line and hold it loosely in both hands like a ladder rung. By rotating the rod along its long axis, you unwind the twist. Right-handed casters should rotate the rod clockwise. Southpaws should go counterclockwise.

After fishing, I usually remove any residual twist when I clean the line. The twist is removed when you pull the soaped line firmly though a piece of cloth and drop it into a bucket of clean water. An alternative I sometimes use is to stretch the line between my two garden fences (it helps to have a big lot). The reel is secured with a large cup hook on a fence post. Under a moderate drag setting, I’ll pull the line out and hook the leader loop onto a ball-bearing swivel, which is attached to a post on the far. I then set the drag to full on and pull the cleaning cloth firmly along the line towards the leader end. The twist gets spun out by the swivel.

Careful selection of your shooting line and careful management can make shooting heads an incredible fishing tool. With the exception of trolling, no other fly-fishing technique can cover as much water as a shooting head.