In California, we are blessed with many winter angling options for trout and steelhead. During the winter months, avid fly fishers can be found on east-slope and west-slope Sierra streams, valley and coastal steelhead rivers, and many of our still waters. Winter anglers frequently worry about contending with high and off-color water, but the opposite circumstance causes almost as much consternation.

Low, clear, and cold water provides a unique set of challenges to the winter fly fisher. Fish are spooky and lethargic. Hatches are sparse, and the bugs are very small. Ice builds up in the line guides. Trout and steelhead hunker down and hold in places that are hard to fish. Fortunately, there are strategies that can help anglers persevere in these uninviting conditions.

When One Size Does Not Fit All

Most anglers who have been at it for a while settle on a go-to rigging for certain types of trout fishing. For example, you might like a one-inch Thingamabobber on a 9-foot 3X leader for nymph fishing. Add a couple feet of tippet, some split shot, and a couple of nymphs. Sometimes it’s a little on the heavy side for certain holes, and sometimes it’s not going to get deep enough, but it’s a good compromise, and it works for most spots you fish.

Adopting a one-size-fits-all approach is convenient because it allows you to spend more time fishing and less time rigging. However, this particular rig may work well in high or fast-moving water, but may be less effective when rivers are low and clear. Low and clear conditions usually result in spooky fish. The fish can see you from far away and will easily notice any commotion on the surface of the water. When faced with these conditions, it may be time to abandon your one-size-fits-all strategy and optimize your rig.

Optimizing your rigging for low and clear conditions entails downsizing your bobber, tippet, weight, and possibly even your flies. Trade in your one-inch Thingamabobber for a five-eighths-inch Corky. Scale back to 4X or even 5X tippet. Use the bare minimum amount of lead to get your fly down near the bottom. Depending on your fly selection, you may not need any lead at all. A size 14 Copper John sinks well and will drag a second, smaller nymph down with it. Fish with this rig for a while and you will be amazed at how much less commotion it makes when you land it on the water. That softer presentation can make a huge difference when rivers are low and clear.

There are times when it doesn’t matter what terminal tackle you use — if the fly or weight or indicator or leader lands anywhere near a fish, the fish will spook. In this situation, long downstream drifts are the order of the day. If you’ve fished the Fall River, you will already be familiar with the long downstream drift. The basic idea is to land your fly well above the fish and feed out line to get a dead drift right over it. The main advantage of this technique is that all the commotion of landing your fly takes place well upstream. It also allows you to position yourself far enough from the fish to avoid spooking it by wading or boating too close.

It’s imperative to get a “clean” drift over the fish. A clean drift is one in which the indicator doesn’t twitch at all as you feed out your line. If your indicator jerks every time you try to play out more line, you might as well be watching football on your couch at home. If your bobber is twitching, your flies are twitching. Only a suicidal trout is going to eat flies that are doing the cha-cha on their way downstream.

Another aspect of indicator fishing has major implications for low and clear wintertime conditions: the hook set. To hook a fish before it spits the fly out, the hook-set has to be fairly vigorous. There really isn’t a stealthy way to properly set the hook. When we strike, it causes a lot of commotion on the surface of the water. The bigger your rig, the bigger the commotion. With a heavy fly line and a big bobber, sometimes an aggressive hook set results in a veritable explosion on the surface of the water. Even after downsizing the rig, a proper hook set makes a splash that can spook fish.

Since the commotion of setting the hook is unavoidable, the best thing you can do in clear, calm water is err on the shallow side with your rigging. It’s much better to get a few good drifts through each spot instead of snagging the bottom on your first drift. Hooking the bottom involves a lot of commotion, from the hookset itself to possibly having to retrieve your fly. Start off with a short drop (the distance between the indicator and the fly) and make some drifts. Gradually lengthen the drop until you start ticking bottom. By starting on the shallow side, you have a much better chance of hooking a fish the first time you set the hook rather than hooking a rock on your first drift and spooking all the fish in the hole.

