Editor’s note: I lived for a number of years in San Francisco, and, when not fishing, one of my favorite recreations then was to walk. On weekends I would sometimes walk for hours, and often my perambulations would involve visits to used-book stores, in search of fly-fishing titles. One day, in a disorganized, musty shop in Noe Valley, I came across a few slender copies of a publication called California Fish and Game that had been published by the Division of Fish and Game of the California Department of Natural Resources. These particular copies dated from 1929, and their articles dealt mostly with the research of the day and activities of the division. As I riffled through the pages, however, one of the articles caught my eye. Titled “Trout Fishing in California Today and Fifty Years Ago,” it described angling as experienced in the northern part of the state not just back in 1929, but in the latter half of the 19th century, with a focus on the San Francisco Bay Area. It is reprinted here to highlight the role of angling regulations in protecting gamefish populations, and also to help us understand how very much we have lost over the decades.

It is said that “angling differs from fishing in that it is practiced not as a means of obtaining a livelihood but a source of recreation and refining pleasure. It implies a certain degree of aesthetic culture, coupled with moral and religious susceptibility, and is thus preeminently the scholarly gentleman’s pastime — the brainworker’s diversion.

“The meditative, humane, unselfish nature of the angler is proverbial, [as is] his sympathetic disposition, his regard for the rights of others, his moderation in the pursuit of his sport. Angling may, therefore, be appropriately defined as a ‘school of virtues,’ in which, while the tendency to introspection and self-examination is decided, men learn also the lessons of wisdom, resignation, forbearance, and love — love for the lower forms of animal life, love for their fellow creatures, and love for the God of Nature.”

That is why when

“Nature calls and we long to go

Into the woods where the sweet pines grow;

Where the swift brook runs and the big trout play —

O’er the hills and far away.”

Since at this time so much is being said and done regarding the depletion and restocking of trout streams and public waters of the state, it occurs to me that a review of the causes largely responsible for present conditions will offer a moral and discourage their repetition so that future generations may enjoy the sport of fishing for trout, and may practice the “art of angling” in California.

It was long and faithfully believed by observing fishermen that all of the trout, colloquially called “mountain trout,” “brook trout,” “rainbow trout,” “salmon trout,” and “silversides,” which inhabited the waters of the coastal streams of California, were steelhead trout. It is now known that steelhead belong to a particular group of fish anadromous in habits. Their connection with the sea is not an incident, but a potent element to the reproduction, growth, and development of the species, and these facts are now well established by scientific investigation.

Many present-day anglers listen with deep interest and great wonder to the stories dad and “old timers” tell of the great catches they have made and of the big ones that didn’t get away, during the good old days when the lakes, rivers, and streams of California teemed with trout, salmon, and other game and food fish. Reflecting on present conditions, and with a deep sigh, they wish that they, too, could enjoy such sport with rod and line.

In 1867 I caught my first trout in Alameda Creek, near Sunol, Alameda County. My first real catch of trout was taken from San Gregorio Creek, San Mateo County, in 1869, and for thirty-five years thereafter I annually fished the streams of this and Santa Cruz County, as well as many other streams within the state.

During all of these years the catching of steelhead trout was not confined to hook and line. Night fishing and the sale of trout was not prohibited. The season opened above tidewater on April 1, but one could legally catch trout in tidewater during the entire year. It was not until about 1905 that a creel limit was placed upon the daily catch of trout.

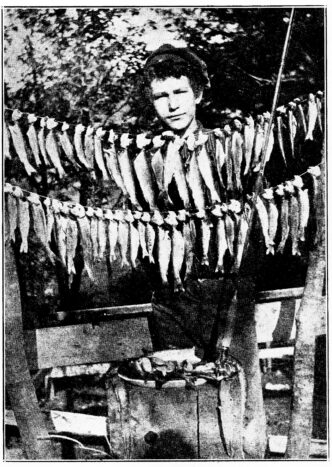

Prior to 1905 and the enactment of a law fixing the daily creel limit at 50 trout, a catch of from 100 to 300 trout taken from the coastal streams by one fisherman during the day was not unusual. A catch of a dozen adult steelhead trout, or from 20 to 30 so-called “grilse” (one and two-pound steelhead trout) was not exceptional. I can personally vouch for, since I have seen catches of this kind made in the San Gregorio, Pescadero, Butano, Waddell, Scotts, San Lorenzo, Soquel, and Aptos creeks in San Mateo and Santa Cruz counties, to say nothing of the catches of steelhead trout that were made in Paper Mill Creek, the Russian, Gualala, Garcia, Eel, Klamath, and other coast rivers and streams.

Between 1895 and 1905 fishermen who sold their fish frequently made catches of from 200 to 350 trout per day in the streams of Santa Cruz County. These fish were sold at Santa Cruz at an average price of about 1 cent apiece, the average price paid for adult steelhead trout being about ten cents per pound.

In April, 1900, I saw 600 (four to ten inches) steelhead trout that had been taken on hook and line from Soquel Creek in Santa Cruz County, by one fisherman during one day. I have seen as many as 27 adult steelhead trout speared by one fisherman in Butano Creek, near Pescadero, during one night. I recall a catch of 618 trout and 21 adult steelhead trout taken on book and line by four fishermen during one day in the lagoon at the month of San Gregorio Creek, in April, 1887.