It’s All about the Baetis

There is an axiom for tough summertime trout fishing: heat shrinks. That is, when the fishing gets tough in the dog days of summer, fish with smaller flies than normal. Well, it turns out that cold also shrinks. There aren’t many aquatic insects that hatch during the winter months. On many rivers, the only bugs hatching on a clear and cold day are likely to be midges and Baetis mayflies. The midges are frequently the size of flying dust, and the mayflies are usually size 18 to 22.

The Baetis mayflies, also called BlueWinged Olives or BWOs, can be imitated by a wide variety of commercially available nymph patterns, many of them patterns invented by California tyers, including Mike Mercer’s Micro Mayfly, Hogan Brown’s S&M Nymph, and David Sloan’s Mighty Mite. I also like the WD-40, Pheasant Tail Nymph, Idylwilde’s Tailwater Tiny, and Ken Morrish’s Anato-May. Some of these commercial patterns are available as small as size 18 and others go all the way to a size 20. These Baetis nymph imitations can be fished on light tippet (5X or 6X) under an indicator.

Winter days can also bring excellent opportunities to catch trout on Baetis dries. There are many different imitations that work, but my favorite is a Parachute Adams in size 18 to 22. Tie these to a 9-foot leader tapered to a 6X tippet. Search the bubble lanes, tailouts, and shallow riffles for rising fish. The best time to find rising fish is in the afternoon. Baetis nymphs are available to the trout all day, but the trout typically don’t start actively feeding on them until the nymphs begin to emerge around midday.

I think most anglers, during their formative years, have heard from their fishing mentor that the best times to catch trout are dawn and dusk. Well, Grandpa was right, but what is lost on most of us is that he was talking about summertime trout fishing. I guarantee you that Grandpa wasn’t on the water at his favorite trout stream at 6:00 A.M. in February. Maybe he got an early start when steelheading, but that’s a whole different story. Here’s a better year-round approach to determining when to fish: the fishing will be best at the time of day when you’re comfortable wearing a T-shirt outside. In the summer, that means early and late. In the winter, that means the afternoon hours. So sleep in, read the paper, split some wood, have some coffee. Have a big breakfast. Get out there around 11 A.M., and you’ll only be about an hour too early. During cold weather, all of the bug activity for the whole day is usually compressed into a short window, and the hatch can be pretty intense. The fish suddenly become active and move into areas where they can feed on the emerging nymphs and duns. Areas that you fished through at A.M. without a bump are now filled with actively feeding trout. Make the most of it; the action may be done by 3:30 P.M.

Since the Baetis hatch will provide action only in the early afternoon hours, it’s good to have a strategy for the early and late parts of the day — other than sleeping in, that is. One good thing about the lack of a hatch is that fish are not likely to be too selective in the morning or evening hours. Try basic attractor nymphs, such as Princes, Hare’s Ears, and Copper Johns in sizes 10 to 14. If you are on a stream with large stoneflies, try a big rubberlegs nymph. These large stoneflies have a three-year life cycle, so the fish are looking for them year-round. Another good bet during the winter months is an egg pattern. Brown trout spawn in the early winter, and rainbows spawn in the late winter and early spring. If you’re on a valley river with salmon present, eggs will definitely be on the trouts’ radar.

Low, Clear, and Cold on the Steelhead River

Any steelheader knows that prime time is when the river is dropping and clearing. Steelhead are on the move during the high flows. Then, as the river drops and clears, they settle into new holes and are relatively eager to eat flies. But after a couple of weeks with no rain, fishing is much more challenging. Clear water makes the fish hard to approach without spooking them. The fish have seen some flies and may have even been caught, so they’re more careful. They’ve been in the same spot for a couple of weeks and are behaving more like fussy spring creek trout than steelhead. Add some cold weather to this scenario, and the fish aren’t likely to move very far to eat your fly, even when they’re in the mood.

If you’re indicator nymphing for steelhead, a lot of the advice mentioned earlier about nymphing for trout will help. I also encourage you to make the attempt to sight fish. In other words, try to spot a fish and then try and catch it. Low and clear water is ideal for spotting steelhead. If there’s a two-foot-long fish around, and you can get a good vantage point (often from a road or bridge), odds are that you can see it. Then craft a plan for drifting a nymph really close to the fish.

Whether you are nymphing or swinging flies for steelhead, downsizing your fly can really help in low and clear water. If you like to fish nymphs for steelhead, swap your size 12 Copper John for a size 16. If you can’t imagine a two-foot-long anadromous fish eating a size 16 nymph, just try fishing one and see what happens. I don’t get it either, but it works. I’d much rather hook steelhead on a larger hook, but when the water is low and clear, sometimes the fish will eat only small nymphs.

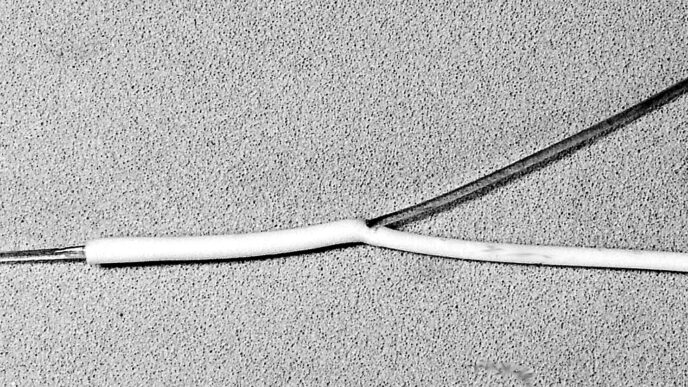

Downsizing the fly also works well for traditional and Spey patterns. My goto rig for steelhead is a four-inch Articulated Egg-Sucking Leech. But when the river gets low and clear, I have more success with smaller versions of the Black Leech. Small conehead tube flies with a minimal amount of dressing also work very well in low water. I like to tie them just about an inch and a half in length.

Many coastal rivers have closures in the winter when flows fall below certain levels, so be sure to check your regulations before heading out.

Clear and Cold on Still Waters

There is a lot of great fishing to be had on California still waters during the winter months. The first thing to look for when the water is clear and the weather is cold is any evidence of a midge hatch. Look for midges swarming on the surface. Watch for sneaky rise forms in the surface film. The best midge hatches are typically in shallow lakes with plenty of weed growth. Midges on still waters are typically size 20 or smaller. Fortunately, adult midges that are incredibly small will occasionally clump up into midge clusters that can be imitated with small dry flies.

Midge pupae can be imitated with small nymph patterns such as the Zebra Midge, Disco Midge, Brassie, and WD-40 in sizes 18 to 22. Fish these under an indicator, under a dry fly, or on a greased leader. The greased-leader approach involves smearing fly floatant on your leader to within a few inches of the fly. This will put the midge pupa right below the surface, and you should see a bulge on the surface if the fish deigns to eat your fly.

When fish are feeding on adult midges, try a Parachute Adams or Griffith’s Gnat, size 20 to 24, on a long 6X or 7X leader.

If you can’t see any midge activity, it’s highly likely that there really is not much on which the fish can feed. This is a good thing! If there is little in the way of regular feeding opportunities, trout are typically hungry and on the prowl for just about anything that moves. In this case, a big Woolly Bug-ger or Matuka streamer will often work very well. Troll it behind your float tube, cast it toward the bank, or cast to drop-offs and other structure. Cover lots of water, and you’re likely to find a hungry fish.

The challenge of clear and cold conditions on still waters is magnified by the lack of wind or wave action. A glassy smooth surface makes presenting your fly without spooking fish nearly impossible. In all likelihood, fish will spook away from even the most delicately presented cast. In these circumstances, your best bet is to make a long cast and let your fly sit long enough for the fish to come back after spooking. It could be several minutes before the fish come back to the area where your fly landed. This wait-’em-out technique works best with dries, dry/dropper, and indicator rigs. Any sinking line will usually sink to the bottom in less than a minute. In a shallow lake, you can also fish a nymph on a floating line with a long leader. The nymph will hang down while you’re waiting and will gradually rise up when you finally start your retrieve. Leave it out there for a good two or three minutes before starting your retrieve.