During the sixties, seventies, and eighties, thousands of so-called “grilse” or “salmon trout” were caught by hook and line by fishermen fishing off “Meiggs Wharf,” from the wharves all along the San Francisco waterfront, and off the Oakland Mole. On any Sunday during the fall months of these years hundreds of fishermen could be seen all along the wharves of San Francisco Bay and the Oakland Mole fishing for steelhead trout. The rig used by these fishermen was similar to that used by smelt fishermen, being a bamboo cane pole, corn float, and hooks baited with mussel, pile or angle worms, and fresh shrimps.

During the seventies and eighties I was able to take many a creel of nice trout from San Mateo, San Francisquito, Adobe, Stevens, Los Gatos, and other streams in the Santa Clara Valley. Among the fishermen who fished for steelhead trout in the streams of the Peninsula and along the coast within 100 miles of San Francisco from the sixties to the nineties were Alex and James Butchart, Al Weeks, Al Goldson, Harry and Ed Thompson, “Stor” Armas, Dave Mills, P. P. Chamberlin, Lon Cook, Charley Green, Tom McLachlan, John Benn, John Butler, Al Wilson, J. P. Babcock, M. L. Cross, Ed Jenney, Harry Green, Ted and Bert Blanchard, “Bootsie” Griffiths, and many others. While the majority of these fishermen found their sport in fishing for adult steelhead in the lagoons at the mouths of the streams, Ed Jenney, Harry Green, Ted and Bert Blanchard, and “Bootsie” Griffiths fished the streams of Santa Cruz County. Their outfit consisted of a light cane pole, a spool of linen tread which they used as a line, and a few snell hooks, sizes 7 to 9. With a few BB shot to be used as sinkers, and using sand fleas and angle worms for bait, they were able to exceed the catches, in both large and small trout, made in the streams by other fishermen.

While I have not had as much experience in fishing for rainbow and other trout native to the lakes and streams of the Sierra as I have had in fishing for steelhead trout along the coast, I have witnessed the depletion of trout in those lakes and streams. For years I had heard that the fishing for rainbow trout to be had in the Truckee River was not to be equaled in any part of the world, and that Lake Tahoe, Donner, Webber, and Independence lakes teemed with trout of great size, but it was not until about 1902 that I was able to wet a line in those waters. In May of that year I went to Independence Lake, where I saw four fishermen take on hook and line, and in a lawful manner, an average of 50 pounds of trout each per day. For several years these four men had made it a practice to go to Independence Lake each year during the months of April, May, and June. Their daily average catch was 50 pounds of trout each, the trout being shipped from Corey’s Station to Truckee, where they were sold for 27-1/2 cents per pound.

For several years prior to the passage of the law which limited the daily catch of trout to 50 trout not to exceed 25 pounds in weight, not pounds but tons of trout were taken from Independence Lake during the months of April, May, and June of each year, and were shipped and sold on the open market.

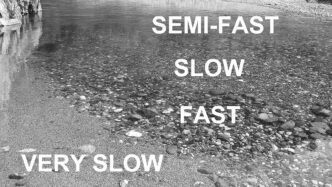

The conditions relative to market fishing for trout that prevailed at Independence Lake during these years also prevailed at lakes Webber, Donner, and Tahoe, and all along the Truckee River. I recall having stood on the banks of Blackwood Creek about 11 o’clock A.M. on a day in June, 1904, and in twenty minutes having counted no less than thirty adult trout pass a given point in that stream on their way upstream to their spawning beds. On the same day there were about twenty market fishermen in boats fishing for trout in Lake Tahoe off the mouths of Blackwood, Ward, McKinney, and other streams that flow into the lake.

It is safe to say that during a number of years before the law prohibiting the sale of trout in this state was passed, from one to two thousand pounds of trout taken from these lakes and the Truckee River were shipped daily and sold in the markets of San Francisco and other cities. The result was that the accessible lakes and streams of the Sierra, as well as those along the coast, were overfished and depleted of their once bountiful supply of native trout. During the years mentioned anglers were known as “fishermen” and their rod and fishing outfit was referred to as “pole and rig.” The reputation of being a fisherman was based on the number of fish one was able to catch, irrespective of size, how, when, or where the fish were caught. The great majority, if not all, of the native trout caught during the months of April, May, and June, and speared during the winter months, were either in a spawn-bearing, breeding, or spent condition. What spring shooting did to our ducks and geese, this spring fishing did to our trout.

During the years of wholesale and oftentimes wanton fishing, those who angled with split bamboo rods, light tackle and flyhooks were stigmatized as “sports.” They were seldom to be seen on the streams in the spring months, and when they did put in an appearance were more or less sneered at.

It is needless to say that had there been more “anglers” or so-called “sports” and less “fishermen” during the early days, there would be more trout in the lakes and streams of the state today. The great majority of the old-time “fishermen” with pole, rig, and spear have passed on and crossed the Great Divide. The “angler” with split bamboo rod, light tackle and flyhooks has now taken his place along the lakes and streams.

I am wondering if the anglers of today will be more considerate than the fishermen of yesteryear? I am wondering if the anglers of today will practice their art as a “source of recreation and refining pleasure,” or will they be “fishermen” and continue the slaughter of spawn bearing, breeding, and spent trout during the spring months? I am wondering if the anglers of today

“With rod and creel will wander away And cast a fly where the rainbows stay; To feel the thrill when the game fish rise And strike at the coachman flies.” or be “fishermen,” and, using salmon eggs for bait, continue to creel fingerling trout irrespective of size.

Regardless of what the Division of Fish and Game may do towards restocking the streams and depleted waters, upon the answer to the above question rests the future supply of trout and the angler’s opportunity to practice the art of angling in California.

Reprinted from California Fish and Game, January, 1929; volume 15, number 1; published in Sacramento, California.